Dream On, Pinas: Because Nothing Says “Living the Dream” Like a Trillion-Peso Interest Bill

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — January 16, 2026

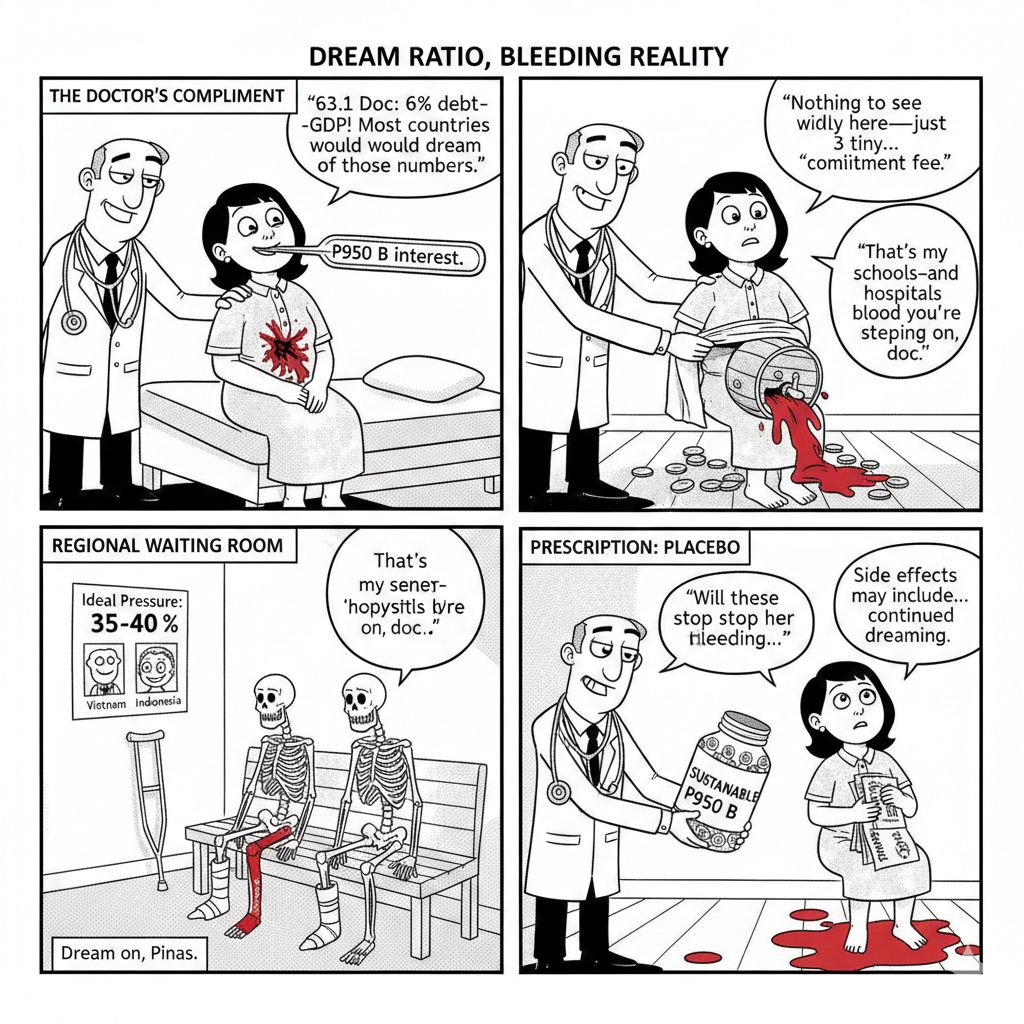

IMAGINE a doctor patting a patient on the back, declaring, “Most people would dream of your blood pressure readings,” while quietly noting that the patient is bleeding profusely from an untreated wound.

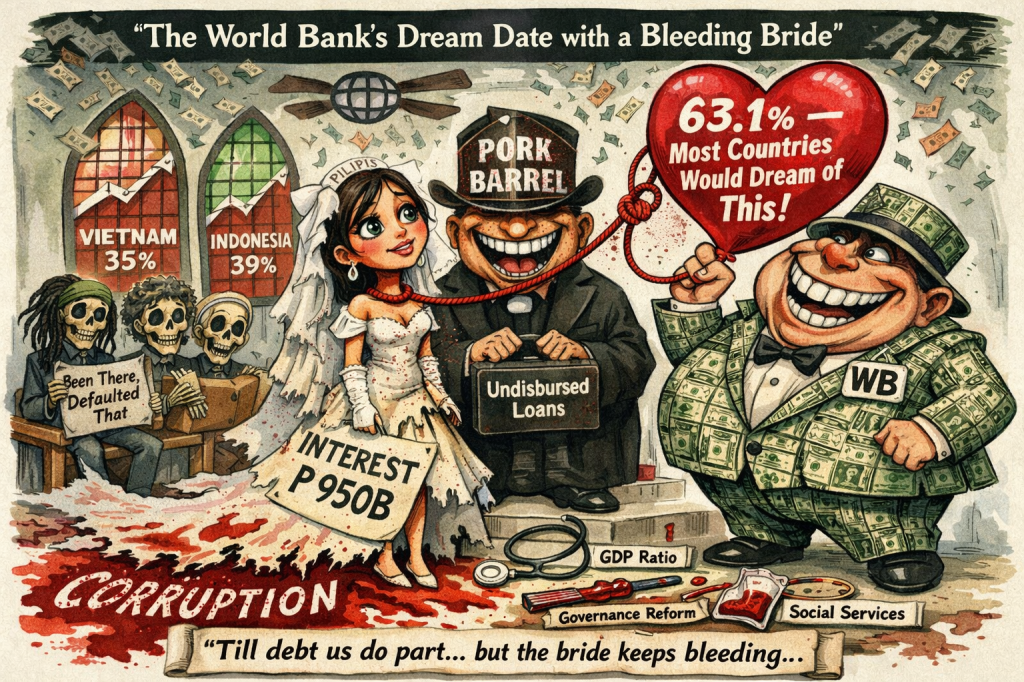

That, in essence, is the World Bank’s recent verdict on the Philippines’ public debt: enviable on paper, but quietly hemorrhaging from deeper afflictions.

In a BusinessWorld report published on January 11, 2026, World Bank (WB) Senior Economist Jaffar Al-Rikabi stated that the country’s debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratio—63.1 percent at the end of the third quarter of 2025—is something “most countries would dream of.” The absolute debt stock had reached a record P17.65 trillion as of November 2025. Interest payments alone are budgeted at P950 billion for 2026—nearly a trillion pesos that could otherwise fund schools or hospitals.

The WB projects the ratio peaking at 62.5 percent in 2026 before gradually declining to 61.4 percent by 2028. The bank calls the debt sustainable, pointing to its mostly long-term and peso-denominated character.

The reassurance sounds comforting—until you examine the fine print.

The Hollow Praise

The WB’s optimism hinges on ratios rather than absolute burdens and on debt structure rather than spending quality. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Philippines maintained a comfortable 40 percent debt-to-GDP ratio. The sharp rise since then is not merely a pandemic legacy; it reflects sustained borrowing overlaid on systemic inefficiencies.

More than P1 trillion in foreign loans remain undisbursed, accruing commitment fees while projects stall. The widely reported flood control corruption scandal—cited by Economic Planning Secretary Arsenio M. Balisacan as a direct drag on 2025 growth to possibly 4.8–5 percent—reveals the deeper problem: corruption functions as the single largest macroeconomic depressant in the country.

The bitter irony is clear. The WB praises vital signs while the wound—graft—continues to bleed.

Neighbors Tell a Different Story

A regional comparison quickly exposes the fragility of the “dream” narrative:

- Vietnam sustains a debt-to-GDP ratio of 33–38 percent, achieved through disciplined export-led growth and prudent fiscal policy.

- Indonesia holds steady at 38–40 percent, supported by commodity revenues and fiscal restraint.

- The Philippines, by contrast, has informally raised its “acceptable” threshold from 60 percent to 70 percent—a quiet concession to political realities over economic prudence.

Singapore is often invoked with its debt exceeding 160 percent of GDP, yet its obligations are largely asset-backed and serve to deepen sovereign reserves and financial markets. It is an outlier, not a valid peer.

Lessons History Keeps Teaching

Past debt trajectories offer sobering warnings:

- Jamaica reduced its debt from over 140 percent of GDP through rigorous primary surpluses, fiscal rules, and broad political consensus—a rare triumph of discipline.

- Greece and Sri Lanka followed the path of complacent projections and hidden vulnerabilities, ending in crisis: Greece endured a lost decade of austerity; Sri Lanka defaulted in 2022 at 94 percent debt-to-GDP, sparking economic collapse and social unrest.

The Philippines has not reached that brink, but the warning signs—rising nominal debt, escalating interest costs, and acknowledged governance failures—are unmistakable.

The Institutional Blind Spot

The WB’s Debt Sustainability Framework has long drawn criticism for its creditor-oriented metrics, emphasizing repayment ratios over investment quality or human development outcomes. Such assessments can inadvertently serve as marketing for continued lending rather than catalysts for genuine reform.

In the domestic arena, the WB’s positive verdict functions as a political shield, deflecting attention from administrative shortcomings. It creates a mutually assured delusion: the bank maintains its image as benevolent advisor, the government gains breathing room from public scrutiny, and the underlying disease—elite capture—progresses unchecked.

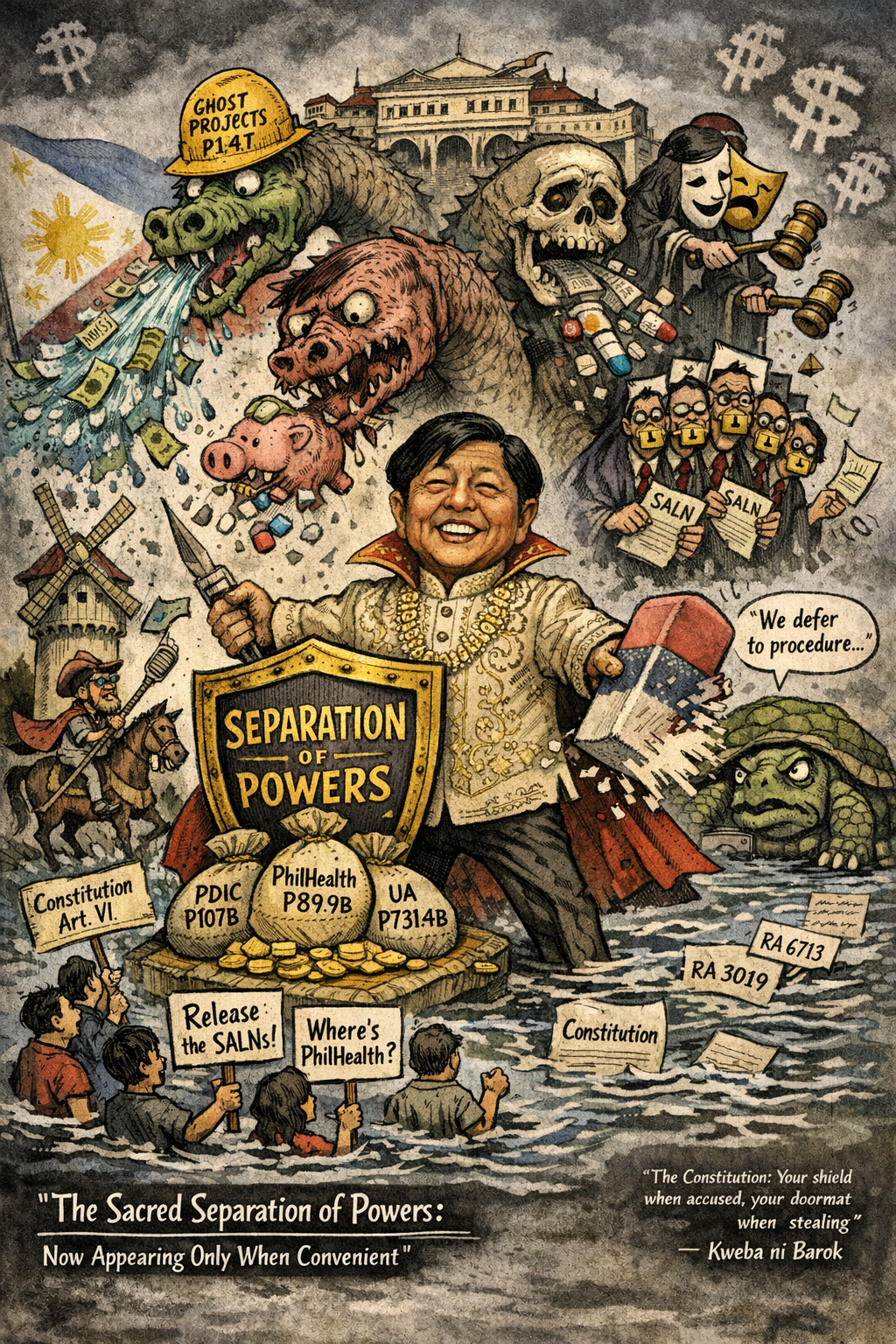

Corruption: The Core Virus

Corruption is not a peripheral issue in this debt discussion—it is the central pathogen.

Undisbursed loans generate fees without delivering projects. Flood control allocations disappear into inflated contracts, leaving communities more vulnerable to annual typhoons. Every peso diverted through graft is a peso denied to resilience, education, or poverty reduction.

In a nation where millions still lack adequate healthcare and schooling, truly sustainable debt becomes mathematically impossible when large portions of borrowing vanish before reaching the public.

The Paths Ahead

The WB-endorsed optimistic scenario assumes steady 5–6 percent growth, shrinking deficits, and interest payments that somehow do not crowd out essential spending. Yet unseen risks—global shocks, currency swings, or fresh scandals—could upend the projections.

Forced austerity, the alternative, would impose severe human costs without tackling the injustice of misappropriated funds.

Only one viable route exists: a fundamental revolution in governance.

Debt management must take second place to corruption eradication—through transparent procurement, independent oversight, and genuine accountability for the powerful. Revenue policy must prioritize taxing extreme wealth and closing elite loopholes rather than burdening ordinary citizens. Fiscal priorities must shift toward human capital—health, education, and climate resilience—over graft-laden megaprojects.

The Stark Choice

The World Bank insists most countries would envy our debt ratios.

But dreams cannot staunch bleeding wounds.

Filipinos deserve far more than an illusion. They deserve leadership that halts the hemorrhage and constructs a future grounded in reality.

Will the Philippines write a Jamaica-style recovery story, or become yet another cautionary tale of debt-fueled decline?

The decision belongs to us.

—

They say “sustainable.” Sabi Barok “suffer-table.” Enjoy the meal, mga boss. I go hunt truth.

- — Barok out… but never down

Key Citations

- Inosante, Aubrey Rose A. “‘Most Countries Would Dream of’ PHL Debt-to-GDP Levels, WB Says.” BusinessWorld Online, 11 Jan. 2026.

- “Gov’t Debt to Breach PHP 19T in 2026.” Wealth Insights, Metrobank / BusinessWorld, 13 Aug. 2025.

- “Indonesia’s Debt Ratio at 39.86 Percent of GDP, Still at Safe Level.” Antara News, 9 Oct. 2025.

- “Singapore Government Debt: % of GDP, 1990 – 2025.” CEIC, 31 Aug. 2025.

- “Vietnam Government Debt: % of GDP.” Trading Economics, 2025.

- Arslanalp, Serkan, et al. “How Did Jamaica Halve Its Debt in 10 Years?” Brookings, 11 Apr. 2024.

- “Greek Government-Debt Crisis.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 7 Jan. 2026.

- “Sri Lankan Economic Crisis (2019–2024).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 10 Jan. 2026.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment