By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — September 17, 2025

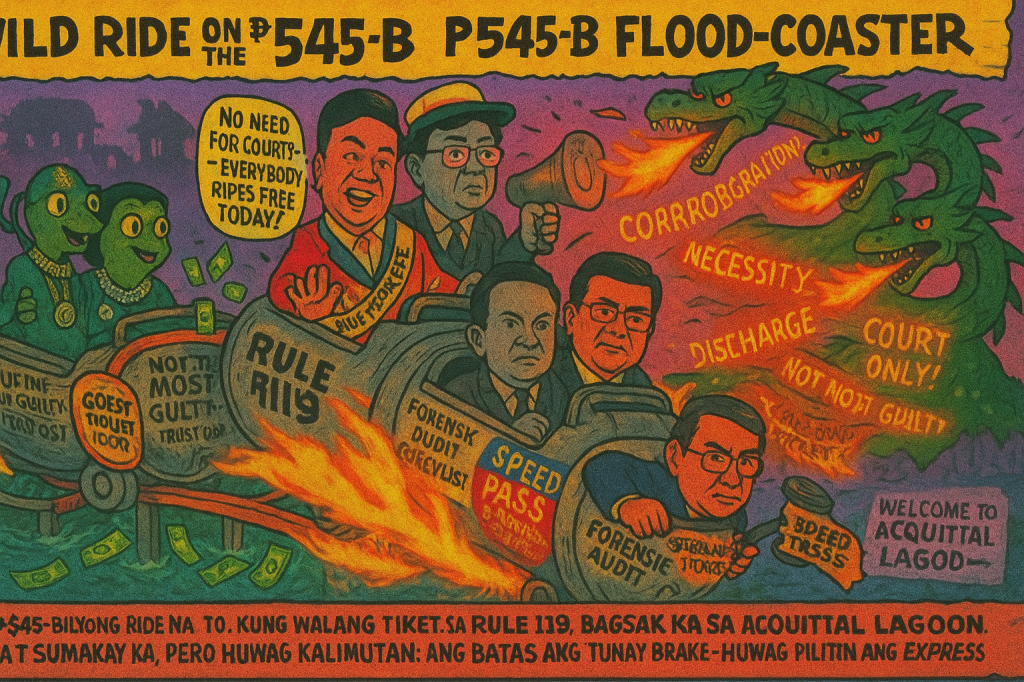

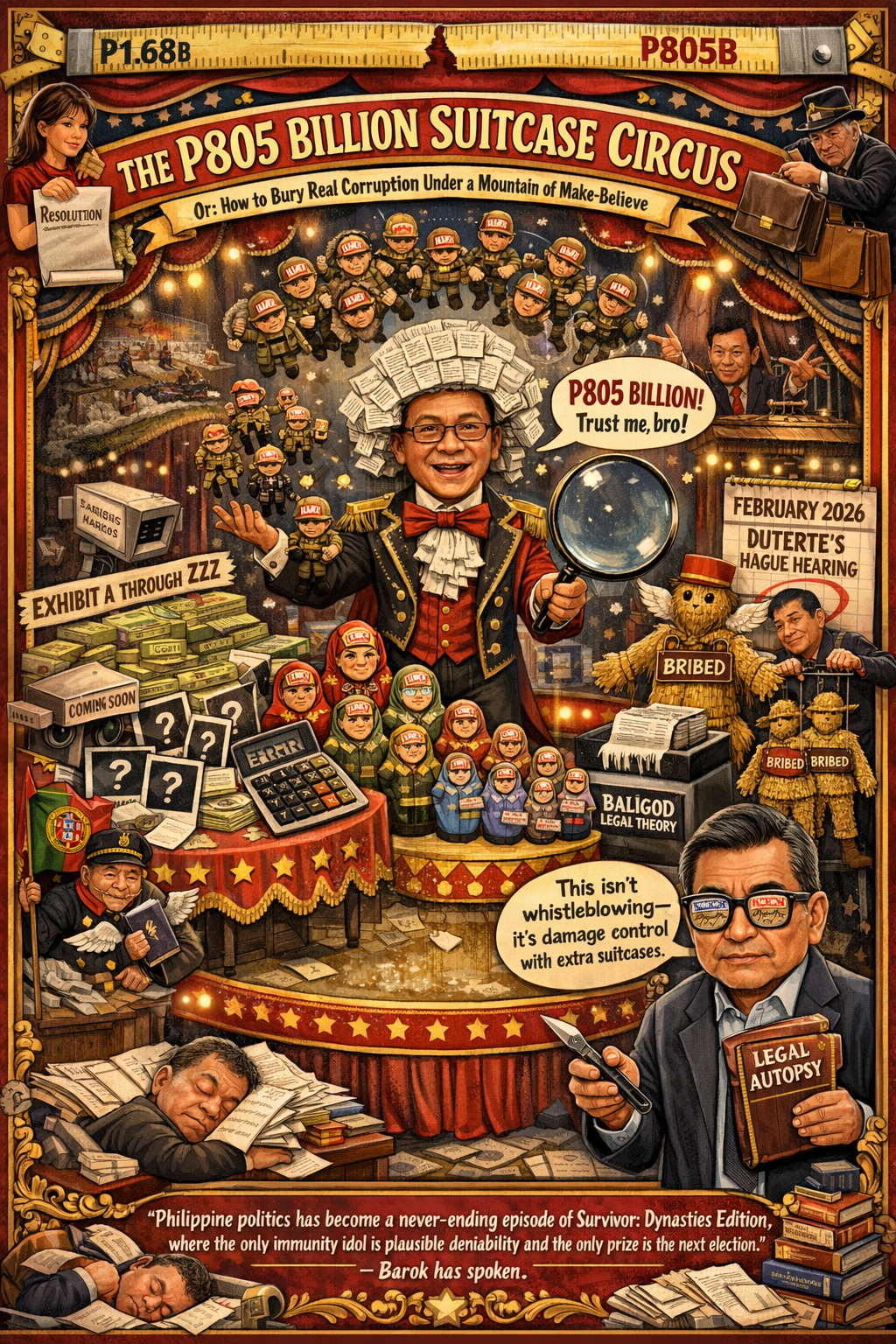

STEP right in, brave soul, to a spectacle of legal jousting, political theatrics, and a corruption scandal so vast it could swallow Manila whole. The clash between Senator Rodante Marcoleta, Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin Remulla, and contractors Curlee and Sarah Discaya over the flood control scandal is a masterclass in hubris and hypocrisy. With ₱545 billion in public funds allegedly squandered on ghost projects and rigged bids, this drama demands a surgical takedown. Armed with the wit of a courtroom jester and the precision of a legal assassin, Kweba ni Barok slices through the noise using the B.R.E.A.K. framework—because nothing exposes rot like a sharp pen and sharper laws.

B: Slicing the Scandal into Bite-Sized Chunks

The Marcoleta-Remulla-Discaya dispute is a legal and ethical minefield, threatening to derail accountability for a massive corruption scheme. Using the B.R.E.A.K. framework (Break, Review, Establish, Address, Keep), we’ll dissect the legal arguments, expose ethical failures, unravel the scandal’s implications, and propose solutions sharper than a guillotine.

R: Unmasking the Players in This Legal Soap Opera

1. Marcoleta and the Discayas: A Shameless Power Grab or Whistleblower Salvation?

Senator Rodante Marcoleta’s crusade to fast-track Curlee and Sarah Discaya into the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Witness Protection Program (WPP) under Republic Act No. 6981 (R.A. 6981) is a brazen overreach. He demands their immediate admission, citing threats and their Senate Blue Ribbon Committee testimony exposing alleged flood control anomalies. But hold your breath, dear reader, for the plot twists: Rule 119, Sections 17-19 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure clearly grant courts—not senators—the power to discharge an accused as a state witness. Section 17(d) demands the accused “does not appear to be the most guilty,” and Section 17(c) requires “substantially corroborated” testimony. Marcoleta’s urgency sidesteps these, as if he’s rewriting the law on live TV. Has he even glanced at the rules he so boldly invokes?

- Marcoleta’s Ethical Faceplant: His claim of an “informal assurance” from Remulla reeks of a violation of Republic Act No. 6713 (R.A. 6713, Section 4(c)), the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees, which mandates professionalism and bars undue influence. Leaning on a personal friendship (“matagal kaming nagsama”) to pressure the DOJ? That’s not just bad form—it’s an ethical trainwreck. The Supreme Court’s ruling in People v. Sunga (G.R. No. 126029, 2003) reminds us that discharge is a judicial prerogative, and legislative meddling risks tainting justice.

- The Discayas’ Dubious Tell-All: The Discayas, flaunting 40 luxury vehicles worth ₱300-465 million, are no saints blowing the whistle. Their sudden eagerness to testify—after allegedly profiting from substandard or ghost flood control projects—screams opportunism. Do they meet Rule 119’s “not the most guilty” criterion? Not when their car collection suggests they were swimming in the corruption pool. People v. Ferrer (G.R. No. 148821, 2003) demands corroborated testimony, yet the Discayas’ claims lack forensic heft. Are they spilling secrets or scripting a getaway?

2. Remulla: Guardian of Justice or Bureaucratic Obstructionist?

Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin Remulla’s caution, insisting on forensic accounting and a rigorous WPP process under R.A. 6981, is legally sound but politically disastrous. Section 10 of the Act grants the DOJ discretion to evaluate WPP applicants based on testimony necessity and credibility—prudent, given the Discayas’ shaky candor. People v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. Nos. 185729-32, 2013) reinforces that discharge under Rule 119 requires meeting strict requisites. But Remulla’s demand for returning ill-gotten wealth, absent from R.A. 6981‘s text, smells of extra-legal overreach. Is he protecting justice or building a moat around it?

- Political Blunder: Remulla’s public denial of any “assurance” to Marcoleta, if Marcoleta’s claim is true, paints him as a flip-flopper, chilling potential whistleblowers and undermining R.A. 6981‘s protective purpose. Webb v. De Leon (G.R. No. 121234, 1995) warns against prosecutorial delays that endanger witnesses. By publicly doubting the Discayas, Remulla risks silencing others who could expose the flood control racket.

- Inter-Branch Tensions: If Marcoleta’s “assurance” claim holds water, Remulla’s backtracking violates R.A. 6713, Section 4(b), on commitment to public interest. This public spat erodes trust between the Senate and DOJ, a cardinal sin when rooting out corruption.

3. The Flood Control Scandal: A ₱545-Billion House of Cards

This dispute isn’t just a sideshow—it’s a seismic tremor in the ₱545-billion flood control scandal. The Senate Blue Ribbon Committee’s findings expose a cesspool: thousands of substandard or ghost projects, with 15 contractors pocketing 20% of the budget. This is “grand corruption” on a biblical scale, implicating congressmen, Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) officials, and potentially higher-ups across administrations.

- Evidence in Peril: If the Discayas are silenced—by threats or distrust—key evidence could vanish, derailing prosecutions under Republic Act No. 3019 (R.A. 3019, Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act). Section 3(e) targets “manifest partiality” and “undue advantage,” exactly what the Discayas’ testimony could prove. Delay risks acquittals, as seen in Disini v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. No. 169823, 2013).

- Whistleblower Freeze: Remulla’s skepticism could deter others from coming forward, gutting R.A. 6981‘s goal of encouraging disclosures. Protected, the Discayas could unravel a network of kickbacks, potentially triggering plunder charges under Republic Act No. 7080 (R.A. 7080) for amounts over ₱50 million.

- Political Quagmire: This feud fuels a narrative of obstruction versus witch-hunt, pitting Marcos against Duterte allies. Social media whispers suggest Marcoleta’s probe dodges Duterte-era anomalies, protecting cronies while pointing fingers elsewhere.

4. Escaping the Mire: Bold Solutions to Save the Day

To navigate this legal swamp, here’s a roadmap rooted in law and pragmatism:

- DOJ: Act Fast, Act Fair

Expedite a forensic audit to corroborate the Discayas’ claims, but provide interim WPP protection if threats are verified (R.A. 6981, Sec. 8). Publish a transparent timeline to silence cries of obstruction. People v. Court of Appeals (G.R. No. 108000, 1993) demands procedural fairness, not bureaucratic quicksand. - Senate: Stick to Your Lane

Formalize evidence referral to the Office of the Ombudsman with judicial affidavits and threat documentation to bolster R.A. 3019 cases. Marcoleta must cease promising legal outcomes—his role is to probe, not prejudge. - Courts: Guard the Gates

When discharge motions arise, apply Rule 119‘s requisites with an iron fist. People v. Sunga demands corroboration and necessity; courts must ensure the Discayas aren’t gaming the system. - Public: Demand the Truth

Push for independent monitoring of the audit process under R.A. 6713. Transparency ensures neither protection nor prosecution becomes a political pawn. - Systemic Overhaul: Strengthen the Ombudsman, enforce transparent procurement under Republic Act No. 9184 (R.A. 9184), and uphold judicial gatekeeping under Rule 119 to prevent future scandals.

E: Setting the Stage for Justice

Each section targets a clear goal:

- Marcoleta/Discayas: Expose their overreach using Rule 119 and R.A. 6713, affirming judicial supremacy.

- Remulla: Validate his caution but skewer his political missteps, grounded in R.A. 6981 and precedents.

- Implications: Link the dispute to the scandal’s stakes, emphasizing risks to evidence and trust under R.A. 3019.

- Recommendations: Chart a path balancing witness safety with prosecutorial rigor, rooted in law and public interest.

A: Weaving the Web of Accountability

The legal arguments drive the scandal’s fate: Marcoleta’s overreach breeds perceptions of bias, while Remulla’s caution risks losing evidence. Both threaten whistleblower confidence and R.A. 3019 prosecutions. Recommendations align DOJ discretion with judicial oversight, ensuring the scandal doesn’t drown in political mudslinging.

K: Crafting a Cohesive Call to Arms

This saga mirrors the Philippines’ anti-corruption struggle: a clash of legal precision, political ambition, and systemic decay. The Discayas, with their luxury cars and convenient confessions, are less whistleblowers than survivors, yet their testimony could crack open a ₱545-billion scandal. Marcoleta’s zeal risks judicial overreach, while Remulla’s caution teeters on obstruction. Both wield R.A. 6981 and Rule 119 as weapons, but neither grasps the public’s thirst for justice.

The Final Reckoning: Drain the Swamp or Drown in It

Dear reader, the flood control scandal isn’t just about ghost projects—it’s about a nation drowning in corruption while its leaders squabble over legal scraps. The Marcoleta-Remulla-Discaya fiasco proves the law is only as strong as its enforcers. Will we let this scandal sink into political theater, or will we demand accountability? The Ombudsman, courts, and public must rise, armed with R.A. 3019‘s teeth and Rule 119‘s rigor. Let’s drain the swamp before it floods us all.

Barok out.

Key Citations

- Republic Act No. 6981 (Witness Protection, Security and Benefit Act): Governs the WPP, vesting implementation in the DOJ.

- Republic Act No. 6713 (Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards): Sets ethical standards for public officials, prohibiting undue influence

- Republic Act No. 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act): Criminalizes corrupt practices like partiality and undue advantage.

- Republic Act No. 7080 (Plunder Law): Defines plunder for amounts over ₱50 million..

- Republic Act No. 9184 (Government Procurement Reform Act): Governs transparent procurement.

- Rule 119, Sections 17-19 (Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure): Governs state witness discharge.

- People v. Sunga (G.R. No. 126029, 2004): Affirms judicial role in discharge.

- People v. Ferrer (G.R. No. 148821, 2003): Requires corroborated testimony for discharge.l.

- People v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. Nos. 185729-32, 2013) – Affirms Rule 119’s strict requisites.

- Webb v. De Leon (G.R. No. 121234, 1995): Warns against prosecutorial delays endangering witnesses.

- People v. Court of Appeals (G.R. No. 108000, 1993): Demands procedural fairness.

- Disini v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. No. 169823, 2013): Highlights weak evidence risks in graft cases.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

Leave a comment