Meanwhile, the ₱50 Billion AFP Modernization Fund Gets a Loving Presidential Hug

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — January 8, 2026

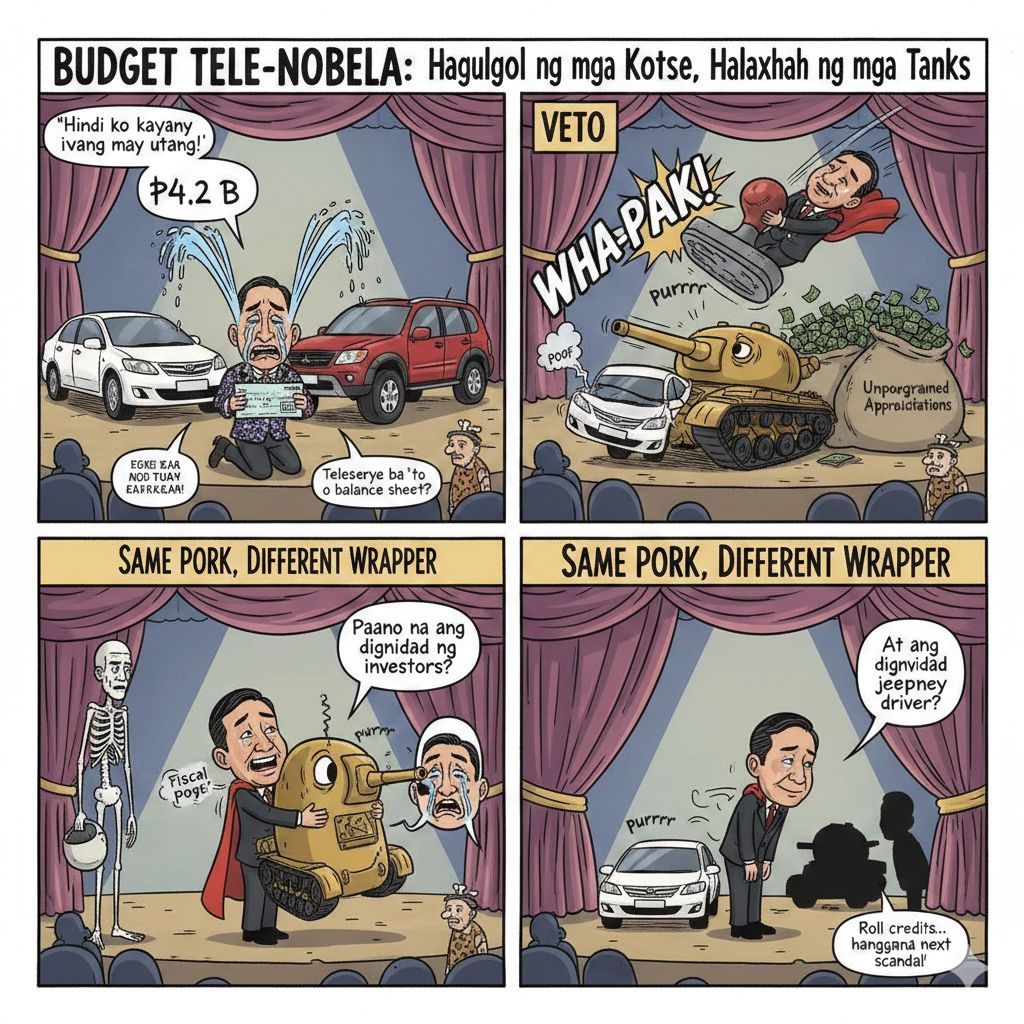

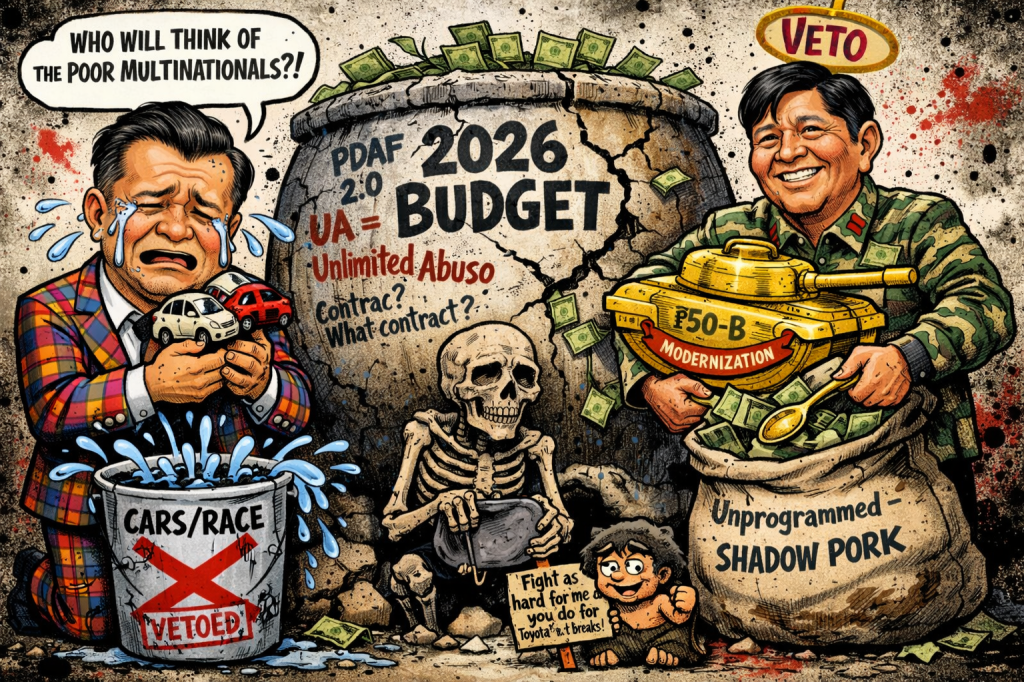

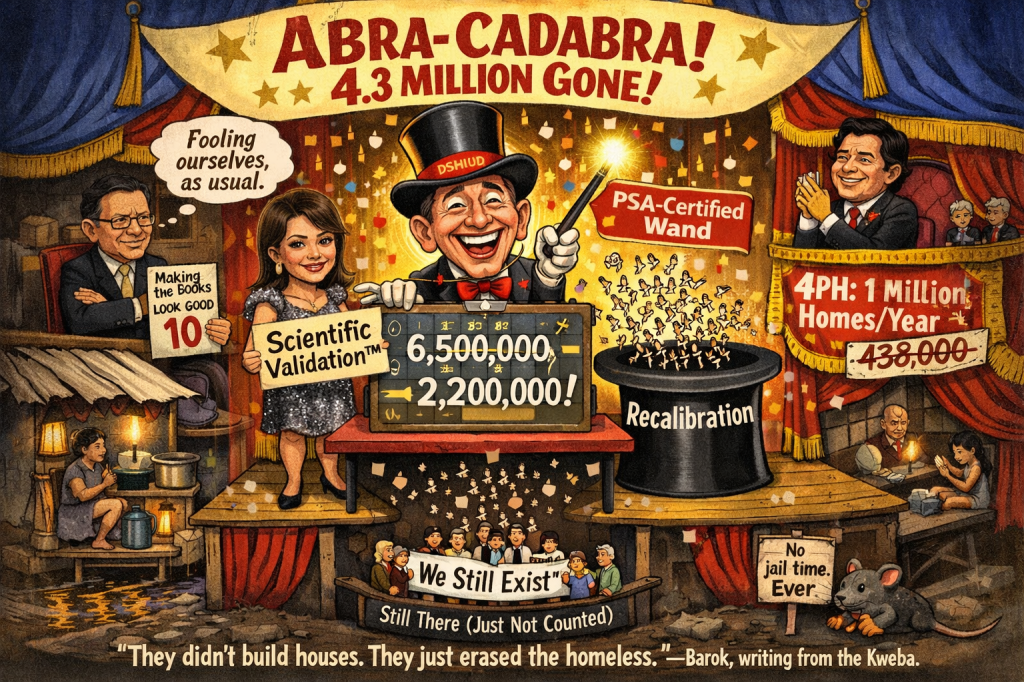

MGA ka-kweba, on January 5, 2026, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. signed the 2026 General Appropriations Act (GAA), a ₱6.793-trillion budget brimming with drama, vetoes, and the ever-persistent unprogrammed appropriations (UA) – standby funds released only upon excess revenue or loan proceeds. Here we are again: a senator pretending to defend obligations, a president pretending to clean up the budget, and a mechanism long reeking of rot – the UA, the shadow pork barrel that refuses to die despite repeated Supreme Court slaps.

Let’s not fool ourselves. This controversy – Marcos’ veto of ₱92.5 billion in UA, including ₱4.2 billion for the Comprehensive Automotive Resurgence Strategy (CARS) Program and Roadmap for Automotive Component Excellence (RACE) Program (to settle debts with Toyota and Mitsubishi) and ₱35 billion for Government Counterpart for Certain Foreign-Assisted Projects – is not mere “fiscal discipline.” It is a classic clash between contractual honor and political discretion, played out in a budgetary loophole historically exploited for corruption.

The Two Faces of Hypocrisy: Gatchalian vs. Marcos

First, Senator Sherwin Gatchalian, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, suddenly championing foreign investors. He says it’s “embarrassing” for Toyota and Mitsubishi because for five years we’ve failed to pay the tax incentives promised under the CARS program. He’s right there – these are existing obligations, not new spending. It’s just a “book entry,” he claims, shifting debt from the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) to the government. And the ₱35 billion counterpart? Without it, foreign loans won’t be released, stalling projects.

But hold on, Sen. Gatchalian: why park these in unprogrammed funds in the first place? You know they’re most vulnerable to veto and ripe for abuse. Your “workarounds” – tapping the Office of the President (OP) contingency funds or coordinating between the Department of Budget and Management (DBM) and BIR – further erode budgetary transparency. It’s as if you’re saying, “It’s fine to bypass Congress, as long as we pay.” Is this genuine stewardship, or political theater to appear “pro-business” while preserving discretionary slush funds? Truth is, you’re both playing in the same rotten system.

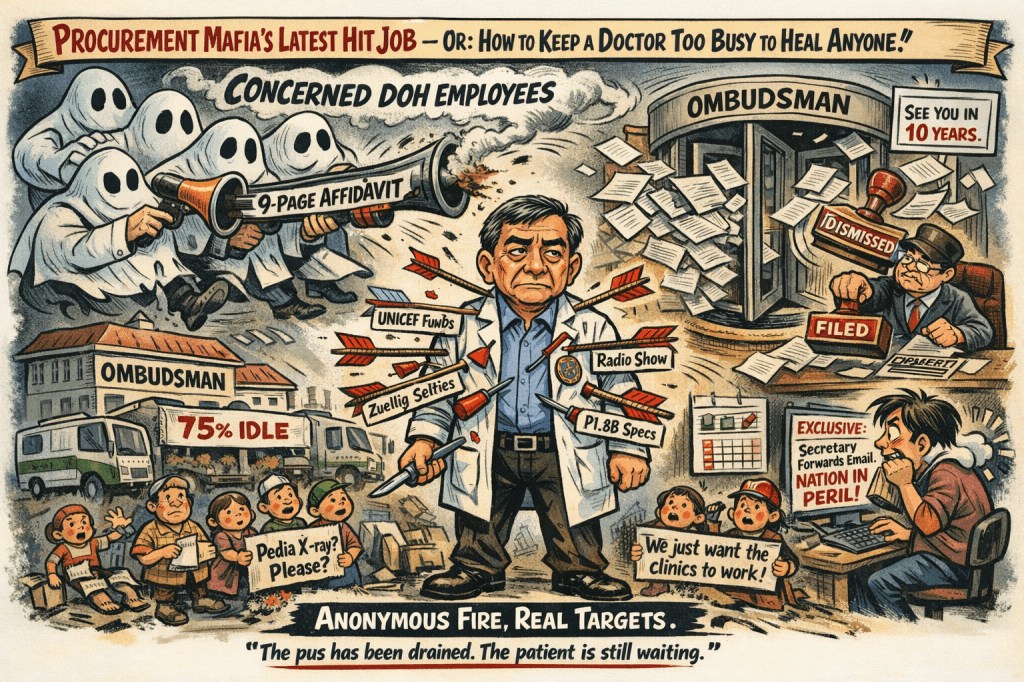

And President Marcos? He patted himself on the back for vetoing ₱92.5 billion, touting a “clean budget” and fiscal discipline. But why selective? Why spare ₱50 billion for the Revised Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) Modernization Program, ₱97.3 billion for Support to Foreign-Assisted Projects, and ₱3.6 billion for Risk Management? Why are big, graft-prone items (military upgrades, foreign projects) untouchable, while contractual obligations to Toyota/Mitsubishi and essential counterparts for loan releases get axed?

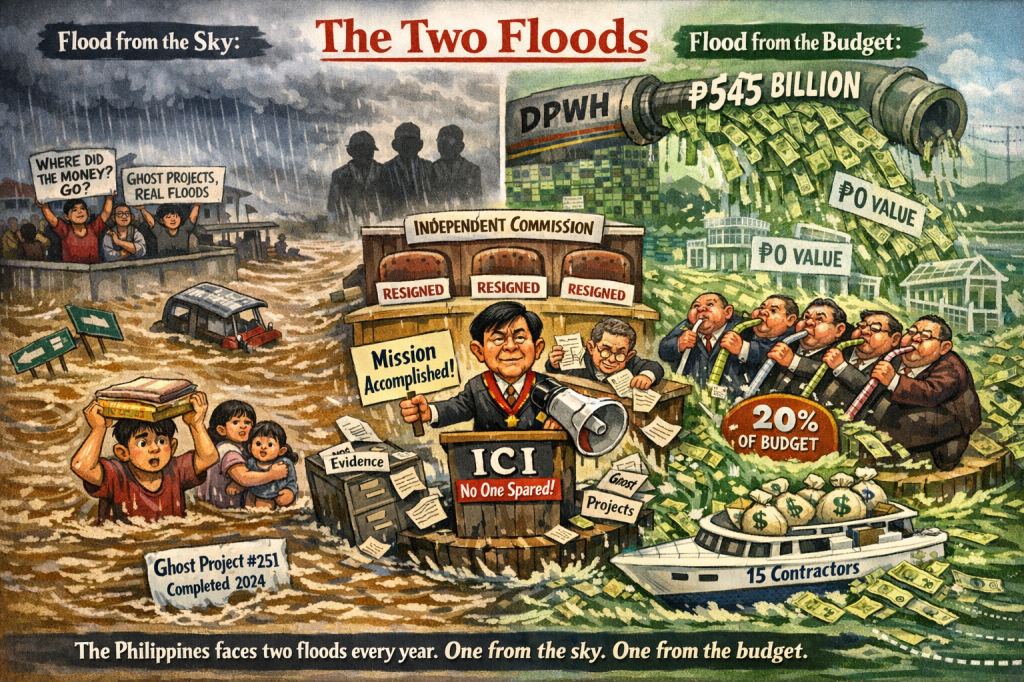

Is this principled discipline, or political sleight-of-hand? Amid scandals over billions in kickbacks from flood control projects, Marcos suddenly poses as an anti-corruption hero – yet leaves ₱150.9 billion in UA, the lowest since 2019, but still ample for discretionary releases. It’s selective vetoing for brownie points while retaining control over large pots.

The Real Monster: Unprogrammed Appropriations as Shadow Pork

Let’s not deceive ourselves – the core scandal is the UA mechanism itself. Standby funds released only with excess revenue or loans, but historically a “backdoor pork” for patronage and corruption. Remember the Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF) scandal? This is its descendant.

UA is legally ambiguous: allowed in the GAA with clear conditions, but triggers often vague, enabling executive overreach. It violates Article VI, Section 29 of the 1987 Constitution (power of the purse vested in Congress) and Section 25 (no money paid except pursuant to an appropriation). It bypasses line-item budgeting, becoming a slush fund for political favors.

Ground it in law: In Belgica v. Ochoa (G.R. No. 208566, 2013), the Supreme Court struck down PDAF for unconstitutional post-enactment project identification – delegating legislative power to the executive or lawmakers. Though UA wasn’t directly voided then, the spirit is clear: no unregulated discretion mechanisms.

In Philconsa v. Enriquez (G.R. No. 113105, 1994), item vetoes were upheld but must be reasonable, not arbitrary. Marcos’ selective veto? Arguably abuse of discretion, especially axing contractual obligations while preserving large discretionary items.

On the contractual side: Failing to pay Toyota and Mitsubishi risks breach under Republic Act No. 7042 (Foreign Investments Act of 1991). They could sue or trigger investor arbitration – embarrassing internationally and further eroding foreign direct investment (FDI) confidence. Same for foreign-assisted projects: no counterpart, no loan release, stalling infrastructure and development.

Ethically: This flouts Republic Act No. 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act) if enabling misuse, and Republic Act No. 6713 (Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees) prioritizing public interest.

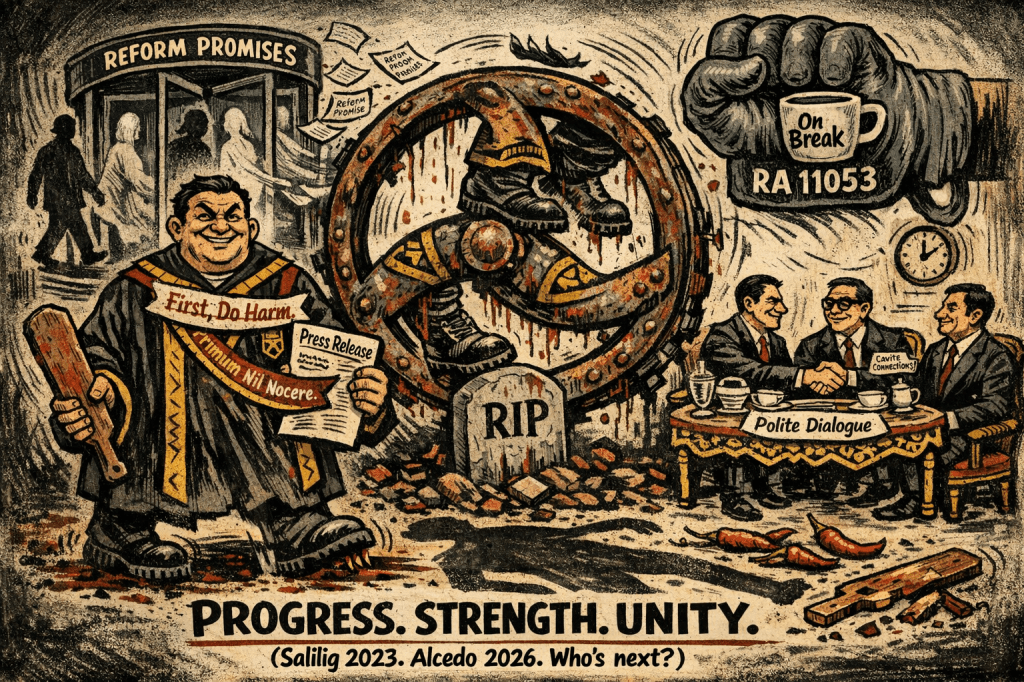

Broader Implications: Public Trust in Government, Fading Fast

The fallout? It will shatter investor confidence – how can foreigners invest if we renege on promises? Foreign-assisted projects stall, costing jobs and growth. And public trust? Amid flood control scandals and family dramas (Sen. Imee calling the budget “sneaky”), faith in governance plummets further.

My recommendations, no beating around the bush:

- Judicial intervention: Challenge UA constitutionality in the Supreme Court. Time to bury it for good, like PDAF.

- Honor contractual obligations – as a matter of national integrity. Pay Toyota, Mitsubishi, and counterparts, even via supplemental budget.

- Overhaul the system: Scrap discretionary slush funds. Shift to genuine program-based, transparent budgeting. Zero UA, automatic appropriations for obligations, strict oversight.

Mga ka-kweba, as long as UA lives, institutionalized corruption thrives. Gatchalian and Marcos? They’re both cavorting in the same cave. Time to clean it out thoroughly – for the people, not pockets.

- – Barok, still waiting for the day our leaders fight as hard for the jeepney driver as they do for Toyota’s tax breaks

Key Citations

- Abarca, Charie. “Gatchalian Questions Vetoed Items in 2026 Unprogrammed Funds.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 6 Jan. 2026.

- The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines.

- Republic Act No. 3019, Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, 17 Aug. 1960, LawPhil Project.

- Republic Act No. 6713, Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees, 20 Feb. 1989.

- Republic Act No. 7042, Foreign Investments Act of 1991, 13 June 1991, LawPhil Project.

- Belgica v. Executive Secretary Paquito N. Ochoa, Jr., G.R. No. 208566, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 19 Nov. 2013, LawPhil Project.

- Philippine Constitution Association v. Enriquez. G.R. No. 113105, 19 Aug. 1994, Supreme Court of the Philippines, LawPhil Project.

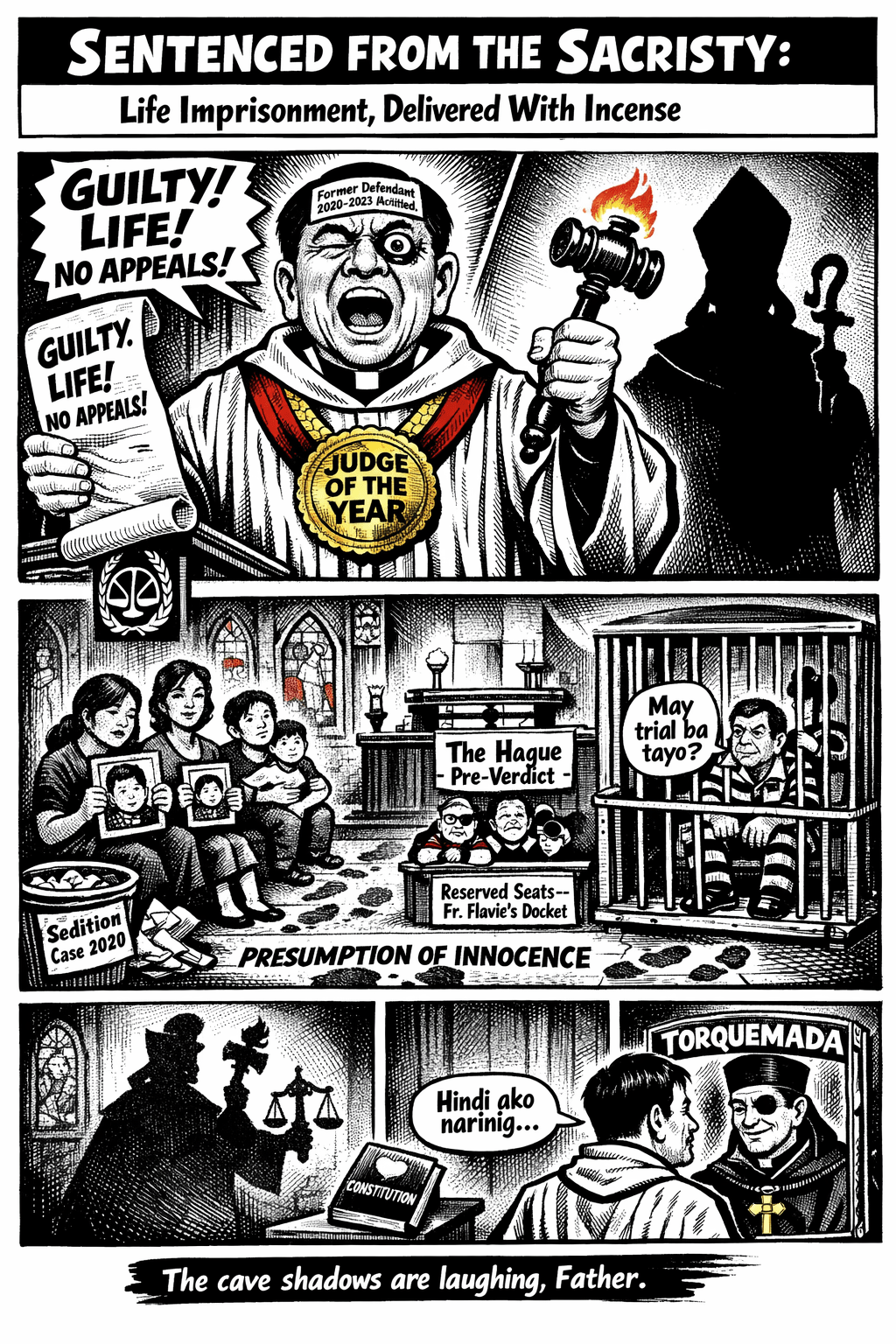

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

Leave a comment