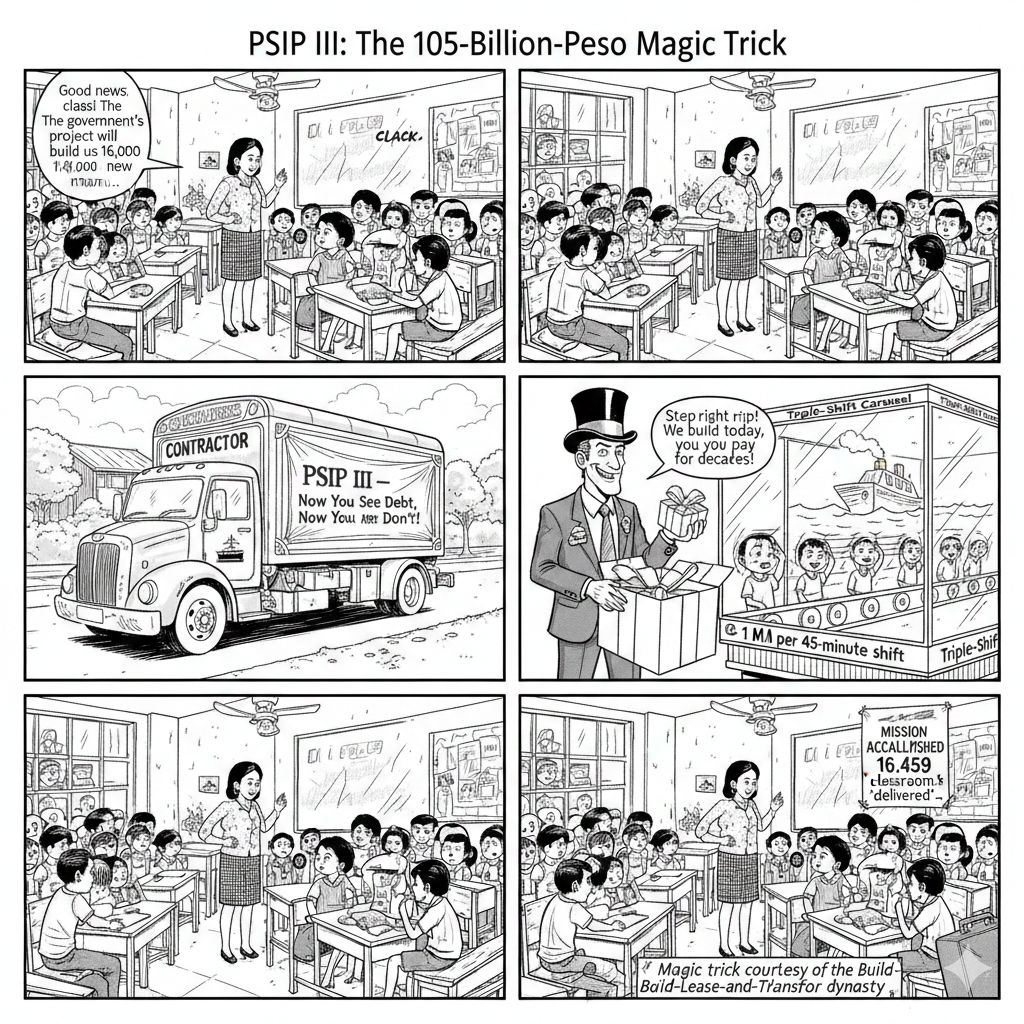

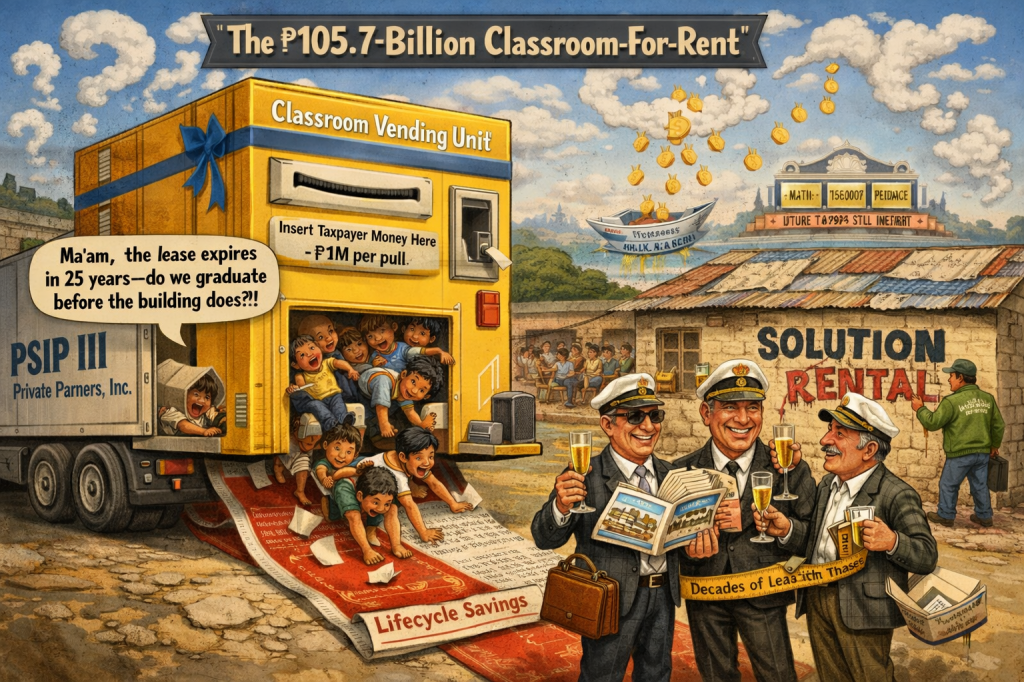

₱105.7 Billion Later, the Children Still Study in Shifts — But the Contractors Study Yacht Catalogs

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — January 21, 2026

IN A typical Manila public school—not far from the gilded halls of Malacañang—fifty children cram into a room designed for thirty. They share dog-eared textbooks, sweat through triple shifts, and strain to hear lessons over the roar of jeepneys outside. This is the daily reality for millions of Filipino learners.

Now comes the grand announcement: a ₱105.7-billion project to build 16,459 new classrooms, directly benefiting 800,000 students annually and reducing average class sizes from 50 to 39. Education Secretary Sonny Angara calls it a “whole-of-nation approach.” President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., who chaired the approving council, has ordered a “greenlane” to fast-track it.

It sounds like salvation.

But look closer, and the promise flickers. Those 16,459 classrooms represent barely one-tenth of the acknowledged 165,000-classroom backlog—a backlog that has festered for decades despite annual budget promises. PSIP III is not a breakthrough. It is a single, extravagantly priced chisel struck against a mountain of systemic neglect.

The real question is not whether more classrooms are needed—we all know they are—but whether this chisel is sharp, honest, and wielded by trustworthy hands.

The Political Architecture

Secretary Angara, newly installed amid a department in disarray, presents the PPP as one of several “horses in the race.” President Marcos, ever attentive to legacy-building projects, blesses it with expedited status.

On the surface, this looks like decisive leadership. Yet both men oversee a government whose traditional infrastructure pipeline remains clogged with delays, incomplete projects, and vanishing funds. Angara himself has admitted that more than 1,000 classrooms built by the Department of Public Works and Highways remain unfinished or unusable.

The “greenlane,” then, resembles less a burst of visionary urgency and more a detour around the clogged arteries of regular budgeting and procurement—arteries clogged, in part, by the very political and bureaucratic cultures these leaders inherit and, so far, sustain.

When public investment has been chronically underfunded and mismanaged, turning to the private sector may feel innovative. But it can also look like an admission of defeat: the state cannot—or will not—do the job itself.

Panacea or Peril?

Proponents insist PPPs deliver what the public sector cannot: speed, efficiency, and expertise. The numbers are seductive:

- Projected ₱40.15 billion in lifecycle savings

- More than 57,000 jobs created

- Construction potentially starting as early as March 2027

Private partners bear upfront costs and maintain buildings during the lease period, theoretically aligning profit motives with quality.

Yet the model is Build-Lease-and-Transfer (BLT). The government does not own the classrooms until the lease expires—potentially decades later—while making regular payments along the way. Those payments are not free money; they are a deferred fiscal burden passed to future administrations and taxpayers. If the vaunted “savings” prove illusory, the country will have paid a premium for the privilege of renting its own schools.

History offers little comfort. PSIP Phases I and II delivered 13,391 classrooms but stumbled over delays, permit bottlenecks, abandoned contracts, and inaccessible sites. The same department now promises the largest classroom PPP in Philippine history will avoid those pitfalls. Skepticism is not cynicism—it is prudence.

The Corruption Crucible

Large infrastructure contracts in the Philippines have long been fertile ground for graft. The PPP structure, for all its technical sophistication, does not inoculate against familiar pathologies; in some ways, it multiplies them.

- Procurement rigging: Tailored terms of reference, selective pre-qualification, or collusive bidding can still steer contracts to politically connected conglomerates.

- Quality shell game: Private builders responsible for maintenance during the lease have every incentive to cut corners with materials that pass initial inspection but degrade quickly—securing future repair revenue while the buildings remain under their care. After handover, the public inherits the consequences.

- Oversight theater: Monitoring falls to the PPP Center, DepEd, and ADB technical assistance—respectable institutions on paper. Yet Republic Act No. 11966, the Public-Private Partnership Code of the Philippines while improved, still relies heavily on agency self-policing and Commission on Audit reviews whose enforcement has historically been uneven.

When billions are at stake, encouragement is not enough. Independent, empowered oversight is.

A Sick System Seeking a Private Cure

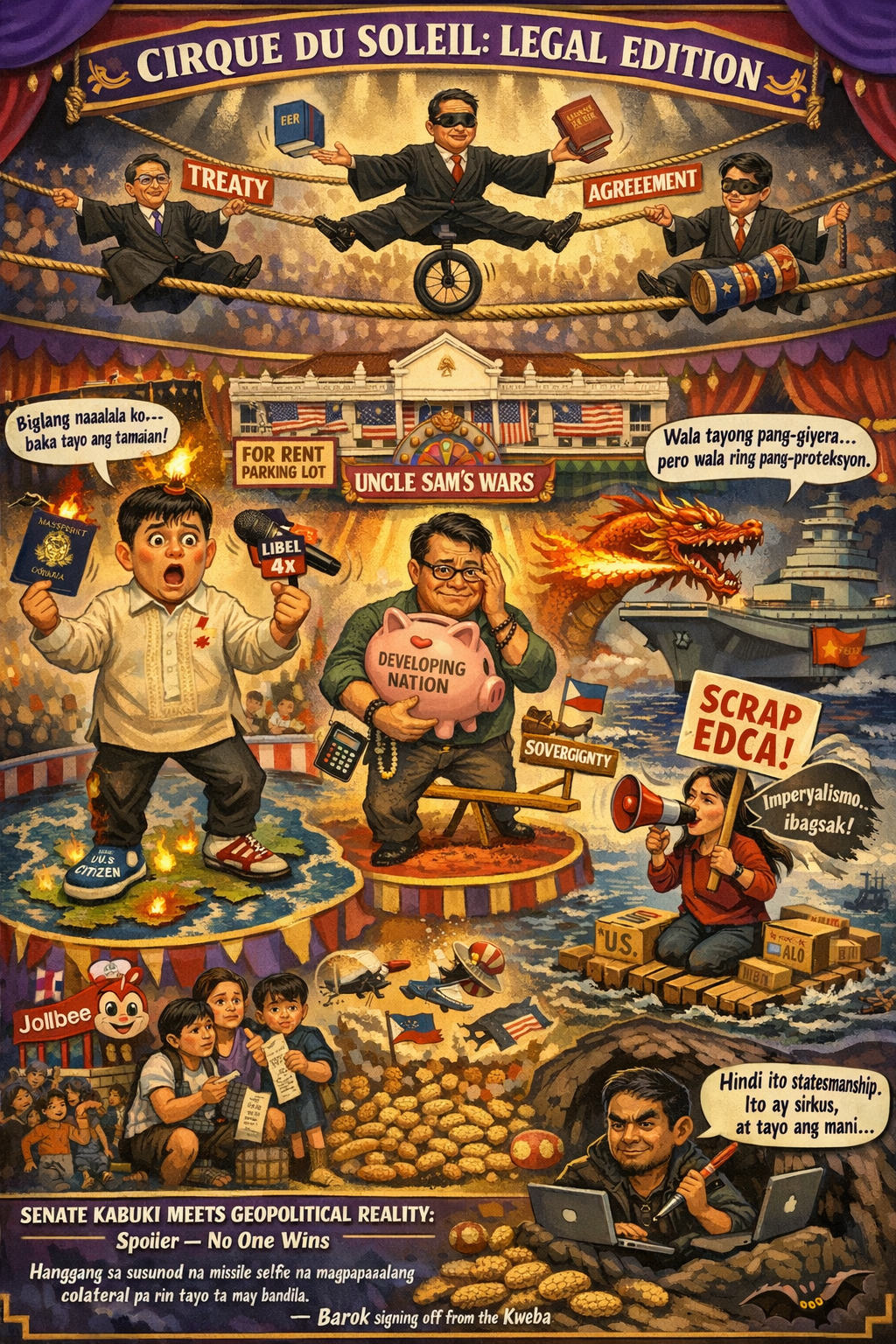

This project launches amid a broader crisis of confidence in public works. Recent scandals—billions allegedly diverted through ghost projects, midnight insertions, and rigged awards—have shaken investor faith and dragged on growth.

The ecosystem into which PSIP III steps is one where systemic corruption “continues to hamper the delivery of public services,” as international observers politely phrase it. The new PPP Code introduces stronger transparency rules and criminal penalties. These are welcome steps. But laws are only as strong as the political will to enforce them—and that will has often been found wanting when powerful networks benefit from opacity.

Lessons from Elsewhere

Other nations have walked this path:

- Britain’s Private Finance Initiative delivered schools faster but saddled taxpayers with decades of inflated payments—eventually costing far more than conventional borrowing.

- Pakistan’s Sindh program improved test scores in adopted schools yet struggled with sustainability once private contracts ended.

The consistent lesson: PPPs can work when wrapped in ferocious transparency, independent audit, and political insulation from crony interests. The Philippines has rarely managed all three at once.

Demands, Not Mere Applause

No sensible observer opposes building classrooms. The issue is how, and at what cost to integrity and equity.

The public deserves more than press releases and ribbon-cutting timelines. We must demand:

- Full, real-time online disclosure of pre-qualification shortlists, bid documents, evaluation matrices, final contracts, and every lease payment schedule—no redactions except those narrowly justified and judicially reviewed.

- Empowered third-party monitoring by credible civil-society coalitions with site access, document rights, and authority to trigger independent audits.

- Automatic criminal triggers for any irregularity, prosecuted by an insulated special unit rather than channels prone to political pressure.

- Binding equity commitments ensuring remote, poorest, and disaster-prone areas are not sidelined for urban clusters more profitable to private builders.

Ultimately, PPPs are tools, not cures. The constitutional duty to provide free, quality public education remains the state’s—not a consortium’s. If leaders truly wish to break the cycle of overcrowded classrooms, they must pair this expensive experiment with a ruthless, sustained campaign to:

- Dramatically boost direct public investment

- Eradicate graft at its roots

Otherwise, we may get new buildings—perhaps on time, perhaps not—but built on foundations as shaky as the political will that conceived them.

And the children sweating in today’s overcrowded rooms will still be waiting tomorrow.

Sealed with the righteous indignation of a taxpayer who still remembers what free public education was supposed to mean,

— Barok

The One Who Refuses to Lease His Principles

Key Citations

A. Legal & Official Sources

B. News Reports

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

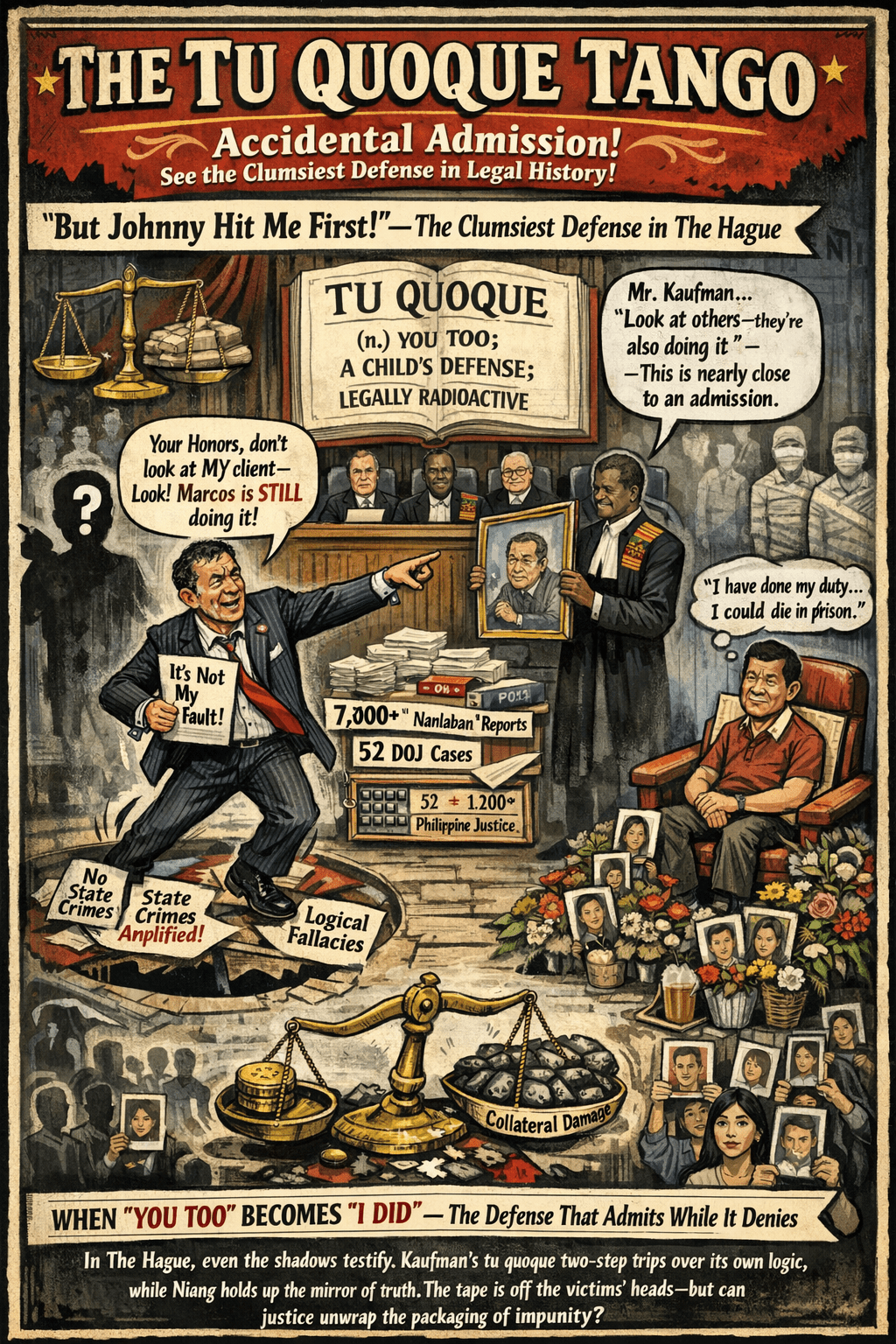

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment