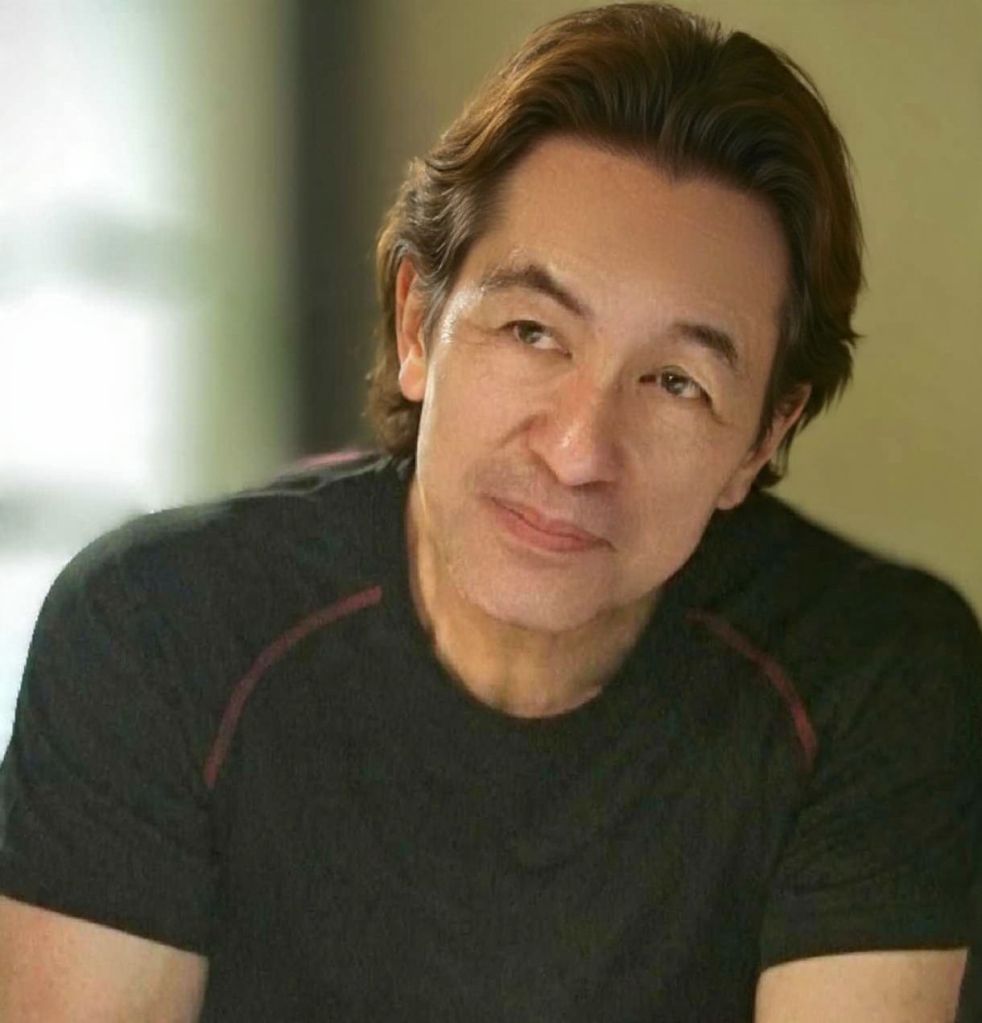

From Congressional Pork to Mayoral Barbecue – Same Meat, New Grill

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — January 16, 2026

IF money really is the root of all evil, then ₱1.19 trillion is an entire forest.

That is the National Tax Allotment (NTA) amount the Marcos Jr. administration plans to entrust to local government units (LGUs) in the 2026 national budget—defended as decentralization, efficiency, and anti-corruption reform. National agencies, we are told, are too slow, too bloated, too corrupt. LGUs, by contrast, are closer to the people and therefore cleaner (BusinessWorld, 28 Dec. 2025).

The 1987 Constitution allows this move.

The law, however, warns us what happens next.

I. Constitutionally Permissible, Legally Dangerous

Let us begin with the easy question.

Is the ₱1.19 trillion LGU allocation constitutional?

Yes—almost certainly.

Article X of the 1987 Constitution mandates local autonomy and fiscal empowerment of LGUs. This constitutional command was operationalized—and dramatically expanded—by the Supreme Court in Mandanas v. Ochoa (G.R. Nos. 199802 & 208488, July 3, 2018; resolution April 10, 2019), which required that LGUs receive a share from all national taxes, not merely internal revenue collections.

Congress, exercising the power of the purse under Article VI, Section 29, enjoys wide latitude in determining budgetary allocations. The Supreme Court has consistently held that courts will not interfere with policy choices embedded in appropriations laws absent a clear constitutional violation.

Any facial constitutional challenge to the ₱1.19 trillion allocation is therefore unlikely to prosper.

But constitutionality is not the end of the inquiry. It is the beginning.

II. Decentralization Is Not a Legal Antidote to Corruption

Interior Secretary Jonvic Remulla’s now-famous comparison—₱21.5 million for an LGU-built school versus ₱36 million for a nationally implemented one—has become the administration’s rhetorical shield.

The law is unimpressed by anecdotes.

Philippine anti-corruption statutes are actor-neutral.

The Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act (Republic Act No. 3019) penalizes public officers regardless of whether they sit in Manila or a municipal hall.

The Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees (Republic Act No. 6713) imposes the same duties of accountability, transparency, and professionalism on mayors as it does on cabinet secretaries.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasized that local autonomy does not diminish accountability. In Pimentel v. Aguirre (G.R. No. 132988, July 19, 2000), the Court held that autonomy exists within the framework of national law, not above it.

Decentralization changes who spends public money.

It does not change how temptation works.

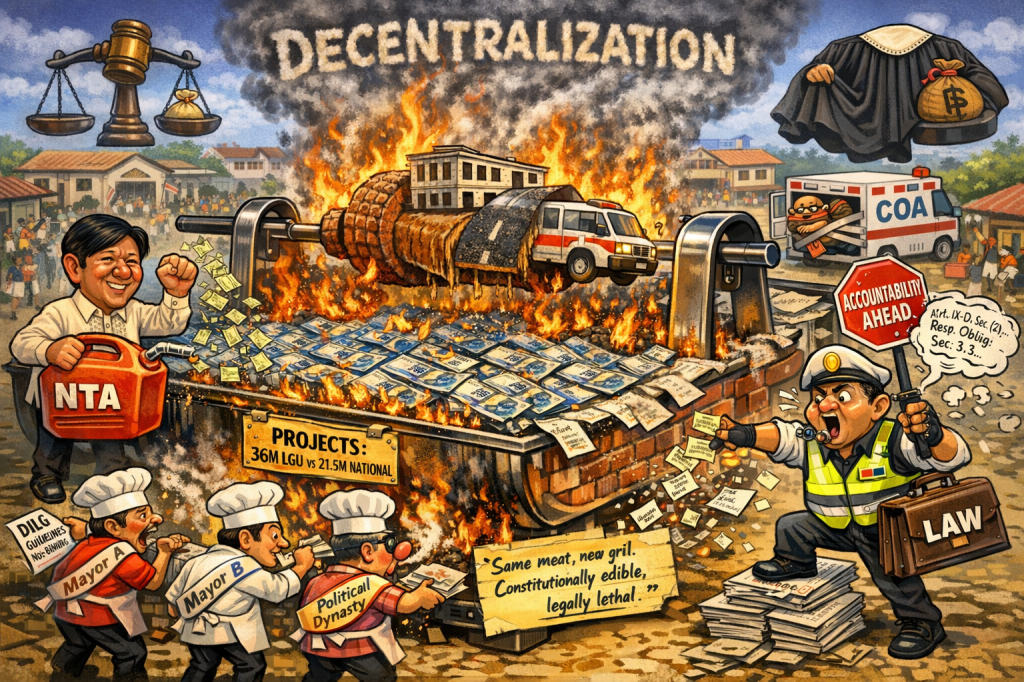

III. The Pork Barrel Doctrine and Its Modern Disguises

This is where the legal alarm bells should ring.

In Belgica v. Ochoa (G.R. No. 208566, Nov. 19, 2013), the Supreme Court struck down the Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF) not simply because legislators touched public money, but because it vested post-enactment discretion in the absence of meaningful accountability.

The Court made clear that:

“What is constitutionally impermissible is the authority to determine how public funds shall be spent after the budget law has been passed.”

When LGU support funds are:

- large in scale,

- weakly earmarked,

- politically timed, and

- governed primarily by administrative circulars rather than statute,

they begin to resemble the very structures condemned in Belgica—even if the hands on the money are local rather than legislative.

The Constitution forbids discretion divorced from accountability, not merely congressional pork.

IV. The Budget as a Legal Fiction of “Trust”

Budget Secretary Rolando Toledo has described the 2026 budget as a “contract of trust” between the national government and LGUs.

But public finance law does not recognize trust without enforcement.

In Araullo v. Aquino (the DAP case, G.R. No. 209287, July 1, 2014), the Supreme Court warned that even well-intentioned budgetary innovations cannot bypass constitutional and statutory controls. Good faith does not legalize structural defects.

A lawful expenditure regime requires:

- A clearly defined public purpose

- Measurable and verifiable outcomes

- Independent audit and oversight

- Consequences for misuse or failure

Absent these, a budget becomes what the Court has repeatedly cautioned against: a political document masquerading as a legal instrument.

V. COA, Delay, and the Illusion of Accountability

Defenders of the ₱1.19 trillion allocation often invoke the Commission on Audit (COA) as a safeguard.

This is only partially reassuring.

COA audits are typically post-facto, released years after funds are spent. Adverse Audit Observation Memoranda rarely translate into criminal convictions or administrative penalties. The Ombudsman, constitutionally independent though it is, remains institutionally overburdened.

The Supreme Court itself has acknowledged that accountability delayed is accountability diluted.

A trillion pesos flowing faster than enforcement mechanisms can keep up is not reform. It is risk transfer.

VI. Comparative Experience: Law Matters More Than Location

International experience reinforces this point.

Successful decentralization regimes—Germany, Canada, parts of Brazil—combine fiscal devolution with:

- statutory equalization mechanisms,

- professional civil services,

- transparent procurement systems, and

- aggressive audit institutions.

Failures—Nigeria, parts of Indonesia, several Latin American states—share a common flaw: money moved faster than institutions.

The Philippines appears perilously close to repeating that mistake.

VII. What the Law Requires—Not Merely Suggests

If the Marcos Jr. administration insists on devolving ₱1.19 trillion, the following are not policy preferences—they are legal necessities:

- Statutory performance standards, not merely DBM or DILG guidelines

- Mandatory real-time disclosure of projects, contractors, and costs

- Automatic funding suspensions for repeat COA violations

- Expanded resources for COA and the Ombudsman, or oversight becomes performative

Without these, decentralization risks violating the very principles—accountability, transparency, public trust—that Republic Act No. 6713 enshrines as binding law.

VIII. Conclusion: The Law Has a Long Memory

₱1.19 trillion is not just a budgetary choice. It is a legal gamble.

The Constitution permits decentralization.

The Supreme Court tolerates fiscal experimentation.

But the law is unforgiving when discretion becomes abuse.

- Budgets are forgotten quickly.

- Audit reports are read slowly.

- Court decisions arrive years later.

If this experiment fails, the courts will eventually assign responsibility. But by then, the classrooms will still be unfinished, the roads still half-paved, and the public once again told that the problem was implementation—not design.

The law, however, remembers both.

—–

Servant of the people, terror of the corrupt, and living legal headache,

–– Barok

(Still here. Still loud. Still right.)

Key Citations

A. Legal & Official Sources

- 1987 Constitution of the Philippines. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines.

- Mandanas v. Ochoa. G.R. Nos. 199802 & 208488, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 3 July 2018 Supreme Court E-Library.

- Pimentel Jr. v. Aguirre, G.R. No. 132988. Supreme Court of the Philippines [En Banc], 19 July 2000, Supreme Court E-Library.

- Belgica v. Ochoa. G.R. No. 208566, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 19 Nov. 2013, LawPhil Project.

- Araullo v. Aquino III. G.R. No. 209287, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 1 July 2014, LawPhil Project.

- Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. Republic Act No. 3019, Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, 17 Aug. 1960.

- Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees. Republic Act No. 6713, Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, 20 Feb. 1989.

- The Ombudsman Act of 1989. Republic Act No. 6770, Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, 17 Nov. 1989.

B. News Reports

- Simeon, Louise Maureen. “LGU budget rises to P1.2 trillion in 2026.” The Philippine Star, 13 June 2025.

- “LGU share of national taxes to total P1.19 trillion in 2026.” BusinessWorld, 28 Dec. 2025.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

- $2 Trillion by 2050? Manila’s Economic Fantasy Flimsier Than a Taho Cup

Leave a comment