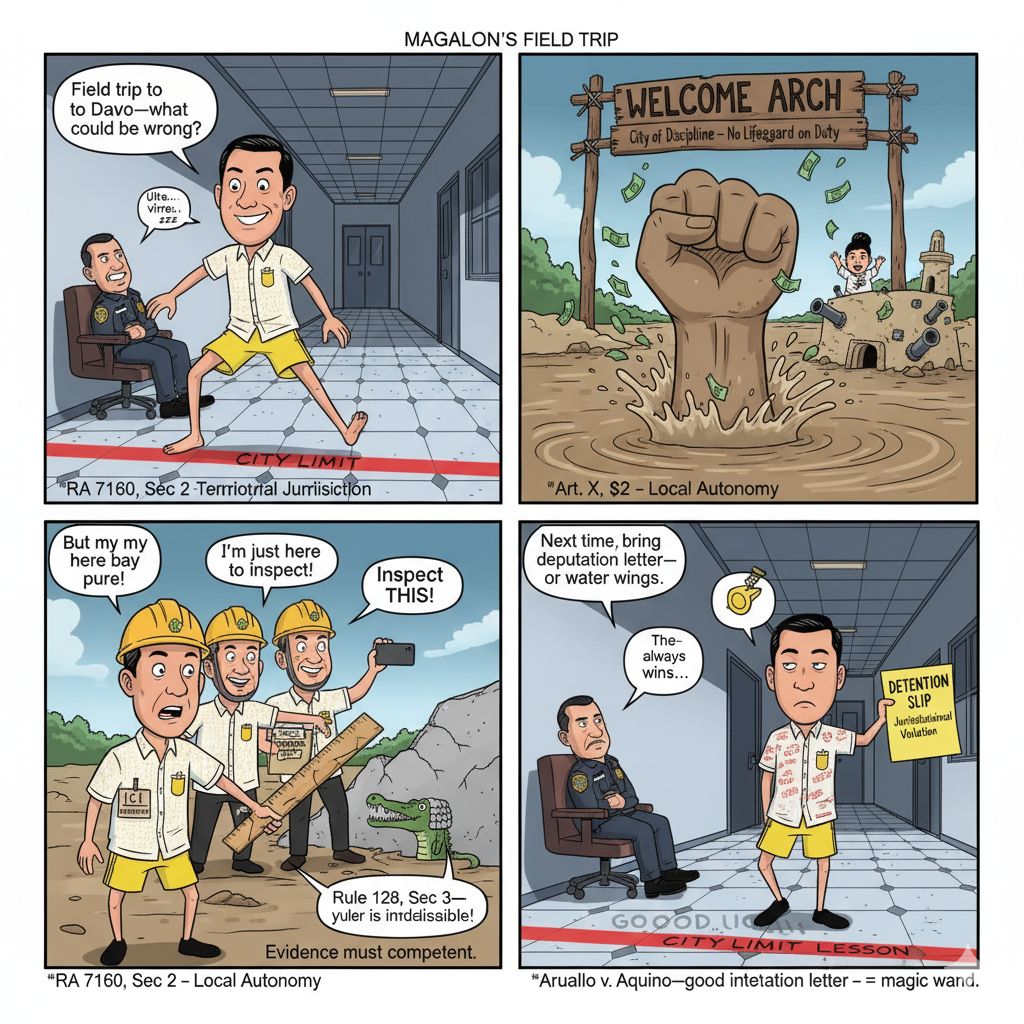

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — November 7, 2025

In a city where floods wash away public funds faster than the rain can fall, Baguio’s mayor decided to wade in — literally and legally — to inspect Davao’s “questionable” flood-control projects. The result: one man’s good intention meets the undertow of Philippine law, politics, and irony.

A Scene Worthy of a Political Documentary

There are few sights more surreal in Philippine governance than a northern mayor, in full field gear, standing ankle-deep in Davao’s muddied waters beside a former PNP chief and a DPWH undersecretary — as if reform could be achieved by inspecting the ruins of bureaucracy.

That’s precisely what happened when Baguio City Mayor Benjamin Magalong joined former PNP chief Rodolfo Azurin Jr. and DPWH Undersecretary Arthur Bisnar to inspect a flood-control project along the Davao River — one that, according to residents, collapsed faster than campaign promises.

The inspection was part of a government-wide initiative by the so-called Independent Commission for Infrastructures (ICI) to identify “questionable” projects in the Davao region (Inquirer). It’s the kind of civic theater Filipinos love: a photo op of men in long sleeves and earnest faces, examining cracked concrete while talking about “accountability.”

But this one came with a twist — the presence of Magalong, a mayor from 1,200 kilometers away, with no legal jurisdiction, no DPWH badge, and no clear reason to be there except perhaps the most dangerous one in Philippine politics: good intentions.

The Legal Question: Can a Mayor Moonlight as a National Inspector?

Under Section 444(b)(1) of the Local Government Code (RA 7160), a mayor’s authority extends only within the boundaries of his city. His job is to “exercise general supervision and control over all programs, projects, services, and activities of the city government.”

Not another city. Not a river in Davao.

So what was Magalong doing inspecting a flood-control project hundreds of kilometers south of his legal jurisdiction? Unless deputized by the DPWH, the ICI, or the Office of the President, his actions could be viewed as ultra vires — an act beyond one’s lawful authority.

True, Executive Order No. 292 (EO292), the Administrative Code of 1987, Section 38, allows inter-agency cooperation for efficiency. But “cooperation” presumes authorization, not casual attendance. There’s no known DPWH order, no ICI resolution, no presidential memo deputizing Magalong.

That makes his presence, at best, procedurally irregular, and at worst, symbolically invasive — an outsider in Davao’s tightly guarded political ecosystem.

Transparency or Trespass?

Magalong’s defenders say he was there as a reformist, a man of integrity lending moral weight to the inspection. And to be fair, the mayor has earned his reputation as a rare breed in Philippine politics — disciplined, reform-oriented, allergic to corruption.

Under RA 6713, the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials, public servants are encouraged to “uphold public interest over personal interest.” So perhaps he was simply living up to that duty, trading cold Baguio mornings for Davao’s humid symbolism.

But Section 4(e) of the same law warns against acts that could “compromise the integrity or impartiality” of one’s office. And here lies the problem: even the most upright motives become ethically ambiguous when wrapped in political optics.

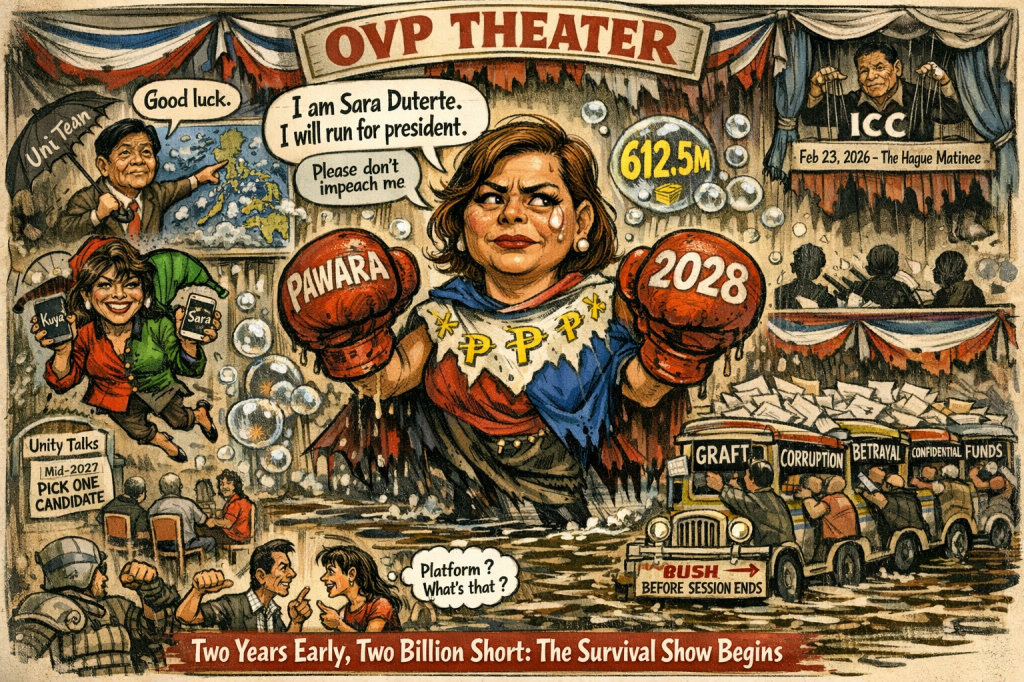

Davao is not just another city — it is the Dutertes’ citadel.

Walking into it as an outsider inspecting “questionable projects” is a legal act that instantly becomes political theater — like auditing a church while the priest is still preaching.

A Tale of Two Laws: Anti-Graft Meets Due Process

On paper, the inspection’s goal was noble — to check possible violations under RA 3019, the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, and ensure accountability for substandard public works.

But here’s the paradox: in the zeal to combat corruption, officials sometimes forget that even anti-corruption must obey procedure.

Evidence gathered without proper authorization can be rendered inadmissible under Rule 128, Section 3 of the Rules on Evidence, which requires that evidence be both “relevant and competent.”

If the inspection’s findings are used in administrative or criminal cases, a clever defense lawyer could argue that the evidence was tainted by procedural irregularity — because one of the inspectors had no legal authority to be there.

The Supreme Court has said this before — repeatedly, and with weary patience:

- People v. Doria (G.R. No. 125299, 1999): Evidence obtained through improper procedure is inadmissible.

- Pimentel Jr. v. Aguirre (G.R. No. 132988, 2000): Public officials must act strictly within their lawful authority.

- Araullo v. Aquino III (G.R. No. 209287, 2014): Good intentions cannot validate unconstitutional methods.

By that measure, Magalong’s Davao detour risks being less about transparency and more about performative reform — the kind that looks good in a press release but crumbles under legal scrutiny.

Politics in the Floodwaters

Let’s not pretend this was just about broken concrete. It was about symbolism — the northern reformist mayor entering the southern stronghold of the Dutertes, who ruled Davao for decades as their personal fiefdom.

The optics were cinematic: Magalong, the “good cop” turned mayor, walking through a city that once worshipped the “strongman” narrative. To the untrained eye, it was a governance story. To political insiders, it looked like a proxy war between reform and resentment — between the technocrat and the dynasty.

Davao’s flood-control projects are not mere engineering failures. They’re political relics, monuments to how infrastructure budgets become weapons of power. Every collapsed dike is not just a concrete failure — it’s a metaphor for the cracks in Davao’s myth of discipline and order.

The Bureaucracy Strikes Back

The DPWH loves a good inspection — it’s the government’s favorite form of public penance. They bring clipboards, cameras, and the occasional reformist mascot, hoping spectacle will substitute for accountability.

But by bringing Magalong into the mix, they invited a legal migraine. Under the COA Circular No. 2009‑006 (Rules and Regulations on Settlement of Accounts) and the DPWH Department Order No. 246, s. 2024 (Standard Templates for Variation Orders and Time-Variance–Related Requests) — alongside earlier departmental guidelines — infrastructure audits and project reviews are required to follow a defined chain of command, structured review processes, and formally authorized participation

So if this inspection leads to sanctions, expect defense lawyers to pounce:

“Your Honor, the inspection was tainted ab initio — one of the investigators had no legal authority!”

And just like that, a moral crusade might collapse under the weight of its own procedural lapses — a familiar tragedy in Philippine governance.

The Davao Dilemma: Oversight vs. Autonomy

Article X, Section 2 of the 1987 Constitution guarantees local autonomy. Each local government, even one drenched in controversy, has the right to manage its own affairs — including its own disasters.

By inspecting Davao’s projects without coordination or consent, Magalong waded into the gray waters between national oversight and local sovereignty.

The Local Government Code allows inter-LGU cooperation under Section 33, but only through formal agreements. In this case, no such agreement was publicized. So what looks like a gesture of transparency may legally resemble interference — or worse, a symbolic declaration that the “City of Discipline” now needs disciplining.

Ethics, Optics, and the Moral Irony

If the inspection was meant to show that no city is above scrutiny, it succeeded. But it also showed that no reform is above procedure.

Ethics in governance isn’t about who has the purest heart; it’s about who respects the limits that keep power accountable.

The Supreme Court called this institutional integrity in Macalintal v. COMELEC (G.R. No. 157013, 2003) — a polite way of saying even saints need written authority.

In trying to clean up Davao’s mess, Magalong may have inadvertently stepped into a political minefield: hailed as a hero in Manila, viewed with suspicion in Mindanao, and left dangling in that gray zone between moral crusader and procedural violator.

The result? A governance parable in three acts:

- The flood that destroyed the dike.

- The inspection that defied boundaries.

- The debate that washed away the point.

In the End, the River Always Wins

Davao’s floodwaters will recede, as they always do, leaving behind debris and bureaucratic fatigue. The contractors will deny wrongdoing. The DPWH will promise reforms. The ICI will issue another report. And the public — ever forgiving, ever cynical — will move on to the next scandal.

As for Magalong, his intentions were likely sincere. But as Araullo v. Aquino reminds us, “good intentions are not a magic wand.” They don’t absolve procedural sins or rewrite jurisdictional lines.

Perhaps the most telling image of that inspection wasn’t the broken dike or the samples of concrete — it was the irony of a man trying to cleanse another city’s corruption while standing on the slippery ground of administrative law.

He crossed the river, yes. But in doing so, he also crossed a line — not of morality, but of mandate.

Final Word

Magalong’s Davao expedition will be remembered as a noble gesture wrapped in legal ambiguity — a story of how even the cleanest hands can get muddy when dipped in the waters of politics.

In a country where every flood becomes a metaphor for governance, his journey reminds us of an old truth:

You can fight corruption all you want, but never without a life vest — and never without legal authority.

Key Citations:

- Lacorte, Germelina A.. “Azurin, DPWH Team Inspect Questionable Davao City Flood Control Works.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 5 Nov. 2025. Accessed 6 Nov. 2025.

- Republic of the Philippines. Republic Act No. 7160: Local Government Code of 1991. 10 Oct. 1991. Official Gazette. Accessed 6 Nov. 2025.

- Philippines. Supreme Court of the Philippines. Executive Order No. 292 – The “Administrative Code of 1987“. 3 Aug. 1987. Supreme Court E-Library. Accessed 6 Nov. 2025.

- Republic of the Philippines. Republic Act No. 6713: Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees. 20 Feb. 1989. LawPhil Project. Accessed 6 Nov. 2025.

- Republic of the Philippines. Republic Act No. 3019: Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. 17 Aug. 1960. Official Gazette. Accessed 6 Nov. 2025.

- Philippines. Revised Rules on Evidence (Rules 128-134, Rules of Court). Amended per Resolution adopted on March 14, 1989. LawPhil Project. Accessed 6 Nov. 2025.

- People of the Philippines v. Florencio Doria y Bolado and Violeta Gaddao y Catama, G.R. No. 125299, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 22 Jan. 1999. Accessed 6 Nov. 2025.

- Pimentel Jr., Aquilino Q., petitioner, vs. Hon. Alexander Aguirre, in his capacity as Executive Secretary, Hon. Emilia Boncodin, in her capacity as Secretary of the Department of Budget and Management, respondents, Roberto Pagdanganan, intervenor. Supreme Court of the Philippines, 391 Phil. 84 (1999). Supreme Court E-Library. Accessed 6 Nov. 2025.

- Araullo, Maria Carolina P., petitioner, et al. v. Benigno Simeon C. Aquino III, President of the Republic of the Philippines, et al. G.R. No. 209287. Supreme Court of the Philippines, 1 July 2014. Accessed 6 Nov. 2025.

- Commission on Audit. COA Circular No. 2009-006: Prescribing the Use of the Rules and Regulations on Settlement of Accounts. 15 Sept. 2009. Supreme Court E-Library. Accessed 6 Nov. 2025

- Department of Public Works and Highways. Department Order No. 36, s. 2010, “Reinstatement of Accreditation of DPWH Materials Engineers Who Passed the Contractors’ and Consultants’ Materials Engineers Accreditation Examination.” 2010, Philippine Judiciary eLibrary.

- Philippines. Department of Public Works and Highways. Department Order No. 246, Series of 2024: Standard Templates for Variation Order and Time Variance–Related Requests. Manila: DPWH, 2024.

- Republic of the Philippines. “The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines.” Official Gazette. Accessed 6 Nov. 2025.

- Philippines. Supreme Court of the Philippines. Macalintal v. COMELEC, G.R. No. 157013, July 10, 2003. Supreme Court E-Library. Accessed 6 Nov. 2025.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment