A Crony Carnival Before the Exit: Martires’s Last-Minute Hiring Spree

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — October 25, 2025

BRACE for impact, scandal fans! The Office of the Ombudsman is dishing out a controversy so spicy it could set your screen ablaze. The plot thickens as incoming Ombudsman Jesus Crispin “Boying” Remulla wields his reformer’s scalpel, slicing through the institutional rot left by his predecessor, Samuel Martires. At the heart of this drama? A brazen hiring spree that reeks of cronyism, with Martires’s “anointed ones” parachuted into cushy, director-level posts just before his retirement curtain call. Let’s unpack this legal and ethical dumpster fire, with a generous dose of sarcasm and a firm grip on the law, to show why Martires’s midnight maneuvers deserve a takedown and why Remulla’s response—while not flawless—is a necessary purge to save the Ombudsman’s soul.

Martires’s Last Hurrah: A Hiring Spree to Haunt the Halls

Picture this: it’s July 2025, and Samuel Martires, with one foot out the Ombudsman’s door, decides to play Santa Claus to a select group of loyalists. In a move that shocked no one with a pulse, he sprinkles 204 new hires across the agency, many clutching freshly printed law degrees and landing in Salary Grade (SG) 26 and 27 posts—director-level gigs paying a cool P126,252 to P158,723 a month, per the Department of Budget and Management’s (DBM) National Budget Circular No. 594. These aren’t grizzled veterans but “newly minted lawyers,” as Remulla rightly scoffed in his ANC interview, promoted to ranks that make career staff choke on their coffee.

Let’s call it what it is: a midnight appointment spree, executed with the finesse of a sledgehammer. The Ombudsman Act (Republic Act No. 6770), Section 11, gives the Ombudsman power to appoint staff “in accordance with the Civil Service Law,” but Martires seems to have read that as “anoint whoever you fancy.” The Civil Service Commission’s (CSC) 2017 Omnibus Rules on Appointments and Other Human Resource Actions (ORAOHRA), Rule IV, demands merit and fitness, with positions tied to strict qualification standards. Yet, Martires’s legal prodigies, barely out of bar review, waltzed into director-level roles, sidestepping the grizzled careerists who’ve been grinding for years. This isn’t just bad management; it’s an ethical betrayal under Republic Act No. 6713 (Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials), Section 4(b), which mandates “justness and sincerity” in public service. Instead, Martires gifted his allies golden parachutes, leaving morale in tatters and the Ombudsman’s integrity dangling by a thread.

The timing screams intent. These hires, concentrated in the months before Martires’s July 27, 2025, retirement, echo the “midnight appointments” condemned in Aytona v. Castillo (G.R. No. L-19313, January 19, 1962), where the Supreme Court struck down 350 last-minute appointments as a “studied effort” to entrench loyalists. While Article VII, Section 15 of the 1987 Constitution targets presidential appointments, the principle—abusing power to stack an agency with cronies—applies here in spirit. Martires’s spree wasn’t just a farewell party; it was a calculated move to sabotage his successor, planting loyalists like landmines to undermine the Ombudsman’s independence under RA 6770, Section 5.

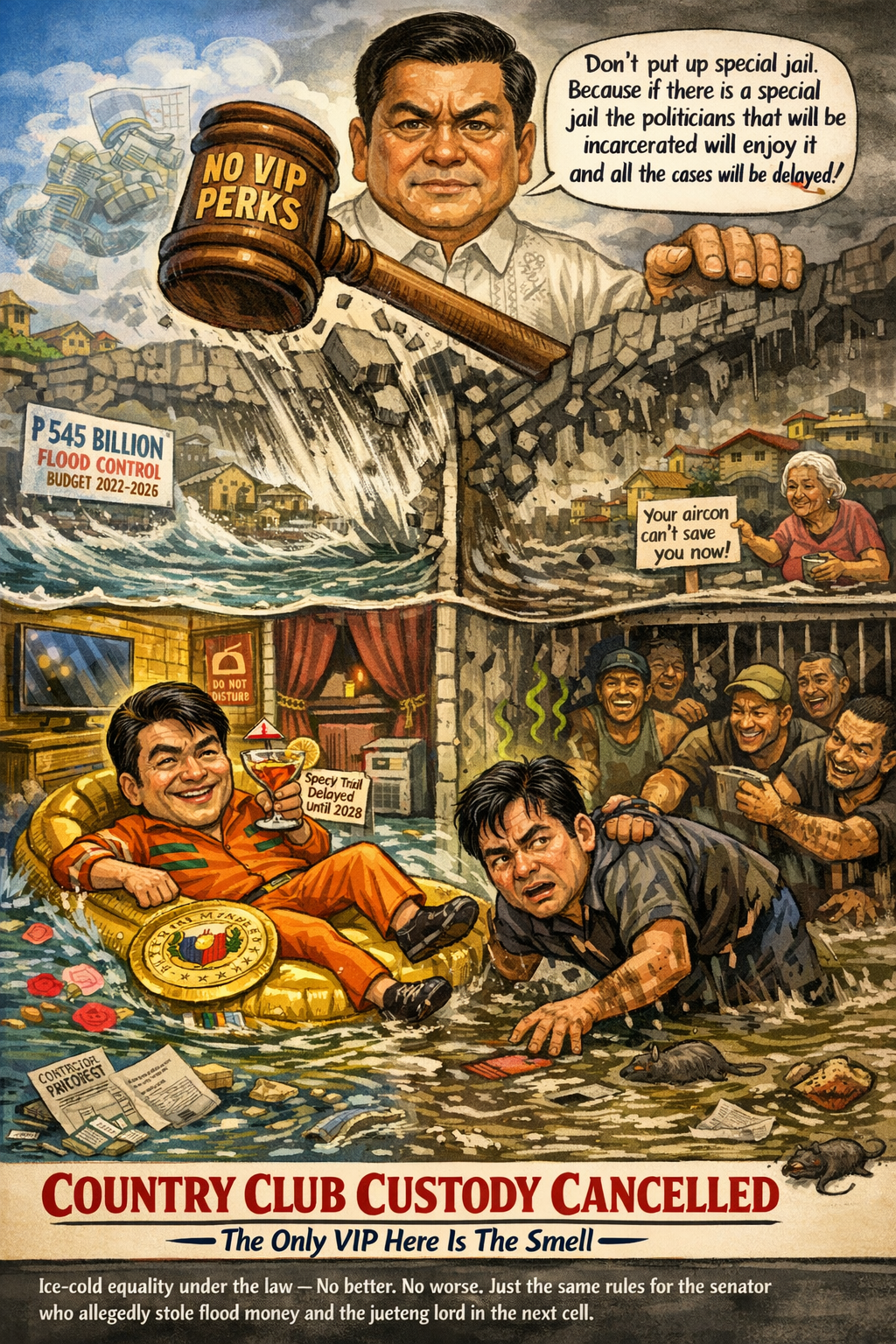

Remulla’s Surgical Strike: A Reformer’s Gambit

Enter Boying Remulla, the new sheriff in town, who’s not here to play nice with Martires’s parting gifts. In a move that’s equal parts bold and controversial, Remulla demanded courtesy resignations from all 204 appointees, with 99 holding SG 25 and above, and asked them to reapply, as reported by Philstar.com. Cue the gasps from the peanut gallery, but let’s break it down: this is no purge for purge’s sake. It’s a calculated strike to restore meritocracy and protect the Ombudsman’s soul.

Under RA 6770, Section 11, Remulla has the authority to shape his team, appointing staff “in accordance with the Civil Service Law.” He’s not just flexing muscle; he’s exercising a legitimate managerial prerogative to vet his team for an office tasked with rooting out graft. As he told ANC, “It’s bad for morale when you bring in people who are less qualified than those who are already in the service” (Philstar.com). Damn right, Boying. When fresh-faced lawyers leapfrog over seasoned prosecutors into director-level posts, it’s a slap in the face to the career staff who’ve been slogging through corruption probes. RA 6713, Section 4(a), demands “utmost responsibility, integrity, and efficiency,” and Remulla’s move aligns with that mandate, ensuring his team is fit for the high-stakes anti-graft arena.

Critics will cry foul, whining about operational disruption or accusing Remulla of a Marcos-fueled vendetta against Duterte loyalists. Sure, asking 204 people—over 10% of the Ombudsman’s roughly 2,000 staff—to reapply could slow down cases, especially high-profile ones like Vice President Sara Duterte’s alleged fund misuse. And yes, the optics of a Marcos ally targeting Duterte-era hires raise eyebrows, especially given reports of political tensions. But let’s dismantle these gripes: the greater good here is institutional integrity. If Remulla lets Martires’s cronies fester, the Ombudsman risks becoming a patronage playground, eroding public trust and violating RA 6770‘s mandate for independence. A temporary hiccup in operations pales against the long-term rot of favoritism. As for the vendetta charge, Remulla’s broader reforms—like lifting Martires’s SALN restrictions—show a commitment to transparency, not politics, per RA 6713, Section 8.

The Legal Noose Tightens: Why Martires’s Moves Don’t Pass Muster

Let’s get nerdy with the law, because Martires’s stunt doesn’t just stink—it’s legally shaky. The CSC’s ORAOHRA, Rule VII, ties promotions to performance and qualifications, not loyalty oaths. Assigning SG 26/27 to novices likely violates Executive Order No. 292 (Administrative Code of 1987), Book V, Title I, Subtitle A, Chapter 5, which demands “merit and fitness” through competitive processes or equivalents like bar passage. If these hires lacked the requisite experience—say, the seven years typically required for director-level posts under DBM guidelines—they’re not just ethically dubious; they’re potentially voidable under CSC rules for improper classification.

Then there’s the midnight appointment analogy, and oh, does it sting. While Article VII, Section 15 of the 1987 Constitution slaps a ban on presidential appointments, the spirit of Aytona v. Castillo (G.R. No. L-19313, January 19, 1962)—condemning last-minute hires to entrench loyalists—haunts Martires’s pre-retirement spree like a vengeful ghost. His eleventh-hour push to parachute 204 allies into cushy posts reeks of the same bad faith that got Executive Order No. 2 (2010) to clean house under Aquino. If Remulla’s audit (which he better order yesterday) shows these hires lack proper plantilla, funding, or qualifications, they’re toast—void ab initio under the Civil Service Commission’s ORAOHRA, Rule XI.

Remulla’s Tightrope: Navigating the Legal and Ethical Minefield

Remulla’s not out of the woods yet. His courtesy resignation gambit, while bold, treads on thin ice. Forcing career civil servants—protected by Article IX-B, Section 2(3) of the Constitution, which guarantees tenure except for cause—to resign risks violating due process. Luego v. Civil Service Commission (G.R. No. L-69137, August 5, 1986) is crystal clear: valid appointments can’t be revoked arbitrarily. If Martires’s hires met CSC eligibility (e.g., bar passage for lawyers), Remulla’s blanket order could spark lawsuits, with affected employees seeking injunctions or backpay. The CSC has warned against coercive resignations, and a court could deem Remulla’s approach void if it smells of retaliation.

But here’s the kicker: Remulla can sidestep this trap. Instead of strong-arming resignations, he should order an immediate audit of appointment papers, plantilla, and qualifications, per RA 6770 and CSC rules. If irregularities surface—say, fake positions or misclassified salaries—he can rescind them with due process, giving notice and a chance to respond. If the hires are legit but underqualified, he can reassign them to lower roles or mandate training, aligning with RA 6713’s value development (Section 12). This avoids the legal quagmire while reinforcing meritocracy.

The Fallout: A Precedent for Chaos or Reform?

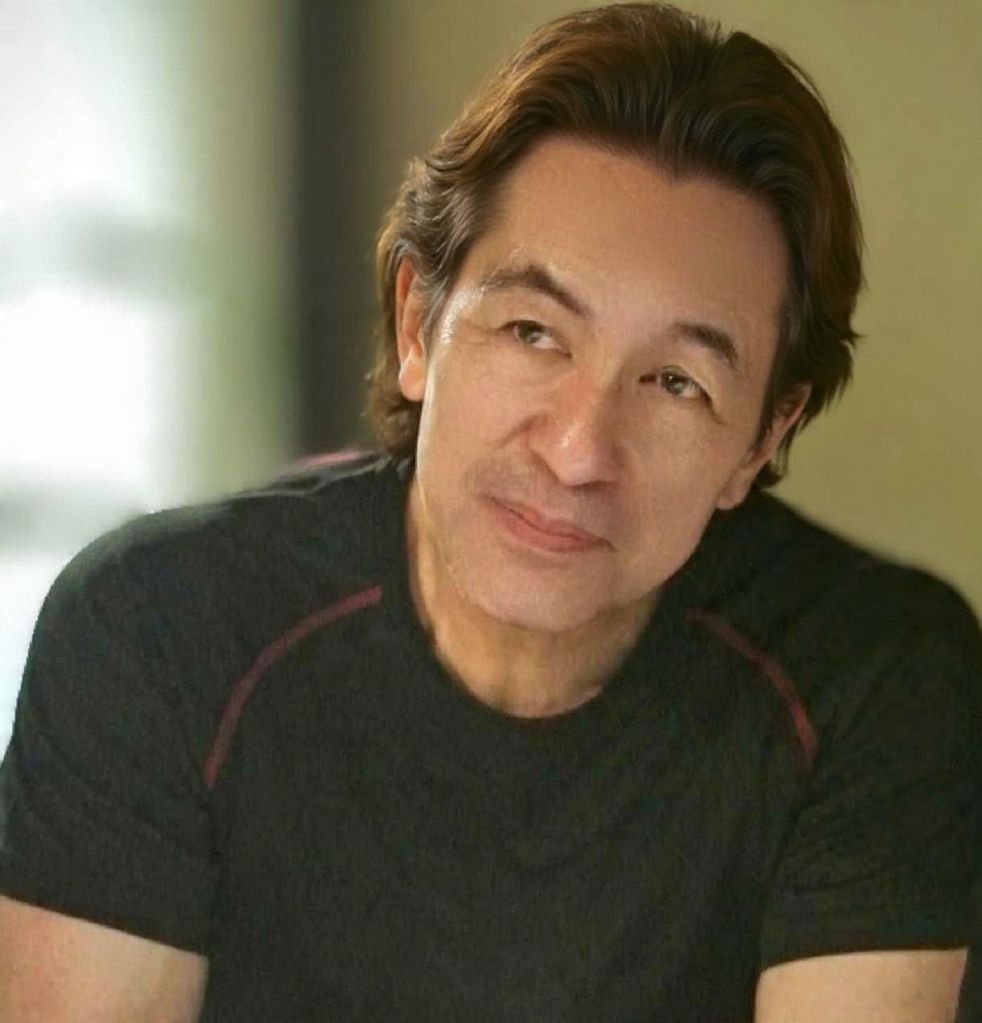

This saga’s ripples go beyond the Ombudsman’s walls. Left unchecked, Martires’s hires set a precedent for outgoing officials to stack agencies with loyalists, turning civil service into a patronage pinata. The Ombudsman’s credibility—already battered by Martires’s SALN secrecy—takes another hit, eroding public trust in an office meant to fight corruption. Career staff, demoralized by leapfrogging newbies, might jump ship, leaving probes like Sara Duterte’s fund case in limbo. Politically, this fuels the Marcos-Duterte feud, with Remulla’s moves framed as a purge of Duterte allies, potentially igniting 2028 election tensions.

Yet, if Remulla plays it smart—transparent audits, non-coercive vetting, and merit-based rehiring—he could turn this mess into a masterclass in reform. A cleaned-up Ombudsman, free of crony taint, would strengthen anti-graft efforts and restore public faith. The CSC and DBM should back him, ensuring compliance with ORAOHRA and National Budget Circulars. Failure to act, though, risks lawsuits, operational paralysis, and a legacy of politicization that could haunt the civil service for years.

The Final Word: Remulla’s Redemption or Martires’s Revenge?

The Ombudsman’s office isn’t a playground for political favors—it’s the nation’s anti-corruption watchdog, and Martires’s midnight hires were a betrayal of that mandate. Remulla, for all the risks, is right to wield the broom, provided he does so with legal precision and ethical clarity. This isn’t just a staffing spat; it’s a battle for the Ombudsman’s soul. By rooting out cronyism and restoring meritocracy, Remulla can cement his legacy as a reformer—or, if he fumbles, hand Martires’s ghost a posthumous victory. The legal noose is tightening, and the nation’s watching. Choose wisely, Boying.

Key Citations:

- Philstar.com: Some ‘new hires’ in Ombudsman already in high salary grade — Remulla

- Philippines. 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines. Official Gazette, 1987. Accessed 25 Oct. 2025.

- Republic Act No. 6770 (Ombudsman Act of 1989), Sections 5, 11, 13

- Republic Act No. 6713 (Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards), Sections 4, 8, 12

- Civil Service Commission, 2017 Omnibus Rules on Appointments and Other Human Resource Actions (ORAOHRA), Rules IV, VII, XI (available via CSC official site or government records)

- Executive Order No. 292 (Administrative Code of 1987), Book V, Title I, Subtitle A, Chapter 5

- Aytona v. Castillo, G.R. No. L-19313, January 19, 1962

- Luego v. Civil Service Commission. G.R. No. L-69137, 5 Aug. 1986. Accessed 25 Oct. 2025.

- Department of Budget and Management, National Budget Circular No. 594

- “Executive Order No. 2, s. 2010: Directing All Department Secretaries and Heads of Agencies to Conduct a Review of All Appointments and Hiring Made from May 10, 2010 to June 30, 2010.” Official Gazette, Office of the President of the Philippines, 30 July 2010.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

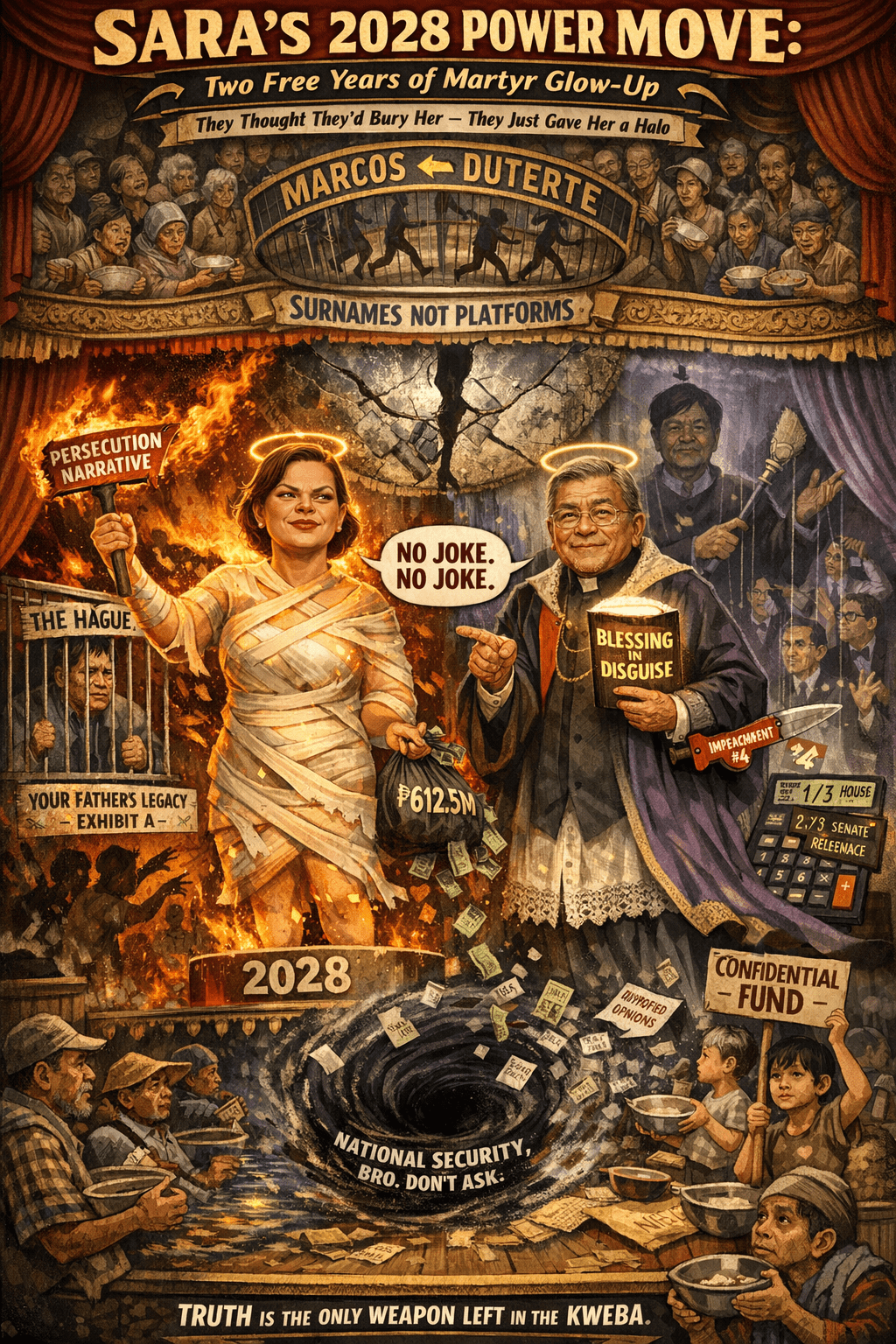

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

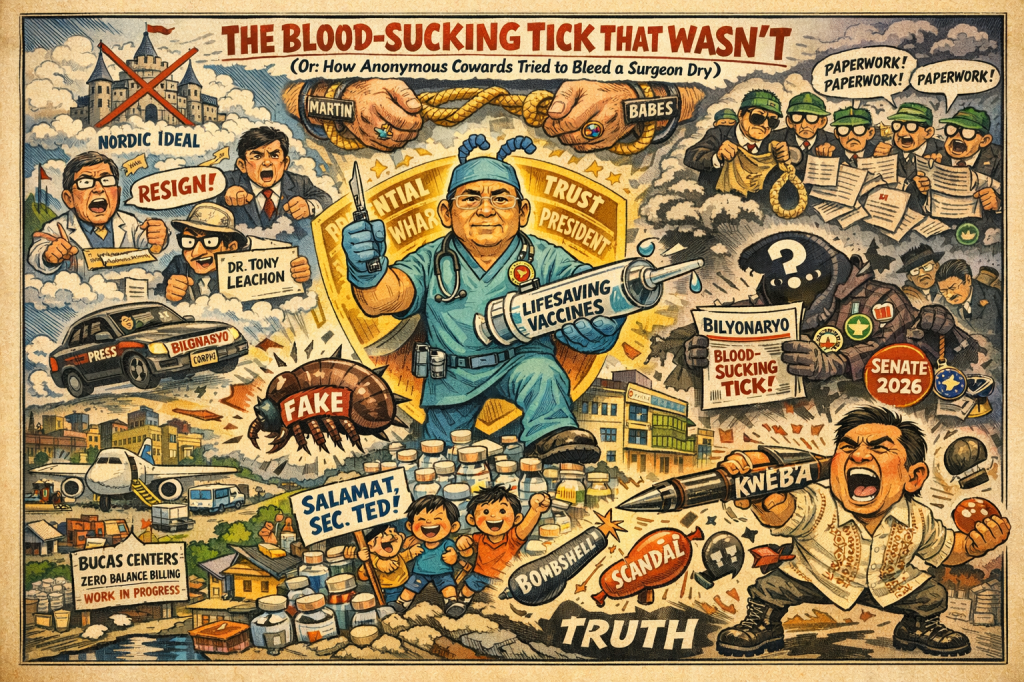

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

Leave a comment