₱58 Million Per Head: When Silence Pays Better Than Speaking Up

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — December 30, 2025

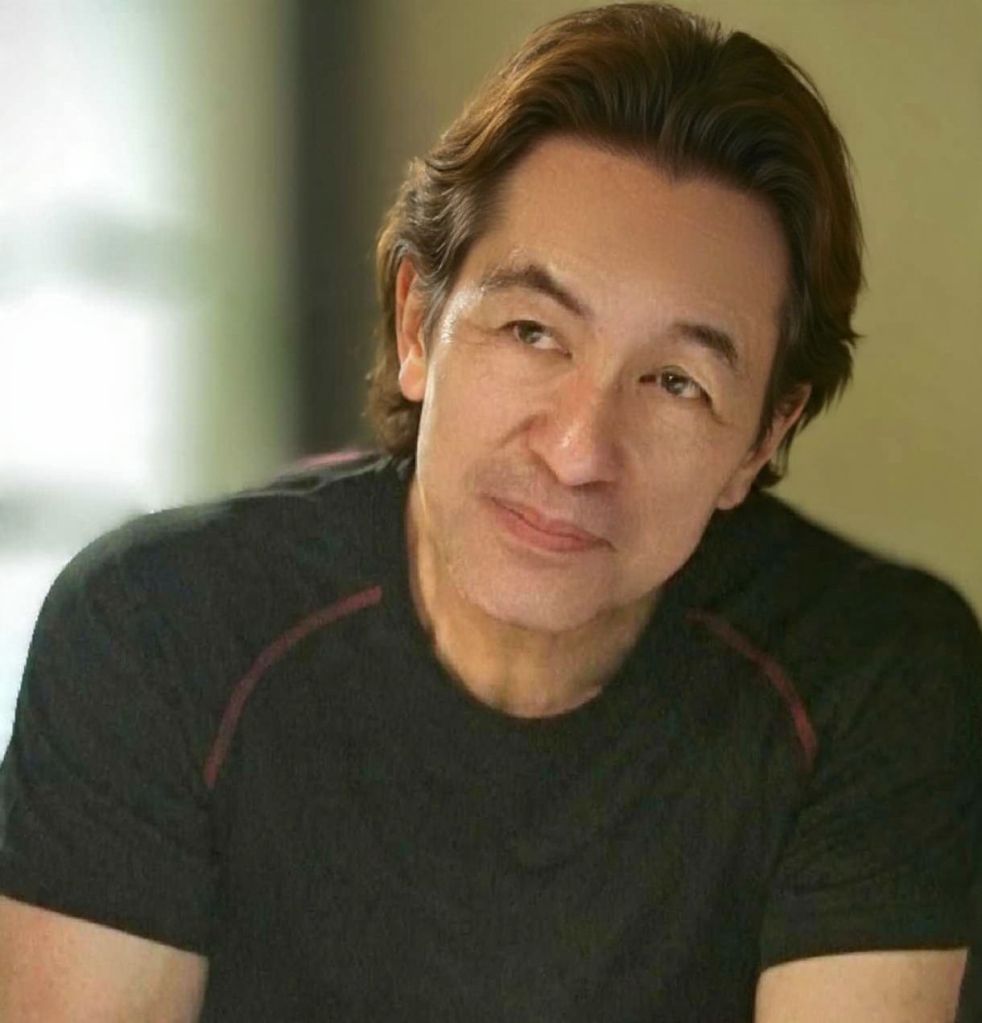

Behold, the Lower House of the Philippine Congress—that august body where the “power of the purse” is wielded like a magician’s wand, making billions disappear into thin air while everyone claps politely. But on December 27, 2025, even as the nation nursed its holiday hangover, Batangas Rep. Leandro Leviste decided to yank back the curtain on this fiscal farce. Leviste, a vice chairman of the Committee on Appropriations (yes, you read that right—he’s supposedly in the room where it happens, yet claims he’s “out of the loop”), demanded a simple breakdown of the House’s proposed ₱27.7 billion internal budget for 2026 (Manila Bulletin, 27 Dec. 2025). That’s a cool ₱10.5 billion jump from the current ₱17.2 billion, with no explanation, no hearings, and apparently no shame.

This isn’t just a budget squabble, folks. This is a full-blown spectacle of institutional hypocrisy, where the guardians of public funds treat their own piggy bank like a secret slush fund, all while lecturing the executive on fiscal restraint. It’s a direct assault on the sacred principles of the 1987 Philippine Constitution, and if ratified without scrutiny, it will cement Congress as the untouchable aristocracy of Philippine graft.

The Legal Knife: Slicing Through the Opaque Veil

Let’s sharpen the blade and dissect this mess with the cold precision of Philippine law.

First, the ₱10.5 billion unexplained increase. The House ballooned its Maintenance and Other Operating Expenses (MOOE) from ₱10.75 billion to ₱18.58 billion—translating to a jaw-dropping ₱58.42 million per lawmaker in a 318-member body. Leviste points out that lawmakers get monthly MOOE allotments plus “bonuses” in October and December, conveniently timed with budget approvals. And much of this MOOE? Liquidated “by certification”—meaning no receipts required, just a solemn swear that the money went to “legislative functions.” Cute.

This practice reeks of the ghosts the Supreme Court exorcised in Belgica v. Ochoa (G.R. No. 208566, November 19, 2013), where the pork barrel system (Priority Development Assistance Fund or PDAF) was declared unconstitutional for allowing post-enactment legislator interference in fund execution—violating separation of powers and public accountability. Here, unevenly distributed “incentives” and certification-only liquidation echo the same banned informal practices: lump-sum discretion that lets individual solons play god with public money.

Worse, the House’s self-appropriation flouts the spirit—if not the letter—of Article VI, Section 25(1) of the 1987 Constitution: “The Congress may not increase the appropriations recommended by the President for the operation of the Government as specified in the budget.” While technically aimed at executive branches, the “power of the purse” demands fiscal restraint and transparency across government. Jacking up your own budget by 61% without justification? That’s not restraint; that’s gluttony.

Then there’s the alleged “incentive” offer. Leviste revealed that a staffer from Appropriations Chair Mika Suansing’s office secretly showed him a list totaling ₱151 million in project allocations, whispering, “Cong, this is your incentive”—a week before the national budget vote. (Suansing denies it influences votes, of course.) This screams Section 3(e) of Republic Act (R.A.) No. 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act): causing undue injury to the government or giving unwarranted benefits through manifest partiality, evident bad faith, or gross inexcusable negligence.

And that “liquidation by certification”? It’s a neon-lit gateway to malversation under Article 217 of the Revised Penal Code—public funds vanishing without audit-proof trails. It blatantly mocks R.A. No. 6713 (Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees), which demands transparency and accountability. The Supreme Court in Araullo v. Aquino (G.R. No. 209287, July 1, 2014) struck down the Disbursement Acceleration Program (DAP)’s cross-border realignments for similar reasons: funds must stick to their appropriated purpose, no funny business.

Chair Suansing and the House leadership hide behind “collegial body” excuses and internal rules, ignoring Leviste’s unanswered requests for breakdowns. Even a vice chairman gets ghosted? That’s not collegiality; that’s a cult of secrecy.

Prosecution and Consequences: Time to Pay the Piper

If this ₱27.7 billion opacity sails through ratification, the fallout will be catastrophic.

Politically, it widens rifts in the majority bloc—Leviste, the young billionaire neophyte refusing his own salary and MOOE, versus the old guard gatekeepers. Institutionally, it erodes the “power of the purse” into a punchline, inviting Supreme Court challenges like Belgica and Araullo redux.

Public trust? Already in the gutter. Ratify this black box, and Filipinos will rightly see Congress as a self-serving cartel, fueling cynicism and disengagement.

Accountability pathways are clear: The Office of the Ombudsman (under R.A. No. 6770, The Ombudsman Act of 1989) should launch a motu proprio probe into the “incentive” offers (potential bribery/graft) and uneven distributions. The Commission on Audit (COA) must conduct a special audit of House MOOE, zeroing in on “liquidation by certification” to check for circumvention of accounting rules.

The Call to Arms: No More Hiding

Mga kababayan, enough. Leviste’s lone voice—refusing his perks while his colleagues feast—shines a rare light, but one man can’t drain this swamp.

Demand prosecution where evidence of graft emerges. Insist on immediate, full public transparency: a line-item breakdown of the entire ₱27.7 billion, including every MOOE peso and “incentive.”

And real reform: Ban liquidation by certification for legislative funds—require receipts like every other public servant. Legislate mandatory detailed disclosures for Congress’s own budget, ending this aristocratic exemption.

The House leadership and Appropriations Committee owe us answers, not silence. Break it down, or we break you down—at the ballot box, in the courts, and in the court of public opinion.

Transparency now. Accountability forever.

— Louis “Barok” C. Biraogo

Kweba ni Barok

Key Citations

- Philippine Constitution. (1987). The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines, Article VI. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines.

- Republic Act No. 3019. (1960, August 17). Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines.

- Republic Act No. 6713. (1989, February 20). Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines.

- Republic Act No. 6770. (1989, November 17). The Ombudsman Act of 1989. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines.

- Belgica v. Executive Secretary Ochoa. G.R. No. 208566. Supreme Court of the Philippines, 19 Nov. 2013. LawPhil.

- Araullo v. Aquino. G.R. No. 209287. Supreme Court of the Philippines, 1 July 2014. LawPhil.

- Quismorio, Ellson. “Break It Down: Leviste Wants to Know How House Will Spend ₱27.7-B Internal Budget.” Manila Bulletin, 27 Dec. 2025.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

Leave a comment