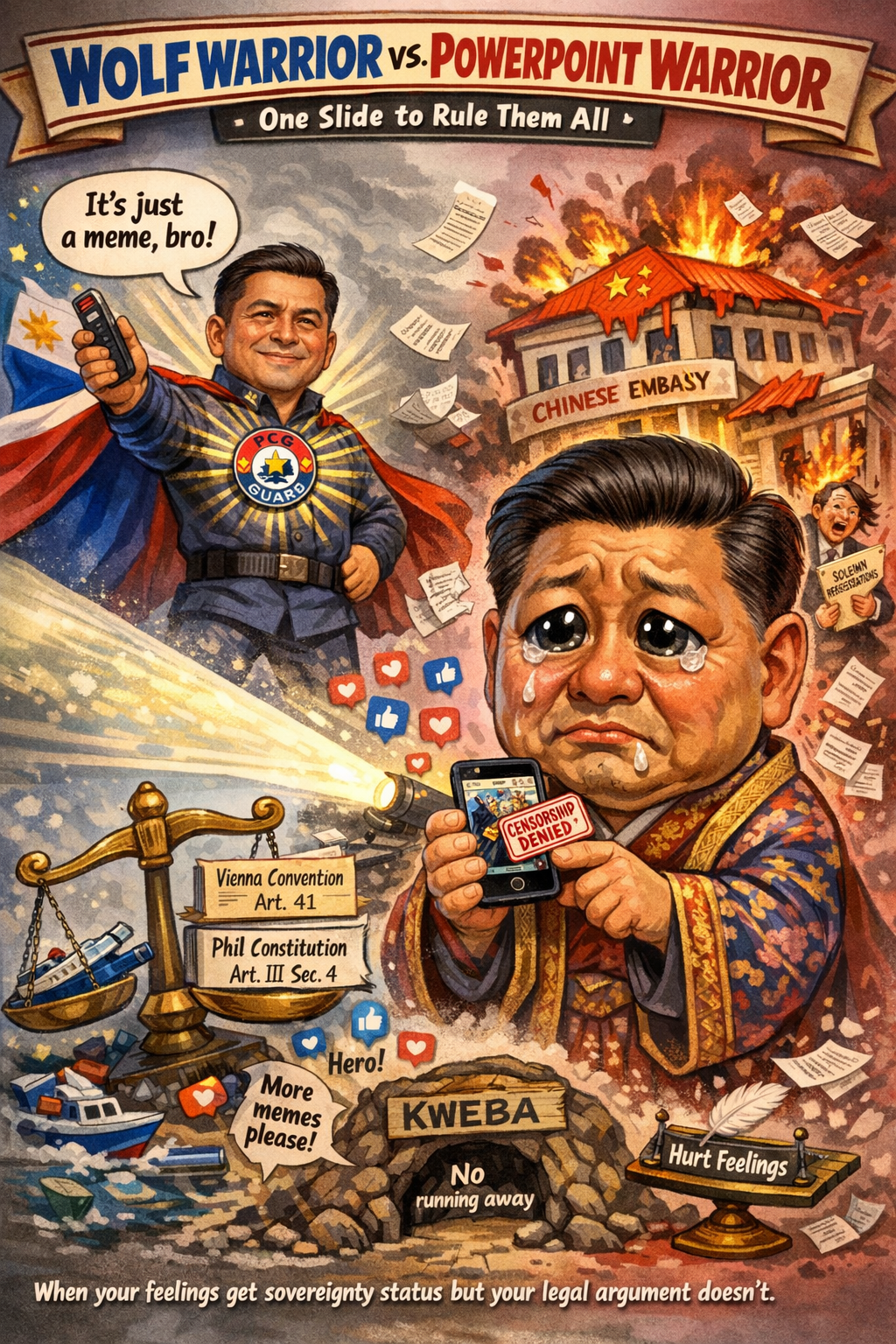

Beijing’s New Red Line: Thou Shalt Not Meme Our Dear Leader (Especially Not With Captions)

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — January 17, 2026

MGA ka-kweba, the West Philippine Sea is heating up again—not with water cannons this time, but with a single PowerPoint slide. Yes, just one slide. Three digitally altered photos of Xi Jinping that look like they were pulled straight from a Facebook meme page, captioned:

“Why China remains to be bully?”

Commodore Jay Tarriela, the Philippine Coast Guard’s (PCG) most outspoken voice on the West Philippine Sea (WPS), presented this during a university lecture. Suddenly, the Chinese Embassy exploded—filing “solemn representations” with Malacañang, the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA), and even the PCG itself. Their demand: “Hold him accountable” (Rappler, 16 Jan. 2026).

It feels like a movie plot. One satirical jab, instant diplomatic crisis. But behind the comedy lies a serious question: How far can a government official go in speaking out? And how far can a foreign embassy reach into our domestic affairs?

Let’s enter the cave. No running away.

1. The Core Contention: Wolf Warrior Diplomacy vs. Transparency Initiative

The real battle here is not personal—it is ideological and strategic.

On one side stands China’s Wolf Warrior Diplomacy—the new assertive brand of Chinese foreign policy that no longer hides behind polite diplomacy. Direct confrontation, public naming-and-shaming, and uncompromising defense of “national dignity.” On the other side is the Philippine transparency initiative: documented, timestamped, video-recorded, photo-evidence—everything released publicly so China can no longer plausibly deny the ramming, water cannoning, and laser blinding of Philippine vessels.

The satirical slide? It is a sharp extension of the transparency strategy. Not a formal diplomatic note. This is meme warfare. And in the age of social media, the meme has become a weapon.

My critique:

China is wrong to treat a clearly satirical slide as a “serious violation of political dignity.”

If every caricature of Xi in Western media triggered a formal protest, they would have no time left for anything else. But Tarriela—or at least his choice—was also risky. Using the face of a foreign head of state in this manner is not universally amusing, especially coming from a uniformed officer subject to stricter decorum expectations. Edgy? Yes. Necessary? Debatable. Effective? Undeniably.

In the end, though, the slide is only a symptom. The disease is China’s continued coercion inside our exclusive economic zone.

2. Legal Thunderdome: Vienna Convention vs. Bill of Rights

This is where the fight gets really interesting.

Chinese Embassy’s position: “Crossed the red line.” “Blatant political provocation.” “Hold accountable.” Translation: They want us to discipline our own official because Xi’s feelings were hurt.

Legal footing? Paper-thin. Article 41(1) of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (1961) requires diplomatic missions to respect the laws of the receiving state and not interfere in its internal affairs. Demanding that the host country punish one of its own officials for speech is textbook interference. This is not “solemn representation”—this is attempted coercion.

Tarriela’s position:

“This is interference. I am reporting facts. Satire is protected speech.”

Legal footing? Solid under the 1987 Constitution, Article III, Section 4: “No law shall be passed abridging the freedom of speech…” The Supreme Court in Chavez v. Gonzales and related cases has been clear: any prior restraint or punishment of speech must satisfy the “clear and present danger” test. Does a meme slide pose an immediate danger? None whatsoever. Even as a public official, Tarriela is protected under the Borjal v. Court of Appeals doctrine when commenting on public figures and matters of public concern—especially without actual malice.

Republic Act No. 6713 (Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees) and PCG regulations? They could theoretically support an internal reprimand if the conduct was grossly inappropriate, but this is not criminal, and certainly not sufficient grounds to capitulate to foreign pressure. Likewise, Republic Act No. 9993 (Philippine Coast Guard Law of 2009) establishes the PCG’s mandate but does not prohibit factual reporting on maritime incidents.

Verdict: Tarriela’s defense stands on far stronger legal ground than China’s complaint. Still, the real question remains: Was satire necessary? Sharp facts alone might have sufficed.

3. Pathways & Precedents

If the Philippines caves and punishes Tarriela:

- Internal PCG disciplinary proceedings → reprimand or suspension

- Ombudsman complaint → alleged violation of professionalism

- Political cost: Enormous. The government would appear weak in the eyes of a public already furious at China.

If the Philippines stands firm:

- Precedent: Strong defense of sovereign speech and transparency

- Chilling effect? Reversed—it could embolden other officials to speak out

Counter-options against the Embassy? Severely limited. Diplomatic immunity protects them. Possible counter-protest, reduced engagement, summoning Ambassador Jing Quan for “clarification.” But arrest or expulsion? Not realistic without extreme justification.

4. Strategic Chessboard

Malacañang & DFA: Smartest current play? Strategic silence + tacit backing for Tarriela. Avoid giving the issue oxygen through an official statement that might signal doubt about the transparency initiative. Behind closed doors, however, they can remind China: “We respect diplomatic norms. You should too.”

PCG / Tarriela: Continue documentation, but calibrate tone. Facts first, satire second. Better coordination with DFA to avoid appearing as a lone ranger.

Chinese Embassy: Major strategic miscalculation. Instead of intimidating Tarriela, they’ve turned him into even more of a national hero. In the social media age, wolf warrior tactics frequently backfire with neutral audiences.

Best resolution: Managed dispute anchored firmly in the rule of law—return the conversation to the 2016 UNCLOS Arbitral Award. No personal attacks, no memes, no public shaming—pure legal and diplomatic channels.

5. Consequences & Fallout

If this rhetorical escalation continues:

- Bilateral relations: Colder still. Trade talks, investments, and joint projects become even harder.

- Domestic politics: Anti-China sentiment rises further. Nationalist politicians gain ground.

- Transparency strategy: If spokespersons become afraid, we lose our most effective non-kinetic weapon against gray-zone tactics.

- International diplomacy: The line between legitimate protest and interference blurs. China risks leading the list of nations using embassies to suppress criticism of their leaders.

Final Recommendations (No Sugarcoating)

To the Philippines:

- Do not punish Tarriela. Give full backing to the transparency initiative.

- File a counter-protest against the Embassy for violating Article 41.

- Develop clear guidelines for public communication by uniformed personnel—not to silence them, but to protect them.

- Return maritime discussions to the 2016 Arbitral Award and UNCLOS framework. No concessions on sovereignty.

To China:

- Stop the wolf warrior overreach. Public statements will not intimidate us.

- If you truly want “mutual trust,” respect our rights in our EEZ and our right to speak about them.

Friends, in the end, a satirical slide will not start a war. But surrendering to foreign pressure to silence our own speech? That is the real red line.

Until the next chapter in the West Philippine Sea.

— Barok

(Still breathing free Philippine air, no embassy permission required.)

Key Citations

A. Legal & Official Sources

- Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. 18 Apr. 1961, United Nations, Supreme Court E-Library.

- The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, 1987.

- Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees. Republic Act No. 6713, Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, 20 Feb. 1989.

- Philippine Coast Guard Law of 2009. Republic Act No. 9993, Chan Robles Virtual Law Library, 15 Jan. 2010.

- Chavez v. Gonzales. G.R. No. 168338, Supreme Court E-Library, 15 Feb. 2008.

- Borjal v. Court of Appeals. G.R. No. 126466, LawPhil Project, 14 Jan. 1999, LawPhil Project.

- Permanent Court of Arbitration. “The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China).” PCA-CPA, 12 July 2016.

B. News Reports

Leave a comment