From Paper Dikes to Real Yachts: The Secretary’s Masterclass in Liquid Assets

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — January 27, 2025

BEHOLD, the Senate Blue Ribbon Committee hearing on January 19, 2026: a stage set for the absurd, where former Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) Secretary Manuel Bonoan jetted back from his suspiciously extended American holiday—not out of patriotic duty, mind you, but to dodge a contempt citation that might cramp his style. There he sat, the reluctant star of this latest episode in Philippine anti-corruption kabuki, facing senators whose outrage was as scripted as a teleserye plot twist.

Bonoan, with the poise of a man who’s memorized his lines, denied everything without even glancing at the affidavit accusing him of pocketing P2.25 billion in kickbacks. Senators like Win Gatchalian played the stern inquisitors, tossing barbs like “How can a secretary let all of this happen?” while the gallery murmured. But let’s call it what it is: not a quest for justice, but a ritual dance where the powerful pirouette around accountability, leaving the taxpayer soaked in the deluge.

And so we arrive at the mocking heart of it: Negligence or corruption? Why not both, served with a side of systemic impunity that lets the floodwaters of graft rise unchecked?

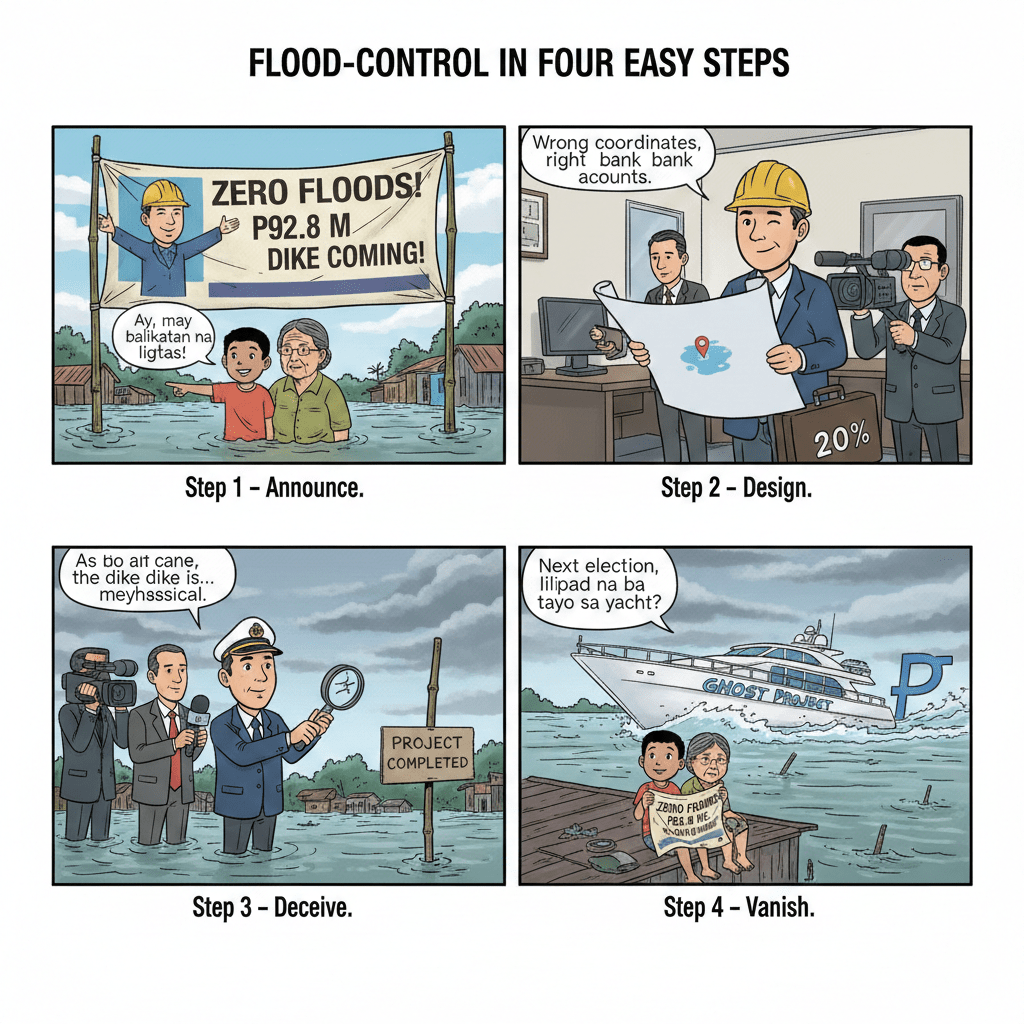

The Anatomy of a Heist: “Ghost Projects” and Very Real Money

Let’s carve into the cadaver’s core, shall we? The so-called flood control scam isn’t some petty pickpocketing; it’s a grand larceny orchestrated under the guise of public service.

Picture this: a P92.8-million dike in Pandi, Bulacan, that’s as real as a politician’s promise—existing only on falsified blueprints and, presumably, in the swollen bank accounts of the schemers. This isn’t mere oversight; it’s a metaphysical farce where corruption warps geography itself, with Bonoan allegedly submitting “wrong coordinates” to Malacañang, turning real floods into phantom fixes.

Ping Lacson called it a deliberate deception to “divert and discredit” the probe, but why stop there? It’s corruption so brazen it gaslights gravity, letting rivers rage while funds vanish into ethereal voids.

Zoom out to the kickback ecosystem: it starts with congressional insertions—the poisoned seeds planted by lawmakers hungry for their cut. DPWH, under Bonoan, cultivates them through rigged bids and approvals, harvesting 20-30% commissions for all involved.

Whistleblowers like Roberto Bernardo and Henry Alcantara lay it bare: Bonoan allegedly facilitated these for P2.25 billion personally, with 15 contractors cornering P100 billion in projects via bribes and fraud. Bernardo’s affidavit paints Bonoan as the maestro, while Alcantara, turning state witness, coughed up P181 million in ill-gotten gains as a down payment on truth.

And the implicated? Names like Bong Revilla (already tangled in his own Bulacan graft mess) and Zaldy Co swirl in the muck, alongside hints of other lawmakers and officials. This isn’t a scam; it’s a syndicate, where ghost projects in Bulacan and Davao Oriental aren’t anomalies but the business model, turning taxpayer pesos into private yachts while the poor wade through waist-deep water.

The Prosecution Obstacle Course: Where Evidence Goes to Die and Impunity Wins Gold

Yikes, the Philippine legal framework—a fearsome arsenal on paper, a rusty blunderbuss in practice. Start with Republic Act No. 3019, the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act: Section 3(e) skewers those causing undue injury through “manifest partiality, evident bad faith, or gross inexcusable negligence,” perfect for Bonoan’s alleged kickback facilitation and ghost project approvals.

Then there’s Republic Act No. 7080, the Plunder Law, demanding life imprisonment and forfeiture for amassing over P50 million through corruption—Bonoan’s purported P2.25 billion sails right past that threshold like a superyacht through a storm drain.

And don’t forget the Revised Penal Code‘s Articles 210-212 on bribery and Article 217 on malversation, ready to nail solicitation and fund diversion. In theory, these promise perpetual disqualification, hefty fines, and decades behind bars. In reality? They’re enforced with the vigor of a Commission on Audit (COA) audit during siesta: delays, acquittals, and slaps on the wrist that sting less than a mosquito bite.

Prosecution pathways? A roadmap paved with good intentions and riddled with bad-faith potholes. The Ombudsman kicks off with investigations under Republic Act No. 6770, potentially leading to preventive suspension and charges.

From there, the Department of Justice (DOJ) files complaints, granting witness protection to turncoats like Bernardo and Alcantara, before the Sandiganbayan takes over for trial—exclusive jurisdiction for graft cases, where penalties bite hard if they ever land.

But here’s the cynicism: “lack of direct evidence” becomes the getaway car, with Bonoan already dismissing Bernardo as a “liar.” Attack whistleblower credibility, invoke the “presumption of regularity” for those absurdly vetted budgets, and fall back on “I was just delegating” to subordinates like the late Maria Catalina Cabral. Political weaponization adds another layer of sludge, turning probes into partisan theater.

And then there’s Republic Act No. 1379, the Forfeiture Law—a fantasy sword in a decorative scabbard. This gem declares any public officer’s property “manifestly out of proportion” to their salary (say, Bonoan’s modest P200,000 monthly vs. P2.25 billion) as prima facie ill-gotten, shifting the burden to prove legitimacy.

It’s civil, independent of criminal charges, and can snatch assets even if registered to relatives—echoing the Supreme Court’s Republic v. Marcos (G.R. No. 130371, 2003), where ill-gotten wealth was forfeited despite clever hiding. Perfect for Bonoan, right? Yet it’s underused, gathering dust while the powerful laugh.

Will the Solicitor General file a forfeiture case, tracing those funds via Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) probes under the Anti-Financial Account Scamming Act? Or is Republic Act No. 1379 just another relic, like the ethics in Philippine politics?

The Defense Playbook: A Critique of the Expected Alibis

Bonoan’s denials are as predictable as monsoon rains. First, the “single witness” gambit: trash Bernardo and Alcantara as liars, ignoring how Alcantara’s P181 million repayment and the pattern of anomalies—recurrent ghost projects across provinces—corroborate the tale like a forensic fingerprint. Chain of custody? Good luck; the returned funds and COA flags shred that veil.

Then, “command ignorance”: Bonoan claims he didn’t know, relying on subordinates in a department infamous for graft since the Spanish era. Poppycock. In a century-old cesspool like DPWH, not knowing is either criminal negligence under Republic Act No. 3019 Sec. 3(e) or a lie so bald it shines.

Gatchalian nailed it: “How can a secretary let all of this happen?” Three years in charge, and anomalies multiply? That’s not delegation; that’s dereliction, amplified by his failure to wield the anti-graft committee he created as anything but a fig leaf.

Finally, the “systemic failure, not personal fraud” dodge: concede the rot, blame the institution. But this makes Bonoan more culpable—he didn’t just inherit the mess; he allegedly monetized it, perfecting insertions for personal gain. As Estrada v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. No. 148560, 2001) shows, a series of acts like these recurrent scams equals plunder, not accident.

The Rotten Ecosystem: Eviscerating the DPWH and Institutionalized Corruption

This isn’t Bonoan’s solo act; it’s the DPWH symphony of sleaze, with him as conductor. Trace the lineage: from Mark Villar’s era of overpriced anomalies to Cabral’s ghostly legacies, now Bonoan’s multibillion encore.

DPWH isn’t plagued by corruption; it’s a corruption machine with a public works facade, where P1 trillion in flood funds since 2011 evaporate while floods claim lives. The “internal anti-graft committees”? Self-parody, like foxes guarding the henhouse.

Link it to the human toll: stolen billions mean unrepaired dikes, drowned communities, a nation perpetually underwater—literally and figuratively.

This is the national malaise: not anomaly, but archetype. Congressional insertions feed the pigs, contractors harvest the slop, officials wallow in it. It’s a pirate kingdom masquerading as a republic, where trust erodes like riverbanks, taxes waste like spilled sewage, and insecurity festers in the floodplains of impunity.

Demands, Reforms & A Mocking Dose of Reality

Enough dissection; time for demands. Ombudsman and DOJ: move with uncharacteristic speed—file plunder under Republic Act No. 7080, graft under Republic Act No. 3019, and especially forfeiture under Republic Act No. 1379 now, before Bonoan’s assets flee like he allegedly did to the US.

Not just Bonoan, but every link: lawmakers, contractors, the whole chain. Satirize the “big fish vs. small fry” nonsense? Cast the net wide, or admit it’s all theater.

Reforms? With a sneer: Enact the “Stop Feeding the Pigs Act” to end congressional insertions. Mandate real-time GPS and drone tracking—a “YouTube for Concrete” to expose ghosts before they haunt.

Beef up Ombudsman and COA with teeth and budgets, not platitudes. Make Republic Act No. 1379 a routine weapon, not a museum piece. But reality mocks: these will gather dust like past promises, perpetuating eroded trust, wasted taxes, national insecurity.

Yet, in this betrayed republic, a stubborn hope flickers: that this scandal, dissected publicly, sparks the fury to drown the corrupt in their own deluge. Until then, the flood rises.

Watching the same movie for the nth time, still no happy ending in sight,

— Barok

Because hope is expensive and impunity is free.

Key Citations

A. Legal & Official Sources

- Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. Republic Act No. 3019, Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, 17 Aug. 1960.

- Act No. 3815: An Act Revising the Penal Code and Other Penal Laws. 8 Dec. 1930. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines.

- An Act Defining and Penalizing the Crime of Plunder. Republic Act No. 7080, Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, 12 Jul. 1991.

- Republic Act No. 1379: An Act Declaring Forfeiture in Favor of the State Any Property Found to Have Been Unlawfully Acquired by Any Public Officer or Employee and Providing for the Proceedings Therefor. 18 June 1955. LawPhil Project.

- The Ombudsman Act of 1989. Republic Act No. 6770, Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, 17 Nov. 1989.

- Republic v. Marcos. G.R. No. 130371, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 4 Aug. 2009, LawPhil Project.

- Estrada v. Sandiganbayan. G.R. No. 148560, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 19 Nov. 2001.

B. News Reports

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment