The Art of Leaving Quietly — and Taking the Furniture With You

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — October 30, 2025

1. The Grand Exit: How to Burnish Your Legacy by Burying It Under Paperwork

When ordinary civil servants retire, they take home a clock and a cake.

When former Ombudsman Samuel Martires retired in July 2025, he left something more enduring: 204 freshly hired and newly promoted personnel, all processed within his final three months.

In his own defense, Martires told GMA News there were “no midnight appointees” because the Ombudsman’s Office “is not a political office.” Translation: I’m apolitical, therefore unaccountable.

But politics is not a virus you can vaccinate against with good intentions. When an outgoing official floods an institution with last-minute hires, the issue isn’t partisanship — it’s power. And power, in the Philippine bureaucracy, tends to outlive its wielder.

2. The Legal Smackdown: When ‘We’re Not Political’ Becomes a Legal Alibi

Martires’s favorite shield is the claim that Article VII, Section 15 of the 1987 Constitution — which bans “midnight appointments” two months before a President’s term ends — applies only to Malacañang, not to him. Technically, he’s right: the Constitution names the President.

But law is not a game of “catch-me-if-you-can.” The Supreme Court’s ruling in Aytona v. Castillo (G.R. No. L-19313, Jan. 19, 1962) made clear that midnight appointments are “anathema to orderly governance.” The Court didn’t say “Presidential midnight appointments,” it said midnight appointments. The spirit of that decision — that no public officer should tie the hands of his successor through a last-minute personnel blitz — applies with equal force to every constitutional body that claims independence.

So unless Martires believes he inhabits a legal vacuum, his defense collapses on contact with principle. The Office of the Ombudsman is a constitutional creation (Article XI), not a private law firm. Its independence is meant to protect it from capture, not to justify self-capture.

3. The Procedural Farce: A Blow-by-Blow of How ‘Compliance’ Dies Under the Weight of Reason

Martires says he followed procedure:

- Asked the Department of Budget and Management (DBM) in August 2024 to approve 60 new lawyer positions.

- DBM signed off in January 2025.

- Job openings were published through the Civil Service Commission (CSC).

- He filled the slots — plus 144 other plantilla positions — before riding into the sunset in July.

If compliance were the sole measure of propriety, every thief with a receipt would be a merchant. Bureaucratic formality is not the same as legitimacy.

Consider timing: between May and July 2025, a three-month personnel blitzkrieg hit the Office of the Ombudsman. Two hundred and four hires and promotions — in a period when the outgoing head already knew his term’s sandglass was nearly empty. That’s not “institutional efficiency”; that’s administrative embalming.

The Supreme Court has long warned against such last-minute staffing sprees. In In Re: Appointments Dated March 30, 1998 (G.R. No. 132877, Apr. 24, 1998), the Court voided judicial appointments made during an election ban because they “defeat the orderly transfer of authority.” The Ombudsman may not be the President, but the logic applies: late-term appointments are inherently suspect when they pre-empt a successor’s discretion.

Procedural compliance, then, becomes a fig leaf. A DBM approval and a CSC posting may check the administrative boxes, but they cannot launder intent. The law cares not only for what you do but when and why you do it.

4. The For-and-Against Evisceration: Martires’s Defense, Stripped and Cross-Examined

Martires argues that the hires were necessary, efficient, and procedurally sound.

That’s the bureaucrat’s holy trinity — the last refuge of those who mistake compliance for integrity.

Let’s take them one by one:

Necessity? Martires claims the hiring binge was needed to “speed up case resolution” by merging the fact-finding and preliminary investigation units. Noble, except for one detail: if this structural reform was so urgent, why did it materialize only during the last quarter of his term? The Office of the Ombudsman had six years to rationalize its internal processes. Suddenly, in the twilight of his tenure, Martires discovered administrative salvation — conveniently through 204 appointments. How inspiring.

Efficiency? True efficiency in governance isn’t about filling seats — it’s about accountability, transparency, and results. The Ombudsman’s docket backlog has persisted through multiple administrations, not for lack of personnel but for lack of political will. Doubling the staff in your final months doesn’t streamline the process; it entrenches loyalties. It’s the bureaucratic equivalent of leaving banana peels on your successor’s floor.

Procedural compliance? Martires flaunts DBM approval and CSC publication as if those two stamps absolve timing, motive, and ethics. But even procedurally perfect acts can still violate the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees (Republic Act No. 6713), which condemns not only corruption but the “appearance of impropriety.” You can’t hide moral rot under paperwork.

The Supreme Court itself, in Aytona, warned that “appointments made in haste and under suspicious circumstances” deserve heightened scrutiny. The Ombudsman is not immune to that wisdom. His oath is to fight corruption, not to redefine it as administrative housekeeping.

5. The Consequence Cascade: When the Watchdog Becomes the Wolf’s Heir

Every institutional scandal leaves collateral damage. This one threatens to corrode the very office meant to guard against corruption.

By planting 204 new hires during his exit, Martires effectively handcuffed his successor, Ombudsman Jesus Crispin Remulla, who must now manage an office partially loyal to his predecessor. The risk isn’t just inefficiency; it’s institutional capture. In the culture of Philippine bureaucracy — where promotions, assignments, and perks often align with patronage — such hires form a durable network of allegiance.

The result? A weakened Ombudsman whose independence now exists more in theory than in practice. The nation’s anti-graft watchdog starts to look like a Frankenstein’s monster of civil service appointments, stitched together by one man’s departing ambition.

Worse, the scandal threatens the credibility of the very investigations the Ombudsman undertakes. How can the public trust a graft-busting office whose last act under Martires resembles the very thing it prosecutes — the abuse of official discretion?

Legally, these appointments could still be challenged. Under the Ombudsman Act of 1989 (Republic Act No. 6770), the Ombudsman wields broad administrative powers, but those powers are still subject to the Constitution and the principle of good governance. The Civil Service Commission may review questionable appointments under its oversight of merit and fitness. And if Ombudsman Remulla moves to invalidate them, the courts — citing Aytona and In Re: Appointments Dated March 30, 1998 — may have to decide whether Martires’s “parting gift” was a legal act or a constitutional trespass.

6. The Road to Resolution: Purge, Appeal, or Pretend Nothing Happened?

Remulla now faces a bureaucratic minefield. His choices are ugly:

Option 1: Purge the questionable appointees.

Legally clean, politically explosive. This move would assert institutional integrity but trigger protests, administrative cases, and maybe a few “unfair labor practice” headlines. Yet if the Ombudsman is to reclaim moral authority, this is the path that most aligns with both Aytona and Republic Act No. 6713.

Option 2: Let the courts decide.

A safer bet, but also the most cynical. In a judiciary already besieged by case backlogs, a petition for declaratory relief could drag on for years. By then, the appointees would be entrenched, their permanence making reversal nearly impossible. In other words: delay is victory.

Option 3: Do nothing.

The most Filipino solution of all. Pretend the controversy never happened, talk vaguely about “healing” and “moving forward,” and wait for the news cycle to move on. But inaction is itself a choice — one that normalizes ethical decay and signals to future Ombudsmen that midnight appointments are fair game so long as they’re made before sunrise.

7. Final Verdict: The Ombudsman Who Couldn’t Resist Being His Own Exhibit A

In the end, Martires’s defense is as thin as the ink on his appointment papers. His claim of “non-political” status is a straw man; his appeal to procedure, a smokescreen; his timing, a confession.

The Office of the Ombudsman exists to ensure that no public officer uses position for private ends. By orchestrating a last-minute personnel surge, Martires didn’t just stretch the rules — he redefined them in his own image. His exit strategy wasn’t a farewell; it was a hostile takeover disguised as reform.

For an institution built on moral rectitude, this episode is nothing less than a constitutional farce — a case study in how legality can be weaponized against ethics. The next time the Ombudsman lectures the public about corruption, remember this moment: when the watchdog, on his way out the gate, quietly handed the keys to 204 new friends.

The lesson for future Ombudsmen — and for the nation — is brutal in its simplicity: the rule of law is only as strong as the conscience of those who wield it. And in Martires’s twilight, conscience seems to have retired early.

Key Citations

- “Martires Denies Making Midnight Appointments.” GMA Network, GMA News Online. Accessed 29 Oct. 2025.

- Philippines. 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines. Official Gazette, 1987. Accessed 29 Oct. 2025.

- Aytona v. Castillo, G.R. No. L-19313, January 19, 1962.

- Republic Act No. 6713 (Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards),

- Republic Act No. 3019. Official Gazette, 17 Aug. 1960.

- Republic Act No. 6770. The Ombudsman Act of 1989. 17 Nov. 1989.

- “In Re: Appointments dated March 30, 1998 of Hon. Mateo A. Valenzuela and Hon. Placido B. Vallarta.” A.M. No. 98-5-01-S.C., 9 Nov. 1998. LawPhil.

- Atty. Bulao. “Landmark Cases on Midnight Appointments (Aytona vs. Castillo).” AttyBulao Blog, 10 May 2011.

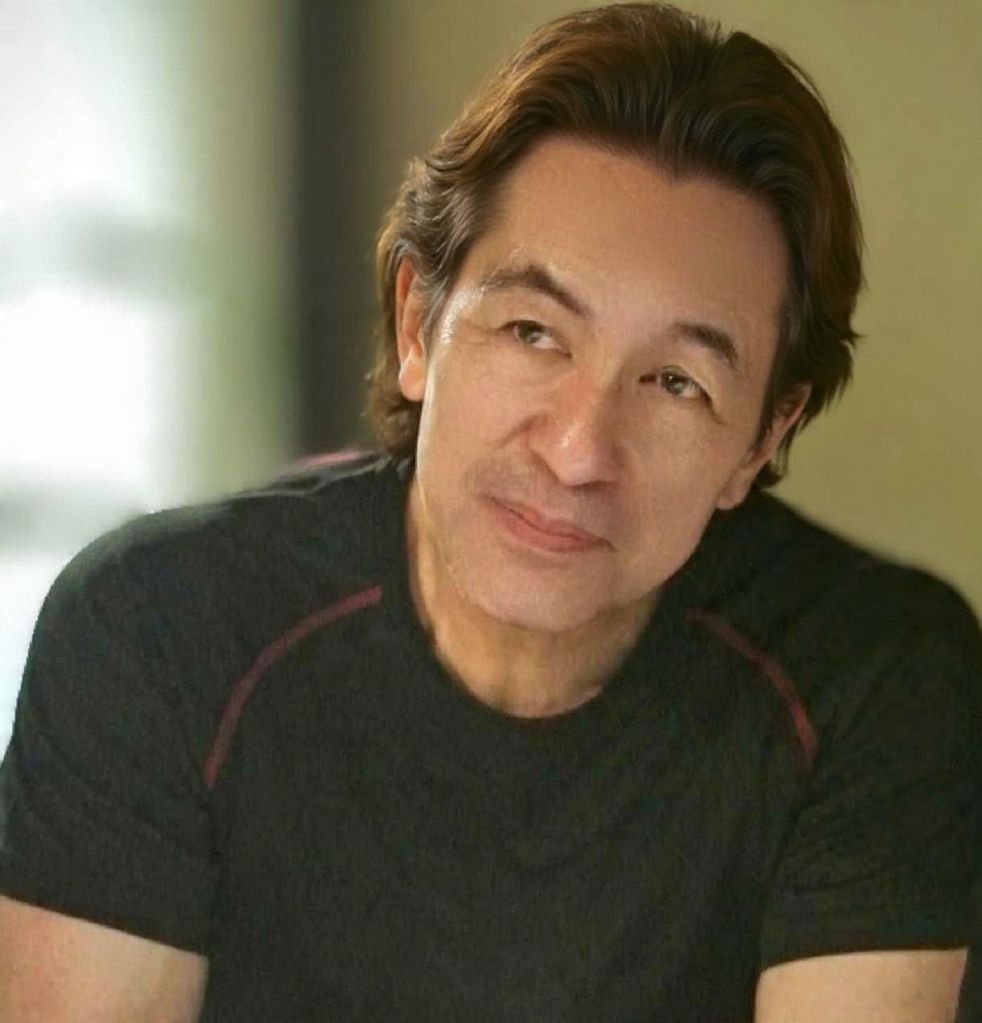

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

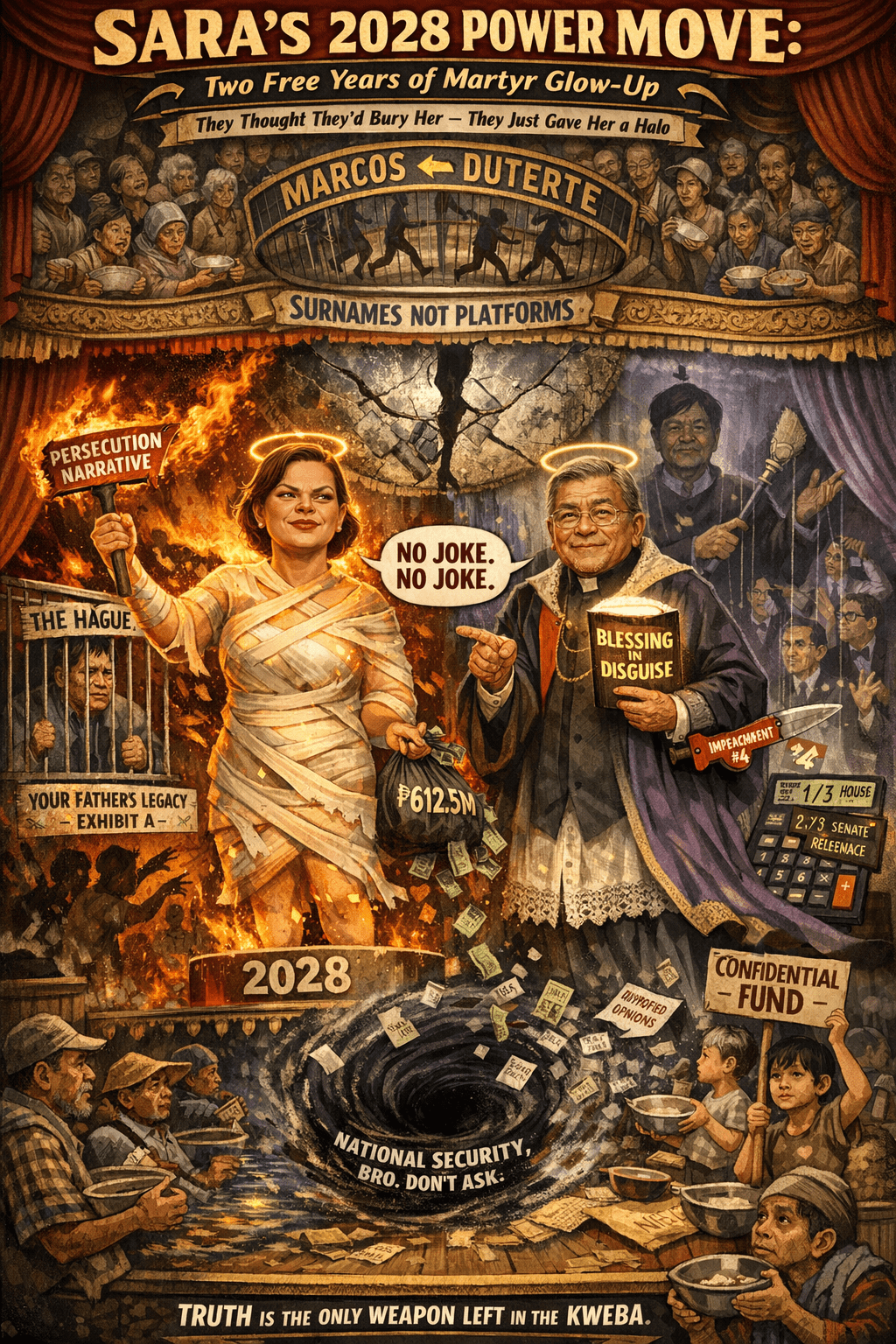

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

Leave a comment