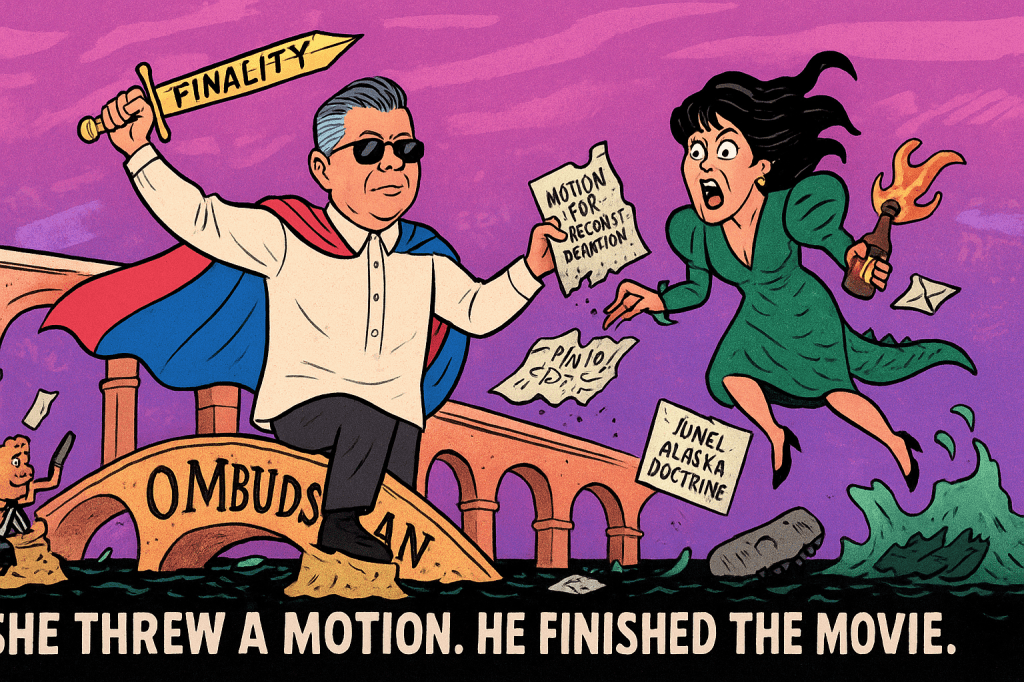

With a Motion for Reconsideration filed faster than a speeding bullet, Imee Marcos tries to stall Remulla’s Ombudsman dreams—only to crash into the brick wall of finality.

By Louis ‘Barok’ C Biraogo — September 13, 2025

Introduction: A Political Thriller Masquerading as a Legal Skirmish

Cue the suspenseful music: Senator Imee Marcos has lobbed a Motion for Reconsideration (M.R.) like a grenade into the heart of Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin Remulla’s bid for the Ombudsman’s chair. The Ombudsman, armed with the razor-sharp blade of due process, has already obliterated Imee Marcos’s complaints—allegations of graft, usurpation of authority, and grave misconduct tied to the Rodrigo Duterte International Criminal Court (ICC) transfer—with a dismissal so decisive it could star in a legal textbook. Yet Imee Marcos, ever the political maestro, insists her M.R. keeps the case “pending,” a claim as brittle as a sandcastle at high tide. This isn’t legal strategy; it’s a blockbuster political drama, and we’re here to shred it with the precision of a legal sniper and the wit of a fed-up commentator. Buckle up—Marcos’s gambit doesn’t stand a chance.

Marcos’s M.R.: A Desperate Ploy Doomed to Implode

Senator Marcos’s Motion for Reconsideration isn’t a legal lifeline; it’s a political Molotov cocktail, hurled in a panic to stall Remulla’s ascent. Filed on the same day the Ombudsman’s joint resolution dismissed her complaints, it reeks of reflex, not reason. Administrative Order No. 07, Series of 1990, Section 7, allows one M.R., to be filed within five days of notice. Marcos squeaked in under the wire, but timeliness doesn’t mask a lack of substance. Her motion is a procedural last gasp, a calculated attempt to clog the Judicial and Bar Council (JBC)’s nomination pipeline. It’s not about justice—it’s about sabotage.

Imee Marcos argues her M.R. keeps the case “pending,” blocking Remulla’s Ombudsman clearance. This is legal fiction dressed in bold font. The Ombudsman’s dismissal, likely grounded in a lack of probable cause or jurisdictional overreach, is the final word. The M.R. is a mere echo, a frivolous attempt to revive a case already buried. Under A.O. No. 07, the Ombudsman’s discretion to dismiss baseless complaints is near-absolute, and Imee Marcos’s failure to establish a prima facie case—perhaps due to weak evidence or mischaracterized offenses—dooms her motion to the ash heap. Her claim that the case remains “pending” is as absurd as insisting a knockout punch didn’t end the fight because the loser’s still twitching.

Worse, Imee Marcos’s motives betray her. Filing an M.R. with lightning speed suggests not a reasoned critique but a premeditated plot to weaponize the Ombudsman’s process. Republic Act No. 6713, the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees, demands that public officials avoid conduct prejudicial to the service. Squandering public resources on a frivolous motion to score political points? That’s not just prejudicial—it’s a masterclass in bad faith. Marcos isn’t seeking justice; she’s staging a coup against Remulla’s nomination.

The Law: Remulla’s Victory Sealed in Steel-Clad Precedent

On the legal front, Remulla stands on a fortress of unassailable precedent, while Imee Marcos’s arguments crumble like a poorly drafted pleading. The Ombudsman’s dismissal of her complaints is a textbook exercise of due process, backed by the Supreme Court’s ruling in Junel Alaska et al. v. SPO2 Gil M. Garcia et al. (G.R. No. 228298, 2021), which declares Ombudsman decisions absolving respondents final, executory, and unappealable. Full stop. Marcos’s M.R. doesn’t suspend this finality; it’s a procedural footnote, a single shot permitted under A.O. No. 07, Section 7, that’s already missed its mark. The Supreme Court has long upheld the Ombudsman’s broad discretion to dismiss baseless complaints (Uy v. Sandiganbayan, G.R. No. 105965, 2001), and Imee Marcos offers no evidence of grave abuse of discretion—a threshold she can’t even glimpse.

Imee Marcos’s insistence that her M.R. renders the case “pending” for JBC purposes is a legal mirage. A “pending case” implies an active, unresolved complaint with a viable path to prosecution. A dismissed case, even with an M.R., is a closed chapter. The JBC’s clearance requirement, as clarified by Supreme Court pronouncements, hinges on the absence of an active complaint. The Ombudsman’s joint resolution, dismissing both administrative and criminal charges, satisfies this. Imee Marcos’s M.R. isn’t a case; it’s a tantrum, and the JBC isn’t obligated to entertain it. To rule otherwise would let any complainant paralyze nominations with endless, meritless motions—a legal absurdity that would gut the Ombudsman’s authority.

The presumption of regularity seals Remulla’s position. The Ombudsman, tasked with investigating public officials under Republic Act No. 6770, is presumed to have acted lawfully in dismissing the complaints (Pajaro v. Sandiganbayan, G.R. No. 82001 (April 15, 1988). Marcos offers no proof of grave abuse—only political noise. Her allegations, tied to the Duterte ICC transfer, likely failed for lack of jurisdiction or evidence, as the Ombudsman’s mandate doesn’t extend to second-guessing executive actions absent clear illegality. Remulla, as Justice Secretary, acted within his lawful authority, and the Ombudsman’s dismissal reflects that reality.

The Political Circus: Marcos’s Gambit Unmasked

Zoom out to the narrative stage, where Imee Marcos’s ploy reveals itself as a political circus, not a legal battle. In a move that shocked precisely no one, Senator Marcos has rushed to the wreckage of her dismissed complaints, frantically trying to resuscitate a case that’s already six feet under. Her accusations—graft, usurpation, misconduct—are a recycled playlist from the Duterte-era grudge match, aimed at smearing a rising star in the administration. The lightning-fast filing of her M.R. betrays its true purpose: to stall Remulla’s Ombudsman bid and paint him as tainted before the JBC and the public.

This isn’t about accountability; it’s about power. Imee Marcos, a political veteran, knows the JBC’s clearance process is a choke point. By keeping her complaint “alive” with an M.R., she hopes to force the JBC to hesitate and the public to doubt. It’s a cynical maneuver, using the Ombudsman’s process as a political battering ram. The irony is delicious: Marcos claims to protect the Ombudsman’s integrity while turning it into a prop for her vendetta. Her actions violate the spirit of RA 6713, undermining public trust in the very institution she claims to defend.

The stakes are seismic. If the Ombudsman caves to Imee Marcos’s pressure and delays clearance, it hands a victory to political sabotage, eroding its independence. If the JBC wavers, it risks setting a precedent where any dismissed complaint can be revived by a frivolous M.R., paralyzing the nomination process. Worst of all, it denies Remulla his right to be considered for office free from baseless obstacles—a violation of fairness that reeks of political revenge.

Conclusion: The Ombudsman Must Slay the Dragon

The Ombudsman must stand firm, its sword of due process gleaming. Its dismissal of Imee Marcos’s complaints is legally bulletproof, anchored in A.O. No. 07 and fortified by Junel Alaska et al. v. SPO2 Gil M. Garcia et al. (G.R. No. 228298, 2021). Issuing Remulla’s clearance now isn’t just permissible—it’s a moral and legal imperative, a stand against political manipulation. Imee Marcos’s M.R. is a distraction, not a legal barrier. To delay clearance would reward bad faith and weaken the Ombudsman’s authority.

Let’s call it what it is: Marcos’s motion isn’t a legal argument; it’s a political tantrum typed in 12-point font. She’s not fighting for justice but for chaos, hoping to tarnish Remulla’s bid with the illusion of a “pending” case. The Ombudsman must slay this dragon, issue the clearance, and let the JBC proceed. Anything less is a surrender to a farce that threatens the rule of law. Remulla’s path to the Ombudsman’s office is clear—Imee Marcos’s theatrics be damned.

Key Citations

- Administrative Order No. 07, Series of 1990, Section 7: Limits motions for reconsideration to one, to be filed within five days, and governs Ombudsman procedure.

- Junel Alaska et al. v. SPO2 Gil M. Garcia et al., G.R. No. 228298 (2021): Ombudsman decisions absolving respondents are final, executory, and unappealable.

- Uy v. Sandiganbayan, G.R. No. 105965 (2001): Affirms Ombudsman’s broad discretion in dismissing complaints absent grave abuse.

- Pajaro v. Sandiganbayan, G.R. No. 82001 (April 15, 1989): Upholds presumption of regularity in Ombudsman actions.

- Republic Act No. 6713 (1989): Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards, prohibiting conduct prejudicial to the service.

- Republic Act No. 6770 (1989): Ombudsman Act, defining the Ombudsman’s powers and duties.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment