Navigating the Flood of Graft: Remulla’s Sink-or-Swim Judicial Overhaul

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — October 13, 2025

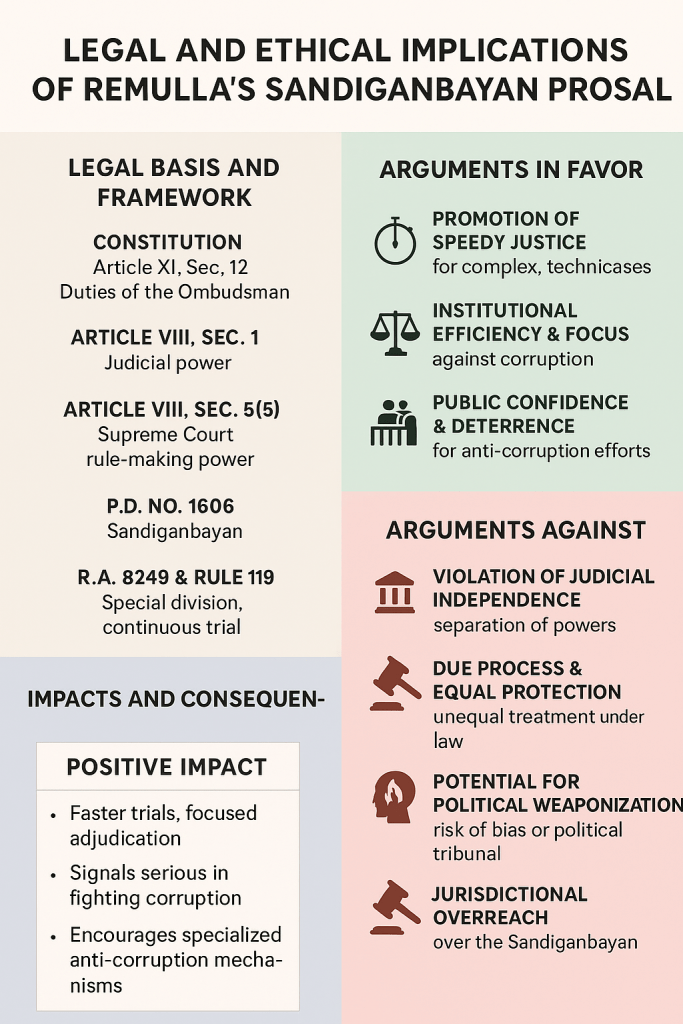

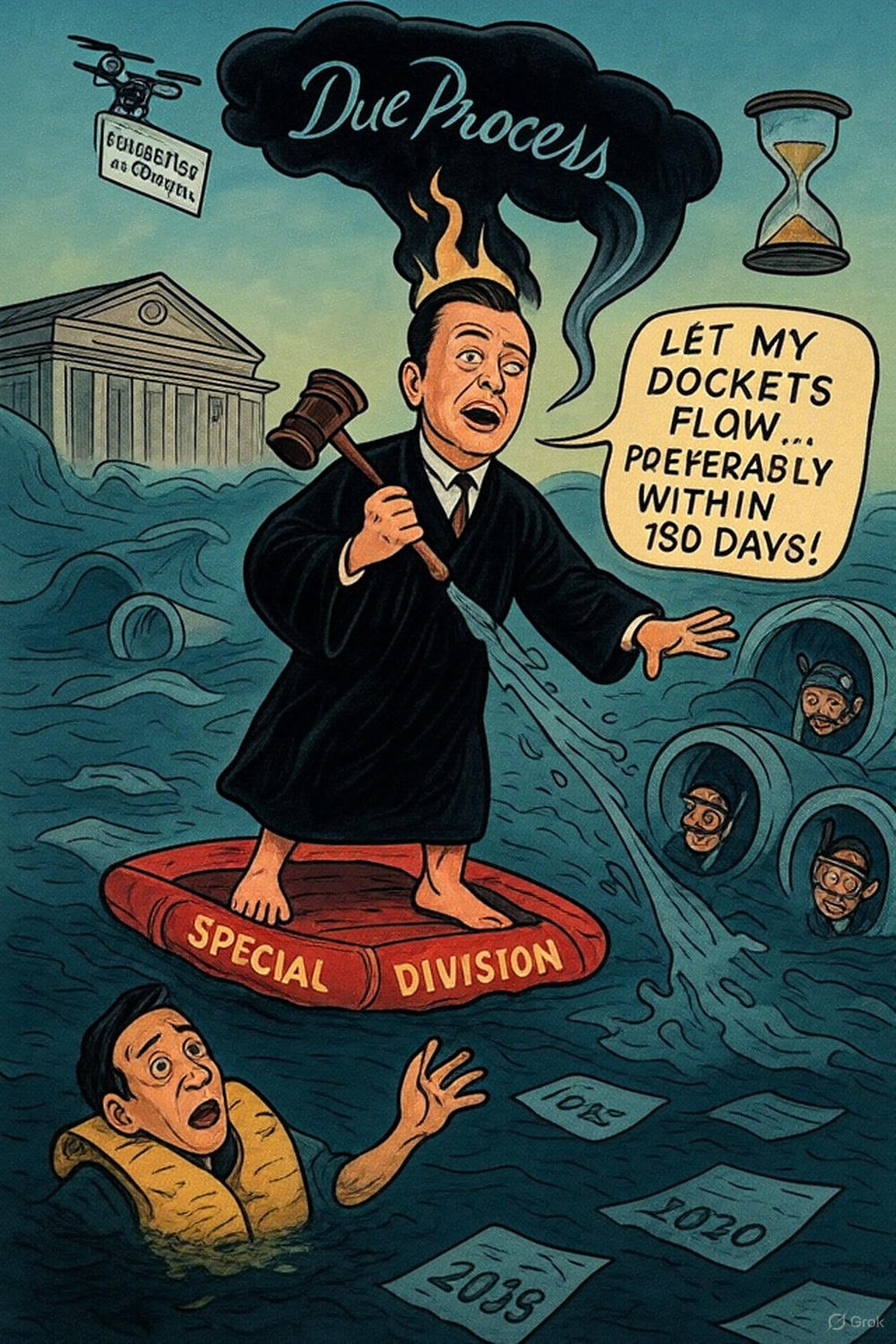

THE Philippines, a nation battered by typhoons and betrayed by corruption, watches flood control funds vanish into ghost projects while communities wade through misery. The Sandiganbayan, our anti-graft court, is a judicial quagmire, its dockets a graveyard where plunderers rest easy as cases crawl slower than a flooded jeepney. Enter Ombudsman Jesus Crispin Remulla, brandishing a plan for a special Sandiganbayan division to fast-track flood control cases. Is this a lifeline for justice or a mirage in the deluge? With a legal scalpel and a tongue sharp enough to cut through bureaucratic hogwash, let’s shred this proposal to see if it holds water or sinks under its own hubris.

Remulla’s Grand Splash: Genius or Gimmick?

Ombudsman Remulla’s plan is a four-pronged plunge into the murky waters of Philippine justice. First, he proposes a special Sandiganbayan division to tackle flood control anomalies, targeting Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) engineers, contractors like Cezarah “Sarah” Discaya, and big-name politicians. Second, he demands continuous trials, a blitz to bypass the court’s glacial pace. Third, he vows to file only “trial-ready” cases, aiming to avoid the Ombudsman’s legacy of flimsy indictments. Finally, he’ll selectively adopt National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) recommendations, prioritizing charges against figures like Senators Francis Escudero and Nancy Binay based on “gravity” and speed. Is this a bold stroke to drain the swamp or a reckless dive into constitutional quicksand? Let’s wade in.

The Judicial Maelstrom: Slicing Through Remulla’s Plan with Savage Precision

A Special Division: Lifeline for Justice or Constitutional Mutiny?

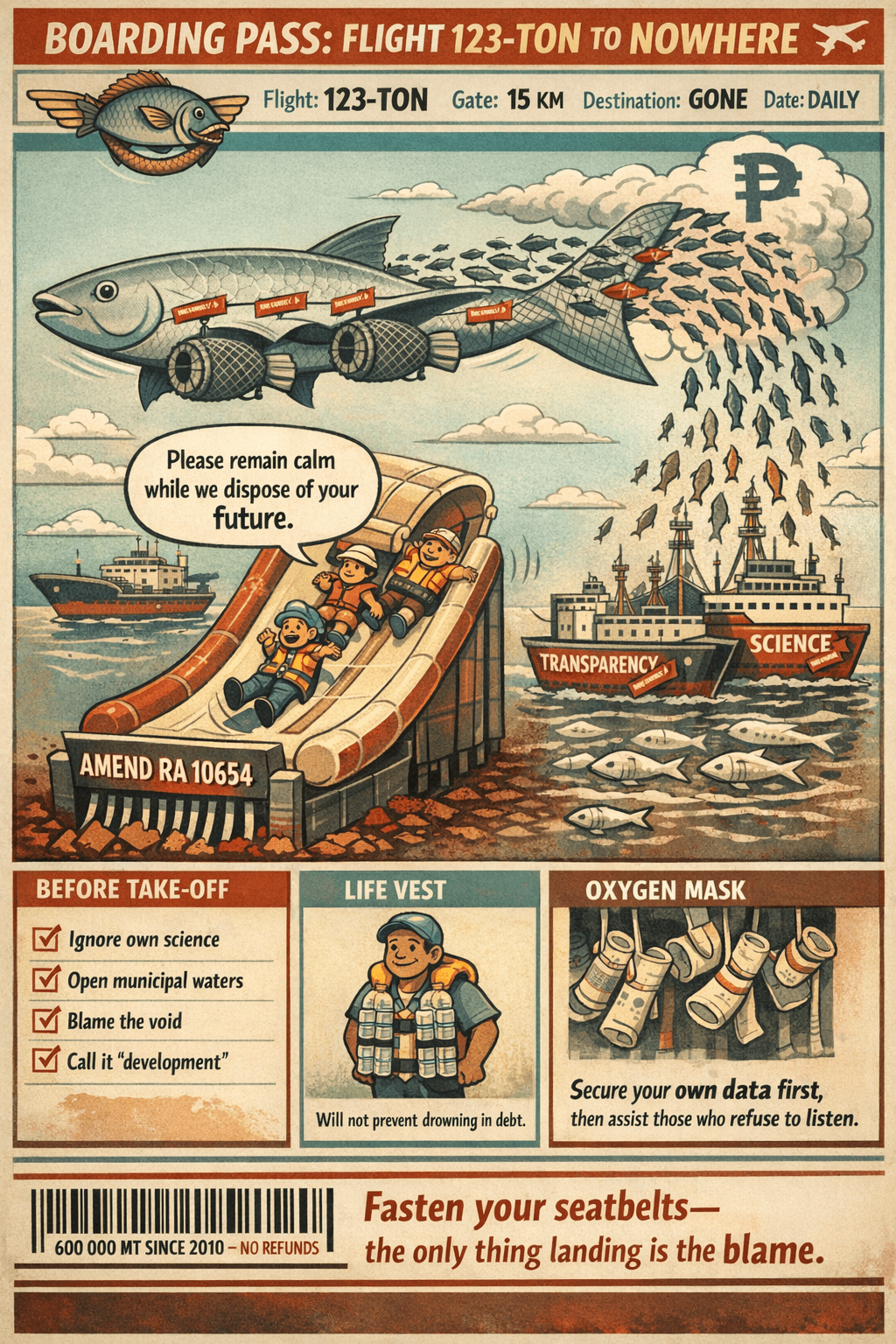

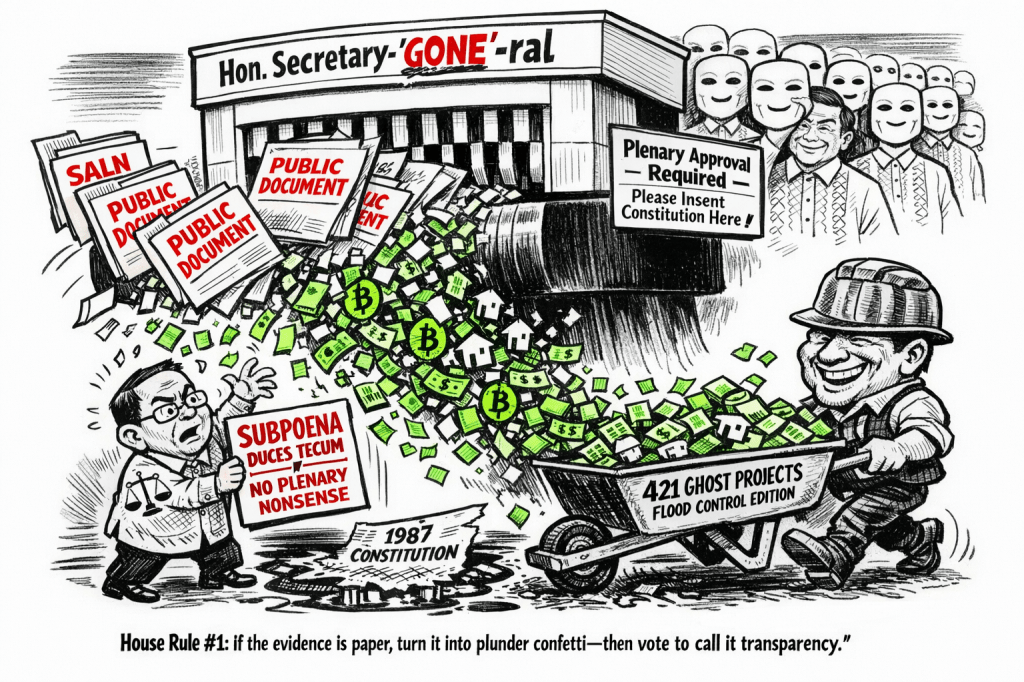

The Case For: A dedicated division is no mere whim—it’s a desperate antidote to a system drowning in corruption. Flood control scams, with 421 of 8,000 projects flagged as ghosts, leave Filipinos submerged during typhoons like Ondoy or Yolanda, costing lives and billions. The 1987 Constitution’s Article III, Section 16 guarantees a speedy trial, and Article XI, Section 12 mandates the Ombudsman to “act promptly.” The Speedy Trial Act of 1998 (Republic Act No. 8493) demands trials conclude within 180 days, yet Sandiganbayan cases languish for 5–10 years. Precedents like the Supreme Court’s Continuous Trial Guidelines (A.M. No. 15-06-10-SC) and the Sandiganbayan’s Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF) division show specialization can streamline complex cases, mastering evidence like falsified DPWH contracts. This could be the lifeboat typhoon victims need. Corpuz v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. No. 162214, November 11, 2004). emphasizes balancing the right to speedy trial with the state’s interest in prosecuting corruption, noting that undue delays violate the accused’s rights but also harm public interest by allowing corrupt officials to evade accountability. This could be the lifeboat typhoon victims need.

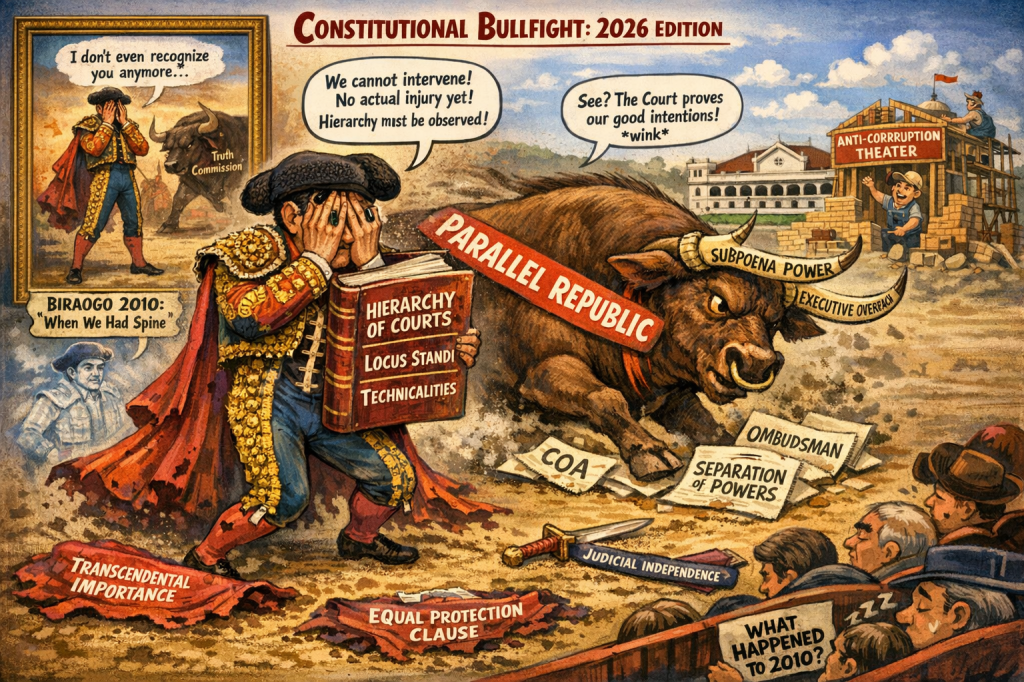

The Case Against: But don’t break out the champagne—this reeks of executive overreach. The Sandiganbayan falls under the Supreme Court’s sole authority (Article VIII, Section 5), and Remulla, an Ombudsman with prosecutorial powers, can’t dictate judicial structure. In Pimentel v. Aguirre (G.R. No. 132988, 19 July 2000), the Supreme Court smacked down executive meddling in other branches’ turf, and Remulla’s treading dangerously close. A special division risks becoming a political guillotine, especially with names like Escudero and Binay in the dock. Why them? Why now? Estrada v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. No. 148560, 19 November 2001) warned against procedural bias, and this smells like a star chamber. Diverting judges to Remulla’s pet project could starve other cases, breaching the equal protection clause (Article III, Section 1). This isn’t reform; it’s a constitutional shipwreck waiting to happen.

Continuous Trials: Rocket to Justice or Crash Landing?

The Case For: Continuous trials are a legal godsend in a system where justice moves slower than a Manila flood. The Supreme Court’s Continuous Trial Guidelines and Republic Act No. 8493 mandate swift hearings, critical for flood control cases with their tangled webs of graft and falsification. Every delay lets crooks dodge accountability while typhoon victims drown in despair. Remulla’s push aligns with the Ombudsman Act of 1989 (Republic Act No. 6770), urging efficient prosecution. Global anti-corruption courts show continuous trials deter graft by signaling swift punishment, a lesson the Philippines desperately needs.

The Case Against: Speed is alluring, but haste courts disaster. Rushing trials risks trampling the defense’s right to prepare, especially in complex cases under Revised Penal Code (RPC) Articles 171–172 (falsification) or Article 217 (malversation). The Constitution’s Article III, Section 14(2) guarantees an impartial trial, and People v. Moreno (G.R. No. 261857, 28 October 2024) dismissed cases for rushed proceedings that botched due process. The Sandiganbayan’s already stretched thin—where are the extra judges or courtrooms? Remulla’s betting on a system too waterlogged to deliver, risking acquittals or overturned convictions in a mad dash for headlines.

Trial-Ready Cases: Surgical Precision or Selective Slaughter?

The Case For: Filing only “trial-ready” cases is a middle finger to the Ombudsman’s history of sloppy indictments. The Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees (Republic Act No. 6713) demands “utmost responsibility,” and weak filings clog dockets while letting crooks walk. Under the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act (Republic Act No. 3019), convictions require ironclad evidence of “manifest partiality” or “undue injury.” The DPWH’s charges show forensic audits can pin down culprits—if the Ombudsman does its homework. This could rebuild trust in a system where acquittals often stem from prosecutorial incompetence.

The Case Against: Sounds great, but this smells like a pretext for cherry-picking. Who decides “trial-ready”? Remulla’s discretion risks prioritizing high-profile scalps while ignoring smaller but equally vile scams. People v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. No. 169004, 15 September 2010) upheld the Ombudsman’s leeway but warned against arbitrariness. Focusing on Discaya or Revilla while sidelining lesser-known contractors screams political theater. Building “trial-ready” cases takes time—audits, witnesses, evidence preservation. In a country where whistleblowers vanish, this could mean more delays, not fewer, for “less grave” cases.

Selective NBI Picks: Strategic Triage or Political Hit List?

The Case For: Prioritizing grave cases is smart resource allocation. Republic Act No. 6770 lets the Ombudsman focus on high-impact crimes, like ghost projects costing billions and endangering lives. The NBI’s recommendations—graft, malversation, bribery—target systemic rot in DPWH’s Bulacan office. Quick convictions under Republic Act No. 3019 could deter future scams, aligning with its goal of punishing “undue injury.” This is triage in a justice system stretched to breaking.

The Case Against: Selective prosecution is a slippery slope to a kangaroo court. Naming senators like Escudero and Binay while sparing others screams bias—Gonzales v. Chavez (G.R. No. 97351, 25 February 1992) warned the Ombudsman against even the appearance of favoritism. What’s “grave” about one ghost project over another when both kill during floods? This selectivity flouts Republic Act No. 6713‘s call for “justness and sincerity,” turning Remulla into a political sniper rather than a impartial prosecutor.

The Eternal Swamp of Slow Justice: A System Submerged

The Sandiganbayan’s track record is a legal tragedy written in sludge. Estrada’s plunder case took seven years; PDAF scams, a decade. The World Justice Project ranks the Philippines dismally for judicial delays, with corruption cases averaging 5–10 years. This isn’t justice; it’s a mockery where dockets drift like debris in a flooded barangay. Remulla’s urgency is a flare in the dark, but can he navigate a court understaffed, underfunded, and overwhelmed? His proposal risks building a shiny new raft on a sinking ship, with justice still stuck in the mud.

The Final Gavel: A Bold but Flawed Plunge into Reform

Remulla’s proposal is a high-stakes dive into a broken system. The intent—to punish those who profit while floods devastate—is noble. The execution, however, teeters on constitutional peril, risking judicial independence and due process for a shot at quick wins. Is it necessary? Absolutely. Flawed? Undeniably. The Sandiganbayan’s inertia demands a shock, but not one that capsizes the separation of powers.

The Path Forward:

- Scrap the Special Division: It’s a constitutional non-starter. Instead, petition the Supreme Court for preferential and continuous trial of flood control cases under Continuous Trial Guidelines (A.M. No. 15-06-10-SC), respecting judicial authority.

- Form an Ombudsman Task Force: Build “trial-ready” cases internally, leveraging forensic audits and whistleblower protections without meddling in Sandiganbayan structure.

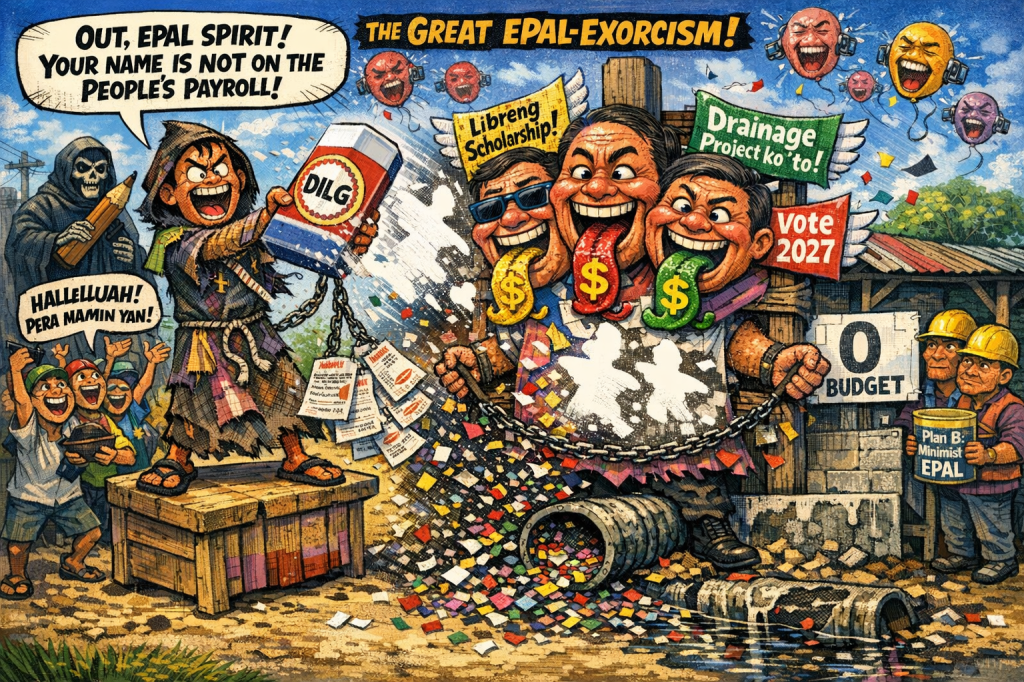

- Demand Transparency: Publish clear criteria for case selection—gravity, evidence, impact—to quash accusations of bias.

- Stay Above Politics: Avoid targeting high-profile names for clout. Prosecute without fear or favor, per Republic Act No. 6770.

Will Remulla’s crusade clear the floodwaters of corruption, or will it sink in legal quicksand? The public watches, wading through the wreckage of broken promises. Justice can’t afford to drown again.

Key Citations

- Corpuz v. Sandiganbayan. G.R. No. 162214, 11 November 2004.

- Estrada v. Sandiganbayan. G.R. No. 148560, 19 November 2001.

- Gonzales v. Chavez. G.R. No. 97351, 25 February 1992.

- Magno v. People. G.R. No. 230657, 14 November 2018.

- Ocampo v. Abando. G.R. No. 176830, 11 February 2014.

- Pimentel v. Aguirre. G.R. No. 132988, 19 July 2000.

- People v. Moreno. G.R. No. 261857, 28 October 2024.

- People v. Sandiganbayan. G.R. No. 169004, 15 September 2011.

- Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 1987 Constitution. Official Gazette, 1987.

- Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. “Act No. 3815, S. 1930.” Official Gazette, Republic of the Philippines, 8 Dec. 1930. Accessed 12 Oct. 2025.

- Republic Act No. 3019: Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. 17 August 1960.

- Republic Act No. 6713: Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees. 20 February 1989.

- Republic Act No. 6770: The Ombudsman Act of 1989. 25 July 1989.

- Republic Act No. 8493: Speedy Trial Act of 1998. 12 February 1998.

- Reyes, Dempsey. “Remulla Wants Special Division in Sandigan to Try Flood Cases.” Inquirer.net, 11 October 2025.

- Supreme Court of the Philippines. Revised Guidelines for Continuous Trial of Criminal Cases (A.M. No. 15-06-10-SC). 25 April 2017.

- World Justice Project. Rule of Law Index, 2024.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

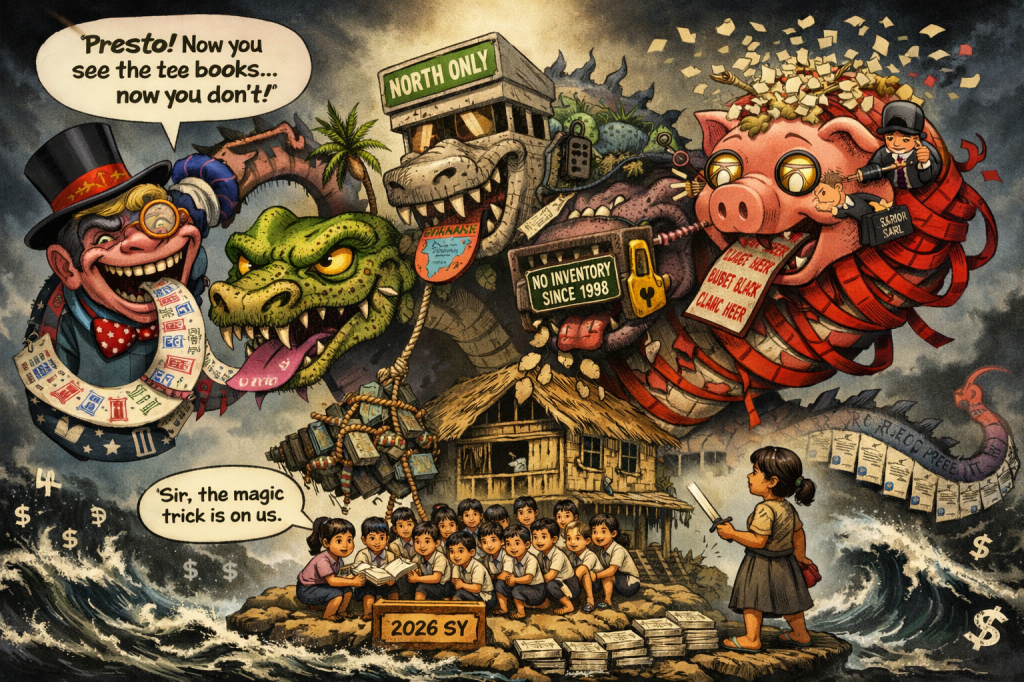

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment