Because Nothing Says “Good Governance” Like Keeping the Bagman on Payroll

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — January 19, 2026

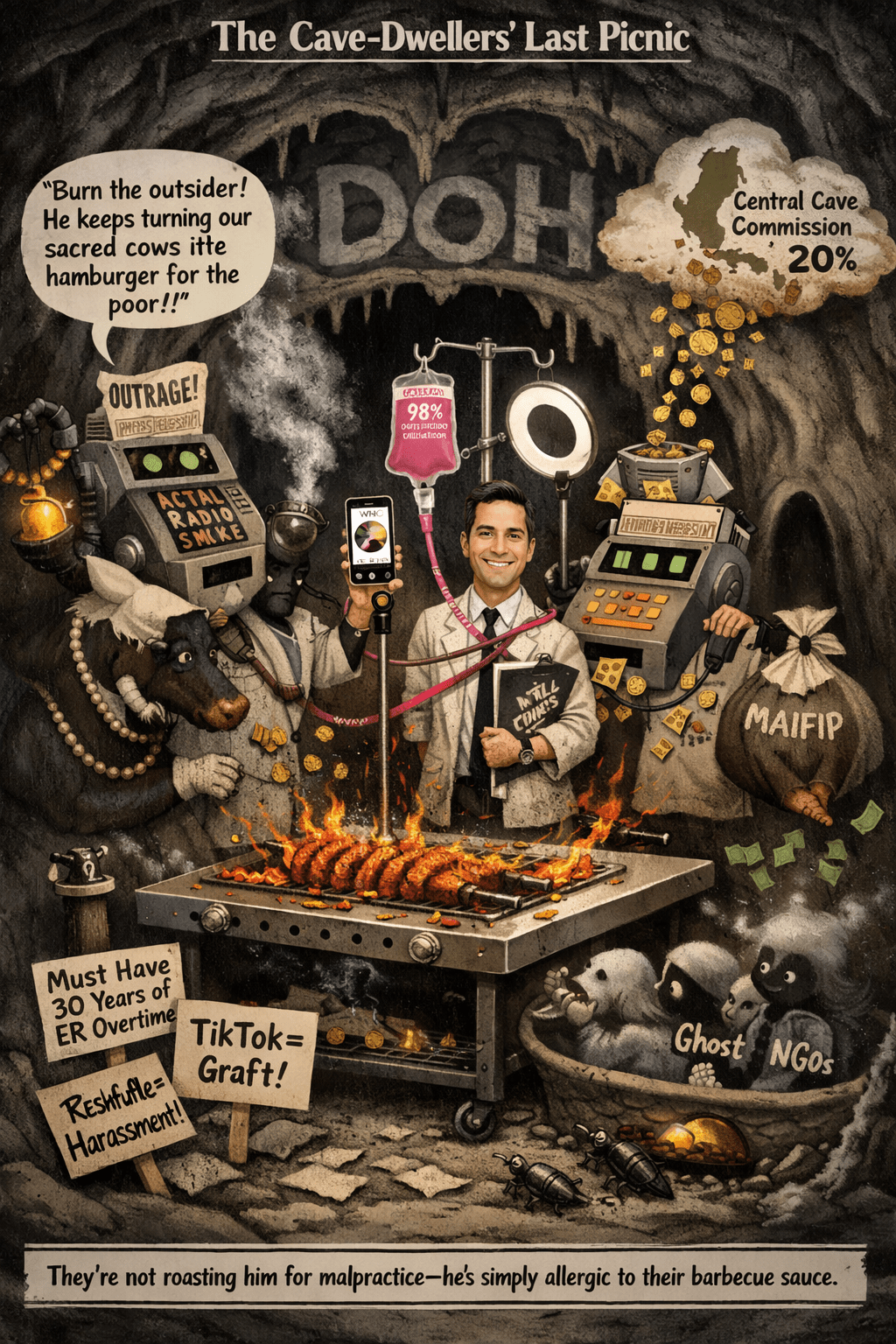

MGA ka-kweba, welcome back to the cave. Today the stench in here isn’t mold and dampness—it’s the unmistakable smell of public funds being quietly divided up in Ilocos Norte while the rest of our provinces continue to drown in floodwaters. And right in the middle of it all, Justice Undersecretary Jose “Jojo” Cadiz Jr. silently returned to his desk on January 5, 2026. No fanfare. No explanation. Just another ordinary day in Malacañang.

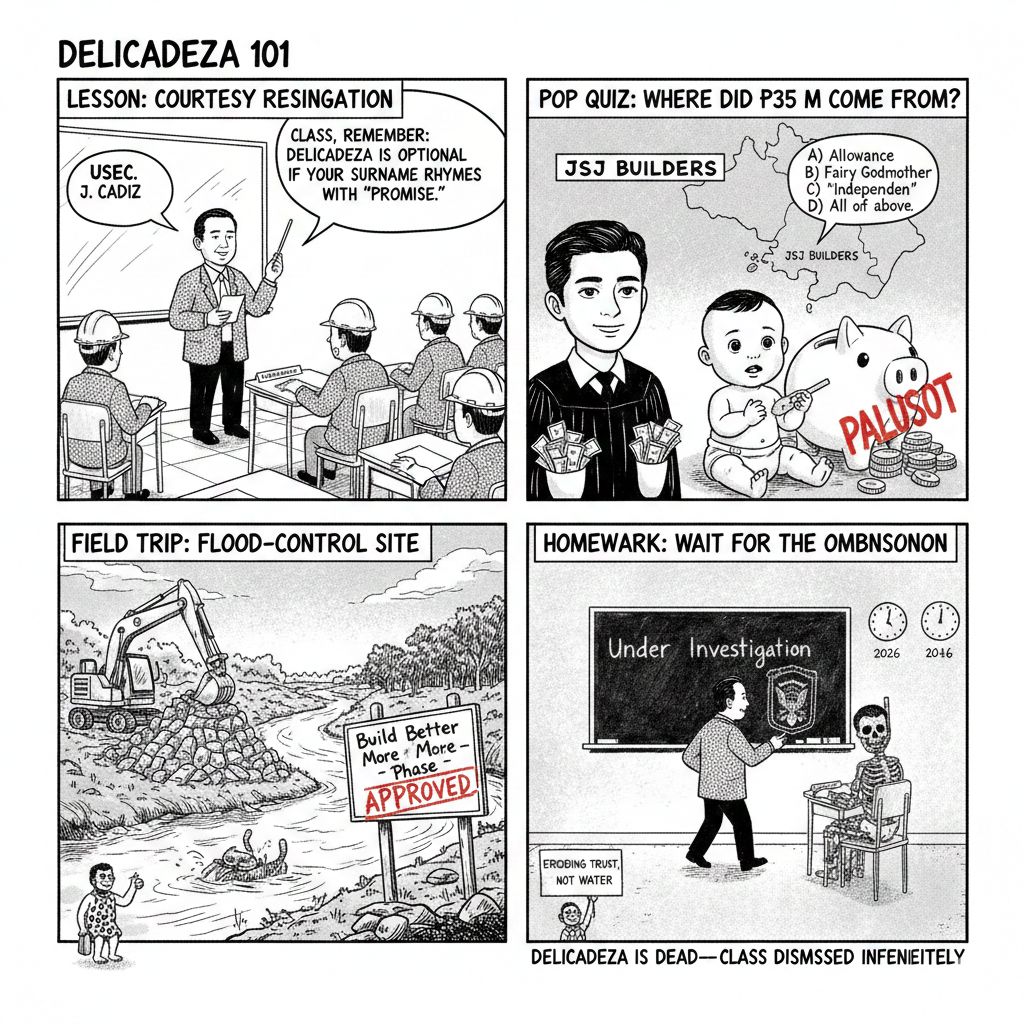

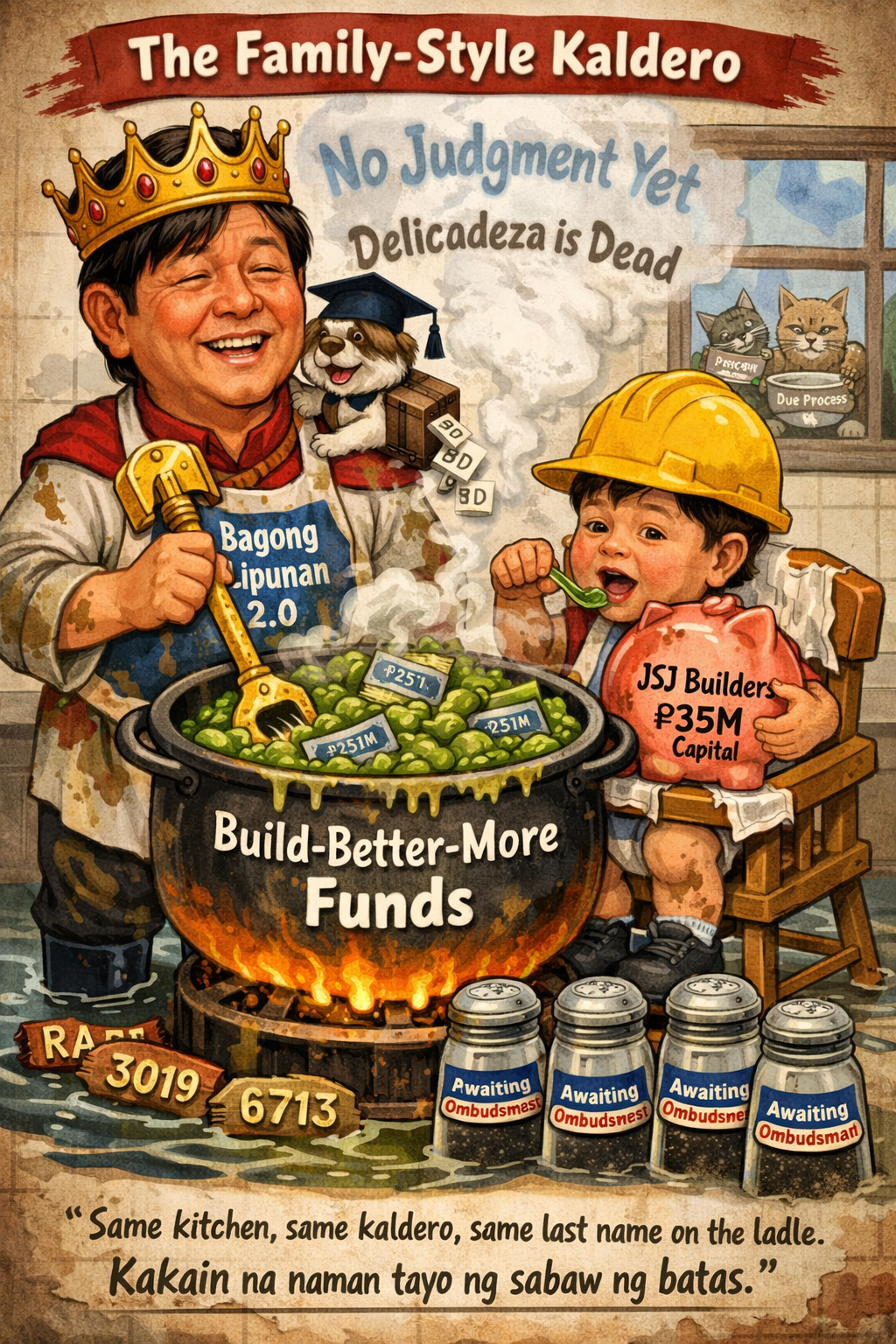

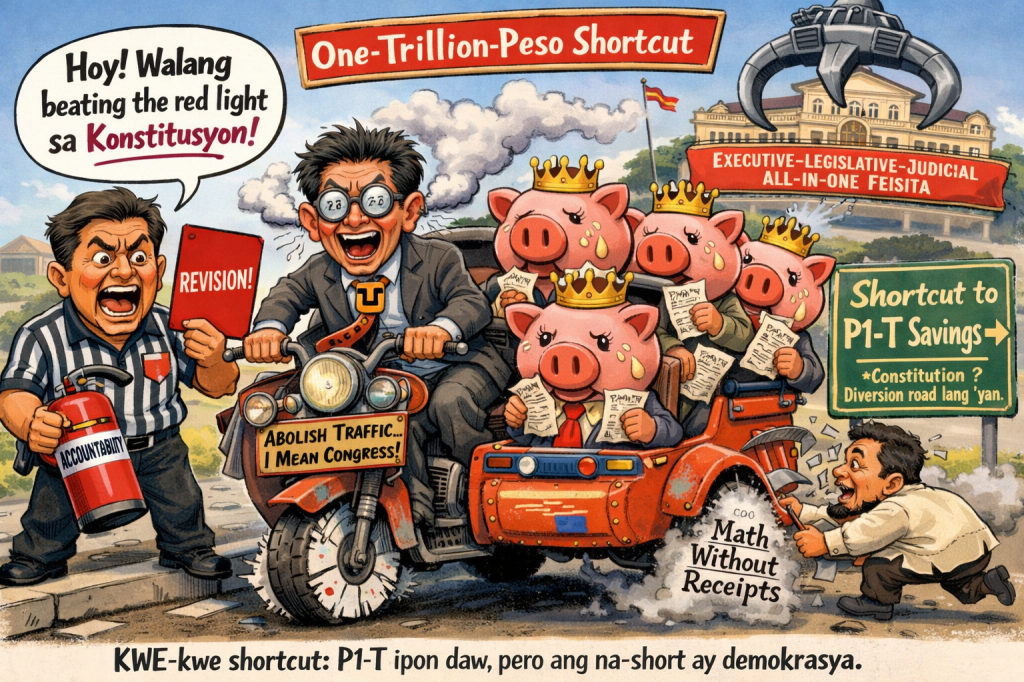

President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the very leader who promised us “Bagong Lipunan 2.0,” rejected the courtesy resignation of his fellow Ilocano and long-time aide. Why? Because there is supposedly “no judgment yet.” Because resignation is merely a matter of “delicadeza.” Because… well, because Cadiz is still supposedly needed at the Department of Justice (DOJ). Meanwhile, his 19-year-old son owns a construction company that has already secured ₱251 million worth of flood-control and road projects—all located in Ilocos Norte. All of this while Cadiz sat as undersecretary.

This is not an accident. This is not “lucky business.” This is classic Philippine political theater—and the script was written during the time of Marcos Sr. As detailed in Rappler’s investigative report: Marcos keeps contractor-linked Cadiz in DOJ.

The Constitutional Blood in the Water

First, let us be very clear about the law—because Malacañang appears to have conveniently forgotten it.

The 1987 Constitution—the same document they wave around every election season to boast about “people power”—is crystal clear. Article XI, Section 1 declares: Public office is a public trust. And Article XI, Section 13 states unequivocally that no Cabinet member or deputy (including undersecretaries) shall have any direct or indirect financial interest in any government contract.

Indirect. Not just Cadiz’s own pocket. The prohibition includes family members. It includes a 19-year-old son who suddenly had ₱35 million in capital to establish JSJ Builders in 2023—the exact year his father was already sitting as DOJ undersecretary.

And the punchline? A brand-new company, barely incorporated, immediately wins hundreds of millions in contracts—all in Ilocos Norte. All flood control and road projects. All in the home province of both Marcos and Cadiz. Isn’t that adorable? A college student suddenly becomes a construction tycoon. Like a fairy tale—if the fairy godmother’s name is “political connection.”

But this is no fairy tale. This conduct violates:

- Republic Act No. 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act), particularly Section 3(h) (having financial interest in a transaction connected with one’s office) and Section 3(e) (causing undue injury or giving unwarranted benefits);

- Republic Act No. 6713 (Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees), which requires divestment of conflicting interests and avoidance of the appearance of impropriety;

- Republic Act No. 9184 (Government Procurement Reform Act), which is supposed to guarantee fair and transparent bidding.

The Supreme Court, through doctrines consistently applied in cases involving indirect interest via relatives, has long held: when your child is the contractor and you are the high-ranking official, there is a presumption of indirect financial interest. No need to prove actual kickbacks. The situation itself is already constitutionally offensive.

Yet the Palace response remains: “Let’s wait for the Ombudsman.” Classic delay tactic, straight out of the Crony Playbook, Chapter 1.

The Defense Playbook: Same Old Script, Same Old Lies

Here are the expected defenses—and why they collapse under the slightest scrutiny:

- “There is no proof yet. No direct intervention.”

Right. And Santa Claus really delivers the presents. The Constitution does not require a smoking gun. The mere appearance of impropriety is sufficient to trigger concern. But in the Philippines, when you are a loyalist, they demand a video confession before you can be held accountable. - “My son is an independent adult.”

An independent adult who magically had ₱35 million in capital while still a student? Where did that money come from—heaven? Or the political machinery of Ilocos? And why are all the projects located in the home province? Pure coincidence, of course. - “Zaldy Co is a fugitive; he is not credible.”

True, Co is in hiding and his allegations came via Facebook videos. But why did he feel the need to post videos? Because he knows that surrendering might earn him the “Salvador Panelo” special. Even without a sworn statement yet, the Ombudsman has already opened a fact-finding investigation—based on the Rappler reporting alone. - “It was only a courtesy resignation; it wasn’t serious.”

In December, Malacañang announced that all officials with contractor links should submit courtesy resignations. Many did. But Cadiz? Special exemption. Delicadeza for thee, but not for me.

This is the selective delicadeza we have come to know so well: opposition figures are presumed guilty on rumor alone; friends of the Palace are given the benefit of endless “due process.”

Marcos’s Calculated Bet: Loyalty Over Law

It was no accident that Marcos rejected the resignation. This was a deliberate political risk. Cadiz has been a trusted aide since the days when Bongbong was still a senator. He is the quintessential “trusted insider.” In a presidency already battered by family dramas and political crises, Marcos apparently decided that retaining a loyalist who knows too much was worth the credibility damage.

The price? The entire “Build Better More” infrastructure program now carries the stain of suspicion. When the public sees flood-control money flowing to the children of officials, how can anyone still believe there has been real change?

This is a rerun of familiar scandals: the Jose Pidal accounts under Arroyo, Estrada’s jueteng, the ghost projects of previous administrations. The pattern never changes: power + proximity = profit.

What Next? The Ombudsman and the People

The Office of the Ombudsman has already launched a fact-finding investigation. This is the principal pathway forward. If probable cause is established, Cadiz can face criminal charges before the Sandiganbayan for graft and violation of anti-conflict-of-interest laws. But we all know the reality in the Philippines: justice moves slowly when the accused is powerful.

Meanwhile, the damage is already visible:

- Erosion of public trust in the entire infrastructure program

- Damage to the credibility of the Department of Justice itself

- International perception of yet another administration mired in corruption

The Call: This Cannot Go On Forever

Fellow citizens, “waiting for the Ombudsman” is no longer enough. We demand:

- Full transparency — release all bidding documents, financial trails, and contracts awarded to JSJ Builders.

- Swift and fearless investigation — let the Ombudsman follow the evidence wherever it leads.

- Real reforms — enact an absolute ban on government contracts awarded to relatives of high-ranking officials, and strengthen procurement safeguards.

- Accountability from the President — remove Cadiz. Show the nation that the law applies equally to everyone.

Cadiz is not just one man. He is a symptom of the disease that has long infested Malacañang: the belief that loyalty ranks higher than the law.

As long as we allow this to continue, we will remain drowning—not only in floodwaters, but in corruption.

From the depths where the truth still stinks worse than the politics above,

–– Barok

(still breathing, still disgusted)

Key Citations

A. Legal & Official Sources

- Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. Republic Act No. 3019, Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, 17 Aug. 1960, http://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1960/08/17/republic-act-no-3019/.

- Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees. Republic Act No. 6713, Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, 20 Feb. 1989, http://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1989/02/20/republic-act-no-06713/.

- Government Procurement Reform Act. Republic Act No. 9184, Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, 10 Jan. 2003, http://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2003/01/10/republic-act-no-9184/.

- The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, http://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/constitutions/the-1987-constitution-of-the-republic-of-the-philippines/the-1987-constitution-of-the-republic-of-the-philippines-article-xi/.

B. News Reports

Leave a comment