Fake Nudes, Baseless Drugs, and Economy Excuses: Dissecting Malacañang’s Melodramatic Diversion

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — January 9, 2026

Satirical Headline Hook:

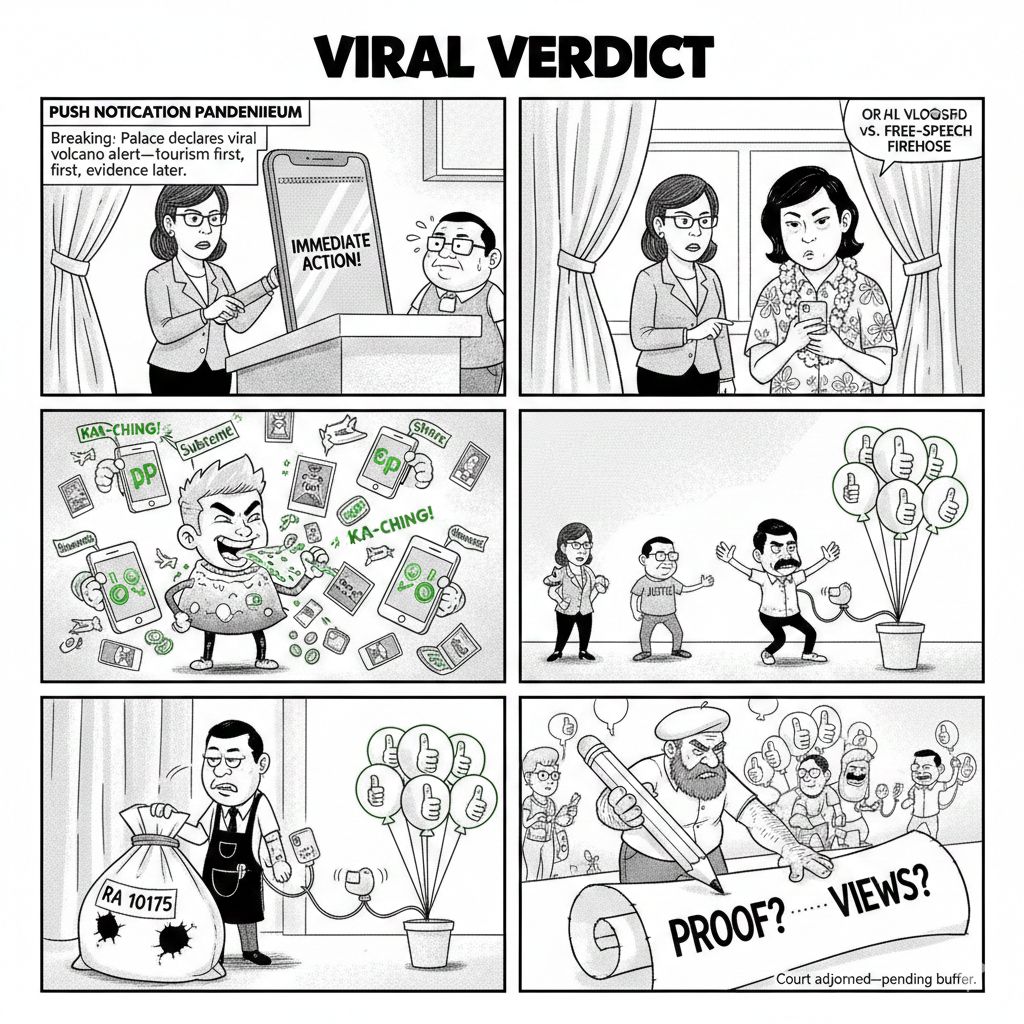

Palace Demands “Immediate Action” Against Vlogger’s Bombshell: But Is This Cyberlibel, Privacy Invasion, or Just Another Chapter in the Endless Marcos Family Feud Gone Viral?

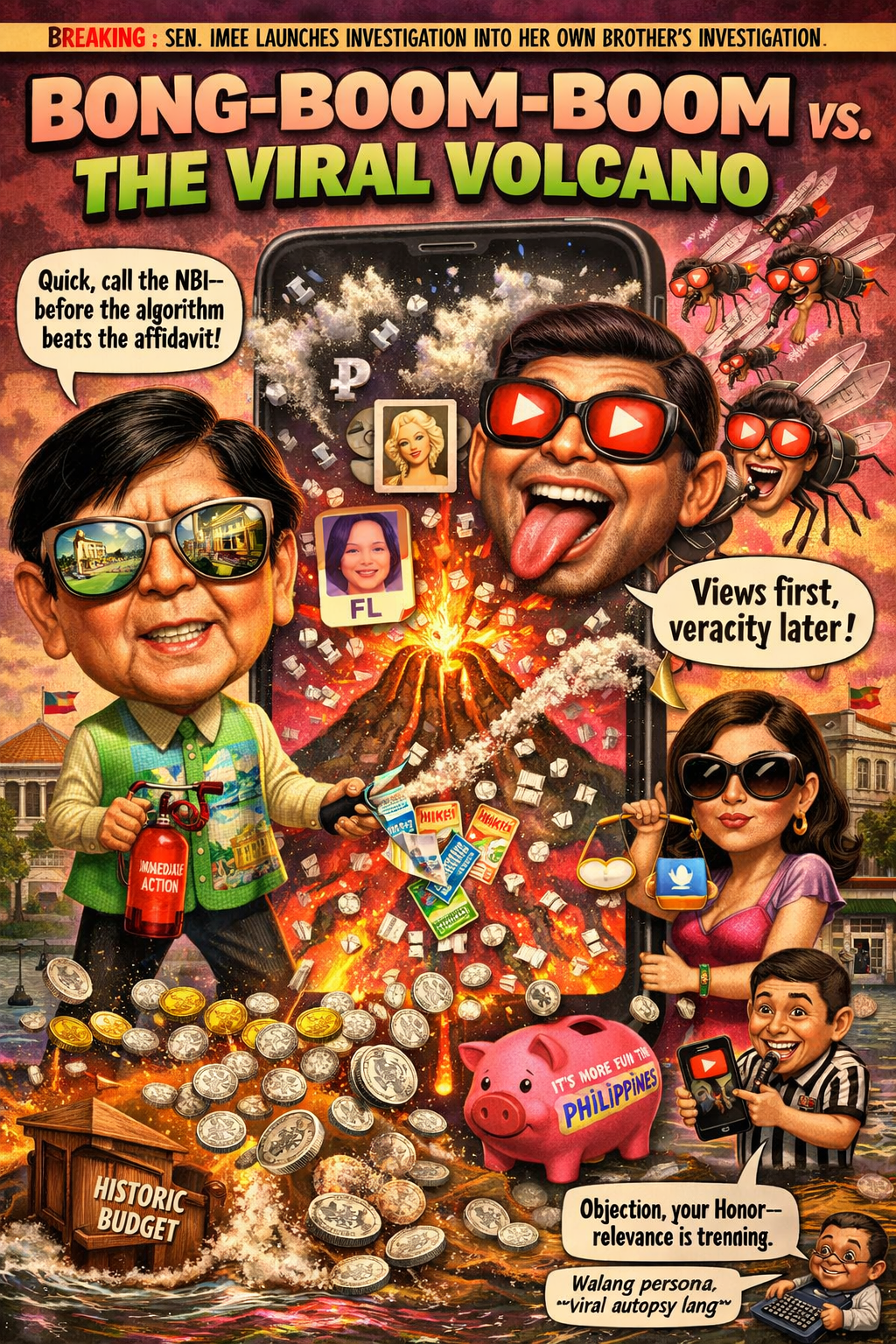

MGA ka-kweba, welcome to the newest season of Philippine political telenovela—where baseless accusations spread faster than misinformation on social media, and Malacañang responds with the poised indignation of a scripted drama. Our cast of characters: The dignified First Couple, President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. and First Lady Liza Araneta-Marcos, cast as the wronged protagonists; Palace Press Officer Claire Castro as the steadfast guardian calling for “immediate action”; and the provocateur vlogger Deen Chase, hurling claims of illegal drug use and circulating a supposed explicit photo of the First Lady like it’s prime-time evidence.

The Forensic Dissection: Unpacking This Scandal Layer by Layer

The allegations: Vlogger Deen Chase accuses the First Couple of illegal drug use and shares an alleged sensitive, explicit photo of the First Lady. No hard evidence—just viral assertions. Palace Press Officer Claire Castro counters via media messages, labeling it “rumors” designed to “harm their character and integrity,” classic “fake news” peddled for political gain or paid provocation. She stresses the need for “immediate action,” warning of damage to tourism and the economy (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 8 Jan. 2026).

This follows the familiar script: “Fake news” versus “malicious falsehoods.” But what exactly is this “immediate action”? Filing a complaint under the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012 (Republic Act No. 10175)? Or a media counteroffensive?

The Legal Arena

Defamation and Cyberlibel: Article 353 of the Revised Penal Code (RPC) defines libel as a public, malicious imputation of a crime or vice causing dishonor. Section 4(c)(4) of Republic Act No. 10175 extends this to online platforms with enhanced penalties.

Key elements: publication (viral—check), identifiability (the First Couple—clear), falsity (presumed absent proof), and malice (actual or reckless disregard).

Philippine courts do not fully adopt the U.S. “actual malice” rule for public figures. However, reckless failure to verify can infer malice, as upheld in Disini Jr. v. Secretary of Justice (G.R. No. 203335, February 11, 2014), which affirmed cyberlibel’s constitutionality for original authors.

If Chase spread unverified falsehoods, prosecution is viable—prior cases demonstrate enforcement. Truth remains a complete defense, but evidence is absent here.

The proof dilemma: Virality thrives on speculation in public discourse; courts demand rigorous evidence.

Privacy and Personality Rights: Unauthorized circulation of intimate images—even if authentic—violates Civil Code provisions on privacy (Articles 26 and 723, allowing damages for mental anguish). If fabricated or AI-generated, it strengthens defamation claims under RA 10175.

Free Speech Protections: Article III, Section 4 of the 1987 Constitution guarantees no abridgment of expression. Both sides invoke it—Chase as “exposure,” the Palace as reputation defense—highlighting selective application in our polarized landscape.

Motivation Analysis: Decoding the Players

- Deen Chase: Likely driven by the vlogger ecosystem—views, subscribers, monetization. Possible political motives or genuine (unsubstantiated) conviction.

- Claire Castro/Malacañang: Safeguarding the administration’s image and deterring further assaults amid ongoing tensions.

- The First Couple: Options include legal action, strategic silence, or transparent rebuttal (e.g., accredited drug testing).

- Netizens/Public: Amplifiers fueled by bias, perpetuating the cycle.

Broader Context: A Recurring Marcos Narrative

This echoes late 2025, when Senator Imee Marcos publicly accused her brother of long-term drug use in a rally speech, claims swiftly denied by the Palace as baseless. It fits a pattern of intra-family and political conflict amplified by social media’s disinformation machinery—fabricated documents, manipulated images as weapons in a noisy public sphere.

Potential Outcomes and Implications

Scenarios:

- Chase faces charges if claims prove false; retracts if pressured.

- Palace gains short-term narrative control but risks credibility if no follow-through.

- Lingering rumors shadow the First Couple, fueling polarization.

Broader fallout: Diminished institutional trust, speech chill, or stronger online accountability precedents. Internationally, it risks reinforcing stereotypes, impacting diplomacy and investment.

The Barok Verdict: Demanding Accountability and Sanity

Pursue evidence-driven justice: Let the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) or Department of Justice (DOJ) probe impartially. Prosecute cyberlibel if warranted under RPC Articles 353–355 and RA 10175 Section 4(c)(4); address privacy breaches civilly. Absent merit, halt the spectacle.

Public officials merit scrutiny, but vloggers bear responsibility for falsehoods. Advocate verified facts, ethical discourse, and digital literacy to rise above intrigue.

Court adjourned, gossip dismissed, sanity barely survived—walang personalan, legal autopsy lang.

–Barok

Key Citations

- Cabato, Luisa. “Palace Wants Immediate Action vs Latest Allegations on First Couple.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 8 Jan. 2026.

- Philippines. The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines.

- Disini Jr. v. Secretary of Justice, G.R. No. 203335, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 11 Feb. 2014, LawPhil Project.

- Republic Act No. 10175: An Act Defining Cybercrime, Providing for the Prevention, Investigation, Suppression and the Imposition of Penalties Therefor and for Other Purposes [Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012]. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, 12 Sept. 2012.

- Philippines. Act No. 3815: An Act Revising the Penal Code and Other Penal Laws. 8 Dec. 1930. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines.

- Philippines. Republic Act No. 386: An Act to Ordain and Institute the Civil Code of the Philippines. 18 June 1949. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines.

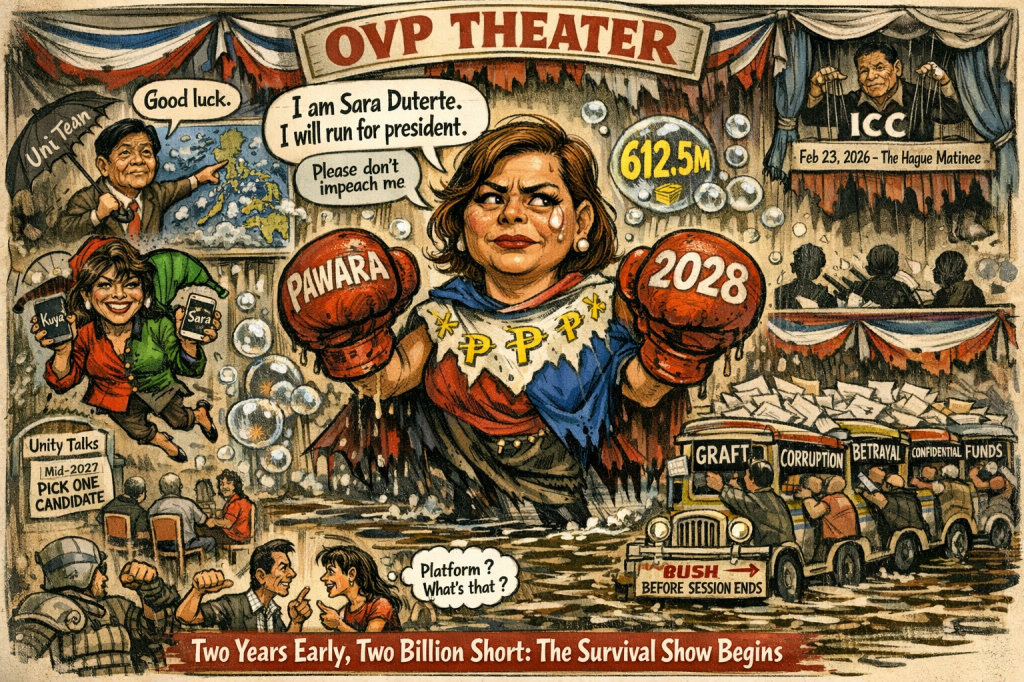

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

- $2 Trillion by 2050? Manila’s Economic Fantasy Flimsier Than a Taho Cup

Leave a comment