Will Lipana’s Silence and Cordoba’s Caution Topple the Guardian of Public Funds?

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — September 14, 2025

The Opening Salvo: A Legal Thriller Unfolds

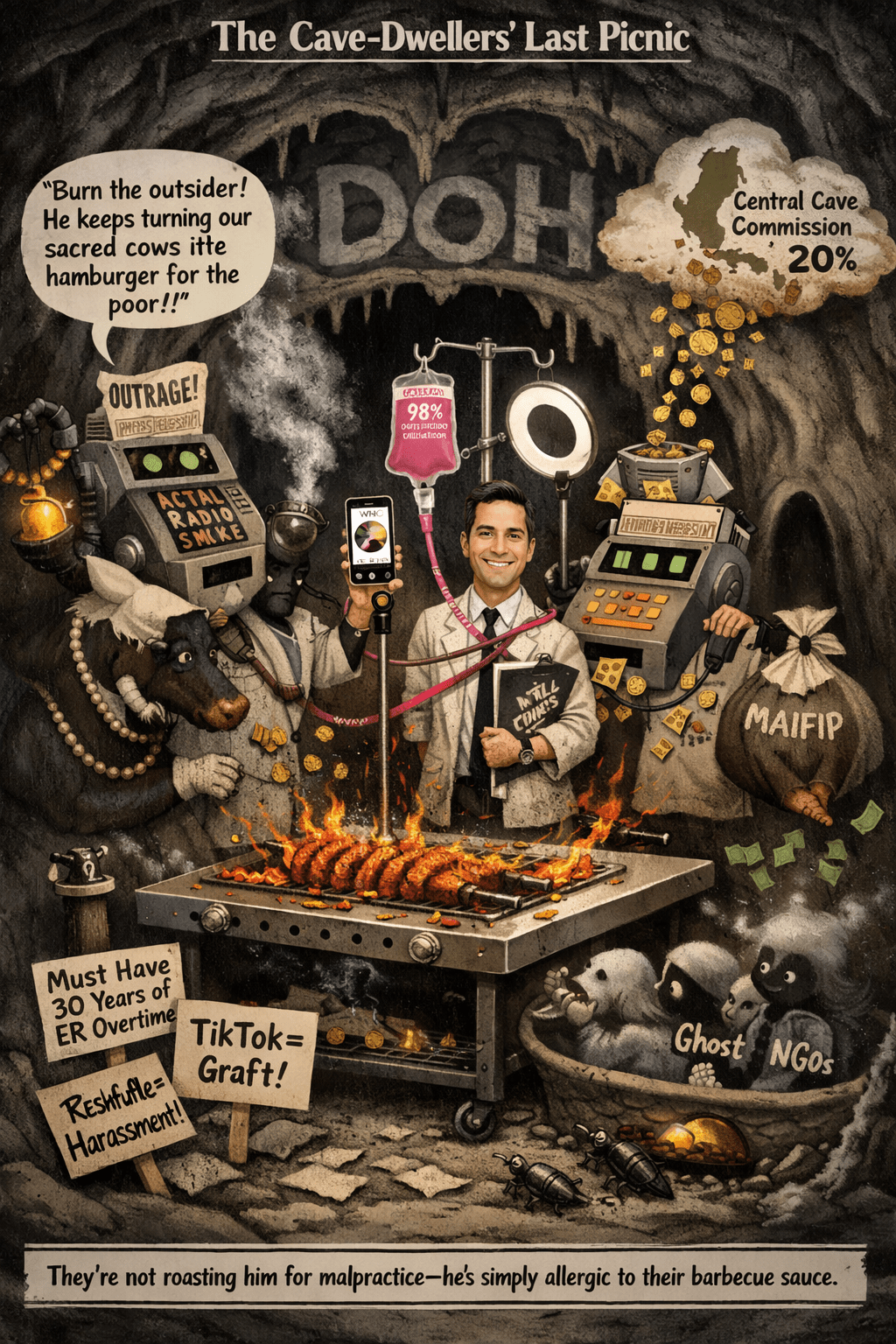

The hearing room crackles with electric tension, a legal battlefield where truth and power collide in a high-stakes duel. The Commission on Audit (COA), the constitutional guardian of public funds, is under siege. Chairperson Gamaliel Cordoba hurls a grenade: a “potential conflict of interest” involving Commissioner Mario Lipana, whose wife’s company, Olympus Mining and Builders Group, has reaped P326 million in government contracts from the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH).

The revelation hangs like a storm cloud, threatening to drown the COA’s sacred mandate in suspicion. Is this a mere bureaucratic misstep, a “potential” conflict to be swept under the rug? Or is it a full-blown constitutional crisis, a betrayal festering in plain sight, poised to shatter public trust? As lawmakers sharpen their rhetoric—some demanding resignation, others whispering impeachment—the question burns: will this scandal be buried in red tape, or will it ignite a firestorm that reshapes the republic?

The Players in the Dock: Heroes, Villains, or Pawns?

Commissioner Mario Lipana: The Silent Betrayer?

Imagine Mario Lipana, cloaked in the shadow of medical leave, his absence from the COA’s 2026 budget hearing louder than any defense. A master lawyer could build him a fortress. The 1987 Constitution, Article IX, Section 2, bars COA commissioners from any financial interest, direct or indirect, in government contracts. But Republic v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. No. 152154, 2003) demands hard proof of actual gain or control—where’s the paper trail showing Lipana pocketed a cent or swayed an audit?

The Family Code, Article 145, governing conjugal property, doesn’t automatically pin his wife’s profits on him without evidence of direct benefit. His due process rights, enshrined in the Administrative Code of 1987, Book V, Title I, Subtitle A, Chapter 5, shield him from mob justice. Notices of disallowance issued by other auditors suggest the COA’s machinery remains untainted. A deft defense could push recusal or divestment as remedies, not resignation, preserving his seat without admitting guilt.

But this fortress crumbles under the weight of scrutiny. The Constitution’s ban is a guillotine, slicing through nuance. Article IX, Section 2 doesn’t tolerate even indirect financial interest, and the Family Code, Article 91 binds Lipana to his wife’s P326 million windfall through conjugal property. The Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees (Republic Act No. 6713), Section 7(a), demands officials shun even the appearance of impropriety—Lipana’s continued tenure mocks this mandate.

The Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act (Republic Act No. 3019), Section 3(h), forbids pecuniary interests in transactions under an official’s purview; as a COA commissioner auditing DPWH projects, Lipana’s conflict screams betrayal. His silence, far from strategic, fuels outrage on social media platforms like X, where posts brand him a stain on the COA’s honor. The notices of disallowance, rather than clearing him, hint at irregularities his presence taints. Lipana teeters on a razor’s edge, his defense drowned by the Constitution’s unrelenting roar.

Chairperson Gamaliel Cordoba: Whistleblower or Weak Link?

Cordoba strides into the fray, a reluctant herald caught in a political maelstrom. His defenders cast him as a sentinel of transparency, duty-bound to flag a “potential conflict” in a public hearing. COA Resolution No. 2018-010 mandates integrity and independence, and Cordoba’s cautious “potential” phrasing aligns with due process under Rule 112 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure.

He lacks disciplinary power over a fellow commissioner, as Article XI, Section 2 of the Constitution reserves removal for impeachment, a point reinforced by Gonzales v. Office of the President (G.R. No. 196231, 2014). The auditors’ notices of disallowance bolster his claim that no tampering has been proven. Cordoba’s restraint is his armor, a calculated step to inform without convicting.

Yet his caution is a fatal flaw. Labeling a blatant constitutional breach “medyo meron” (somewhat a violation) is a spineless sidestep, a betrayal of RA 6713, Section 4(a)’s call for utmost responsibility. Public Interest Center, Inc. v. Elma (G.R. No. 138965, 2006) demands swift action to preserve constitutional commissions’ integrity—Cordoba’s hesitancy invites accusations of weakness or political calculation.

His failure to launch an immediate probe or refer the matter to the Office of the Ombudsman risks perceptions of complicity. X posts whisper of political ties, though unproven, amplifying the sense that Cordoba is playing a dangerous game of optics rather than wielding his authority to confront Lipana. His spark of transparency fizzles without the fire of decisive action.

The Gauntlet of Justice: Navigating a Minefield of Remedies

This scandal offers no easy escape, only perilous paths fraught with heroes, villains, and traps.

COA’s Internal Inquisition: Truth or Whitewash?

The COA could launch a fact-finding probe, as urged by Rep. Elijah San Fernando, to unearth procurement records, audit trails, and communications. COA Resolution No. 2018-010 empowers such inquiries, but the specter of a whitewash looms—commissioners are peers, and institutional loyalty could taint the process. The notices of disallowance suggest auditors are holding the line, but without public transparency, the probe risks being dismissed as a sham, further eroding the COA’s battered credibility.

Ombudsman’s Gavel: Justice or Bureaucratic Quagmire?

The Office of the Ombudsman Act (Republic Act No. 6770) empowers investigation of administrative or criminal liability under RA 3019, Sections 3(h) (pecuniary interest) or 3(e) (unwarranted benefits). Administrative sanctions like suspension or dismissal require only substantial evidence, but criminal graft demands proof beyond reasonable doubt of “manifest partiality” or “bad faith,” a steep hurdle per Henry T. Go (G.R. No. 172602, 2007). The Ombudsman’s independence is its strength, but political pressures and case backlogs could stall justice, leaving Lipana in purgatory.

Impeachment: A Political Apocalypse

Impeachment is a constitutional inferno, sparked by a one-third House vote and tried in the Senate (Article XI, Section 3). Rep. Leila de Lima’s threat invokes “betrayal of public trust,” a ground upheld in In re: Impeachment of Chief Justice Renato Corona (2012). Estrada v. Desierto (G.R. No. 146710-15, 2001) shows impeachment’s power to oust, but political will is a fickle beast.

With the House divided and elections looming in 2025, the Senate’s two-thirds threshold is a mountain too steep for a scandal this nuanced. Impeachment is a spectacle, not a scalpel, risking division over resolution.

The Quiet Retreat: Resignation’s Hollow Victory

Lipana could resign, as Rep. Antonio Tinio demands, echoing Aguinaldo v. Santos (G.R. No. 94115, 1992), where officials stepped down to quell controversies. But resignation doesn’t erase liability—RA 3019 prosecutions or civil suits could pursue him, and public distrust would linger like a specter, unappeased by his exit.

The Price of Betrayal: Punishments That Scar

If guilt is proven, the consequences are a brutal reckoning for Lipana and the COA’s soul.

- Administrative: The Ombudsman could suspend or dismiss Lipana under RA 6770, Section 21, for violating RA 6713’s ethical standards. Suspension pending impeachment would be a public shaming, marking him unfit while inquiries grind on.

- Criminal: An RA 3019 conviction under Section 3(h) brings 1-10 years in prison, perpetual disqualification from office, and asset forfeiture (Section 9). The Sandiganbayan’s verdict would echo as a warning: even constitutional guardians aren’t above the law.

- Civil: The government could sue to recover the P326 million paid to Olympus, voiding contracts under RA 3019, Section 9, or the Government Procurement Reform Act (Republic Act No. 9184). COA’s notices of disallowance are the opening shot, demanding restitution that could cripple the firm and tarnish Lipana’s name.

- Institutional: The deepest scar is to the COA’s credibility. Urbano v. Government Service Insurance System (G.R. No. 137904, 2001) warned of the chaos conflicts sow in public office. A tainted commissioner risks turning the COA into a hollow shell, its audits dismissed as compromised.

The Final Judgment: A Call to Arms and a Dark Prophecy

Lipana must act decisively: recuse himself from all matters involving Olympus or the DPWH, disclose his and his wife’s financials, and resign to spare the COA further damage. Divestment within 60 days, per RA 6713, Section 9, is the bare minimum, but only resignation honors the Constitution’s ironclad mandate.

Cordoba must abandon his spineless hedging, launching a transparent COA fact-finding panel within weeks and referring findings to the Ombudsman immediately. His “medyo meron” evasions must yield to resolve, or he risks being branded complicit. Congress should hold off on impeachment, letting the Ombudsman’s probe unfold, but a House inquiry to pressure COA accountability is essential.

The prognosis, rooted in Philippine political realities, is bleak. If no evidence of Lipana’s intervention emerges, recusal and divestment may quiet the storm, but public trust will erode, fueled by X’s relentless outrage. If auditors uncover influence or profit, the Ombudsman will file RA 3019 charges, and Lipana’s career will end in disgrace—though political inertia may delay impeachment.

The COA, battered by scrutiny, will limp forward, its mandate tarnished until bold reforms restore its honor. This is no mere conflict; it’s a constitutional wound, and only fearless action can stop the bleeding.

Key Citations

- 1987 Constitution, Article IX, Section 2: Prohibits COA commissioners from financial interests in government contracts.

- Republic Act No. 3019, Sections 3(h), 3(e), 9: Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, addressing pecuniary interests and penalties.

- Republic Act No. 6713, Sections 4(a), 7(a), 9: Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials.

- Republic Act No. 9184: Government Procurement Reform Act, governing contract awards.

- Republic Act No. 6770: Office of the Ombudsman Act, outlining investigative powers.

- COA Resolution No. 2018-010 (PDF): COA’s ethical code for integrity and independence.

- Republic v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. No. 152154, 2003): Requires proof of actual gain for graft convictions.

- Civil Liberties Union v. Executive Secretary (G.R. No. 83896, 1991): Broadly interprets prohibitions on financial interests.

- Public Interest Center, Inc. v. Elma (G.R. No. 138965, 2006): Demands swift action for commission integrity.

- Henry T. Go (G.R. No. 172602, April 13, 2007): Sets high bar for RA 3019 convictions.

- Estrada v. Desierto (G.R. No. 146710-15, 2001): Affirms impeachment’s power to remove.

- Urbano v. Government Service Insurance System (G.R. No. 137904, 2001): Warns of conflicts’ harm to public office.

- In re: Impeachment of Chief Justice Renato Corona (A.M. No. 20-07-10-SC, 2012): Upholds betrayal of public trust as impeachment ground.

- Aguinaldo v. Santos (G.R. No. 94115, 1992): Notes resignation as a scandal resolution.

- Gonzales v. Office of the President (G.R. No. 196231, 2014): Clarifies limits on intra-branch discipline.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

- $2 Trillion by 2050? Manila’s Economic Fantasy Flimsier Than a Taho Cup

Leave a comment