When “Strict Compliance” Becomes Code for “Sorry, Marcos Is Busy”

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — January 26, 2026

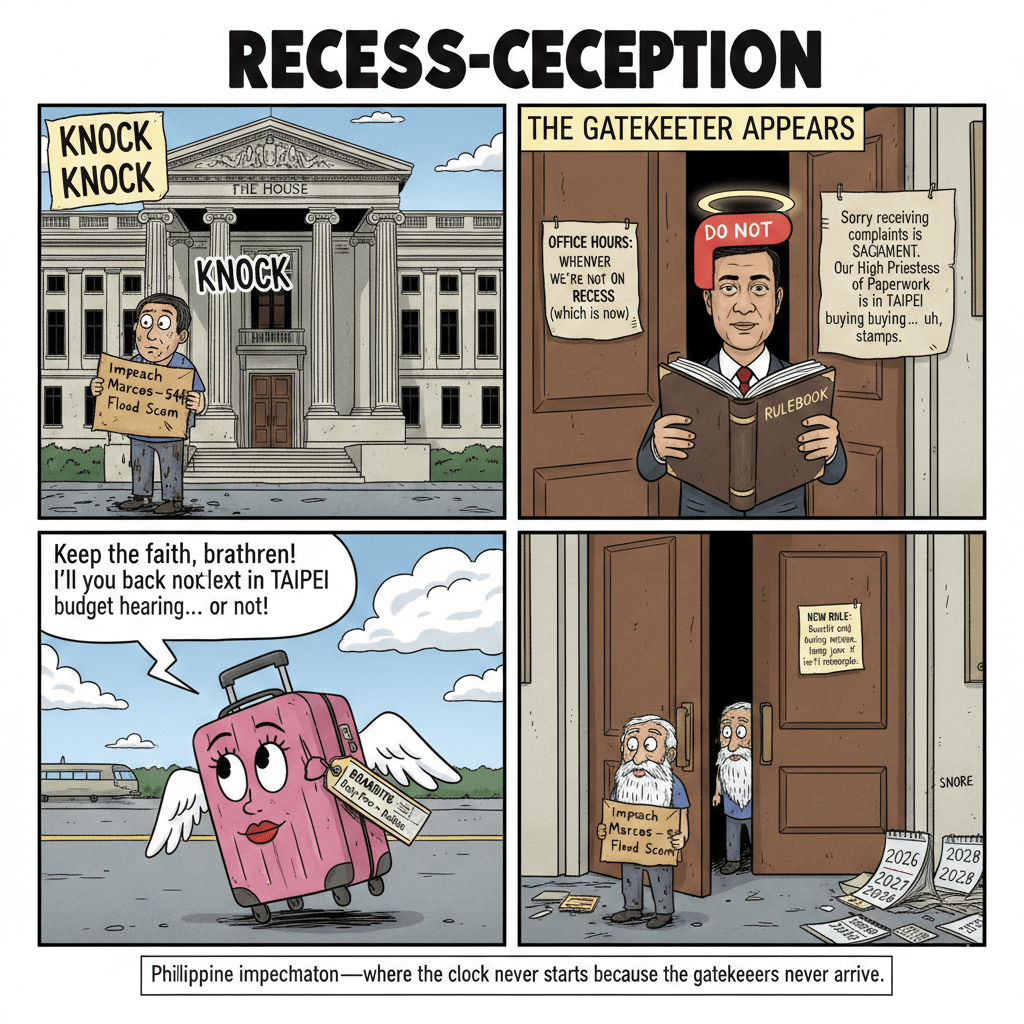

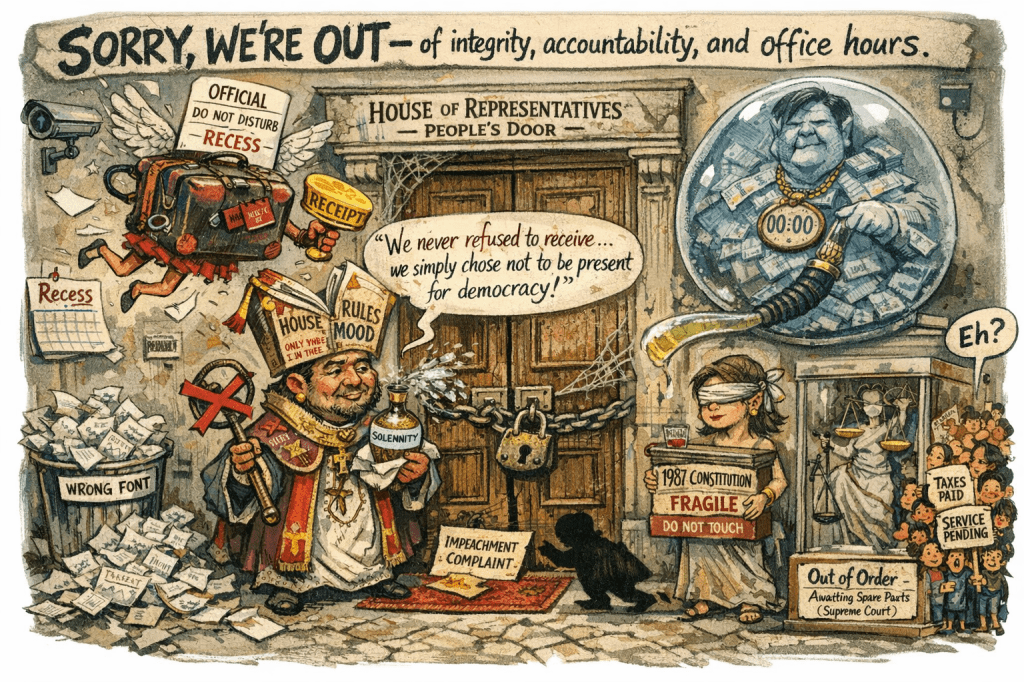

BEHOLD, the Philippine House of Representatives—bastion of the people’s will, or so the fairy tales go. In a plot twist worthy of a bad teleserye, they’ve unveiled their latest innovation in governance: the “Sorry, We’re Out” shield against presidential scrutiny. Picture this: impeachment complaints against President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. arrive at the doorstep, only to be met with the constitutional equivalent of a “Do Not Disturb” sign because Secretary General Cheloy Garafil is off on some “official overseas engagement.” Rep. Zia Alonto Adiong, the self-appointed Pontiff of Procedure, swoops in with a defense straight out of a bureaucratic fever dream, insisting this is all about “safeguarding the solemnity of the process.” Let’s dust off our legal scalpels and a hefty dose of cynicism, and carve up this farce to see what’s really being protected: not the Constitution, but the cronies in power.

The Procedural Charade: Drop-Off Democracy on Hold

Let’s start with the absurdity Adiong peddles as wisdom. He proclaims that receiving an impeachment complaint isn’t a “casual or clerical transaction” but a “formal constitutional act” demanding the Secretary General’s personal touch. Oh, the grandeur! One can almost hear the orchestral swell as Garafil, the Peripatetic Custodian of Records, is invoked like some absent deity.

But strip away the pompous verbiage, and what’s left? A mundane filing turned into a high-stakes game of musical chairs, where the Republic’s accountability grinds to a halt because one official is gallavanting abroad during recess.

Mockery aside—though it’s richly deserved—ask yourself: Is our vaunted impeachment mechanism so brittle that it shatters at a “drop-off”? Adiong’s logic implies yes, reducing Article XI of the 1987 Constitution to a suggestion rather than a command. The House Rules he clutches like a talisman specify receipt by the Secretary General for verification of completeness, endorsements, and form. Fair enough, but what happens when she’s AWOL? Apparently, nothing. This isn’t prudence; it’s a procedural pantomime designed to evade action. In the “Great Receipt Standoff,” democracy waits politely while the “Walk-In That Wasn’t” exposes how the House treats constitutional duties like an optional errand.

Constitutional Vivisection: House Rules vs. the Supreme Law

Now, let’s pit Adiong’s beloved House Rules against the unyielding steel of the 1987 Constitution—and watch the rules crumple. Article XI, Section 1 declares public office a public trust, demanding accountability from officials like Marcos amid the festering flood control fund scandal, where billions allegedly vanished into fake projects and allied pockets. Section 3(1) grants the House exclusive power to initiate impeachment, with Section 3(2) allowing any citizen to file a verified complaint upon endorsement by a House member.

These aren’t optional niceties; they’re mandates with timelines—include in the Order of Business within ten session days, refer to the Justice Committee within three.

Adiong waves the rules requiring the Secretary General’s receipt to “determine completeness” and trigger referral to the Speaker. But does this bureaucratic gatekeeping bow to the Constitution, or vice versa? Spoiler: The Constitution reigns supreme, as the Supreme Court hammered in Francisco v. House of Representatives (G.R. No. 160261, 2003), where it invalidated House maneuvers that flouted due process and the one-year bar under Section 3(5). There, the Court defined “initiation” as filing and referral, stressing that procedural games can’t nullify constitutional intent.

Here’s the real sleight of hand: By refusing receipt, the House dodges triggering the one-year bar, which prohibits multiple proceedings against the same official in a year. This isn’t “procedural purity”; it’s manipulation, ensuring no clock starts on Marcos’ accountability for alleged graft. And what of a rule creating a single point of failure? If the Secretary General’s absence—recess or not—halts filings, it effectively nullifies citizens’ rights. That’s not just unconstitutional; it’s a mockery of Gutierrez v. House of Representatives Committee on Justice (G.R. No. 193459, 2011), where the Court upheld discretion but demanded fairness and reasonableness. Question: Can a rulebook sideline the supreme law? The answer, per the Constitution’s primacy, is a resounding no.

The Political Menagerie: Shields, Junk, and Dynastic Warfare

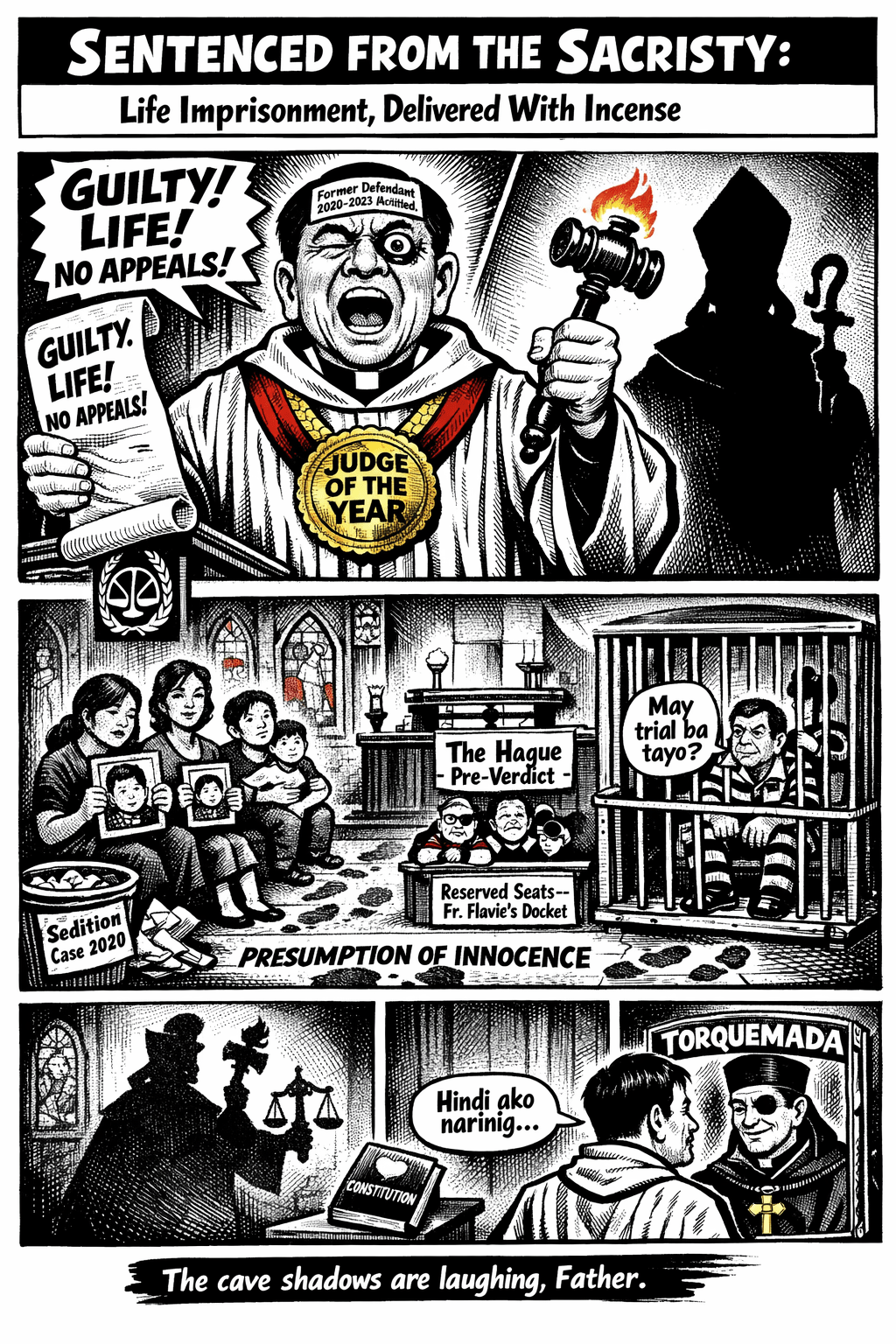

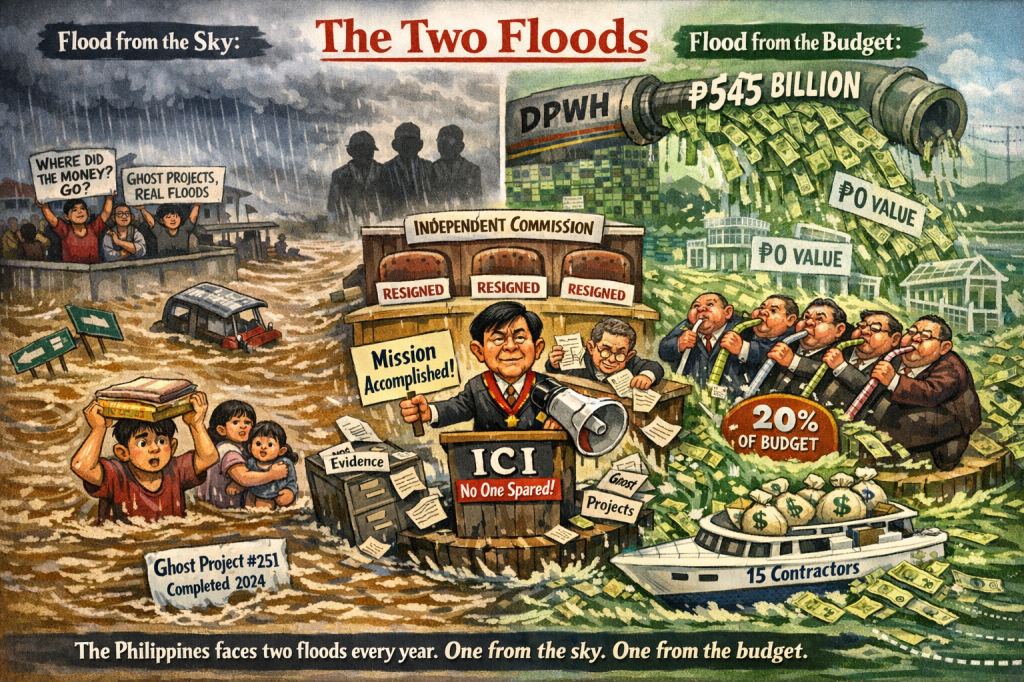

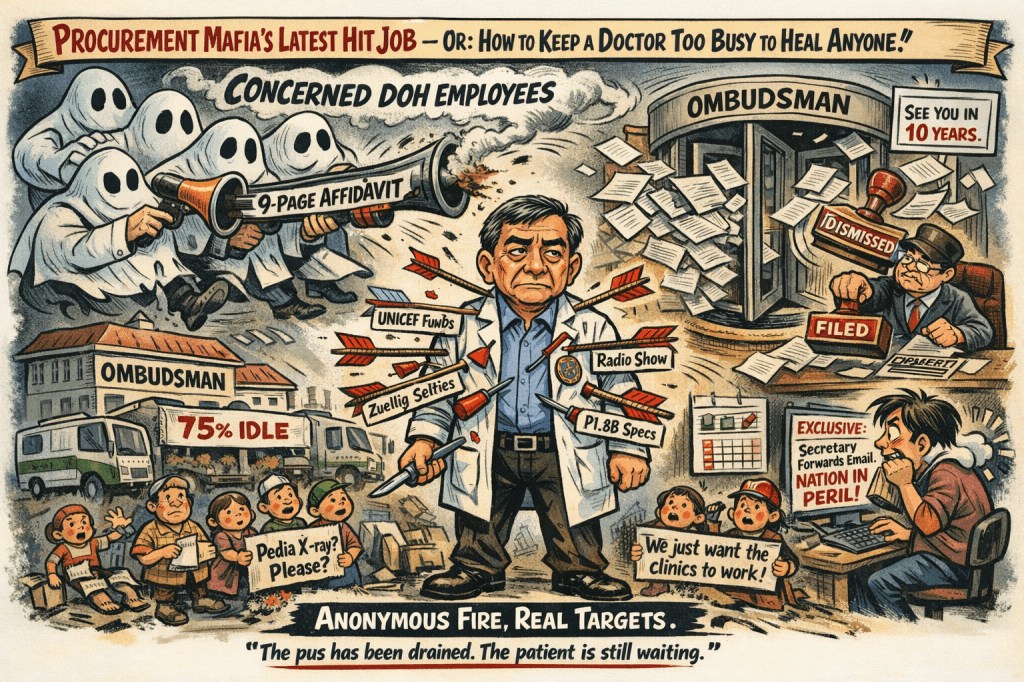

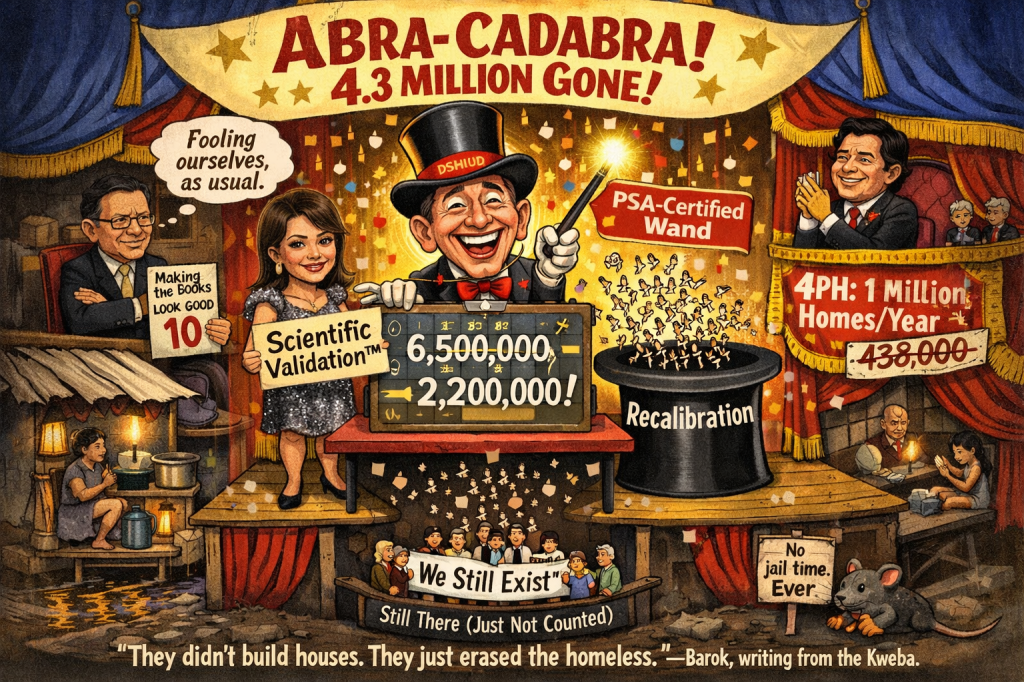

Peel back the procedural veneer, and the motivations slither into view like snakes in a pit. Adiong and House leadership, Marcos loyalists to the core, frame this as “integrity protection.” Please. It’s transparent shielding for the President, whose flood control fund debacle reeks of corruption—PHP 545 billion siphoned via insertions to allies, fake coordinates, and recanting witnesses.

This non-receipt isn’t about rules; it’s inoculation against scrutiny, especially as the Marcos-Duterte civil war rages.

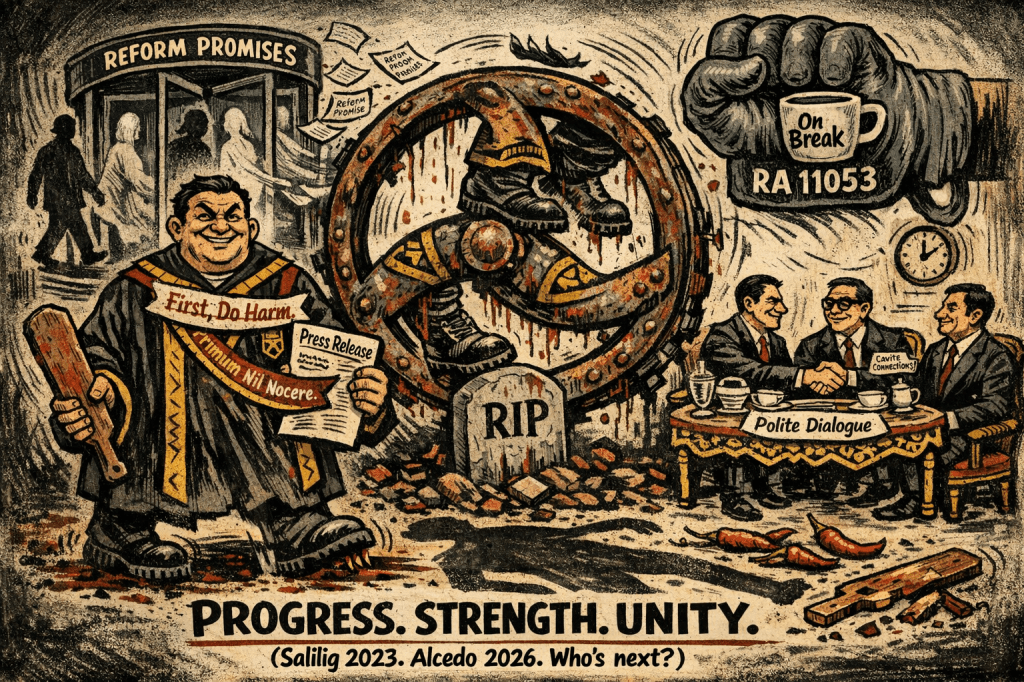

The complainants? A motley crew. The opposition Makabayan bloc pushes genuine accountability for betrayal of public trust, tying into the Senate’s probe on misused funds. But pro-Duterte factions? Rumors swirl that their “junk” complaints are staged—weak filings meant to trigger the one-year bar and block stronger ones, a tactic echoing the quashed Sara Duterte impeachment in 2025. It’s poetic: Dutertes retaliating for Sara’s ouster, amid looming ICC probes on the drug war. Fugitive ex-Rep. Zaldy Co dangles testimony from abroad, but only if it suits the intrigue.

This procedural skirmish is but a battle in the ugly dynastic feud, where Marcos consolidates via budget control, and Dutertes plot revenge. Adiong’s “no refusal” claim? It’s refusal by another name, cloaked in recess excuses.

Pathways to Prosecution: From Dereliction to Mandamus

Critique alone won’t suffice; let’s map the accountability traps. Garafil and Adiong’s refusal could smack of dereliction, violating Republic Act No. 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act), Section 3(e), by giving Marcos unwarranted benefits through delay—undue injury to the public trust. Under Republic Act No. 6713 (Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees), their “ethical standards” ring hollow when absence halts constitutional duties. The Ombudsman should probe for grave misconduct under Republic Act No. 6770 (Ombudsman Act), potentially leading to Sandiganbayan charges.

For the House, the Ethics Committee—however toothless under Marcos’ majority—could scrutinize Adiong’s partisanship. Complainants: Refile, but better yet, petition the Supreme Court for mandamus to compel receipt, invoking Article VIII, Section 5(1) to enforce constitutional mandates. Witnesses like recanters face perjury under the Revised Penal Code; filers of frivolous complaints risk disbarment.

And Marcos? If the flood scandal holds—kickbacks, fake projects—impeachment is the gateway, followed by plunder charges under Republic Act No. 7080 (Plunder Law).

The Rallying Cry: No More Technicalities Over Truth

Enough with the procedural fog; it’s time to burn it away. Demand transparency: Release Garafil’s travel authority and the House’s “contingency plans” for absences—prove this wasn’t orchestrated evasion. Demand accountability for the flood control billions looted while Filipinos drown in neglect. And demand judicial thunder: Supreme Court, affirm that the Constitution trumps any rulebook ruse, as in Francisco and beyond.

The Rule of Law must prevail over the rule of technicalities, or we’ll all be left holding the receipt for a broken democracy. Wake up, Philippines—before the next “out-of-office” reply sells out the nation.

Key Citations

A. Legal & Official Sources

- Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. Republic Act No. 3019, The Lawphil Project.

- Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees. Republic Act No. 6713, The Lawphil Project, 20 Feb. 1989.

- The Ombudsman Act of 1989. Republic Act No. 6770, The Lawphil Project, 17 Nov. 1989.

- An Act Defining and Penalizing the Crime of Plunder. Republic Act No. 7080, The Lawphil Project, 12 July 1991.

- The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines – Article XI. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines.

- Francisco, Ernesto B., Jr. v. House of Representatives. G.R. No. 160261, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 10 Nov. 2003, LawPhil Project.

- Gutierrez, Ma. Merceditas N. v. House of Representatives Committee on Justice. G.R. No. 193459, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 15 Feb. 2011, LawPhil Project.

B. News Reports

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment