Manpower Myths and Ghostly Graft: Dismantling COA’s Drowning Defenses

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — October 16, 2025

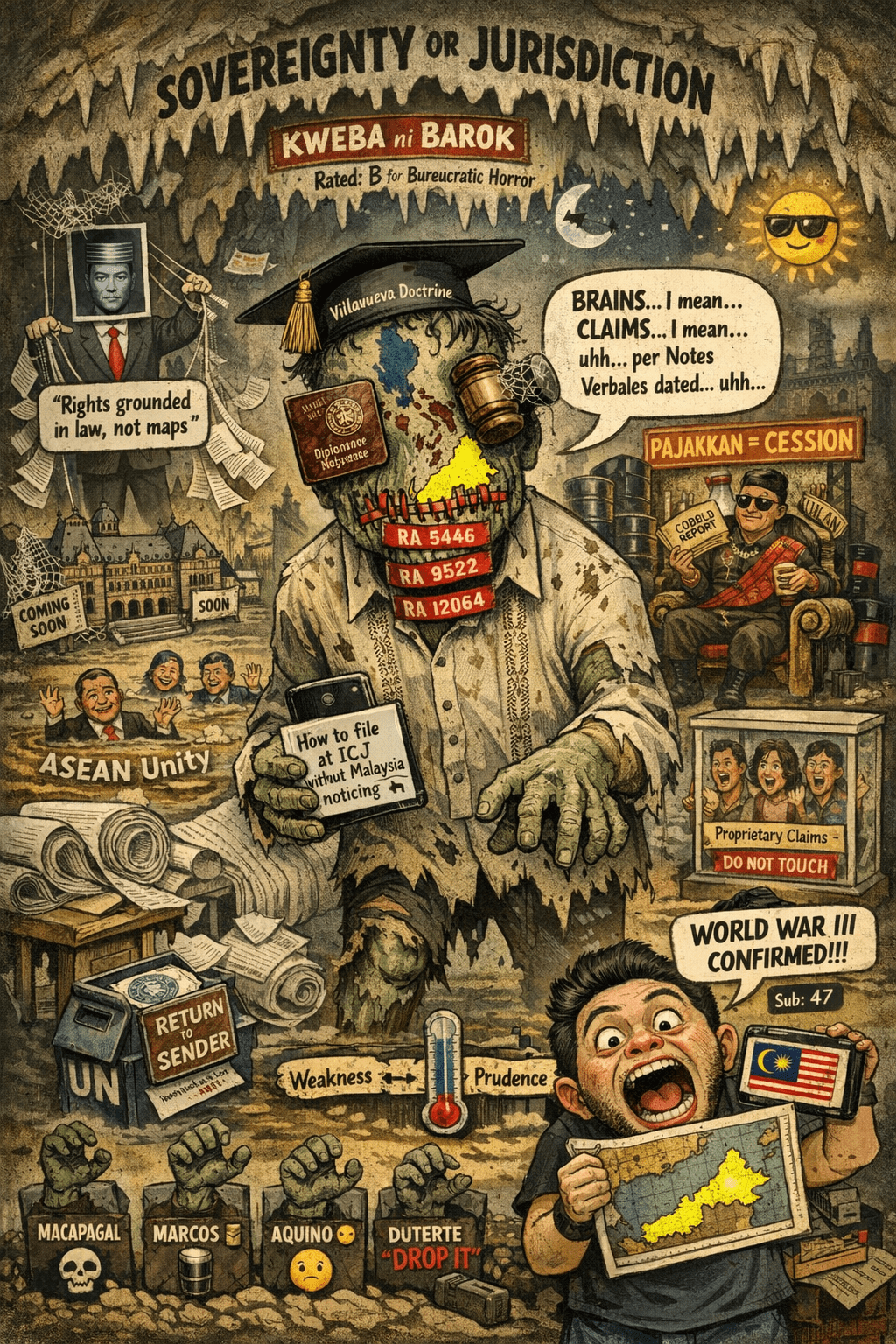

Dear readers of Kweba ni Barok,

In the sodden aftermath of yet another typhoon season, where Filipinos wade through knee-deep floods in their living rooms, a scandal has burst forth like a breached dike: billions of pesos meant for flood control vanishing into “ghost projects” and shoddy constructions that crumble faster than political promises. At the heart of this deluge stands the Commission on Audit (COA), our supposed guardian of the public purse, now pleading poverty in personnel. Chair Gamaliel Cordoba, in a Senate hearing on October 13, 2025, blamed a “lack of manpower” for failing to flag these anomalies earlier—pointing to just two auditors covering Bulacan’s 1st District Engineering Office (DEO), the “epicenter” where nearly half of Region 3’s flood funds (20% of the national total) were squandered.

It’s a defense that sounds almost reasonable, until you realize it’s the audacity of austerity: an agency tasked with watching trillions excusing its blindness because the budget cutters clipped its eyes. As someone who’s spent years dissecting the rot in our power structures, I see this not as a mere oversight but a profound betrayal—a test of whether the Philippines’ accountability ecosystem is a sturdy levee or just another porous embankment waiting to fail the next storm. Let’s dissect this, fact by fact, outrage by measured outrage, because the real flood here is one of impunity.

The “Manpower” Misdirection: An Excuse Drowning in Its Own Logic

Cordoba’s argument hinges on cold numbers. In Bulacan’s 1st DEO—spanning 11 municipalities and three cities, overseeing projects worth tens of billions—COA had only a team leader and an assistant. This, he said, stemmed from Department of Budget and Management (DBM) cuts that slashed 963 positions agency-wide, leaving auditors stretched like overextended flood barriers. Evidence backs the strain: flood control allocations ballooned to P545 billion nationally, with Bulacan cornering a disproportionate share through repeat contractors like the Discayas family, who allegedly pocketed P31 billion. In such a concentration of funds, two auditors couldn’t possibly verify every geotagged photo or cross-check invoices without Herculean effort.

Fair enough—on paper. Resource constraints are real; COA’s own data shows workload per auditor skyrocketing, and global auditing standards acknowledge that staffing shortages can delay detections. Cordoba even highlighted proactive steps: 21 fraud audit reports issued, eight referred to the Office of the Ombudsman, leading to suspensions of Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) engineers like Henry Alcantara and Brice Hernandez.

But here’s where the excuse springs a leak. Even with skeletal staff, why did risk-based auditing—COA’s own touted methodology—fail so spectacularly? Bulacan was a screaming red flag: massive allocations, identical bogus documents recycled across sites, contractors with political ties. Yet audits over years (2022-2025) issued “unqualified opinions,” greenlighting the farce. Technology? In an era of drones and data analytics, COA could have deployed sampling algorithms or cross-matched procurement records remotely, flagging patterns without boots on every muddy ground. Instead, verification lagged until Senate hearings and whistleblowers forced the issue.

This isn’t just understaffing; it’s a convenient shield for deeper failures. If two auditors were overwhelmed, why no urgent reallocations from quieter districts? Why no clarion calls for tech upgrades before the scandal broke? Cordoba’s plea smacks of misdirection, hiding institutional inertia or worse—willful blindness—behind DBM’s budget axe. In a country where floods kill dozens annually, excusing billions lost because “we’re short-handed” is like a lifeguard blaming a lack of swimsuits for drownings.

The Specter of Complicity: Watchdog or Lapdog?

Whispers of COA’s complicity aren’t baseless paranoia; they’re echoed in Senate probes and media exposés. Take Commissioner Mario Lipana, whose spouse owns Olympus Construction, a firm that bagged P505 million in flood projects. Cordoba admitted this conflict in hearings, yet it persisted unchecked, raising the specter of insider capture. Patterns abound: auditors probed for possible bribery, “clean” reports despite duplicated fakes from DPWH’s “factory of documents,” and audits ramping up only post-exposure. Historical echoes—like COA’s role in the pork barrel scam—suggest a culture where red flags wave ignored until the public storms the gates.

For balance, outright complicity isn’t proven. The fraud’s scale—hundreds of projects, political insertions by senators like Jinggoy Estrada—could overwhelm even a robust agency. COA’s mandate focuses on financial compliance, not real-time fraud hunting; primary blame lies with DPWH implementers. And credit where due: Cordoba’s team cooperated with investigations, detaining officials for contempt and pushing referrals. Resource cuts are documented, and self-probes into auditors show a bid for self-correction, not concealment.

Yet, the appearance of lapdog-ism erodes trust. If conflicts fester and priorities falter, COA risks becoming an enabler, not enforcer. This scandal demands forensic scrutiny: Was it mere overload, or a cozy arrangement where oversight blinked at familiar faces?

A Blueprint for Integrity: Reforms COA Must Adopt, Or Perish

Criticism without solutions is just noise in the rain. COA under Cordoba must pivot from excuses to action—categorized here for clarity, lest they drown in vagueness.

Short-Term (Weeks to 3 Months)

- Freeze high-risk projects and deploy rapid task forces for on-site triage in epicenters like Bulacan—publish the list publicly for accountability.

- Mandate immediate conflict disclosures: All officials, including Cordoba, submit family business ties online, with recusal for any links to implicated contractors like Olympus.

- Bolster whistleblower channels with anti-retaliation guarantees, incentivizing DPWH insiders to spill before the next Senate circus.

Medium-Term (3-12 Months)

- Establish a dedicated data analytics unit—using artificial intelligence (AI) to score risks on contractor concentrations and invoice anomalies.

- Pilot third-party verifications: Independent engineers from universities test materials randomly, bypassing potentially compromised auditors.

- Rotate field teams across districts to prevent capture, separating duties between desk reviews and approvals.

Long-Term (12+ Months)

- Push legislative reforms for inter-agency data sharing—real-time access to DPWH payments and Anti-Money Laundering Council (AMLC) traces via memoranda of understanding (MOUs) or new laws.

- Build a public transparency portal: Machine-readable audit trails, contractor blacklists, and findings open to civil society scrutiny.

- Tie COA’s budget restorations to performance metrics, like recovery rates from disallowances, ensuring funds flow to integrity, not just headcount.

These aren’t pie-in-the-sky; they’re feasible, drawn from global best practices. Fail here, and COA invites perpetual skepticism.

The Accountability Ladder: Cordoba’s Personal Perils

Chair Cordoba, a former National Telecommunications Commission (NTC) head with a controversial past (remember the ABS-CBN shutdown?), now climbs a slippery ladder of liabilities. Administratively, the Ombudsman could sanction him under Republic Act (RA) 6770 (The Ombudsman Act of 1989) for supervisory negligence—ignoring Lipana’s conflict or failing to escalate risks. Criminally, graft charges (Republic Act No. 3019, the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act) loom if evidence ties him to cover-ups, though personal kickbacks seem unlikely without proof; plunder (Republic Act No. 7080, the Anti-Plunder Law) for billions misused would require direct collusion. Politically, Senate pressure could force resignation, as with past officials, while reputational hits—amplified by his history—could end his career.

Defenses? Structural constraints and cooperation might mitigate, but leadership demands foresight. When the poor suffer floods while billions vanish, a leader’s job isn’t to blame the staff—it’s to sound the alarm or step aside.

The Ripple Effect: A Nation Submerged in Consequences

This scandal’s waves crash far beyond Bulacan.

- Economically, wasted P100 billion-plus deters investors, balloons debt, and starves real infrastructure—leaving us vulnerable to climate fury, where substandard dikes mean billions more in disaster aid.

- Socially, trust evaporates: Flood victims in displaced communities, already battered by typhoons claiming lives, see their taxes fund phantoms. Protests brew, cynicism festers, widening the gulf between governed and governors.

- Politically, implicated senators face probes, cabinet shakeups loom (DPWH Secretary Bonoan on the hot seat), and dynasties like the Discayas expose cronyism’s grip.

- Institutionally, if unreformed, procurement grinds to a halt, delaying vital projects.

Humanly, it’s gut-wrenching: Deaths from preventable floods, families uprooted, children wading to school. In a warming world, this isn’t abstraction—it’s moral failure.

Toward Dry Ground: A Call for True Accountability

This flood control fiasco isn’t just corruption; it’s a litmus test for our democracy. COA’s lapses, shielded by “manpower” whispers, reveal a system where watchdogs whimper while the powerful plunder. Demand better: Senate, restore positions with strings; civil society, crowdsource verifications; Cordoba, reform or resign.

In the end, facts don’t lie—only leaders do when they hide behind them. Until accountability flows freely, we’ll keep drowning in the deluge of our own making. Share this if you’re outraged; act if you’re able.

Yours in the cave,

Louis “Barok” C. Biraogo

Kweba ni Barok

Key Citations

- “COA Cites ‘Lack of Manpower’ for Unchecked Anomalous Flood Control Projects.” GMA News Online, GMA Integrated News, 13 Oct. 2025.

- Republic Act No. 6770. Lawphil.net. Accessed 15 Oct. 2025.

- Republic Act No. 3019. Lawphil.net. Accessed 15 Oct. 2025.

- Republic Act No. 7080. Lawphil.net, . Accessed 15 Oct. 2025.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment