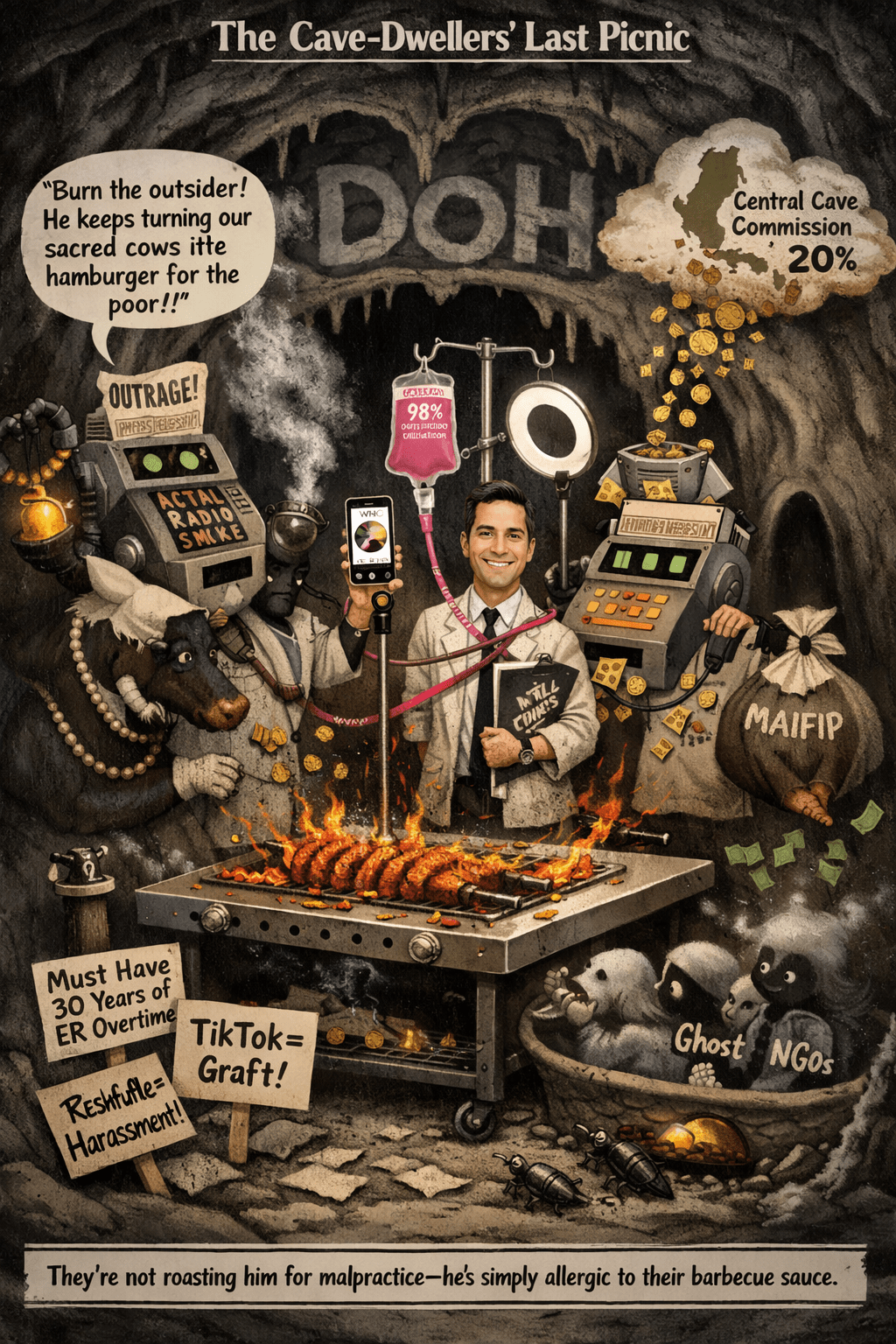

Can the Ombudsman Outwit a System Rigged for the Elite?

By Louis ‘Barok’ C Biraogo — October 9, 2025

THE stage is set for a legal circus. The spotlight shines on newly minted Ombudsman Jesus Crispin “Boying” Remulla, expected to juggle justice and chase Vice President Sara Duterte over her alleged misuse of ₱500 million in confidential funds. The crowd roars for accountability, but—plot twist!—the law slaps on the handcuffs, cackling, “Not so fast, hero!” Is Remulla doomed to perform in a constitutional straitjacket, or can he pull off a daring escape from this jurisdictional farce? Welcome to the Philippines’ accountability theater, where the powerful get VIP passes to dodge scrutiny. Let’s tear into this mess with a scalpel dripping with sarcasm.

I. The Great Accountability Hoax: What’s the Fuss About?

A viral Facebook post has the nation buzzing like a tabloid scandal, claiming Remulla’s hands are tied tighter than a bad lawyer’s alibi. It argues that Republic Act No. 6770 (R.A. 6770), the Ombudsman Act of 1989, bars him from pursuing Duterte unless an impeachment complaint is on the table. Worse, it suggests the Department of Justice (DOJ) is equally neutered, unable to investigate because prosecution might “indirectly” boot her from office. The post paints a grim scene: ₱500 million in public funds, poof, gone, while Duterte allegedly sips piña coladas behind a constitutional shield.

But is this the whole story, or just a half-baked legal melodrama? Let’s dissect the post’s claims, expose its blind spots, and reveal whether this system is a tragedy or a farce.

II. The Legal Funhouse: Navigating the Rules of This Absurd Game

A. The Constitution’s VIP Club for Untouchables

Article XI, Section 2 of the 1987 Philippine Constitution lists the exclusive guest list for impeachment: the President, Vice President, Supreme Court justices, members of constitutional commissions, and the Ombudsman. Removal is only for “culpable violation of the Constitution, treason, bribery, graft and corruption, other high crimes, or betrayal of public trust.” This isn’t just a rule—it’s a fortress, built to shield constitutional offices from meddling but doubling as a free pass for the powerful. The Supreme Court’s ruling in In Re: Gonzales v. Chavez (G.R. No. 97351, 1992) confirms that the President, an impeachable official, is immune from administrative discipline during tenure. By extension, this logic applies to the Ombudsman and others on the list, as reinforced by later cases like Funa v. Villar (G.R. No. 192791, 2012). Noble intent? Sure. Convenient for dodging accountability? Absolutely.

B. The Ombudsman Act: A Toothless Tiger in a Paper Cage

R.A. 6770, the Ombudsman Act, is the post’s star witness, and it roars with restrictions:

- Section 21: “The Office of the Ombudsman shall have disciplinary authority over all elective and appointive officials… except over officials who may be removed only by impeachment, Members of Congress, and Members of the Judiciary.”

- Section 22: “In all cases involving… officials removable only by impeachment, the Ombudsman may investigate only for the purpose of filing an impeachment complaint.”

In plain English: Remulla can’t suspend, fire, or spank Duterte administratively. He can investigate, but only if impeachment’s on the menu. The post gets an A+ for quoting this correctly, but it’s a damning indictment of a system that lets high rollers dodge the heat while lesser officials sweat.

C. The Supreme Court’s Greatest Hits: Precedents That Bind and Blind

The judiciary’s been busy building this legal labyrinth. Key cases include:

- Carpio-Morales v. Binay (G.R. No. 217126-27, 2015): Here’s the plot twist. The Ombudsman can conduct fact-finding investigations on impeachable officials without prosecuting, as long as it doesn’t lead to sanctions during their term. Remulla could dig into Duterte’s funds now to preserve evidence for later.

- Estrada v. Desierto (G.R. Nos. 146710-15, 2001): Criminal liability is paused, not erased. Once Duterte’s term ends, the Ombudsman or DOJ can pounce—assuming the evidence hasn’t mysteriously vanished.

- Funa v. Villar (G.R. No. 192791, 2012): No one can “indirectly” remove an impeachable official through backdoor sanctions. This bolsters the post’s DOJ argument but doesn’t slam the door shut entirely.

D. The Ethical Smokescreen: Public Trust or Public Jest?

Article XI, Section 1 of the 1987 Constitution proclaims, “Public office is a public trust.” Republic Act No. 6713 (Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees) doubles down, demanding transparency from all officials. Yet, the post’s fatalism—accepting Duterte’s six-year immunity—mocks this principle. If the Vice President can waltz away from scrutiny, “public trust” is just a bumper sticker on a broken system.

III. The Scalpel’s Slash: Shredding the Post’s Half-Baked Narrative

A. Where the Post Nails It

The post is dead-on about R.A. 6770‘s limits. Duterte, as an impeachable official, is untouchable for administrative discipline. With the Supreme Court allegedly dismissing her impeachment complaint, Remulla’s stuck in neutral—no impeachment, no probe. This isn’t just a legal quirk; it’s a neon sign screaming, “High officials get a free pass!” The post deserves a nod for exposing this, even if it’s a bitter truth.

B. Where It Trips Over Its Own Ego

But the post stumbles when it conflates investigation with prosecution. Carpio-Morales v. Binay clearly says the Ombudsman can investigate without prosecuting, preserving evidence for post-tenure justice. The post ignores this, peddling despair instead of hope. It also overreaches on the DOJ, claiming it can’t investigate because prosecution might “indirectly” remove Duterte. Hogwash. The DOJ, under Executive Order No. 292 (Administrative Code of 1987), can probe criminal acts without imposing administrative sanctions. The “indirect removal” doctrine from Funa v. Villar (G.R. No. 192791, 2012) isn’t a blanket ban—it’s about preventing actual ouster, not fact-finding.

The post’s claim that the DOJ can freely probe non-impeachable officials (e.g., Senators Chiz Escudero, Joel Villanueva, or Speaker Martin Romualdez) is correct but half-baked. Political realities—like Senate pushback—make DOJ action trickier than the post admits.

C. The Post’s Sin: Surrendering to Impunity

The post‘s biggest crime is its shrugging acceptance of this mess. “Don’t burden Remulla with unrealistic expectations”? Really? So, the rule of law takes a six-year coffee break while ₱500 million in public funds plays hide-and-seek? This isn’t legal analysis—it’s a white flag waved at a system rigged to protect the elite.

IV. The Stakes: Why This Circus Should Make You Furious

A. The ₱500 Million Black Hole

If Remulla and the DOJ can’t act until 2028 (or an impeachment miraculously succeeds), what happens to the ₱500 million in confidential funds? Evidence rots, witnesses vanish, and paper trails turn to dust. Carpio-Morales v. Binay offers a lifeline—fact-finding now, prosecution later—but the post‘s defeatism risks discouraging action, letting public funds slip into oblivion.

B. Impeachment: A Political Clown Car

Impeachment as the only remedy is a sick joke. Congress, a den of political wolves, can bury complaints or wield them as weapons. The alleged dismissal of Duterte’s impeachment case proves it: accountability hinges on the whims of the powerful, not the strength of evidence. This isn’t justice—it’s a reality show with no winners.

C. The Chilling Effect: Impunity’s Cold Embrace

When the public sees Duterte shielded by legal acrobatics, it breeds cynicism. Why blow the whistle if the Ombudsman’s a paper tiger and the DOJ’s too scared to bark? This perception cripples agencies like the Commission on Audit (COA) or Civil Service Commission (CSC), which need public trust to function. The post’s “realistic expectations” are a death knell for accountability.

V. The Verdict: A System Built for Evasion

The Facebook post is a legal half-truth dressed in defeatist drag. It’s right that R.A. 6770 and the Constitution clip Remulla’s wings, and the DOJ’s role is a legal gray zone. But it’s wrong to say nothing can be done. The Ombudsman can investigate to preserve evidence, and the DOJ could probe without stepping on impeachment’s toes. The real scandal? A system that delays justice until the public forgets or the evidence fades, all while preaching “public trust.”

VI. The Battle Plan: Escaping the Constitutional Funhouse

This circus needs to end. Here’s how:

- Legislative Surgery: Congress must amend R.A. 6770 to clarify the Ombudsman’s and DOJ’s investigative powers, allowing fact-finding without fear of “indirect removal” challenges.

- Ombudsman’s Gambit: Remulla should use Carpio-Morales v. Binay to launch a public fact-finding probe into Duterte’s funds. No sanctions, just transparency to keep the heat on.

- Supreme Court Showdown: The Court must reconcile this accountability gap with Article XI’s “public trust” doctrine. A test case on DOJ jurisdiction could end the ambiguity.

- People’s Uprising: Citizens must demand action, not just from Duterte but from a Congress that plays impeachment like a poker game. Media and civil society must keep the ₱500 million in the spotlight.

VII. The Final Sting: No More Excuses

The law may tie Remulla’s hands, but it doesn’t blind his eyes or silence his voice. The Facebook post, while legally sharp in spots, sells us a narrative of impotence we must reject. The ₱500 million isn’t just money—it’s a test of whether the Philippines can hold its elite accountable or whether the powerful get a permanent VIP pass. The Constitution demands trust; it’s time the system delivers. Until then, the Kweba ni Barok will keep slicing through the lies, pen sharp and patience thinner than a politician’s promise. Who’s next in this legal clown show?

Key Citations

- Wilfredo Garrido. “CAN THE NEW OMBUDSMAN REMULLA RUN AFTER THE VICE PRESIDENT?” Facebook, 8 Oct. 2025, https://www.facebook.com/share/p/17CakotYgT/

- Carpio-Morales v. Court of Appeals and Jejomar Binay. G.R. No. 217126-27, 10 Nov. 2015.

- Estrada v. Desierto. G.R. Nos. 146710-15, 2 Mar. 2001.

- Funa v. Villar. G.R. No. 192791, 6 Dec. 2011.

- In Re: Gonzales v. Chavez. G.R. No. 97351, 19 Aug. 1992.

- Republic Act No. 6713. Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees, 20 Feb. 1989.

- Republic Act No. 6770. The Ombudsman Act of 1989, 17 Nov. 1989.

- The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines. Art. XI.

- Executive Order No. 292. Administrative Code of 1987, 25 July 1987.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

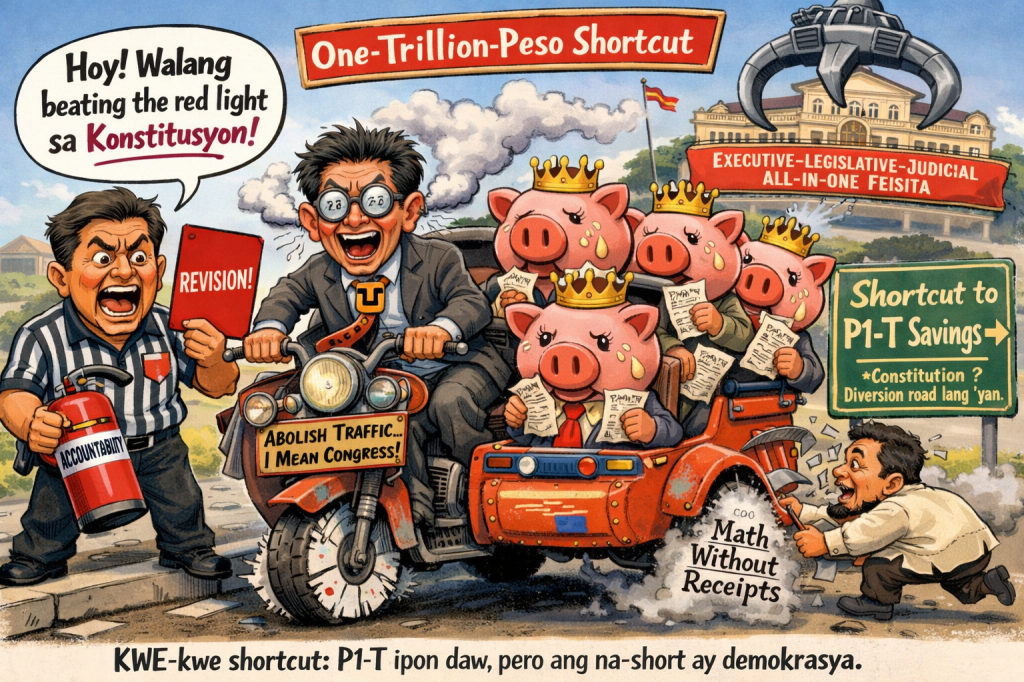

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment