Where Completed Drains Get Funded, Marikina Floods, and Anti-Corruption Vows Are Just Hot Air

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — September 2, 2025

Opening Salvo: A Budget That Mocks Marikina’s Misery

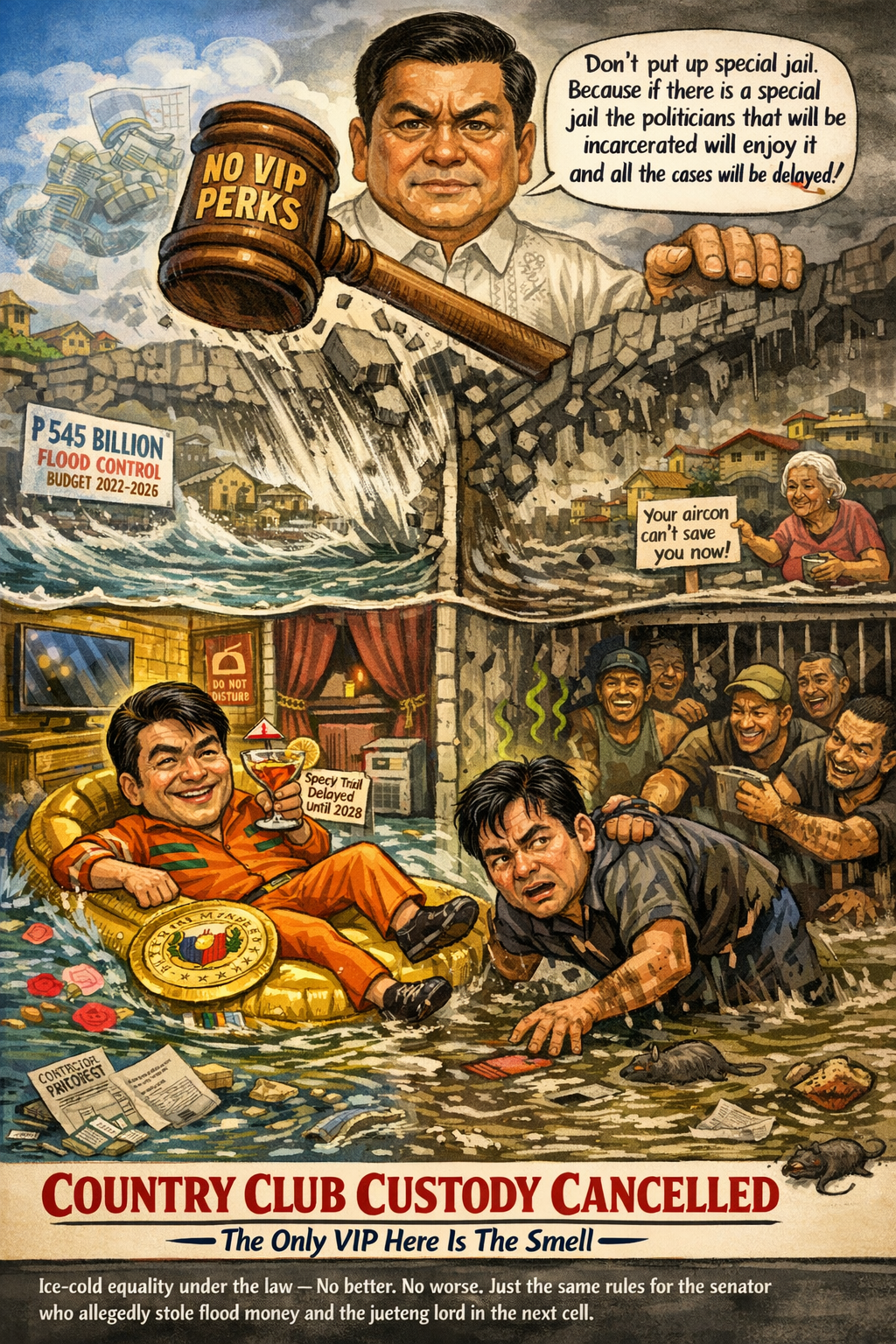

Picture this: the 2026 National Expenditure Program (NEP), a bloated tome of fiscal fantasy that makes the PDAF scandal look like a petty cash mix-up. While Marikina’s residents wade through floodwaters, the Department of Budget and Management (DBM) and Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) have crafted a budget that funds already-built flood-control projects, pristine roads, and cryptic “drainage outfall phase one” schemes. It’s a tragicomedy of graft and incompetence, a bureaucratic middle finger to a nation drowning in both water and broken promises. Welcome to the Philippines, where anti-corruption rhetoric is a lullaby, and the budget is a love letter to chaos.

The Grand Hypocrisy: Anti-Corruption Lip Service Meets Old-School Shenanigans

The Philippines loves to strut its anti-corruption credentials. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crimes (UNODC) once cheered our “progress,” and the shiny new Public Financial Management Roadmap promises a fiscal utopia. Yet, the 2026 National Expenditure Program (NEP) is a slapstick sequel to every corruption scandal we swore to bury. Rep. Marcelino Teodoro’s exposé—revealing funds for completed Balanti Creek slope protection, unblemished Malaya Street, and a half-funded Sumulong Highway drainage—exposes the rot beneath the reformist veneer. This isn’t a budget; it’s a performance piece, mocking the very transparency we claim to champion. The irony is thicker than Metro Manila’s floodwaters: we preach anti-corruption while our flagship agencies churn out line items that reek of pork barrel’s ghost. Is this progress, or just the same old scam with a better PowerPoint?

Legal Bloodbath: Slicing Through Budgetary Bull with Constitutional Knives

Let’s wield the Constitution like a machete. Article VI, Section 25(1) demands itemized appropriations, a principle the Supreme Court in Belgica v. Ochoa (2013) used to gut the lump-sum abomination of PDAF. Yet, the NEP’s “drainage outfall phase one” entries—lacking location, scope, or sense—laugh in the face of this mandate. Are these the new PDAF, cloaked in infrastructure jargon? DBM and DPWH seem to think “itemization” means scribbling riddles that could fund a culvert or a congressman’s vacation villa. The President’s line-item veto, meant to curb such nonsense, is neutered when budgets read like abstract haikus.

Then there’s RA 3019, Section 3(e), the Anti-Graft Act’s guillotine. Funding finished projects like Balanti Creek or pristine roads like Malaya Street screams “gross inexcusable negligence” at best, “evident bad faith” at worst. These aren’t typos; they’re unwarranted windfalls for contractors giggling their way to the bank, while Marikina’s flood victims suffer “undue injury.” Every misallocated peso is a statutory betrayal. And don’t sleep on Revised Penal Code (RPC) Article 220 (technical malversation). Vague line items are a blank check, ripe for diversion to a yacht or a “consultant’s” offshore account. If these funds are realigned without statutory blessing, as Araullo v. Aquino (2014) forbids, we’re not talking incompetence—we’re talking crime.

DPWH’s “shock” at these revelations is a pathetic charade. Their own Department Orders on blacklisting contractors and anti-graft committees gather dust while regional directors play clueless. Did the left hand ghost the right? Or is “shock” just code for “caught”? Failing to cross-check project lists against MMDA’s recent works or their own completion reports suggests a system built to fail—or to funnel. It’s a flagrant violation of RA 6713’s call for professionalism and public interest, a standard so basic it’s insulting they can’t meet it.

Whistleblower or Showman? Teodoro’s Crusade Under the Microscope

Rep. Marcelino Teodoro steps into the spotlight as the whistleblower of the hour, bravely exposing the NEP’s absurdities. His push to return the budget to DBM and his tag-team with Deputy Speaker Ronaldo Puno earn a slow clap for aligning with RA 6713’s public interest mandate. But hold the halos. Teodoro’s a politician, not a martyr, and his sudden eagle-eyed vigilance smells like political theater. Why catch these glaring duplications now, when they’re as subtle as a monsoon? Is he genuinely incensed, or is this a pre-election glow-up as an anti-corruption crusader? The Ombudsman’s whistleblowing rules highlight the government’s dirty secret: vigilance is a rarity, not the norm. If a congressman has to play Sherlock on budget bloat, where’s the systemic oversight? Why aren’t DBM’s number-crunchers or DPWH’s engineers spotting this before it hits the House? Teodoro’s act is laudable, but it’s a searing indictment of a system where whistleblowers are our only firewall.

Systemic Fallout: Torching the Rule of Law in a Flood of Funds

This isn’t just a budget blunder; it’s a funeral for the rule of law. The Constitution’s fiscal guardrails—itemization, line-item veto, public-purpose spending—are reduced to punchlines when budgets fund phantoms. Belgica and Araullo were supposed to end this circus, yet vague appropriations invite post-award sleight-of-hand. The Supreme Court’s Madera v. COA (2020) demands refunds from those who pocket disallowed funds, but why are low-level clerks sweating while department secretaries greenlight billion-peso budgets with a yawn?

The 2018 PFM Roadmap’s anti-corruption vows aimed to streamline accountability, yet the real culprits—department secretaries approving ghost budgets—seem bulletproof, unlike low-level clerks under the Madera doctrine. Public trust drowns when floodwaters rise but funds flow to finished drains. With corruption siphoning 20% of the budget annually, this isn’t inefficiency—it’s a betrayal of the social contract, leaving Marikina’s residents to swim in the wreckage.

Savage Solutions: Fixing a Fiscal Fiasco with Fire and Brimstone

To slay this beast, start by enrolling DBM and DPWH officials in a remedial crash course on the Administrative Code (PD 1445). If “public funds for public purposes” is too complex, maybe a pop-up book will help.

Next, erect a national shrine to stupidity: “The Memorial to the Completed But Still Funded Drainage Ditch,” a taxpayer-funded testament to their genius. DPWH’s new Anti-Graft Committee should launch by raiding its own offices—start with the coffee machine.

Pass a whistleblower protection law that actually works, because the current system guards insiders like a tissue in a typhoon. Mandate GIS-tagged project sheets, cross-checked against a public registry of completed works, before a cent leaves the Treasury.

If DBM can’t filter out “drainage outfall phase one” gibberish, swap their analysts for a spreadsheet. And Congress? Slap a GAA rider: no funds without geospatial specs and cost breakdowns online.

Anything less is an open invitation to rob the public blind.

Final Nail: A Budget That Begs for the FATF Grey List

As the Philippines gears up for its 2026 Financial Action Task Force (FATF) review, hoping to escape the grey list’s shame, this budget is a self-inflicted gunshot. How do we sell financial integrity when our NEP reads like a heist novel? Funding completed projects, vague line items, and half-baked drainage plans aren’t errors—they’re a billboard screaming “corruption as usual.” DBM and DPWH have turned the budget into a work of fiction, and Marikina’s flood victims pay the price. If we can’t scrub our fiscal house clean, the FATF will keep us in the doghouse, and the only thing we’ll drain is the nation’s credibility. Fix it, or sink.

Key Citations

- Inquirer Report on Teodoro’s Allegations: 2026 Budget Allots Funds for Already Finished Flood-Control Projects

- Wikipedia: Pork barrel scam

- Belgica v. Ochoa (G.R. No. 208566, November 19, 2013): Supreme Court ruling on PDAF’s unconstitutionality.

- Araullo v. Aquino (G.R. No. 209287, July 1, 2014): Supreme Court ruling on DAP and unauthorized fund transfers

- Madera v. COA (G.R. No. 244128, September 08, 2020): Supreme Court ruling on refund liability for disallowed funds.

- RA 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act): Legal framework for graft offenses.

- RA 6713 (Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards): Norms for public officials.

- PD 1445 (Government Auditing Code): Rules on public fund use.

- RA 9184 (Government Procurement Reform Act): Procurement regulations.

- RPC Article 220 (Technical Malversation): Penal code on fund diversion.

- DPWH Department Orders:

- DPWH Department Order No. 28, series of 2024 (PDF) – DO specifying contractor blacklisting policies.

- DPWH Department Order No. 166, Series of 2025 – DO creating the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Committee.

- Ombudsman Whistleblowing Rules: Framework for internal reporting.

- FATF Grey List Review: Philippines’ status and upcoming evaluation.

- Corruption Cost Estimate: 20% of budget lost to corruption.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment