How one family turned infrastructure into inheritance, mocking the Constitution’s anti-dynasty dreams.

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — September 4, 2025

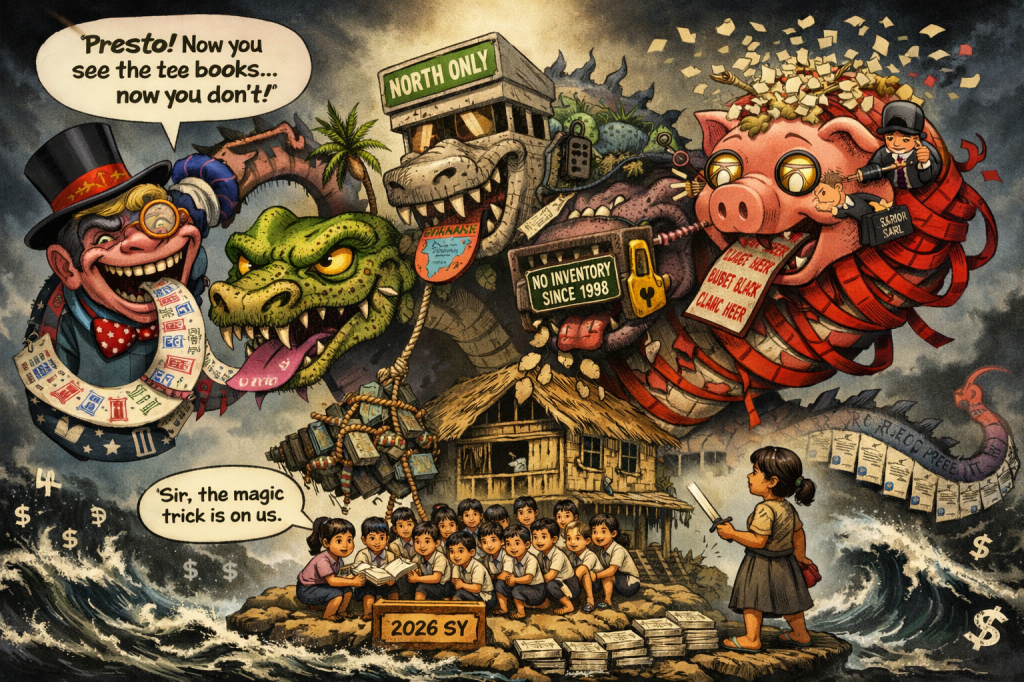

IN THE Philippines, rivers may run deep—but nowhere near as deep as the pockets of its political families. The Aurelio “Dong” Gonzales Jr. flood control scandal isn’t just another infrastructure flop; it’s a masterclass in dynastic entitlement that even Machiavelli would envy. Amid legal twists and turns, this P913 million saga, masked behind A.D. Gonzales Jr. Construction and Trading Company, exposes a brazen family plunder. Armed with razor-sharp sarcasm and backed by Supreme Court rulings and an explosive Rappler exposé, we’re about to unravel the layers of this audacious “public service” farce. Hold tight—it’s going to be a bumpy ride through a corrupt swamp.

1. The Family Fiefdom: A Corporate Con Named After Daddy

Let’s marvel at the ingenuity of A.D. Gonzales Jr. Construction, a corporate entity so blatantly branded it might as well have “Dong’s Dynasty LLC” on the letterhead. Incorporated in 1993 with Aurelio “Dong” Gonzales Jr.—civil engineer turned five-term congressman—as an original incorporator, this family firm hit the jackpot between 2023 and 2024, bagging P913 million in DPWH flood control contracts in Dong’s Pampanga 3rd District (San Fernando City, Bacolor, Mexico). The ownership? A cozy 98% split among his kids: Aurelio Brenz P. Gonzales (60%, president, ex-councilor, now vice mayor), Aurelio M. Gonzales III (19%, vice president), and Aurelio Michaeline M. Gonzales (19%, secretary-treasurer, now deputy majority leader succeeding Dad in Congress). With a triple-A license from the Philippine Contractors Accreditation Board (PCAB) and P239 million in assets, it’s a dynastic cash cow masquerading as a contractor.

Prima facie, this begs for piercing the corporate veil under the Corporation Code (RA 11232). The Supreme Court in McLeod v. NLRC (G.R. No. 146667, January 23, 2007) shredded the corporate fiction when used as a shield for fraud or injustice. Here, the firm’s name, Dong’s engineering chops, and the suspiciously localized P913 million in contracts scream “alter ego” louder than a barangay karaoke night. The setup—Dong as deputy speaker with budget clout, kids running the firm, projects in his exact district—is less a corporation and more a family piggy bank plugged into public funds.

And the “divestment”? A legal fiction so flimsy it’s practically tissue paper. RA 6713, Section 9 mandates divestment of conflicting interests within 60 days, explicitly not to first-degree relatives like Dong’s kids. The Implementing Rules of RA6713 (Rule IX, Section 2(c)) double down, banning such transfers to dodge conflicts. Yet, the 2024 SEC General Information Sheet shows the kids holding 98%, a move budget expert Cielo Magno called out as a sham in Rappler’s probe. The Supreme Court in Presidential Anti-Graft Commission and the Office of the President v. Salvador A. Pleyto (G.R. No. 176058, March 23, 2011) flagged family benefits from official influence as a conflict. This isn’t divestment—it’s dynastic sleight-of-hand, a middle finger to Article XI, Section 1 of the Constitution‘s public trust doctrine.

2. A Smorgasbord of Sins: Legal Liabilities Galore

The Gonzales clan’s banquet of potential violations is a feast for prosecutors. Let’s carve it up:

Dong Gonzales:

RA 3019, Section 3(h) bans public officials from having “directly or indirectly any financial or pecuniary interest” in government contracts they influence. As deputy speaker, Dong’s budget advocacy funneled DPWH funds to his district, enriching his kids’ firm—an indirect interest if ever there was one. Add Article 216 of the Revised Penal Code (prohibited interest in contracts), punishable by up to 2 years and 4 months in jail for indirect stakes. As co-conspirator under RA 3019’s penalty clause (Section 9), his role in budget insertions ties him to the grift. Villarosa v. People (G.R. Nos. 233155-63, 2020) demands bad faith, but P913 million in family contracts screams it.

The Progeny (Brenz, et al.):

Brenz, a San Fernando councilor during the 2023 awards, faces RA 3019, Section 3(a) for potentially inducing DPWH officials to favor the family firm, or Section 3(k) for relatives contracting with influenced agencies. Michaeline and the third son, while not public officials then, could be accessories under RPC conspiracy if they leveraged Dad’s clout. Their SEC filings, showing unified family control, don’t help their case.

DPWH Enablers:

Central Luzon officials who greenlit these bids risk RA 3019, Section 3(e)—giving “unwarranted benefits” through “manifest partiality.” Awarding P913 million to a firm named after the local kingpin, in his exact turf, without rigorous scrutiny? That’s partiality on steroids. Rodrigo Deriquito Villanueva v. People (G.R. No. 218652, February 23, 2022) convicted for procurement irregularities implying graft. Under RA 9184 (Procurement Law), bids must be clean, but this smells like a rigged raffle.

3. The Ombudsman’s Kabuki: Dismissal, Refiling, and Res Judicata Ruses

The Ombudsman’s December 2024 dismissal of barangay captain Terence Napao’s graft complaint—alleging RA 3019 and RPC Article 216 violations on three projects—is a masterclass in bureaucratic ballet. “Baseless,” Dong crowed in a SunStar piece, conveniently post-election as his daughter ascended to Congress and son to vice mayor. The timing? Suspiciously cozy for a Romualdez ally. The rationale? Opaque, hinting at a whitewash to protect the powerful.

Napao’s planned September 2025 refiling, per Rappler, hinges on new evidence—perhaps SEC filings or budget insertion records. RA 6770, Section 12 allows reinvestigation for probable cause, and Ombudsman Administrative Order No. 07, Rule II, Section 7 permits refiling if dismissal was without prejudice or with fresh proof (People v. Sandiganbayan, G.R. No. 164577, 2006). Res judicata? A non-starter—administrative dismissals lack judicial finality (Vergara v. Ombudsman, G.R. No. 174567, 2009). Napao could also certiorari the dismissal via Rule 65, but refiling with evidence of Dong’s influence (e.g., deputy speaker budget clout) keeps the case alive. Yet, the Ombudsman’s track record suggests a slow fade to obscurity—less justice, more kabuki.

4. From Whitewash to Cellblocks: The Gonzales Gambit’s Possible Fates

Best-Case (Dong’s Dream):

Ombudsman doubles down on dismissal, waving off refiling as harassment. Dichaves v. Ombudsman (G.R. Nos. 206310-11, December 7, 2016) shields such moves absent grave abuse. Outcome? A trapo triumph, shredding trust in RA 3019 and emboldening dynasties. Voters shrug, and Dong basks in impunity.

Worst-Case (Dynasty’s Nightmare):

Sandiganbayan finds probable cause, launching a trial epic. Picture Dong and kids in the dock, budget manipulations exposed, à la Martel v. People (G.R. Nos. 224720-23, 2021), where DPWH officials were nailed for rigged bids. Penalties? Up to 15 years per RA 3019 count, perpetual disqualification, restitution up to P913 million, and RA 1379 forfeiture of ill-gotten wealth. Villanueva‘s (G..R. No. 237864, July 08, 2020) indirect interest precedent seals their fate—family benefits via Dong’s clout prove graft. Orange jumpsuits? A dynastic downfall for the ages.

Most Likely (Soul-Crushing Status Quo):

A plodding probe fizzles from “lack of evidence” or political pressure. Refiling drags to 2026, evidence vanishes, and prescription (10 years, RA 3019, Section 11) looms. The Gonzaleses—Mica in Congress, Brenz as veep, firm bidding anew—thrive, as the Ombudsman’s inertia buries justice. Depressing? It’s Philippine governance in a nutshell.

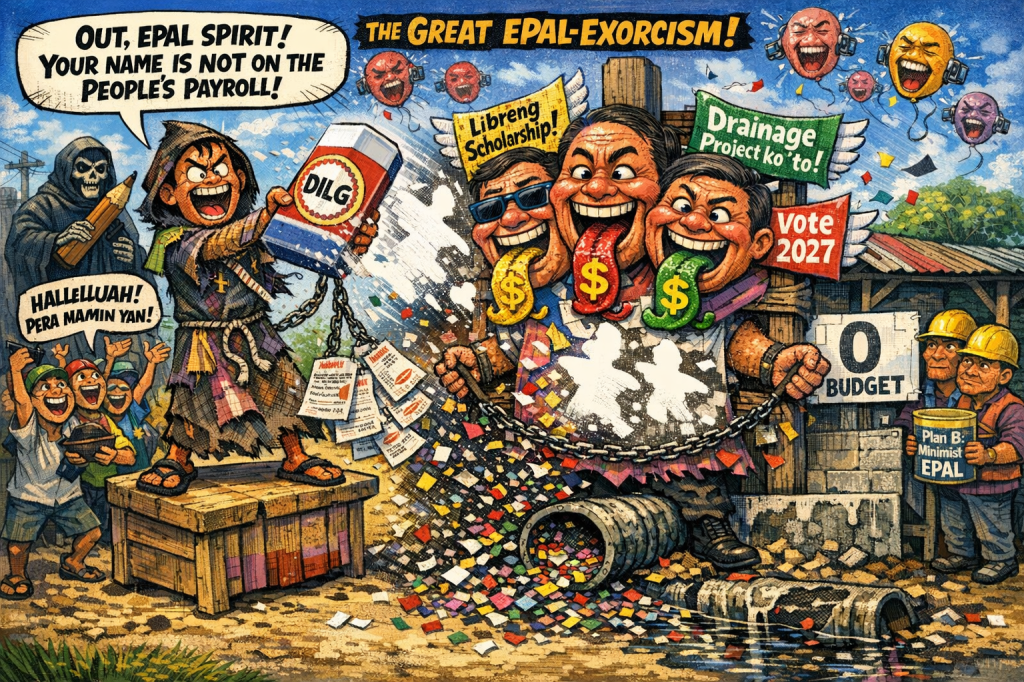

5. The Dynastic Disgrace: Legal Gaps and Scorched-Earth Fixes

This isn’t just a Gonzales problem; it’s a constitutional mockery. Article II, Section 26 demands banning political dynasties, yet Congress—stacked with dynasts like the Gonzaleses (Dad, daughter, son)—refuses an enabling law. Article XI, Section 1‘s “public trust” is a hollow hymn when RA 3019 and RA 6713 let kids inherit the grift. The legal gaps? Laughable. Why not just legislate the DPWH as the “Department of Dynastic Pork for Gonzaleses, Arroyos, and Pals”? Or require bid docs to sport family crests for honesty’s sake?

Real reform demands fire: Pass the anti-dynasty law, barring relatives from district contracts. Overhaul RA 9184 with mandatory third-party COA audits for congressionally linked bids—no more district-exclusive windfalls. Amend RA 6713 to criminalize family transfers, with veil-piercing as default in graft probes, per McLeod. Enforce RA 6770 timelines to curb Ombudsman dawdling, and impose perpetual bans for ethical breaches, even sans conviction. Protect whistleblowers like Napao with teeth, lest refilings die on the vine.

Final Judgment: A Republic Drowning in Dynastic Debris

The Gonzales saga isn’t a scandal—it’s a symptom of a republic rotting under dynastic weight. When a congressman’s kids pocket P913 million in public contracts, named after him, in his own district, and the Ombudsman yawns, it’s not just Pampanga’s rivers overflowing—it’s the public trust. Philippine governance is a tragic farce where trapos like Dong play the system like a cheap violin, leaving voters soaked and furious. Wake up,

Malacañang: enact the reforms, or the next deluge won’t just be water—it’ll be the rage of a nation tired of being played.

Kweba ni Barok

Key Citations

Statutes:

- RA 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act)

- RA 6713 (Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards)

- RA 6770 (Ombudsman Act)

- RA 9184 (Government Procurement Reform Act)

- RA 11232 (Revised Corporation Code)

- RA 1379 (Forfeiture Law)

- Revised Penal Code, Article 216

- 1987 Constitution, Article II, Section 26

- 1987 Constitution, Article XI, Section 1

Jurisprudence:

- McLeod v. NLRC (G.R. No. 125389, 1998)

- Presidential Anti-Graft Commission and the Office of the President v. Salvador A. Pleyto (G.R. No. 176058, March 23, 2011)

- Villarosa v. People (G.R. Nos. 233155-63, 2020)

- Martel v. People (G.R. Nos. 224720-23, 2021)

- Rodrigo Deriquito Villanueva v. People (G.R. No. 218652, February 23, 2022)

- People v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. No. 164577, 2006)

- Vergara v. Ombudsman (G.R. No. 174567, 2009)

- Dichaves v. Ombudsman (G.R. No. 193156, 2014)

- Martel v. People (G.R. Nos. 224720-23, 2021)

- Villanueva v. People (G..R. No. 237864, July 08, 2020)

Other Sources:

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment