By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — September 20, 2025

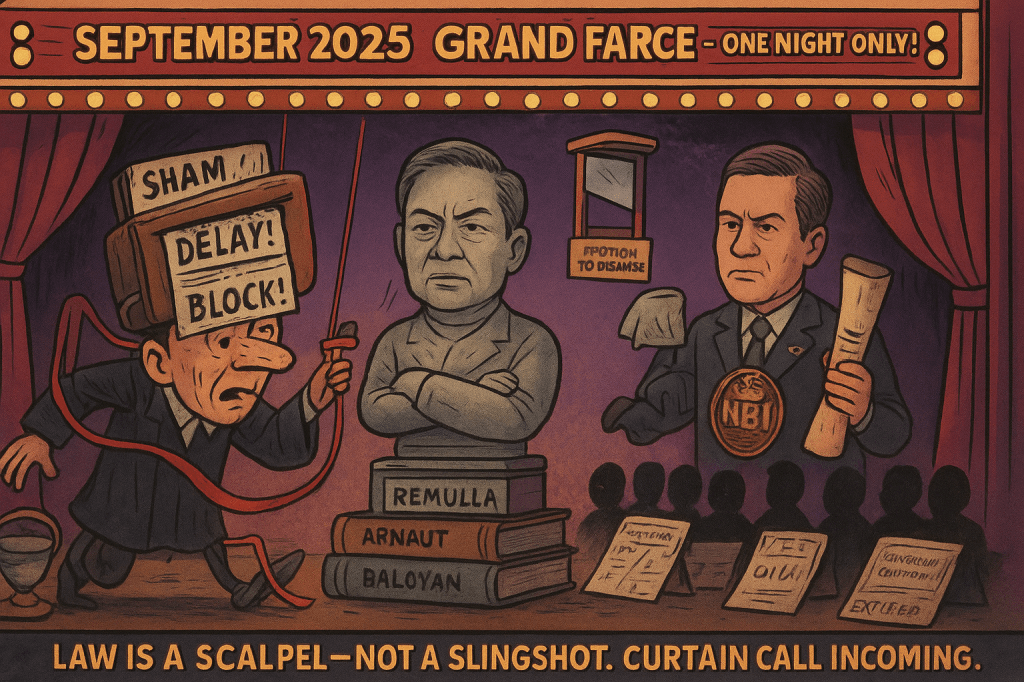

BEHOLD the grand stage of Ferdinand Topacio’s latest charade, where lawsuits masquerade as political grenades! In a move as subtle as a sledgehammer, Topacio has unleashed a 20-page complaint at the Office of the Ombudsman, accusing Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin “Boying” Remulla and former National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) Director Jaime Santiago of arbitrary detention and graft. The timing? A suspiciously choreographed September 2025, perfectly aligned to sabotage Remulla’s bid for Ombudsman. The substance? A flimsy, recycled grievance over the 2024 arrests of Sheila Guo and Cassandra Li Ong, served with a heaping dose of sanctimonious bluster. Spoiler: this isn’t about justice—it’s a brazen ambush, designed for maximum media splash and minimum legal merit, that’s about to get shredded faster than a losing lottery ticket.

Surgical Strike: Dissecting Topacio’s Feeble Case

Let’s grab the scalpel and carve into Topacio’s complaint, exposing its hollow innards. He alleges arbitrary detention under Article 124 of the Revised Penal Code (RPC) and graft under Republic Act (RA) 3019. Both charges are so legally frail, they’d collapse under a stiff breeze. Here’s the vivisection.

Arbitrary Detention (Art. 124, RPC): A Baseless Whine

Topacio wails that the arrests of Guo and Ong were warrantless and baseless, casting Remulla and Santiago as rogue jailers. Spare us the melodrama. The arrests were the lawful execution of congressional contempt orders—a Senate arrest warrant for Guo’s no-show at Philippine Offshore Gaming Operator (POGO) inquiries and a House contempt citation for Ong. The Supreme Court has long upheld Congress’s inherent contempt powers as a constitutional cornerstone for legislative inquiries (Arnault v. Nazareno, G.R. No. L-3820, 1950). These powers, enshrined in Article VI, Section 11 of the 1987 Philippine Constitution, allow Congress to enforce its mandates, including via executive assistance. The NBI’s role? Purely custodial, carrying out lawful orders, not orchestrating some lawless lockup. Ampatuan v. Macaraig (G.R. No. 182497, 2010) slams the door on Topacio’s claim, affirming that detentions grounded in valid orders are not arbitrary. Art. 124 requires detention without legal basis—here, the basis is as solid as Rizal’s monument, with the Senate’s warrant and the House’s citation as undeniable proof. Topacio’s argument? A legal fiction, ignoring the paper trail.

Graft (RA 3019): A Laughable Leap

Topacio’s graft charge is a masterclass in overreach, alleging Remulla and Santiago caused “undue injury” or acted with “manifest partiality” by enforcing congressional orders. Let’s unpack this absurdity. RA 3019, Section 3(e) demands proof of corrupt intent, undue benefit, or tangible injury (Republic Act No. 3019). What’s the injury? Upholding the law? Coordinating with Congress to detain individuals dodging legislative probes? Arias v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. No. 81563, 1989) is unequivocal: good-faith performance of official duties negates graft. Remulla, as Department of Justice (DOJ) Secretary, and Santiago, as NBI Director, were executing core law enforcement functions, not chasing personal gain. Topacio’s complaint fails to pinpoint a single peso of illicit benefit or a whiff of corrupt motive. Instead, it flounders, hoping procedural quibbles will pass for criminality. Albert v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. No. 164015, April 29, 2005) warns against conflating administrative slip-ups with graft—Topacio’s fishing expedition doesn’t even breach the surface of RA 3019’s evidentiary threshold.

The Smoking Gun: A Year-Late Political Assassination

The complaint’s one-year delay isn’t a mere footnote; it’s a blazing red flag screaming “political hit job.” Filed in September 2025, over a year after the August 2024 arrests, this lawsuit stinks of opportunism, timed to derail Remulla’s Ombudsman bid. Topacio’s flimsy excuse? New facts or witnesses, he claims. Really? The same Topacio who once lauded Santiago’s integrity now flips like a pancake when it suits his agenda? This isn’t advocacy; it’s a betrayal of Canon III, Section 1 of the Code of Professional Responsibility and Accountability (CPRA), demanding candor and fairness. While the delay falls within the three-year prescription for Art. 124 (RPC, Art. 90) and ten-year for RA 3019 (Section 11), it exposes Topacio’s true aim: weaponizing the Ombudsman’s process to block Remulla’s Judicial and Bar Council (JBC) clearance. Spouses Manuel A. Aguilar and Yolanda C. Aguilar v. Manila Banking Corporation (G.R. No. 157911, September 19, 2006) condemns such dilatory tactics, and Topacio’s sudden volte-face only amplifies the stench of bad faith.

Topacio’s Endgame: Weaponizing the JBC’s Machinery

Let’s strip away the veneer: Topacio’s complaint isn’t a quest for justice—it’s a political grenade lobbed to explode Remulla’s Ombudsman bid. The JBC requires an Ombudsman clearance certifying no pending criminal or administrative cases (JBC Rules, Rule 4, Section 5). A single filed complaint, regardless of merit, can stall that clearance, effectively sidelining Remulla from the shortlist. Topacio’s strategy is as cynical as it is transparent: exploit the JBC’s bureaucratic chokehold to delay or derail a formidable candidate. The legal merits? Utterly irrelevant. The mere existence of a pending case is the weapon, wielded to sabotage Remulla’s nomination while cloaking the attack in pious legalese.

This is a textbook abuse of process, violating CPRA Canon IV, Section 1’s prohibition on frivolous suits meant to harass. Topacio isn’t fighting for Guo or Ong; he’s a hired gun for unseen forces terrified of a Remulla-led Ombudsman that would pursue corruption with unrelenting zeal. By flooding the Ombudsman with a verbose screed, he’s banking on bureaucratic gridlock to do the dirty work—delay the clearance, tank the bid, and slink away. It’s not lawyering; it’s legal extortion.

Fortifying the Castle: Remulla’s Battle Plan

Remulla must counter with a strategy as sharp as a guillotine. Here’s the playbook to obliterate Topacio’s sham:

1. Motion to Dismiss with Extreme Prejudice:

File an immediate motion to dismiss with the Ombudsman, arguing no prima facie case exists. For Art. 124, the Senate warrant and House citation provide ironclad legal grounds, rendering the charge baseless. For RA 3019, the absence of corrupt intent or undue injury—bolstered by Arias’s good-faith defense—makes the graft claim a non-starter. People v. Dumlao (G.R. No. 168918, 2009) supports quashing complaints lacking evidentiary foundation. Speed is critical to secure the JBC clearance before the shortlist deadline.

2. Presumption of Regularity: The Iron Shield:

Lean hard into the doctrine of presumption of regularity. Public officials like Remulla and Santiago are presumed to act lawfully (Yap v. Lagtapon, G.R. No. 196347 (2017)). Topacio bears the burden of proving otherwise—a burden his complaint fails to meet with its vague allegations and zero evidence of malice. Produce NBI logs, congressional orders, and timelines showing compliance with Rule 113 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure and RA 7438 (Rights of Persons Arrested, Detained or Under Custodial Investigation) to bury the arbitrary detention claim.

3. Seize the Narrative: Go Nuclear:

Take the fight to the public square. Frame Topacio’s complaint as a desperate smear by those fearing a no-nonsense Ombudsman. Remulla’s anti-corruption record and DOJ leadership make him a prime target for shadowy players protecting their fiefdoms. Press statements should underscore the arrests’ alignment with POGO probes—public interest, not personal vendetta. RA 6713, Section 4(a) (Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials) backs Remulla’s duty to prioritize the public good.

Execute this trifecta, and Topacio’s complaint will implode faster than a bad sitcom.

The High Stakes: A Threat to Justice Itself

The implications of Topacio’s gambit are nothing short of apocalyptic. If a frivolous, last-minute complaint can derail a qualified Ombudsman candidate, the JBC process becomes a playground for bad-faith actors. Every future nomination could face a tsunami of sham lawsuits, turning a constitutional safeguard into a political punching bag. Republic v. Sereno (G.R. No. 237428, 2018) underscored the paramount importance of integrity in high office—allowing Topacio’s tactics to succeed would mock that principle, gutting the Ombudsman’s role as a corruption watchdog. The fallout? A weakened DOJ, intensified scrutiny on POGO probes, and a Marcos administration navigating a political minefield. This isn’t just about Remulla; it’s about the soul of the rule of law.

The Final Blow: Topacio’s Farce Faces Oblivion

Topacio’s complaint is a legal sandcastle, doomed to crumble under the tide of scrutiny. The Ombudsman will likely dismiss it faster than a judge rejecting a typo-ridden brief. The Senate’s warrant and the House’s citation eviscerate the arbitrary detention charge; the absence of corrupt intent decapitates the graft claim. Remulla’s team need only present the paper trail—congressional orders, NBI logs, compliance records—to expose Topacio’s filing as a political stunt in legal drag.

Recommendation: The Ombudsman should not only dismiss this travesty but also consider sanctions against Topacio under CPRA Canon IV for squandering public resources on a complaint that’s more about headlines than justice. Let this be a clarion call to future legal mercenaries: the law is a scalpel, not a slingshot for petty vendettas. Remulla will rise from this ashes, his Ombudsman bid stronger than ever, ready to wield the office’s power against the very corruption Topacio’s allies seem desperate to shield. Curtains down, Ferdinand—your show’s over.

Key Citations

- PhilStar, September 18, 2025: NBI: Fresh raps challenge Remulla’s ombudsman bid

- Arnault v. Nazareno, G.R. No. L-3820, 1950: Upholds Congress’s inherent contempt powers for legislative inquiries.

Baloyan v. People, G.R. No. 153144, 2006:- Ampatuan v. Macaraig, G.R. No. 182497 (2010) – Validates detentions based on lawful orders, negating arbitrary detention claims.

- Arias v. Sandiganbayan, G.R. No. 81563, 1989: Establishes good-faith performance as a defense against graft.

Fonacier v. Sandiganbayan, G.R. No. 50691, 1996:- Albert v. Sandiganbayan, G.R. No. 164015, April 29, 2005: Clarifies that procedural lapses don’t equate to graft without corrupt intent.

People v. Sandiganbayan, G.R. No. 140633, 2012:- Spouses Manuel A. Aguilar and Yolanda C. Aguilar v. Manila Banking Corporation, G.R. No. 157911, September 19, 2006: Condemns dilatory tactics in legal proceedings.

Cunanan v. Arceo, G.R. No. 116615, 1995:- Yap v. Lagtapon, G.R. No. 196347 (2017): Supports the presumption of regularity for public officials’ actions.

People v. Villareal, G.R. No. 201363, 2022:- People v. Dumlao, G.R. No. 168918 (2009): Allows quashing of complaints lacking prima facie evidence.

- Republic v. Sereno, G.R. No. 237428, 2018: Emphasizes integrity in high public office.

- 1987 Philippine Constitution, Article VI, Section 11: Grants Congress inquiry and contempt powers.

- Article 124 of the Revised Penal Code (RPC) – Defines the crime of arbitrary detention.

- Republic Act No. 3019, Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act: Defines graft and corruption offenses.

- Republic Act No. 7438, Rights of Persons Arrested: Outlines rights of detained persons.

- Republic Act No. 6713, Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards0: Sets ethical standards for public officials.

- Code of Professional Responsibility and Accountability (CPRA): Governs lawyer conduct and ethics.

- Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure, Rule 113: Governs arrest procedures.

- JBC Rules, Rule 2, Section 5 (PDF): Mandates Ombudsman clearance for nominations.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment