A Scandal That Hisses with Corruption and Cover-Ups

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — October 20, 2025

I. The Circus of Scandal: A Drama Drenched in Suspense

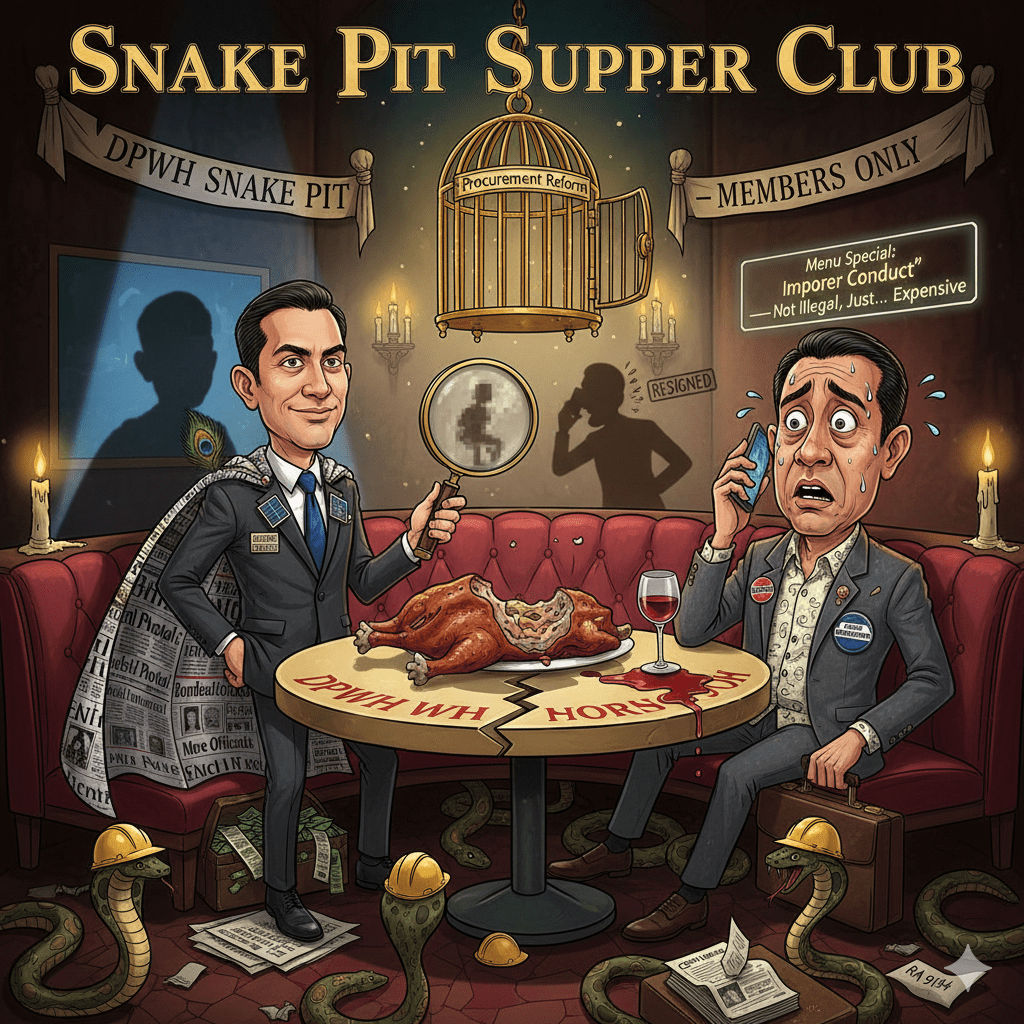

IN A Manila dive, Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) officials and contractors clink glasses, murmuring about billion-peso contracts like crooked kingpins in a B-movie sting operation. Enter Representative Leandro Leviste, Batangas’ brash young firebrand, hurling accusations like Molotov cocktails: “More officials are tangled in this contractor web,” he smirks, teasing a mystery photo of one caught in the act. The opening salvo? Undersecretary Arrey Perez’s sudden resignation on October 17, 2025, scuttling off like a stagehand fleeing a collapsing set. Across the stage, DPWH Secretary Vince Dizon, the self-proclaimed reformer, stumbles with a defense that’s pure tragicomedy: “It’s not illegal, just… improper.” Improper? That’s like calling a bank heist a minor etiquette slip.

The plot thickens when Dizon’s office, in a move straight out of a low-rent thriller, dials Leviste mid-press conference on October 16, like a frantic producer trying to silence a rogue star (Inquirer, Oct 18, 2025). Who’s the shadowy figure in that restaurant snapshot? Why the desperate call? This isn’t just a budget spat—it’s a high-stakes political cage match where every player’s hiding a blade, and the audience is left guessing who’ll bleed first.

II. The Legal Slaughterhouse: Carving Up the Arguments

A. Leviste’s Headline Hustle: Grandstanding or Grit?

Leviste struts into the arena like a matador, waving vague allegations like a red cape: “More officials,” “one was photographed.” But this isn’t a bullfight—it’s a legal bloodbath, and his evidence is flimsier than a Manila traffic cop’s patience. Trial by press release isn’t oversight; it’s a circus act that flirts with defamation. The 1987 Constitution‘s due process clause and the Supreme Court’s Ang Tibay v. Court of Industrial Relations (G.R. No. L-46496, 1940) demand hard evidence, not whispers of “sources.” Naming Perez and hinting at others without receipts risks libel under Article 353 of the Revised Penal Code (Republic Act No. 3815), and the presumption of innocence isn’t a suggestion—it’s a mandate. Leviste’s hearsay haymaker might dazzle the crowd, but it’s a legal dud that could land him in court defending his own hide.

What’s his game? As the scion of Senator Loren Legarda and ex-Governor Antonio Leviste, he’s got the pedigree for a Senate run or a power grab in Batangas. Is this a crusade to slay corruption, or a stunt to humiliate the Marcos Jr. administration and polish his reformist halo? X posts call him out for “pass the message” theatrics (X post analysis), and the stench of ambition is hard to miss. If he’s got no smoking gun, he’s not a whistleblower—he’s a showboat.

B. Dizon’s Defensive Debacle: Reform or Ruin?

Dizon, the supposed reformer, steps into the ring and promptly faceplants with his “not illegal, just improper” defense. For a Cabinet secretary, “improper” isn’t a minor flub—it’s a scarlet letter. Republic Act No. 6713 (Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees) (RA 6713) doesn’t just frown on the appearance of impropriety; it demands officials avoid it like a plague. Off-site meetings with contractors in swanky restaurants? That’s a screaming violation of Republic Act No. 9184 (Government Procurement Reform Act) (RA 9184), which mandates transparency and competitive bidding to keep contractor vultures at bay. Dizon’s shrug—admitting his team’s cozy dinners—mocks the procurement safeguards he’s sworn to uphold.

How does a “reformer” miss the contractor infestation in his own house? As Perez’s appointer, Dizon’s either blind or complicit. His mid-presser call to Leviste reeks of panic, not principle, and his failure to log these meetings under RA 9184‘s strict controls is a managerial disaster. The Supreme Court’s Cambe v. Office of the Ombudsman (G.R. Nos. 212014-15, 2016) nailed DPWH officials for less, proving procurement shenanigans can lead to cuffs. Dizon’s not just dodging Leviste’s punches; he’s dodging accountability, and that’s the real scandal.

III. The Puppet Strings: Unmasking the True Motives

What’s pulling the strings behind this drama? Leviste, the solar tycoon turned congressman, might be fighting for Batangas’ budget share, ensuring his district gets a juicier slice of the infrastructure pie. Or is he eyeing a Senate seat, styling himself as the anti-corruption crusader to eclipse his mother’s legacy? Maybe it’s personal—a Batangas-Pampanga feud with Dizon’s camp. His refusal to share specifics with Dizon smells like a power play, not a reformist handshake.

Dizon, a Marcos Jr. loyalist with 26 years in the bureaucratic trenches, is either shielding his team out of loyalty or covering his own tracks. Is he scrambling to save the administration from a PR nightmare, even if it means papering over the rot? His “reformer” badge is tarnishing fast—caught off-guard by his team’s indiscretions, he’s either naive or neck-deep in the DPWH swamp. That mid-presser call screams damage control, not leadership. Is he the hero cleaning house, or the fall guy for a system that’s been dirty for decades?

IV. The Great Escape: Dodging the Scandal’s Jaws

A. Dizon’s Desperate Gambits

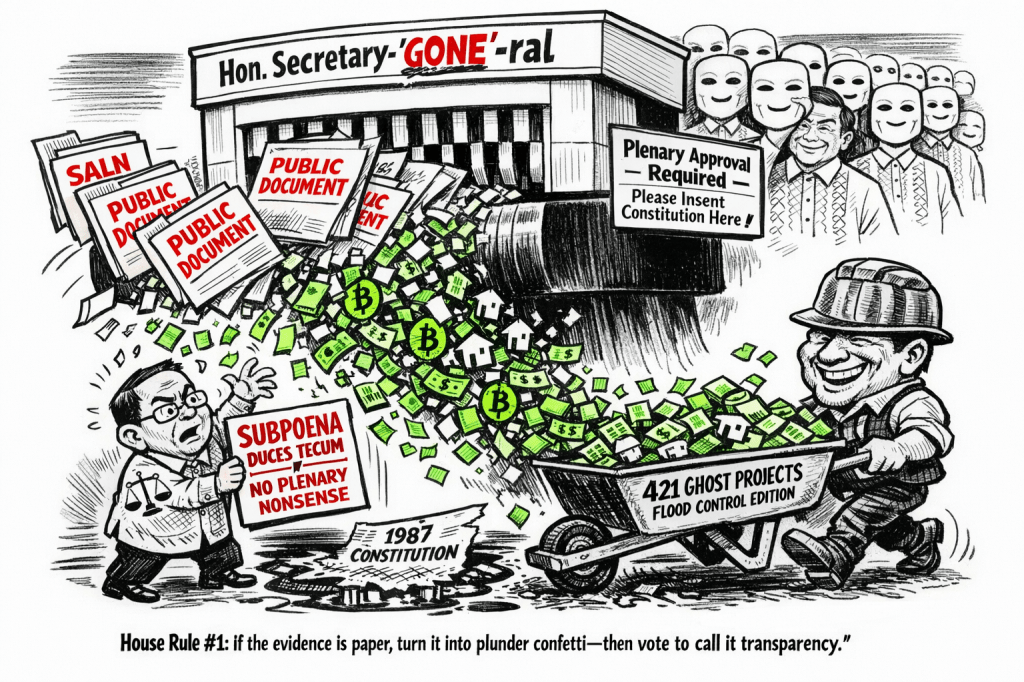

Dizon’s on a tightrope with no net. The weak play: a toothless internal review that buries the issue in red tape. The bold move: a full purge of tainted officials and a data dump of the DPWH budget—every peso, every district, every contractor. RA 9184 and Commission on Audit (COA) rules demand transparency, so why not call Leviste’s bluff? Publish the National Expenditure Program (NEP) and General Appropriations Bill (GAB) breakdowns, log every contractor meeting, and invite COA or Government Procurement Policy Board (GPPB) to audit the books (COA Guidelines). If he’s clean, it’s a checkmate. If not, he’s cooked. Resigning to save the administration’s face is an option, but only if that mystery photo shows him handing out briefcases of cash. What’s it gonna be, Vince—transparency or a deeper hole?

B. Leviste’s High-Stakes Wager

Leviste can keep milking the media spotlight, but that risks credibility fatigue—voters tire of noise without substance. The harder path: file a formal complaint with the Office of the Ombudsman under Republic Act No. 6770 (RA 6770), the Ombudsman Act, swear to his evidence (that photo better be good), and face legal scrutiny. RA 9184 and Republic Act No. 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act) demand hard proof, not presser theatrics. He could also channel his fire into a House oversight hearing, subpoenaing documents and grilling DPWH officials. Will he step up to the legal plate, or keep swinging for the headlines?

V. The Aftermath: A Scandal’s Toxic Ripples

A. Legal Quagmire

Can this scandal spark RA 3019 prosecutions? Maybe, but the Supreme Court’s Navales v. People (G.R. Nos. 219598 & 220108, Aug. 7, 2024) sets a high bar: procurement lapses alone don’t cut it—prosecutors need bank records, quid pro quo texts, or contractor testimony proving bad faith or manifest partiality. That mystery photo might be a bombshell, but without a paper trail, it’s just a Polaroid in a storm. Administrative sanctions under RA 6713 for ethical breaches are more likely—suspensions or dismissals for improper conduct are easier to stick than criminal convictions.

B. Political Bloodbath

Dizon’s on thin ice. If hard evidence surfaces, he could be forced to resign, joining the long line of DPWH chiefs felled by scandal. Leviste’s fate hinges on his proof: deliver a smoking gun, and he’s a hero; come up empty, and he’s a grandstanding gadfly. The Marcos Jr. administration faces collateral damage—another DPWH scandal fuels public distrust, especially amid flood control failures (Flood Project Inquiries).

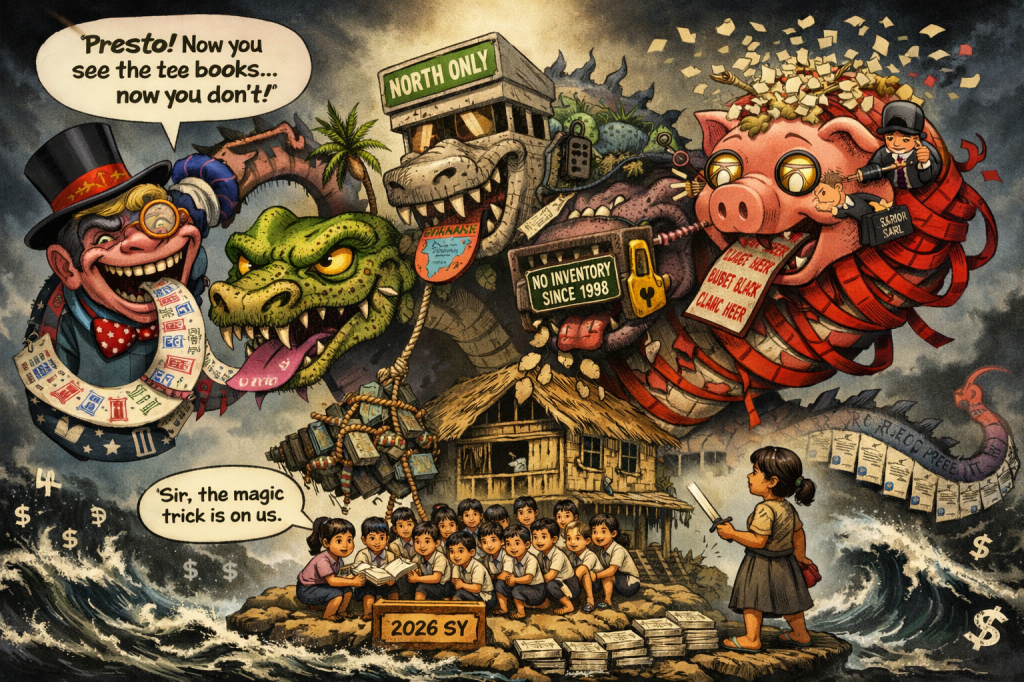

C. Systemic Shockwaves

Will this force real procurement reform, or just teach contractors to be sneakier? RA 9184 and RA 6713 could see amendments—stricter meeting logs, harsher penalties for off-site deals—but DPWH’s history (20% kickbacks in flood projects) suggests corruption just evolves (Inquirer Flood Report). The Supreme Court’s Belgica v. Ochoa (G.R. No. 208566, 2013) killed Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF) insertions; maybe Leviste’s push could do the same for DPWH. But without radical openness, it’s just another episode in the DPWH’s endless telenovela of graft.

VI. The Barok Guillotine: No-Holds-Barred Verdict

- To Dizon: Stop playing spin doctor and start running your department. Release the budget data—NEP, GAB, all of it—today. Launch a real probe, not a whitewash, and if you find rot, swing the axe in public. Your “improper” excuse is a confession of failure, and RA 6713 doesn’t grade on a curve. Invite COA to audit now, or watch the scandal swallow you whole.

- To Leviste: Put up or shut up. Take that mystery photo and your “sources” to the Ombudsman, file a case under RA 3019, and swear to it under oath. Press conferences aren’t justice—courts are. If you’ve got the goods, prove it where it counts, not on a stage for claps. RA 9184 deserves better than your hearsay.

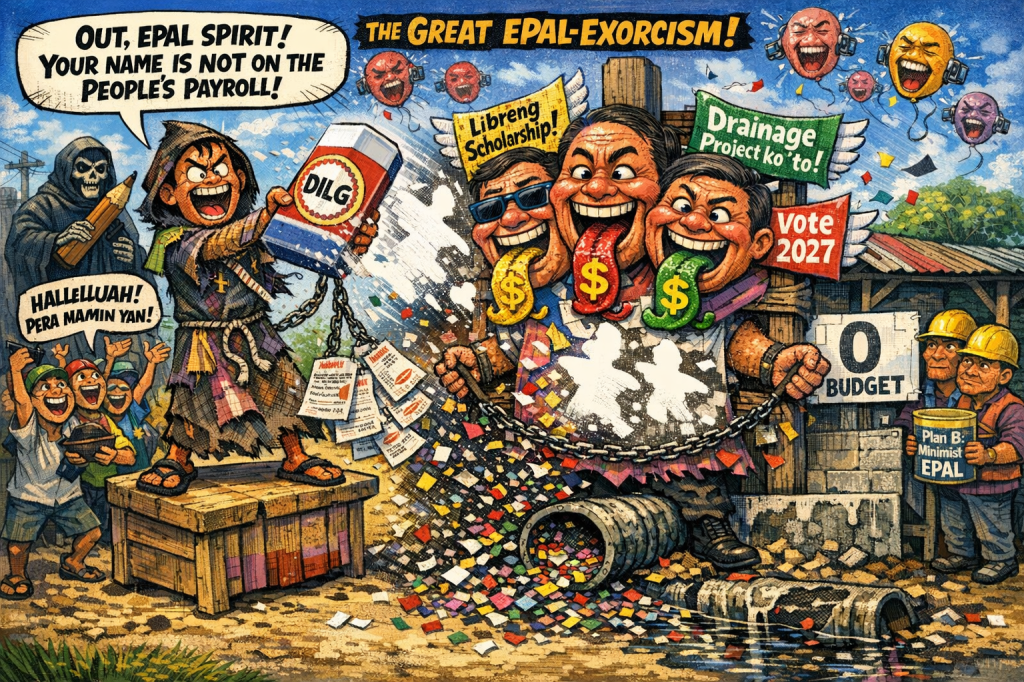

- To the Public: Don’t get suckered by the he-said, she-said drama. Demand radical transparency—every contract, every meeting, every peso in the DPWH budget. RA 9184 and the 1987 Constitution give you the right to know. Shine a light on the snakes, or they’ll just slither deeper into the jungle.

This scandal isn’t just Leviste vs. Dizon—it’s a test of whether the Philippines can break the cycle of procurement corruption or watch it play on repeat. The clock’s ticking, and the snakes are watching.

Key Citations

- Escosio, Jan. “Leandro Leviste Says More DPWH Officials Linked to Contractors.” Inquirer.net, 18 Oct. 2025.

- Biraogo, Louis C. “Contractor Infestation at DPWH: Reform Hero Dizon Dodges Leviste’s Hearsay Haymaker—Graft or Grandstanding?” Kweba ni Barok, 17 Oct. 2025.

- Ang Tibay v. Court of Industrial Relations, G.R. No. L-46496, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 27 Feb. 1940.

- Belgica v. Ochoa, G.R. No. 208566, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 19 Nov. 2013.

- Navales v. People of the Philippines, G.R. Nos. 219598 & 220108, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 7 Aug. 2024. Accessed 19 Oct. 2025.

- Cambe v. Office of the Ombudsman, G.R. Nos. 212014-15, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 7 Dec. 2016. Accessed 19 Oct. 2025.

- “1987 Constitution.” Official Gazette, Republic of the Philippines. Accessed 19 Oct. 2025.

- Republic Act No. 3019: Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. Republic of the Philippines, 17 Aug. 1960.

- Act No. 3815: An Act Revising the Penal Code and Other Penal Laws. Republic of the Philippines, 8 Dec. 1930. Accessed 19 Oct. 2025.

- Republic Act No. 3815: Revised Penal Code. Republic of the Philippines, 8 Dec. 1930.

- Republic Act No. 6713: Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees. Republic of the Philippines, 20 Feb. 1989.

- Republic Act No. 6770: The Ombudsman Act of 1989. Republic of the Philippines, 17 Nov. 1989.

- Republic Act No. 9184: Government Procurement Reform Act. Republic of the Philippines, 10 Jan. 2003.

- “Department of Public Works and Highways.” Wikipedia.

- Volume I: Accounting Policies, Guidelines, and Procedures and Illustrative Accounting Entries. Commission on Audit, Republic of the Philippines. Accessed 19 Oct. 2025.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment