Gordon’s Fiery Nudging: Lighting Remulla’s Path or Fanning a Feud’s Embers?

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — October 12, 2025

MGA ka-kweba, gather your lanterns—newly appointed Ombudsman Jesus Crispin “Boying” Remulla is shining a light on the Pharmally scandal, that lingering shadow of former President Rodrigo Duterte’s pandemic response. With P11.5 billion in contracts awarded to a company barely worth a corner store’s inventory, Remulla’s pledge to “revisit” this “forgotten” case feels like either a heartfelt push for accountability or a carefully timed move in the Marcos-Duterte chess game. Let’s peel back the layers, navigate the legal maze, and discern whether this is a genuine pursuit of truth or a political maneuver dressed in Ombudsman garb.

Remulla’s Spotlight: A Quest for Truth or a Calculated Move?

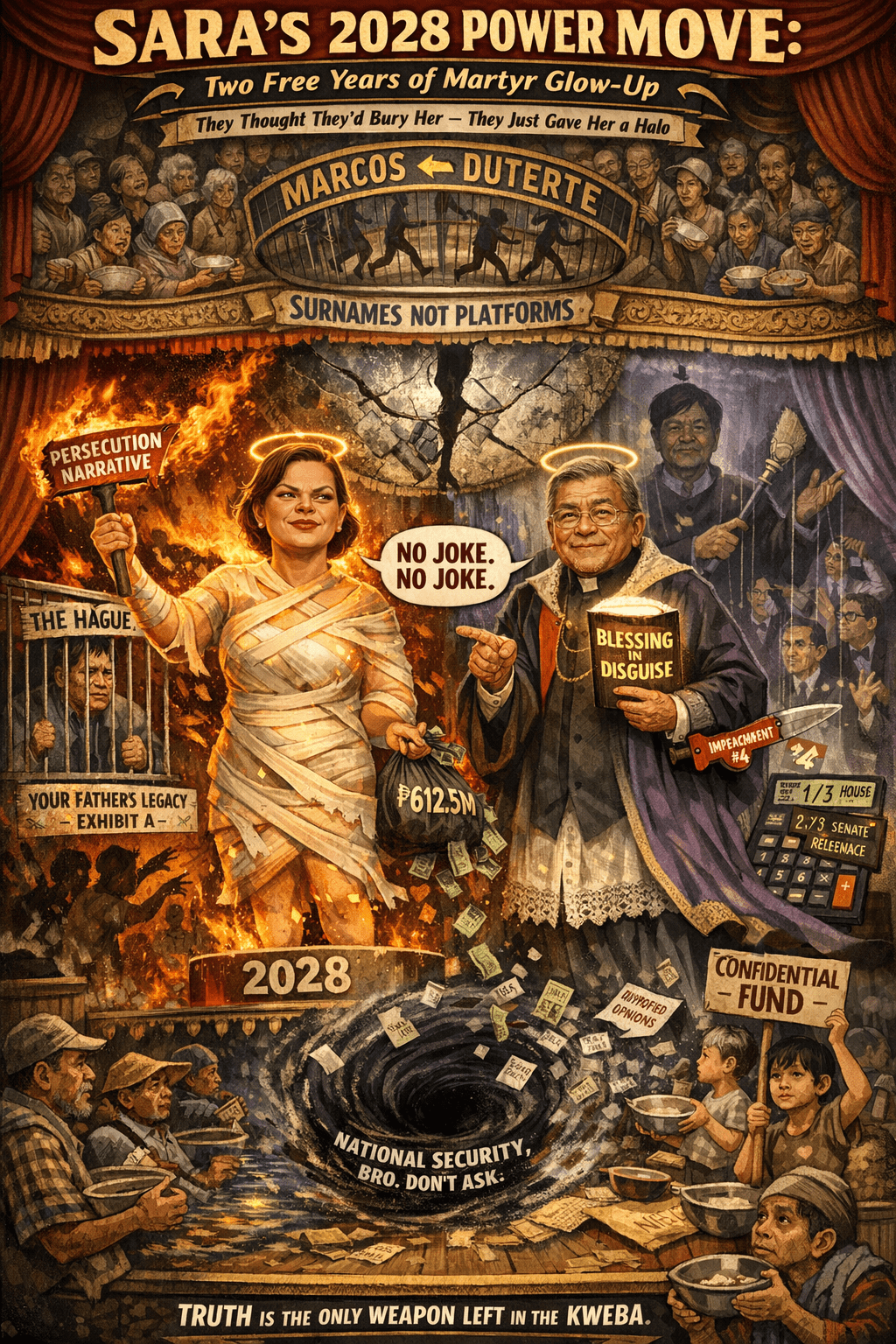

Sworn in as Ombudsman on October 9, 2025, Remulla opened with a bold promise: to dust off the Pharmally Pharmaceutical Corporation case, insisting it’s “buried in oblivion” yet carries “weight.” It’s a compelling narrative, but the timing—amid the unraveling of the Marcos-Duterte UniTeam—raises eyebrows. The Pharmally scandal, with its P11.5 billion in contracts to a firm with just P625,000 in capital, has been a public sore spot since the Senate Blue Ribbon Committee probe (2021-2022). Is Remulla genuinely reviving a stalled pursuit, or is this a strategic play?

Arguments for Remulla’s Initiative

Remulla’s focus aligns with the Ombudsman’s mandate under Republic Act (RA) No. 6770, the Ombudsman Act of 1989, to investigate graft and uphold ethical governance. The Senate’s findings—overpriced Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) test kits, Pharmally’s questionable qualifications, and links to Duterte’s adviser Michael Yang—demand scrutiny. Public sentiment on X, with calls to “ikulong ang sangkot” (jail the involved), supports this, as does Acting Chief Justice Marvic Leonen’s urging for “strategic cases” to drive reform. Ongoing graft charges against Lloyd Lao and Francisco Duque provide a foundation; Remulla could leverage these to pursue broader accountability under RA 3019, the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act.

Arguments Against: Questions of Timing

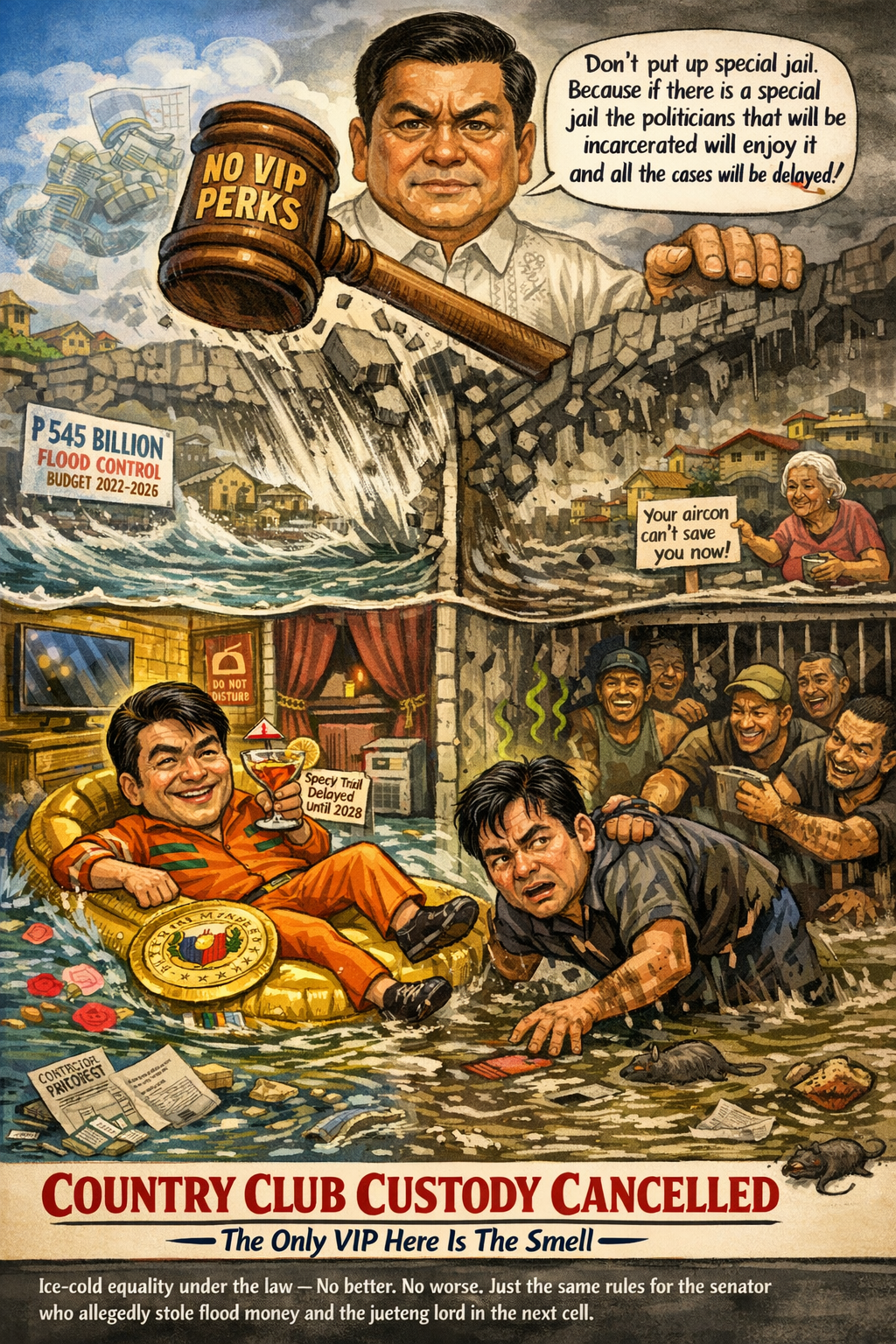

Remulla’s past as Department of Justice (DOJ) Secretary under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. invites questions about impartiality. The Pharmally case isn’t exactly “forgotten”—graft cases are active in the Sandiganbayan, and Procurement Service-Department of Budget and Management (PS-DBM) officials faced administrative sanctions in 2023. The Marcos-Duterte rift, with 2028 elections on the horizon, suggests this revival could amplify Marcos’s anti-corruption image while casting a shadow on Duterte’s legacy. Some X users note Remulla’s focus sidesteps newer issues, like Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) graft. His dual emphasis on DPWH suggests a broader agenda, but risks delays due to resource constraints, as cautioned against in People v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. No. 169004, 2010) regarding inordinate delays violating speedy disposition rights. Still, RA 6713, the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees, supports his duty to act transparently.

The DPWH Subplot: Broadening the Lens?

Remulla’s attention to DPWH “emergencies” alongside Pharmally hints at a wider anti-corruption push. DPWH’s current issues, less tied to Duterte, offer a less contentious target, allowing Remulla to demonstrate commitment without diving fully into Pharmally’s political waters. However, juggling both risks delays, as People v. Sandiganbayan warns against prolonged prosecutions.

Verdict on Remulla: His legal mandate to probe is clear, but the political context demands careful navigation. With robust evidence and transparent processes, Remulla can turn this spotlight into meaningful accountability. Without it, the glow risks fading into political theater.

Gordon’s Rallying Cry: Watchdog’s Bark or Echoes of Old Rivalries?

Former Senator Richard “Dick” Gordon, who led the Blue Ribbon probe, is back in 2025, urging Remulla to pursue Pharmally and pointing to Duterte as part of a “conspiracy to fleece” P11-47 billion. His call, labeling it the “corruption of the century,” is classic Gordon—passionate and resolute. Is he a steadfast advocate for justice or a figure shaped by past tensions?

Gordon as Accountability Advocate

Gordon’s probe uncovered critical evidence: Pharmally’s meager capital, overpriced kits (e.g., P600M for 8,000 RT-PCR kits), and Michael Yang’s influence. His draft report, though unadopted in 2022, recommended charges, and his 2025 push keeps the issue alive. Senate referrals to the Anti-Money Laundering Council (AMLC) and testimony on irregular approvals strengthen his case. Gordon’s history—Red Cross leadership, anti-graft advocacy—positions him as a consistent voice for reform, aligned with RA 6713’s ethical standards. My friends in various social media platforms praise his persistence, seeing it as a call for systemic change.

Gordon’s Challenges: Shadows of Past Conflicts

Gordon’s 2021 disputes with Duterte—over Red Cross funds and a Commission on Audit (COA) audit on Subic Bay Metropolitan Authority (SBMA)—raise questions about neutrality. His conspiracy claim, while striking, relies on Senate testimony that’s more suggestive than conclusive. Duterte supporters on X highlight the Senate Blue Ribbon Committee’s 2022 draft report, which failed to secure sufficient signatures for adoption before the 18th Congress adjourned, as evidence of the Pharmally investigation’s limited momentum and impact. Ombudsman v. Bongais (G.R. No. 226405, 2018) supports investigative freedom, but Gordon’s accusations need concrete evidence to translate into legal action. Past tensions don’t negate his findings, but they complicate perceptions.

Verdict on Gordon: His probe provided a vital roadmap, but his Duterte conspiracy charge needs stronger evidence to move from rhetoric to courtroom. Gordon’s advocacy is commendable, but its impact hinges on new proof to back his bold claims.

Navigating the Legal Maze: Prosecuting Pharmally Without Tripping

The Ombudsman’s toolkit—RA 3019, RA 7080 (Anti-Plunder Act), and Revised Penal Code (RPC) malversation—offers paths to hold Pharmally’s players accountable, but each comes with hurdles. Let’s chart the routes and pitfalls.

Promising Pathways

- Graft (RA 3019, Section 3(e)): The most solid option. Charges against Lao and Duque for P41 billion Department of Health (DOH)-PS-DBM transfers are progressing. Evidence includes irregular contract awards, overpricing, and Pharmally’s unfit status. Penalties: 1-10 years, disqualification. The Sandiganbayan’s jurisdiction (RA 10660, cases >P1M) is confirmed, as shown in its 2024 ruling. Precedent: SC Upholds Conviction of Iloilo Supplier (G.R. No. 251693, 2024) supports graft for procurement fraud.

- Malversation (RPC Art. 217): Effective against accountable officers (e.g., Lao) for misusing funds. Evidence: COA audits showing unaccounted funds or substandard deliveries. Penalty: Up to 7 years, fines. Regional Trial Courts (RTCs) handle cases without high-ranking officials.

- Civil Forfeiture (RA 7080, Section 2): Recover ill-gotten wealth via Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG)/DOJ, non-prescriptive. AMLC’s bank probes can trace proceeds.

- Administrative Sanctions (RA 6713): Dismissal, benefit forfeiture for misconduct, as applied in 2023 against Lao et al. Precedent: Ombudsman v. Gahutan (G.R. No. 164679, July 27, 2011).

Riskier Pathways

- Plunder (RA 7080): Requires P50M+ ill-gotten wealth and a “pattern.” The Ombudsman’s 2023 no-plunder ruling cited insufficient pattern evidence. Gordon’s P47B estimate needs AMLC-traced proceeds or multiple acts to hold. People v. Dela Piedra (G.R. No. 121777, January 24, 2001) demands a clear series, a high bar.

- Estafa/Perjury (RPC): Against private actors (Pharmally executives) for fraud or false testimony. Proving intent is challenging without insider witnesses.

Evidentiary Hurdles

- Graft: Requires “manifest partiality” or “undue injury.” Senate testimony (e.g., Yang’s role) risks hearsay; bank records or signed waivers are essential. Weakness: Lack of direct orders from senior officials.

- Plunder: Needs wealth accumulation and pattern. Fragile without AMLC-traced proceeds or corroborated acts.

- Malversation: Strong with COA audits, but weaker if deliveries occurred, even if substandard.

Procedural Pitfalls

- Prescription: RA 10910 extends RA 3019 to 15 years, plunder to 20 (RA 7080, Section 6). 2020-2021 contracts are within limits, but delays risk People v. Sandiganbayan objections.

- Jurisdiction: Sandiganbayan covers high officials/losses >P1M (RA 10660). Errors invite certiorari, as in Ombudsman v. Morales (G.R. No. 208496, 2017).

- Senate Evidence: Hearsay risks exclusion (People v. Gimenez, G.R. No. 174737, 11 January 2016.). The Ombudsman must re-validate via AMLC/COA.

- Selective Prosecution: Defense may claim bias, invoking People v. Dela Piedra on impartiality.

Verdict on Pathways: Graft and administrative sanctions offer the clearest shot, with Sandiganbayan momentum. Plunder requires stronger evidence. Remulla must fortify filings to avoid procedural snags.

The Duterte Puzzle: Can They Pin the Former Kingpin?

Pursuing a former president is like threading a needle in a storm. Gordon’s claim—Duterte orchestrated a P47B heist—grabs attention but lacks legal weight. Let’s assess the odds with clear eyes.

Likelihood and Feasibility

Challenging without concrete evidence. Former presidents lose immunity post-tenure (People v. Dela Piedra), but proving Duterte’s role demands specific, admissible proof: signed orders, communications directing Pharmally’s selection, or bank trails showing personal gain. The Senate’s Yang ties and P41B transfer are suggestive but circumstantial. The Ombudsman’s 2023 no-plunder ruling indicates weak evidence even for mid-level figures. Gordon’s P47B figure is ambitious but unproven.

Required Evidence

- Direct orders (memos, emails) linking Duterte to Pharmally’s selection or transfers.

- AMLC-traced proceeds to Duterte or proxies.

- Corroborated testimony from insiders (e.g., Lao) on explicit instructions.

- Authenticated procurement waivers signed by Duterte’s office.

Without these, the case falters. Senate testimony lacks the precision courts require (People v. Gimenez).

Consequences of Pursuit

- Political: Charging Duterte could deepen the Marcos-Duterte divide, risking coalition fractures. X posts show Duterte supporters decrying “vendetta.” Success could bolster Marcos’s reformist image; failure fuels skepticism.

- Legal: Defense will file certiorari petitions, citing Ombudsman v. Morales on abuse of discretion. Trials could extend beyond 2028, straining Sandiganbayan.

- Social: Public trust depends on evidence. A weak case risks reinforcing impunity, as X users note with unpunished PhilHealth scandals.

Verdict on Duterte: Charging him is unlikely without a breakthrough. The Ombudsman should focus on achievable cases against figures like Lao, not chase a giant without a spear.

Final Verdict: Shining Light or Casting Shadows?

Remulla’s pledge to revisit Pharmally is legally grounded and publicly resonant. With RA 3019, Sandiganbayan jurisdiction, and AMLC tools, he can pursue procurement violators and recover funds. Graft charges against Lao and Duque are advancing; administrative sanctions are secured. But targeting Duterte remains a long shot without compelling evidence. Gordon’s advocacy adds momentum, but his conspiracy claims need substantiation to move beyond rhetoric.

Remulla’s success hinges on execution. A transparent, evidence-driven approach could restore trust and deliver justice. If clouded by political undertones, it risks becoming a fleeting spotlight. Shine brightly, Ombudsman, or the shadows will linger.

Key Citations

- People v. Dela Piedra, G.R. No. 121777, 24 January 2001.

- Ombudsman v. Bongais, G.R. No. 226405, 25 July 2018.

- Ombudsman v. Gahutan, G.R. No. 164679, 27 July 2011.

- “SC Upholds Conviction of Iloilo Medical Supplier for Graft.” Supreme Court of the Philippines. Accessed 12 Oct. 2025.

- Ombudsman v. Quimbo, G.R. No. 173277, 25 Dec. 2008.

- People v. Sandiganbayan, G.R. No. 169004, 16 Sep. 2010.

- People v. Gimenez, G.R. No. 174737, 11 January 2016.

- Ombudsman v. Morales, G.R. No. 208496, 25 July 2017.

- Republic Act No. 3019. Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, 17 Aug. 1960.

- Republic Act No. 6770. Ombudsman Act of 1989, 17 Nov. 1989.

- Republic Act No. 7080. Anti-Plunder Act, 12 July 1991.

- Republic Act No. 10660. An Act Strengthening the Functional and Structural Organization of the Sandiganbayan, 16 Apr. 2015.

- Republic Act No. 10910. An Act Increasing the Prescriptive Period for Violations of Republic Act No. 3019, 21 July 2016.

- Sarao, Zacarian. “Ombudsman Remulla to Revisit Pharmally Corruption Scandal.” Inquirer.net, 9 Oct. 2025.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment