A Tale of Blacklists and Broken Systems, Starring the Same Old Villains

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — October 22, 2025

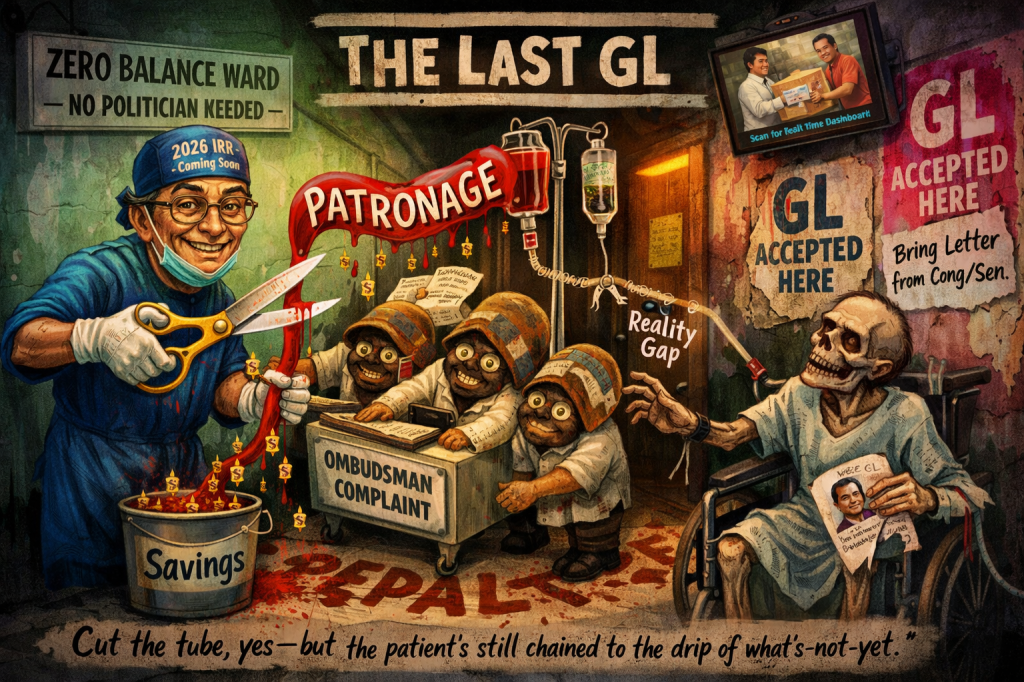

HALLELUJAH! Another year, another “landmark” anti-corruption law in the Philippines, trotted out like a shiny new jeepney with a Ferrari engine—except the chassis is still rusted from decades of graft, and the driver’s got a side hustle in kickbacks. Enter the New Government Procurement Act (NGPA, Republic Act No. 12009), signed into law on July 20, 2024, and hailed by Department of Budget and Management (DBM) Secretary Amenah Pangandaman as the great door-slammer on corruption and collusion. In a press release that reads like a Hallmark card for fiscal rectitude, she declares: “The old tricks of palit-pangalan, palit-ulo, and dummy company owners will no longer work.” We’re “closing the doors” on shady schemes, she insists, thanks to mandatory beneficial ownership disclosure. It’s enough to make a jaded legal hack like me choke on my tsokolate.

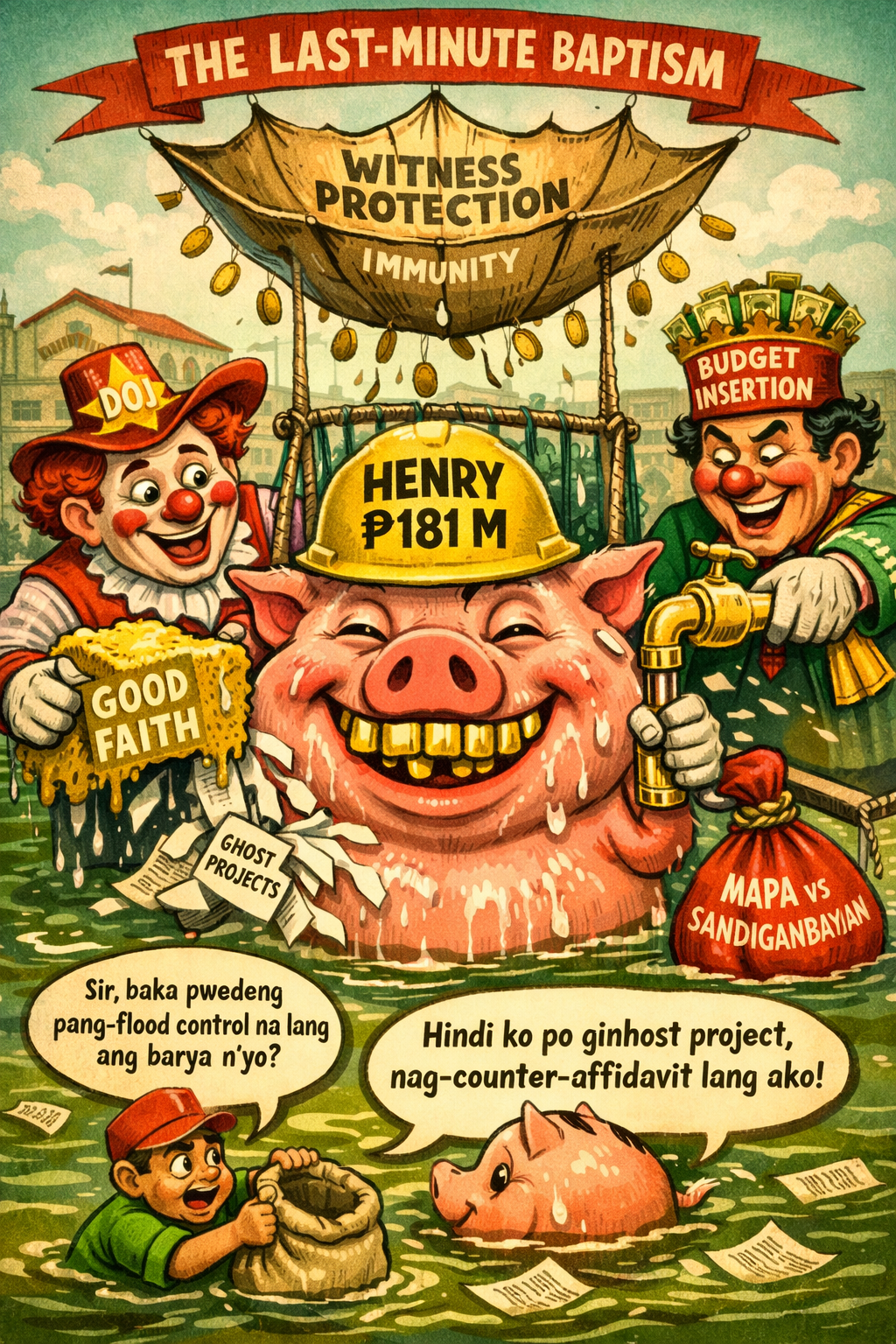

Spare me the champagne toasts, Madam Secretary. This isn’t closing doors; it’s installing a screen door during a typhoon. Pangandaman’s optimism crashes headlong into the grim farce of Philippine procurement history—a saga of scandals where “transparency” meant hiding envelopes under the table. Remember the Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF) pork barrel heist? Billions siphoned through ghost non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and rigged bids, leaving schools half-built and taxpayers footing the bill for lawmakers’ vanity projects. Or the COVID-19 supply scams, where overpriced masks and test kits flowed to cronies via “emergency” exemptions under the old Government Procurement Reform Act (RA 9184)? These weren’t rogue anomalies; they were the system working as designed. And now, the DBM waves NGPA like a magic wand, ignoring the 2023 Government Procurement Policy Board–Technical Support Office (GPPB-TSO) bombshell: 65.8% of bidders sharing common owners. That’s not a bug, folks—it’s the feature. Systemic rot so deep that even a “powerful feature” like beneficial ownership disclosure feels like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

The Legal Scalpel: NGPA’s Paper Promises vs. the Fine Print’s Escape Hatches

Let’s give credit where it’s due—briefly, like a nod to a well-dressed con artist. On paper, NGPA slices through RA 9184‘s opacity like a katana through butter. The killer feature? Sections 81 and 82, mandating that bidders cough up beneficial ownership (BO) information: the natural persons who “ultimately own or dominantly influence the management or policies” of the bidding entity (Section 4(b)). No more faceless shell companies; disclose your puppet masters or get the boot. This feeds into a public registry run by the GPPB (Section 82), where data gets splashed online for all to scrutinize—echoing open contracting principles in the Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR), Section 3.3. And the blacklisting? Oh, it’s vicious: Sections 102–105 extend suspensions not just to the corporate front, but to its beneficial owners and any entity they control (Section 105). False disclosures? Automatic disqualification and a one-to-two-year blacklist under Section 100(g), plus forfeiture of bid securities. It’s a genuine upgrade from RA 9184‘s toothless nods to “collusion” (like its vague bid-rigging clauses), where ownership was a black box and penalties stopped at slaps on the wrist.

But here’s the pivot, the surgical twist of the knife: Disclosure ain’t verification, sweetheart. NGPA demands the truth but doesn’t arm enforcers to hunt it down. Where’s the mandatory cross-check against Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) records, Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) tax filings, or Anti-Money Laundering Council (AMLC) suspicious transaction reports? Section 23 babbles about “interconnectivity” for the GPPB registry, but it’s aspirational fluff—no teeth, no timelines, no budget line item. What stops a syndicate from layering ownership through Cayman trusts, compliant nominees, or offshore daisy chains? A well-heeled crook with a Rolodex of lawyers can declare a “clean” BO—a distant cousin with a spotless rap sheet—while the real strings get pulled from a Singapore safe deposit box. It’s transparency theater: Everyone sees the script, but the director’s still calling shots from the shadows. RA 9184 didn’t even pretend at BO definitions; NGPA does, but without verification muscle, it’s just a prettier invitation to the same old grift.

Ghosts of Scandals Past: The Classics That NGPA Pretends to Bury

To appreciate NGPA‘s “revolution,” revisit the greatest hits of procurement perversion under RA 9184—those low-risk, high-reward romps that turned public funds into private jets. Palit-pangalan (name-swapping) and palit-ulo (head-swapping)? Bidders rebranded shells to fake competition, violating Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act (RA 3019), Section 3(e) (manifest partiality causing undue injury) and Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees (RA 6713), Section 4(a) (public interest betrayal). Dummy bidders? Relatives fronting for officials, breaching RA 3019 Section 3(h) (pecuniary interests) and RA 6713 Section 7(a) (financial conflicts). Bid-splitting? Chopping megaprojects into mouse-sized contracts to dodge open bidding, as in the Sandiganbayan’s People v. Combista (2021), flouting RA 3019 Section 3(g) (disadvantageous contracts) and RA 9184‘s competitive mandates.

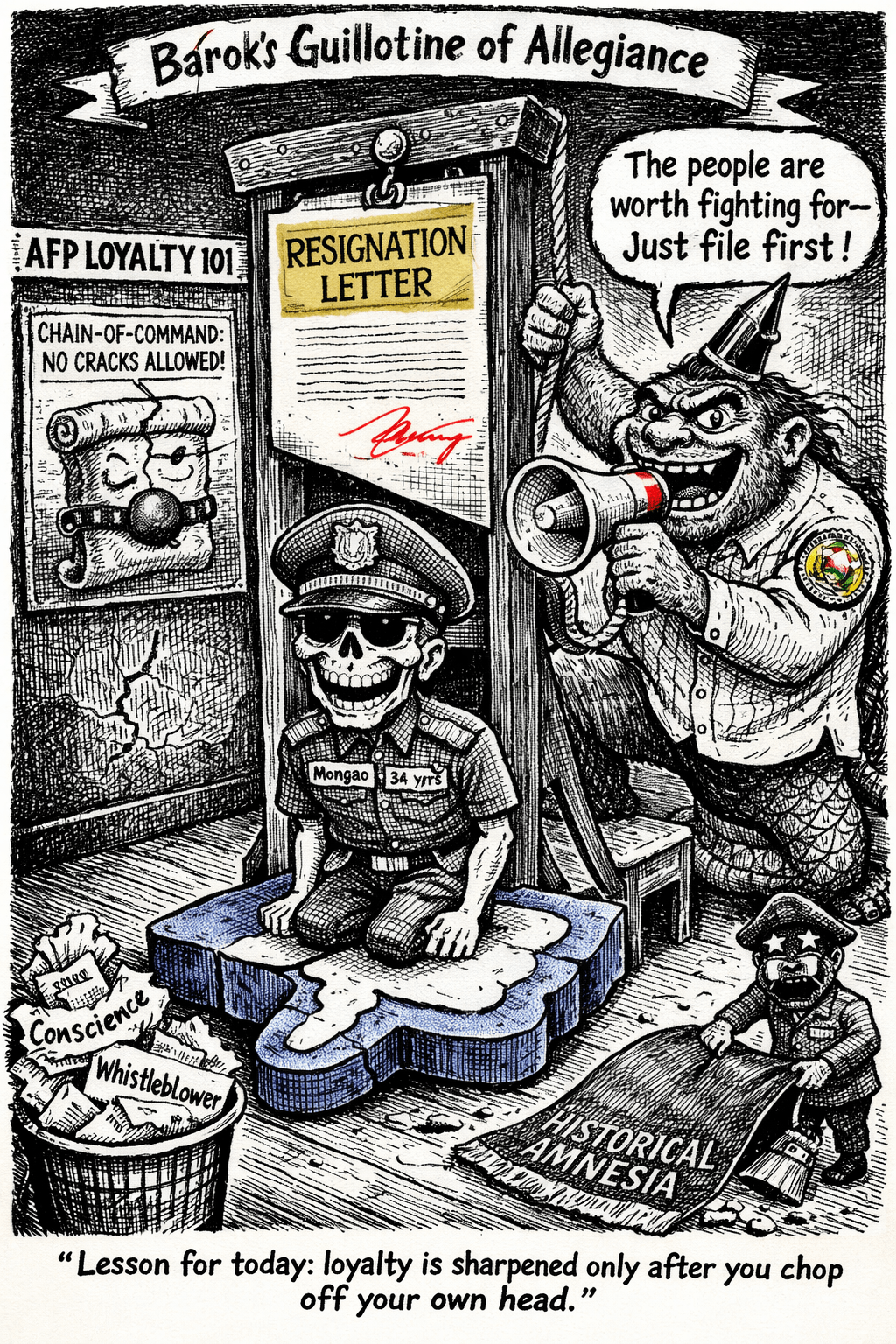

Collusive related bidding? That 65.8% overlap in owners, coordinating “losses” to the pre-chosen winner—pure RA 3019 Section 3(e) bad faith. These weren’t prosecutable felonies; they were Tuesday afternoons. Why? Supreme Court precedents like the 2024 ruling in Navales v. People (G.R. Nos. 219598 & 220108, August 7 2024) set the bar sky-high: Procurement glitches don’t auto-equate to graft without ironclad proof of “bad faith” or “manifest partiality” under RA 3019 Section 3(e). In Martel v. People (G.R. Nos. 224765-68, 2021), the Court nailed officials for rigging hospital equipment bids, but only because the paper trail of overpriced ventilators was thicker than a congressman’s wallet. Absent that? Acquittals galore. RA 6713‘s ethical guardrails (e.g., Section 7(d) banning solicitation) gathered dust, because who prosecutes a “technical violation” when the Office of the Ombudsman‘s inbox overflows with pols’ golf buddies?

The Whack-a-Mole Theory: Corruption’s Next Act in the NGPA Theater

DBM’s narrative? Adorable. As if crooks read press releases and retire to Baguio. Corruption isn’t a static beast; it’s a hydra—chop one head, and three nominees pop up. NGPA plugs old holes, but watch the moles burrow new ones, grounded in the law’s own cracks and our jurisprudence’s leniency.

First, the Impenetrable Nominee: Declare a squeaky-clean BO—a retiree auntie with no SEC flags—and layer the control through trusts or “advisory” fees. Section 81 demands disclosure, but without AMLC-mandated probes, it’s self-reported honor system. Per RA 3019 precedents, proving the lie requires “evident bad faith”—good luck with that in a system where People v. Montejo let proxies slide for “lack of intent.”

Then, the Procedural Bypass: NGPA‘s 11 shiny modalities (e.g., negotiated contracts under Section 29, emergency modes in Section 35) scream flexibility, but whisper “loophole.” Classify a routine bridge repair as “unsolicited with bid matching” (Section 30) to skip open bidding and BO disclosures entirely. RA 9184’s exceptions were abused for overpriced PPE; NGPA‘s “fit-for-purpose” (Section 26) is subjective catnip for Bids and Awards Committee (BAC) cronies, evading RA 6713‘s justness pledge (Section 4(c)) with a wink.

Post-award? The real feast. Shift the shakedown to change orders (Section 92(c) tweaks, anyone?), inferior deliveries, or warranty fraud—phases where NGPA‘s oversight thins like watered-down adobo. Collude with the BAC to rubber-stamp fudged docs, betting on RA 3019‘s intent hurdle: No “dishonest gain” proven? No cuffs, as in those 2024 SC acquittals for “mere irregularities.”

Insider enablers seal it: BAC collusion to ignore red flags, falsifying analytics under Section 24. It’s RA 3019 Section 3(b) bribery in slow motion, but prosecutable? Only if the stars align and the Ombudsman skips siesta.

Verdict: Tools for Titans, Wielded by Dwarves

Pangandaman’s not wrong—NGPA’s a toolbox sharper than RA 9184‘s rusty pliers. But it’s dangerously naive to hand it to the same broken system: understaffed BACs, siloed agencies, and a judiciary that treats graft like a parking ticket. The law’s potential drowns in execution’s swamp.

Non-negotiable fixes? First, the IRR must birth a mandatory, interoperable BO verification engine—SEC, BIR, AMLC data-sharing on steroids, with API hooks and audit trails. No more “transition period” excuses (that three-year grace from standard forms). Second, weaponize administrative deterrence: NGPA‘s blacklisting (Sections 102–105) has a lower bar than RA 3019‘s criminal gauntlet—slap suspensions like confetti, no “bad faith” needed. Third, draw first blood: The NGPA‘s baptism must be high-profile—name-and-shame blacklistings of a senator’s dummy or a mayor’s crony, followed by Ombudsman prosecutions livestreamed for the nation. Make examples that echo Martel’s convictions for fleecing hospital budgets, not Navales‘ shrugs.

The law is on the books. Now prove it’s not just another piece of paper for the archives. DBM, media watchdogs, civil society: Your move. Fail, and we’ll all be back here in 2028, mocking NGPA 2.0. Because in Philippine procurement, hope is eternal—tragically so.

Key Citations

- Cabato, Luisa. “DBM to Bidders: Shady Schemes Won’t Work under New Procurement Law.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 20 Oct. 2025.

- Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees. Republic Act No. 6713, 20 Feb. 1989.

- Republic of the Philippines. Republic Act No. 3019: Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. Official Gazette, 17 Aug. 1960.

- Government Procurement Reform Act. Republic Act No. 9184, 10 Jan. 2003.

- New Government Procurement Act. Republic Act No. 12009, 20 July 2024.

- Republic of the Philippines. Implementing Rules and Regulations of Republic Act No. 12009: New Government Procurement Act. Government Procurement Policy Board, 12 Aug. 2025.

- Government Procurement Policy Board – Technical Support Office. GPPB Resolution No. 07-2023. Government Procurement Policy Board, 23 Aug. 2023. Accessed 21 Oct. 2025

- People v. Combista. Sandiganbayan, 2021.

- Martel v. People. G.R. Nos. 224765-68, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 2 Oct. 2021,

- Republic of the Philippines, Supreme Court. Arnold D. Navales, Rey C. Chavez, Rosindo J. Almonte, Alfonso E. Laid, and William Velasco Guillen v. People of the Philippines, G.R. Nos. 219598 and 220108, 7 Aug. 2024, LawPhil. Accessed 21 Oct. 2025.

- “Pork barrel scam.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 13 Oct. 2025. Accessed 21 Oct. 2025.

- “What COA flagged in DOH’s handling of billions in COVID-19 funds.” Philippine Star, 11 Aug. 2021.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

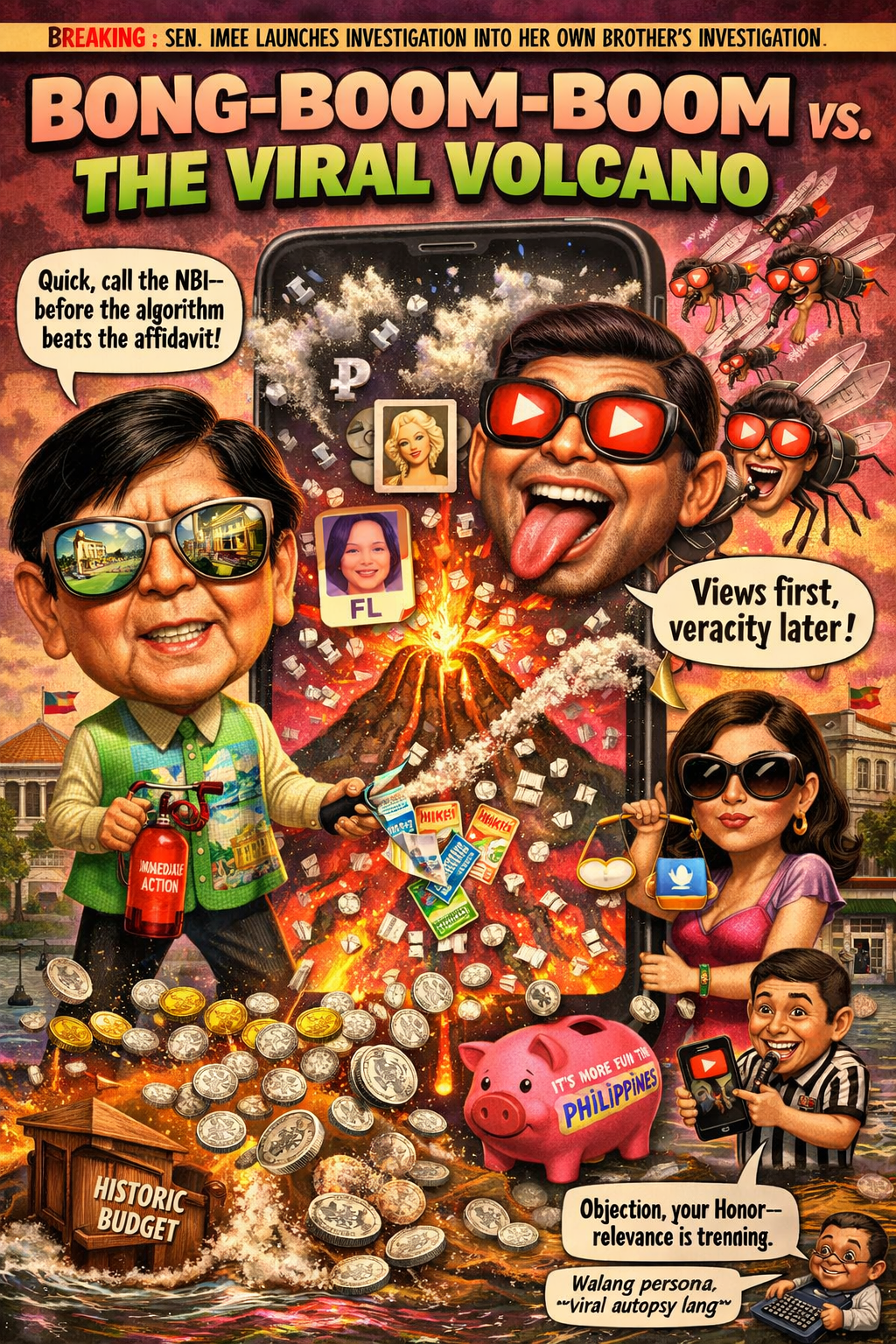

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

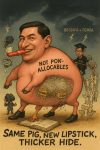

- “Allocables”: The New Face of Pork, Thicker Than a Politician’s Hide

- “Ako ’To, Ading—Pass the Shabu and the DNA Kit”

Leave a comment