Discayas’ Heart Signs vs. Andres’ Hard Line: No Loot, No Sanctuary

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — October 23, 2025

WELCOME to the latest episode of As the Senate Turns, where budget hearings for the Department of Justice (DOJ) morph into a circus of self-righteous posturing and legal hair-splitting. This week’s melodrama: Senator Rodante Marcoleta, the sudden champion of statutory purity, locks horns with DOJ’s Fredderick Vida and Jesse Andres, the self-appointed guardians of the public purse. At the center of this farce are Sarah and Curlee Discaya, the Bonnie and Clyde of flood control contracts, whose bid for the Witness Protection Program (WPP) under Republic Act (RA) No. 6981 has everyone clutching their pearls and their law books. Buckle up, because this ₱118.5 billion flood control scandal is drowning in absurdity, and we’re here to skewer every soggy argument.

The Opening Act: A Budget Hearing or a Political Pantomime?

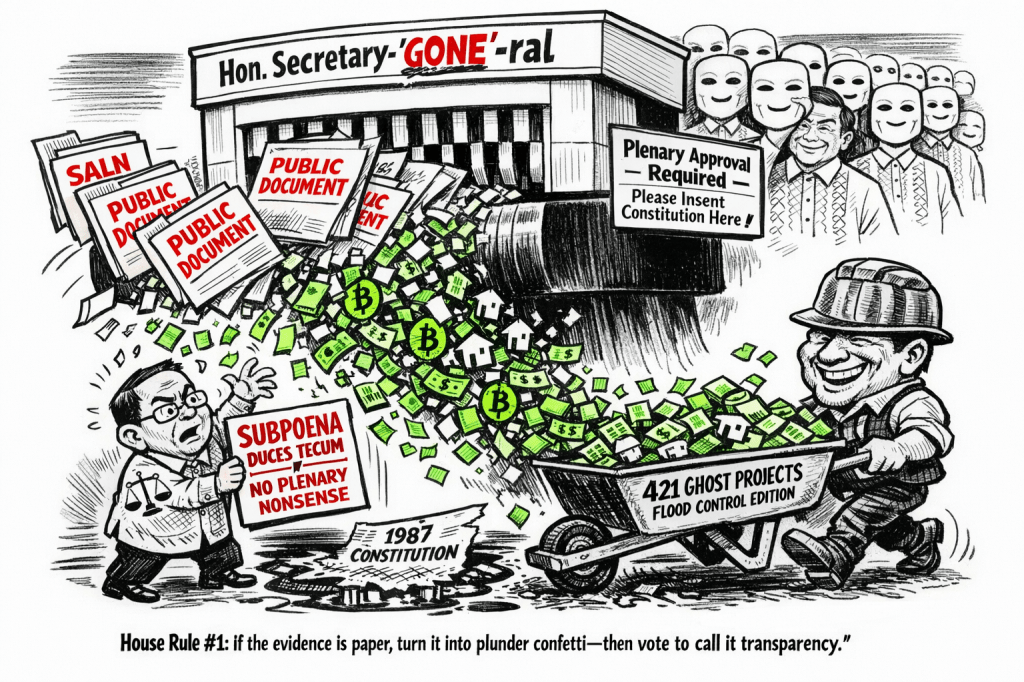

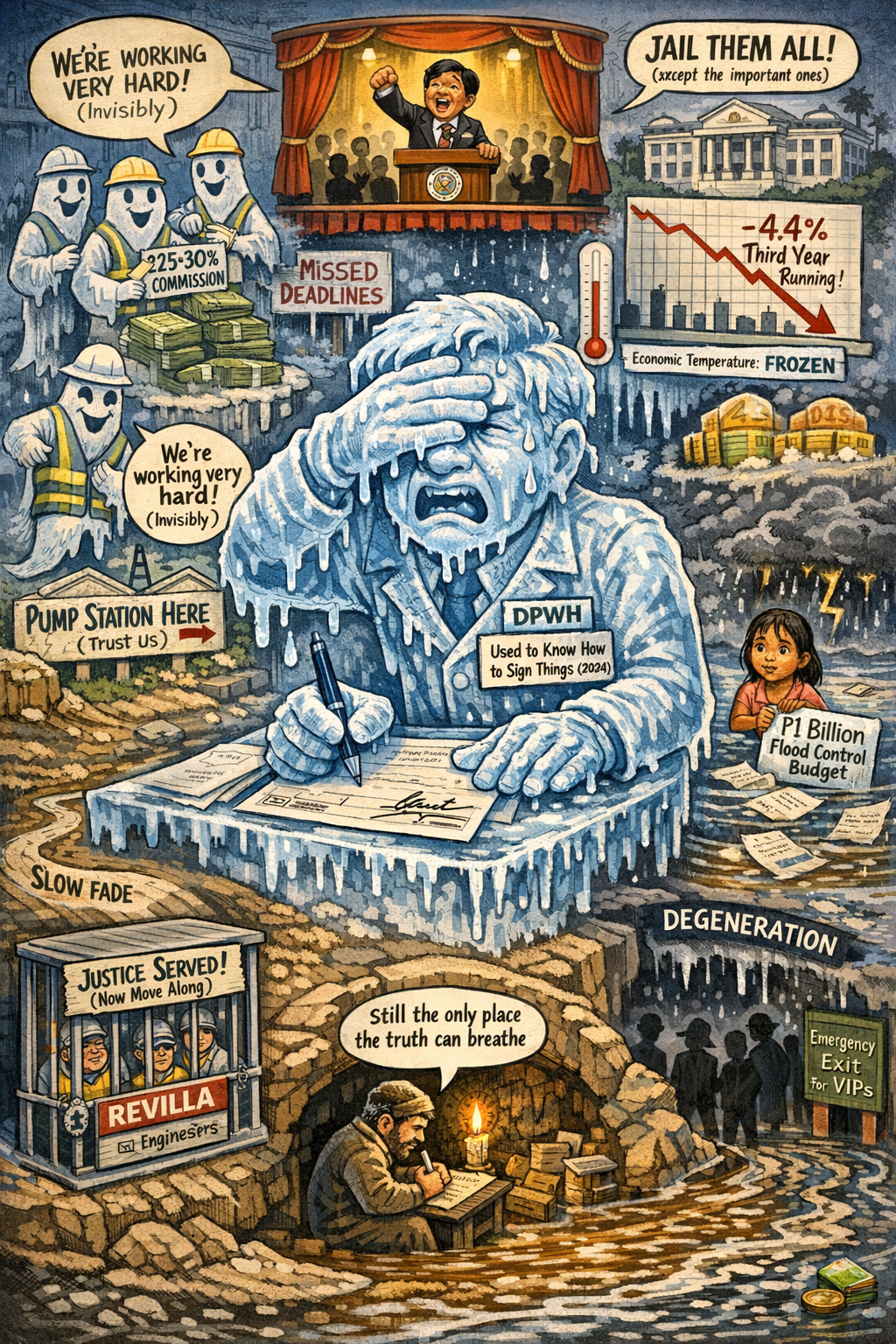

The Senate Committee on Finance is supposedly deliberating the DOJ’s ₱43.65-billion budget for 2026, but what we get is a masterclass in political Cover Your Assets (CYA). Senator Marcoleta, with the zeal of a televangelist discovering the Constitution, rails against the DOJ’s demand that the Discayas cough up their alleged ill-gotten gains before entering the WPP. DOJ’s Officer-in-Charge (OIC) Fredderick Vida and Undersecretary Jesse Andres, meanwhile, don their capes as righteous restitutionists, insisting that returning stolen money is just good manners. And the Discayas? They’re the whistleblowing profiteers, flashing heart signs at Senate hearings like they’re auditioning for a rom-com, not exposing a ₱118.5 billion corruption swamp. This isn’t oversight; it’s a three-ring circus with no ringmaster.

The Legal Duel: Textualism vs. Bureaucratic Overreach

Let’s dive into the legal mud-wrestling, where RA 6981, the Witness Protection, Security and Benefit Act, is the battleground. The core question: Can the DOJ demand restitution as a prerequisite for WPP admission, or are they just making it up as they go?

Marcoleta’s Plain-Text Crusade: Heroic or Hypocritical?

Marcoleta’s argument is simple: Section 10 of RA 6981 lists six clear criteria for WPP admission—grave felony, necessity of testimony, no other direct evidence, corroborated testimony, not the most guilty, and no moral turpitude convictions. Restitution? Not in the fine print. His soundbite—”Kung ipipilit na merong restitution kahit wala sa batas, how can you process the application?”—is a lawyerly mic drop. The law’s title screams protection, not punishment, and piling on preconditions risks scaring off witnesses who could finger the real masterminds.

But let’s not canonize Marcoleta just yet. His “butete at sapsap” (goby and ponyfish) quip about focusing on small fry while the big fish swim free raises eyebrows. Is he a principled textualist or a strategic puppeteer? The Discayas, after all, aren’t innocent whistleblowers—they’re the alleged “King and Queen” of a ₱31 billion flood control racket. Marcoleta’s insistence on protecting their WPP bid feels less like a defense of statutory purity and more like a calculated move to keep the spotlight off bigger players. His claim, “Hindi ko dinidepensahan ang mga taong ‘yun,” sounds like a politician protesting too much. If he’s so keen on catching masterminds, why not push for clearer laws instead of grandstanding in hearings? His rhetoric smells like a bait-and-switch, and I’m not buying the popcorn.

DOJ’s Restitution Rant: Noble or Nonsensical?

On the other side, DOJ’s Vida and Andres are waving Section 5(f) of RA 6981 like a magic wand. This provision requires a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) outlining a witness’s responsibilities, including “complying with legal obligations and civil judgments.” Andres doubles down, citing the Civil Code’s unjust enrichment principles (Articles 22 and 2142) to argue that restitution is a natural extension of legal duties. Former DOJ Secretary (now Ombudsman) Jesus Crispin Remulla’s “good faith” test—return the money to prove you’re serious—gets a nod from Vida, who seems to think the WPP shouldn’t be a “Get Out of Jail and Keep the Cash Free” card. Credit where it’s due: harmonizing RA 6981 with broader anti-corruption laws is a defensible legal move, and ensuring witnesses don’t profit from crimes aligns with public interest. The Supreme Court’s ruling in Yon Mitori International Industries v. Banco De Oro (G.R. No. 225538, 2020) supports recovering ill-gotten gains to uphold justice.

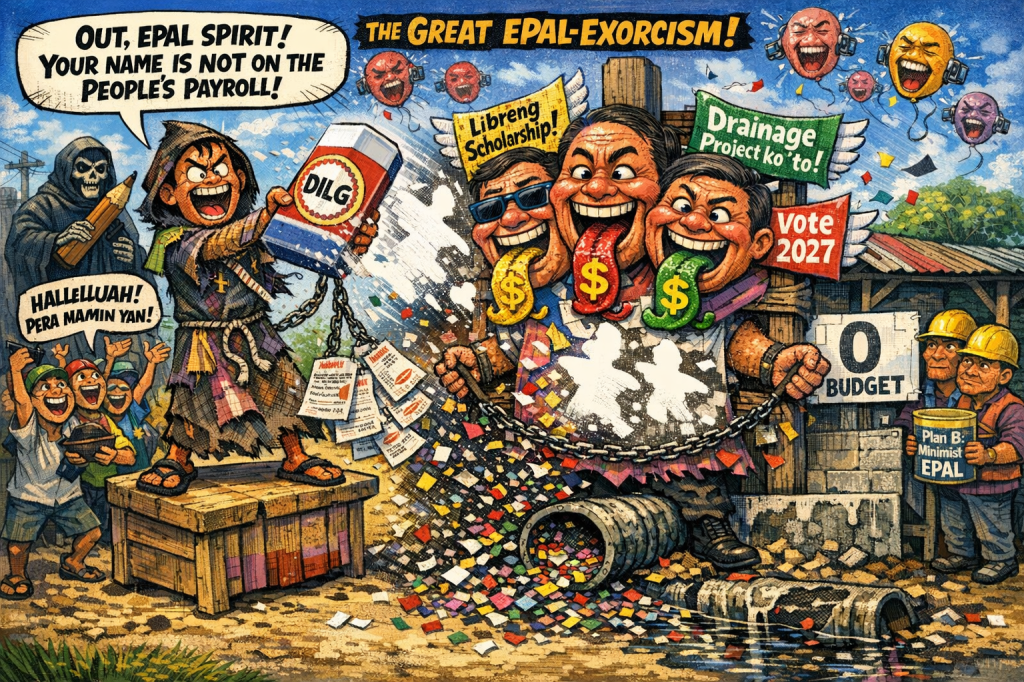

But here’s where the DOJ trips over its own cape. If restitution is a process, not a precondition, why does their messaging sound like a shakedown? Andres’ line—‘matagal naman po ang paraan’ (the process takes a long time)—feels like a bureaucratic dodge, hinting at a process more tangled than a Manila flood drain. Asset tracing is slow, sure, but demanding restitution upfront without clear guidelines is a recipe for chaos. The Discayas’ withdrawal from the Independent Commission for Infrastructure (ICI) probe—after ICI’s Rogelio Singson said no one’s qualified as a state witness yet—shows the chilling effect of this muddled policy. If the DOJ can’t articulate whether restitution is a hard prerequisite or just an MOA promise, they’re handing corrupt officials a get-out-of-jail-free card by scaring off witnesses. And let’s talk about consistency: reports indicate the DOJ sometimes grants interim protection without restitution demands. Selective enforcement much? That’s a violation of RA 6713‘s ethical standards for public officials, and it reeks of politicized gatekeeping.

The Precedent Pit: What the Courts Say

The Supreme Court has waded into this mess before, and it’s not kind to either side’s excesses. In Ampatuan v. De Lima (G.R. No. 197291, 2013), the Court distinguished WPP admission (an administrative act under RA 6981) from discharge as a state witness (a judicial act under Rule 119, Section 17). Marcoleta’s right that the DOJ can’t impose extra-statutory hurdles, but the Court also upheld the DOJ’s discretion to set MOA terms under Section 5. Meanwhile, Republic v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. No. 152154, 2003) clarifies that immunity for cooperating witnesses is transactional—cooperation is king, but no one gets a free pass to keep stolen loot. The DOJ’s restitution push aligns with this, but only if it’s post-admission and judicially supervised, not a preemptive penalty. In Secretary Teofisto Guingona, Jr. v. Court of Appeals (G.R. No. 125532, 1998), the Court clarified RA 6981’s witness categories and rejected pre-admission corroboration as a bar, focusing on statutory criteria without extra hurdles—echoing why the DOJ can’t just invent restitution demands. The DOJ’s current stance risks flipping the script, imposing civil penalties before conviction, which could trigger due process challenges under Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution.

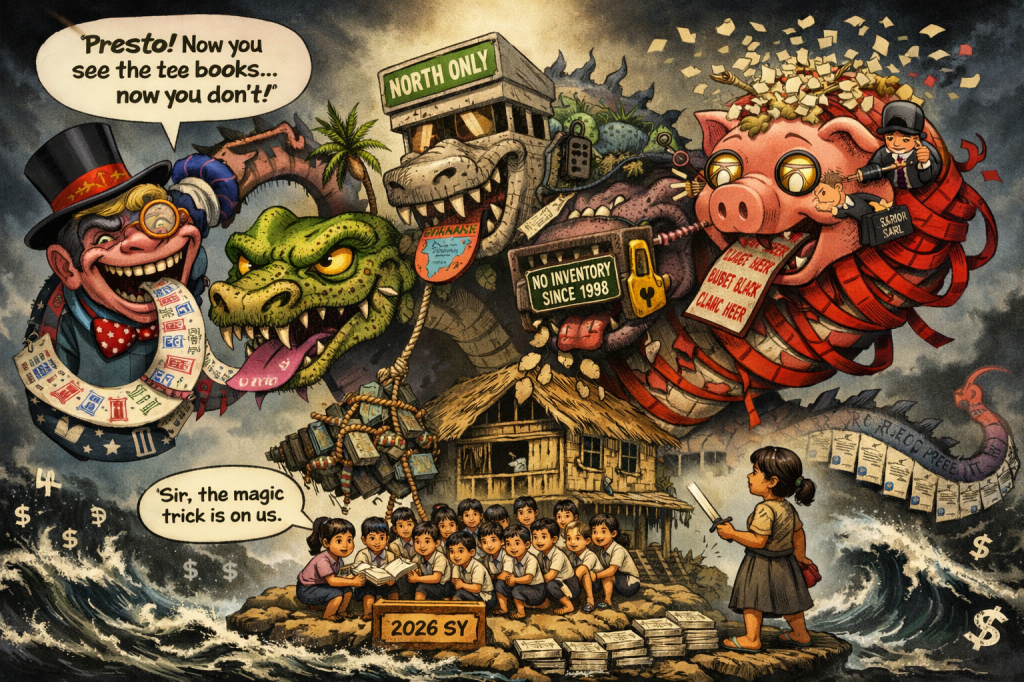

The Bigger Picture: ₱118.5 Billion Down the Drain

Let’s zoom out. This isn’t just a legal spat—it’s a symptom of a ₱118.5 billion flood control scandal that’s left Manila drowning in incompetence and greed. That’s not pocket change; it’s enough to build 59,250 classrooms, 1,185 hospitals, or 236,000 low-cost homes (Philippine Statistics Authority). Instead, we’ve got overpriced dikes, “ghost” projects, and kickbacks up to 30%, all while typhoons turn streets into rivers and spark youth protests (Manila Times). The Discayas’ allegations—naming congressmen, Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) officials, and even Speaker Martin Romualdez (before a convenient retraction)—point to a “layered” corruption architecture that’s as sophisticated as it is sickening (PhilSTAR). This legal tug-of-war over WPP isn’t academic; it’s about whether the public gets its money back and whether future floods claim more lives. Every delay, every witness lost, is another nail in the coffin of public trust.

The Heart Sign Hustle: The Discayas’ Dubious Dance

And then there’s Sarah and Curlee Discaya, the self-styled whistleblowers who’ve turned Senate hearings into a rom-com audition with their “heart sign” antics. Let’s not kid ourselves: these two aren’t Robin Hoods. Dubbed the “Nexus of Corruption,” they allegedly rigged ₱31 billion in contracts through cozy deals and kickbacks (South China Morning Post). Their sudden urge to spill the beans reeks of self-preservation, not civic duty. Their withdrawal from the ICI probe—after Singson’s comment about no one qualifying as a state witness—suggests they’re playing hard to get, hoping for a better deal. And that inconsistent testimony? Naming Romualdez, then backtracking? It’s less “whistleblower courage” and more “calculated chaos.” If the DOJ thinks they’re credible, I’ve got a flood-proof bridge to sell them. The Discayas’ heart signs might charm the cameras, but their hands aren’t clean, and their credibility is as shaky as a substandard dike.

Conclusion: Stop the Show, Fix the System

This whole mess is a masterclass in how to botch a corruption probe. Marcoleta’s textualist tantrum has a kernel of truth but smells like political theater. The DOJ’s restitution crusade is noble in theory but clumsy in execution, turning the WPP into a bureaucratic boondoggle. And the Discayas? They’re playing everyone, heart signs and all. Here’s how to cut through the noise:

- To the DOJ: Publish a f@#%ing guideline. Spell out whether restitution is a prerequisite, an MOA term, or a discretionary factor. Transparency stops you from looking like political pawns or incompetent gatekeepers. Coordinate with the Office of the Ombudsman and Sandiganbayan to trace assets after protecting witnesses, not before. And maybe hire a PR team to stop sounding like you’re shaking down whistleblowers.

- To the Senate: Stop grandstanding and legislate. If RA 6981‘s ambiguity is causing this circus, amend it. Clarify the restitution rules and tighten oversight without turning hearings into a soap opera. Marcoleta, if you’re so worried about masterminds, push for laws that make it easier to protect witnesses, not harder to prosecute the big fish.

- To the Public: Follow the money, not the soundbites. The real scandal isn’t this legal spat—it’s the ₱118.5 billion that could’ve saved lives but instead lined pockets. Demand accountability, not just from the Discayas, but from the congressmen and DPWH officials still dodging the spotlight. And maybe stop cheering for heart signs—they’re not love letters; they’re a distraction.

This flood control scandal, and the WPP drama at its heart, isn’t just about law—it’s about lives lost to corruption and infrastructure that fails when the rains come. Until everyone stops playing to the gallery and starts fixing the system, we’re all just treading water in a sea of hypocrisy.

Key Citations

- Ampatuan v. De Lima. G.R. No. 197291, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 3 Apr. 2013.

- Republic of the Philippines. Republic Act No. 386: An Act to Ordain and Institute the Civil Code of the Philippines. 18 June 1949. Official Gazette.

- “Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees.” Republic Act No. 6713, Lawphil Project, 20 Feb. 1989.

- “Discaya: I Have No Direct Transaction with Romualdez, Co in Project Kickbacks.” Philstar.com, 9 Sept. 2025. Accessed 22 Oct. 2025.

- Chan, Valerie. “Meet the Free-Spending Filipino Couple Dubbed ‘the King and Queen of Flood Control’.” South China Morning Post, 4 Sept. 2025.

- Domingo, Leilanie. “DoJ Not Amused by Sarah Dacera’s Heart Sign.” INQUIRER.net, 5 Jan. 2024.

- “No Letup in Rallies.” Manila Times, 16 Oct. 2025.

- Ombay, Giselle. “Marcoleta Grills DOJ over Discayas’ State Witness Bid.” GMA Integrated News, 21 Oct. 2025.

- Republic of the Philippines v. Sandiganbayan. G.R. No. 152154, July 15, 2003. Supreme Court of the Philippines. Accessed 22 Oct. 2025.

- Secretary Teofisto Guingona, Jr., et al., Petitioners, vs. Court of Appeals and Rodolfo Pineda, Respondents. G.R. No. 125532, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 10 July 1998.

- “The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines.” Official Gazette.

- “Witness Protection, Security and Benefit Act.” Republic Act No. 6981, Official Gazette, 24 Apr. 1991.

- Yon Mitori International Industries v. Banco De Oro. G.R. No. 225538, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 26 Feb. 2020.

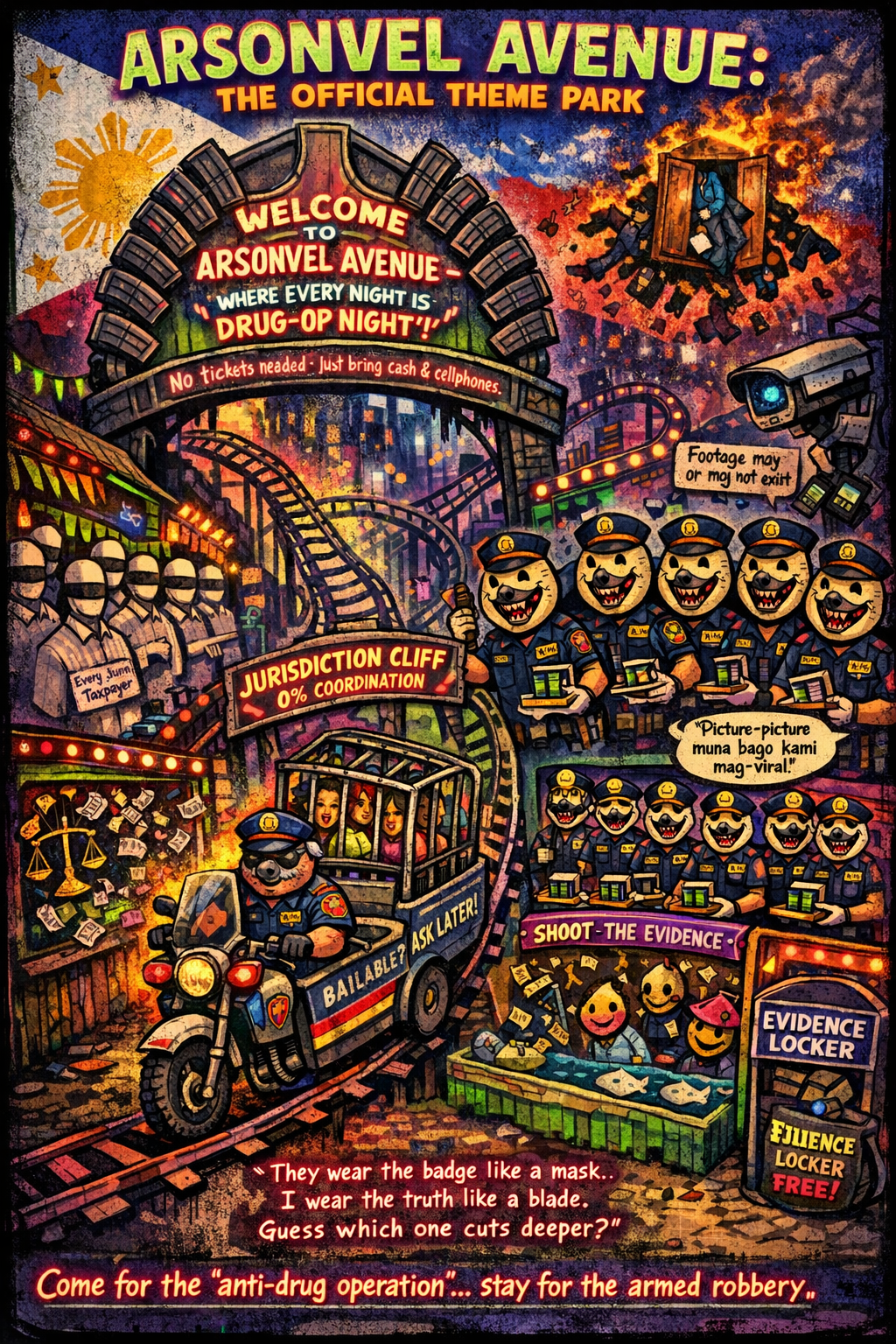

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

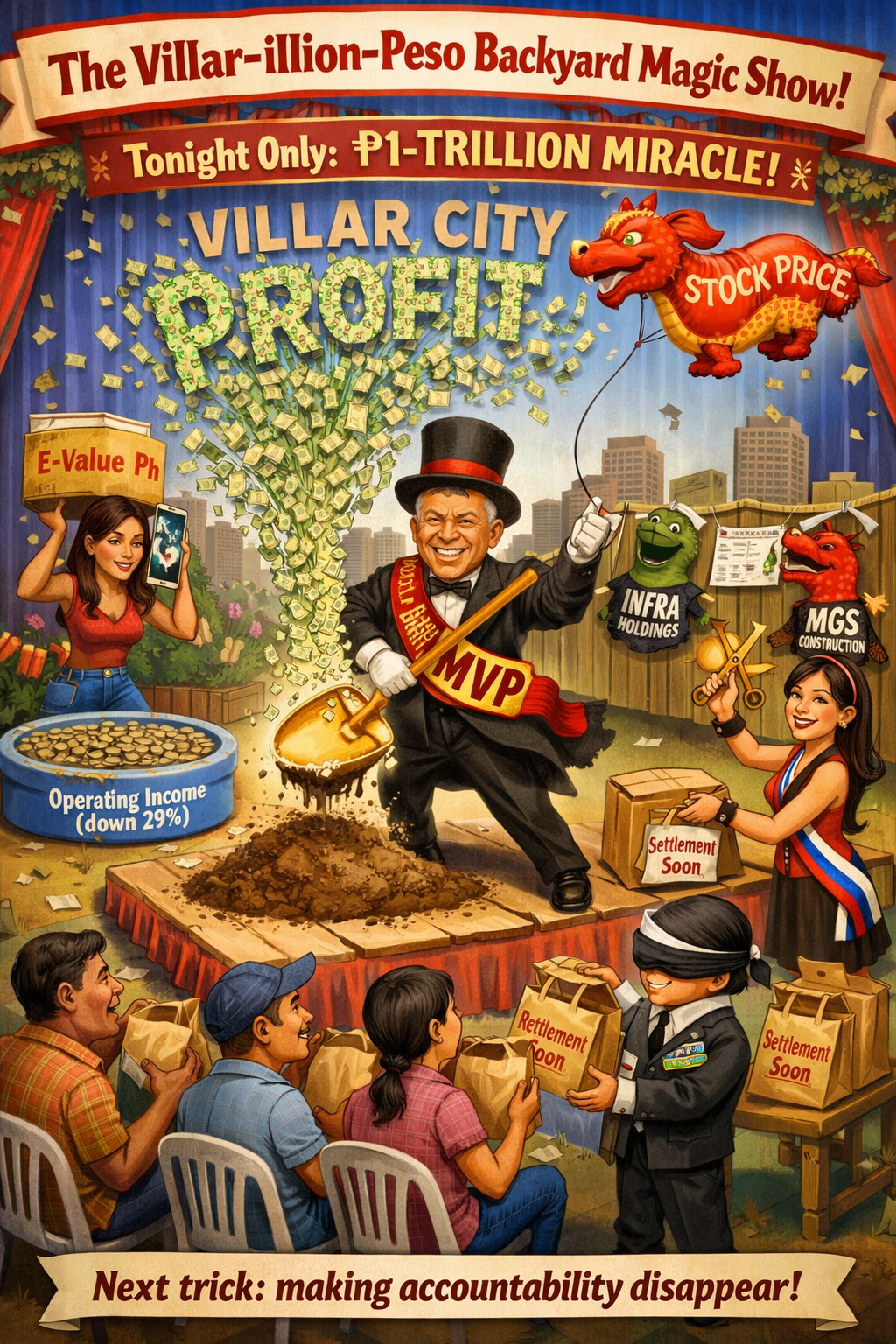

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment