Plunderers Welcome… Provided They Bring a Billion-Dollar “Sorry We Stole It” Gift Receipt

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — January 28, 2026

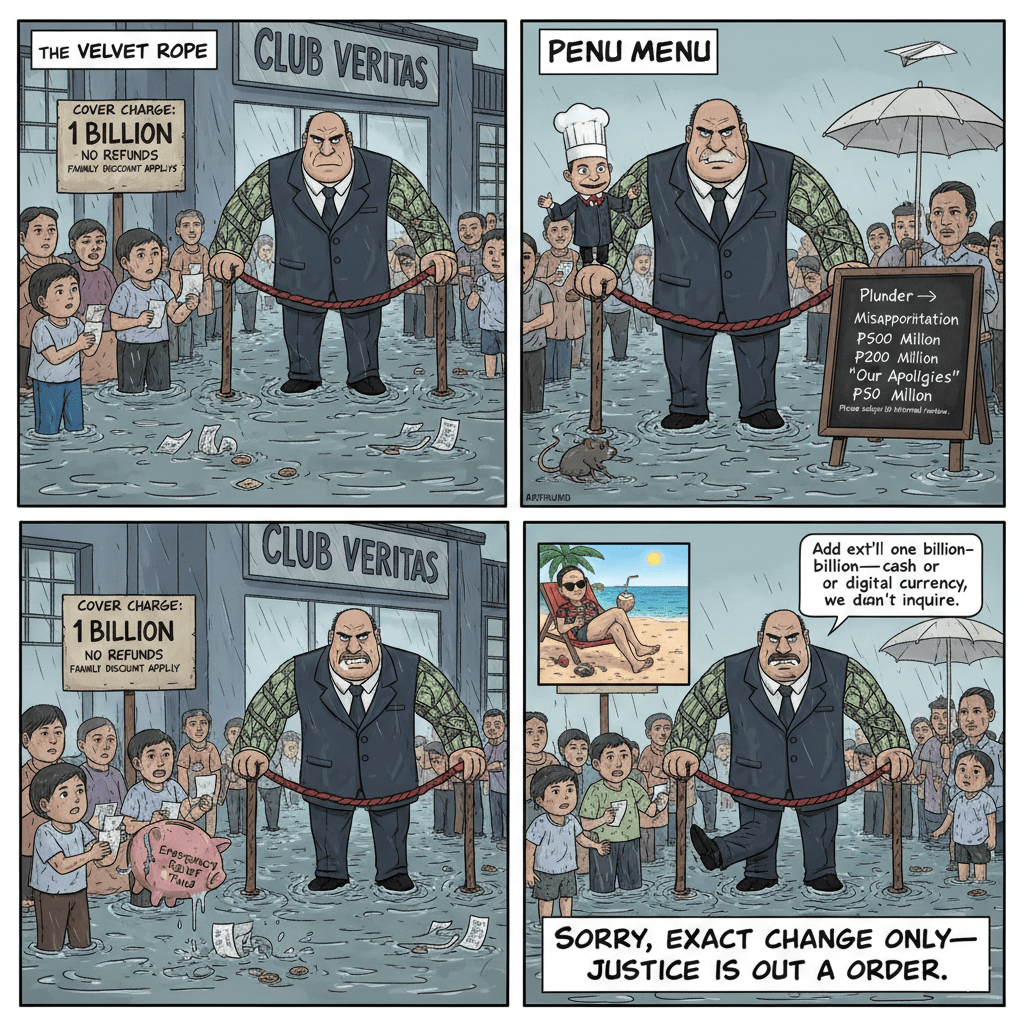

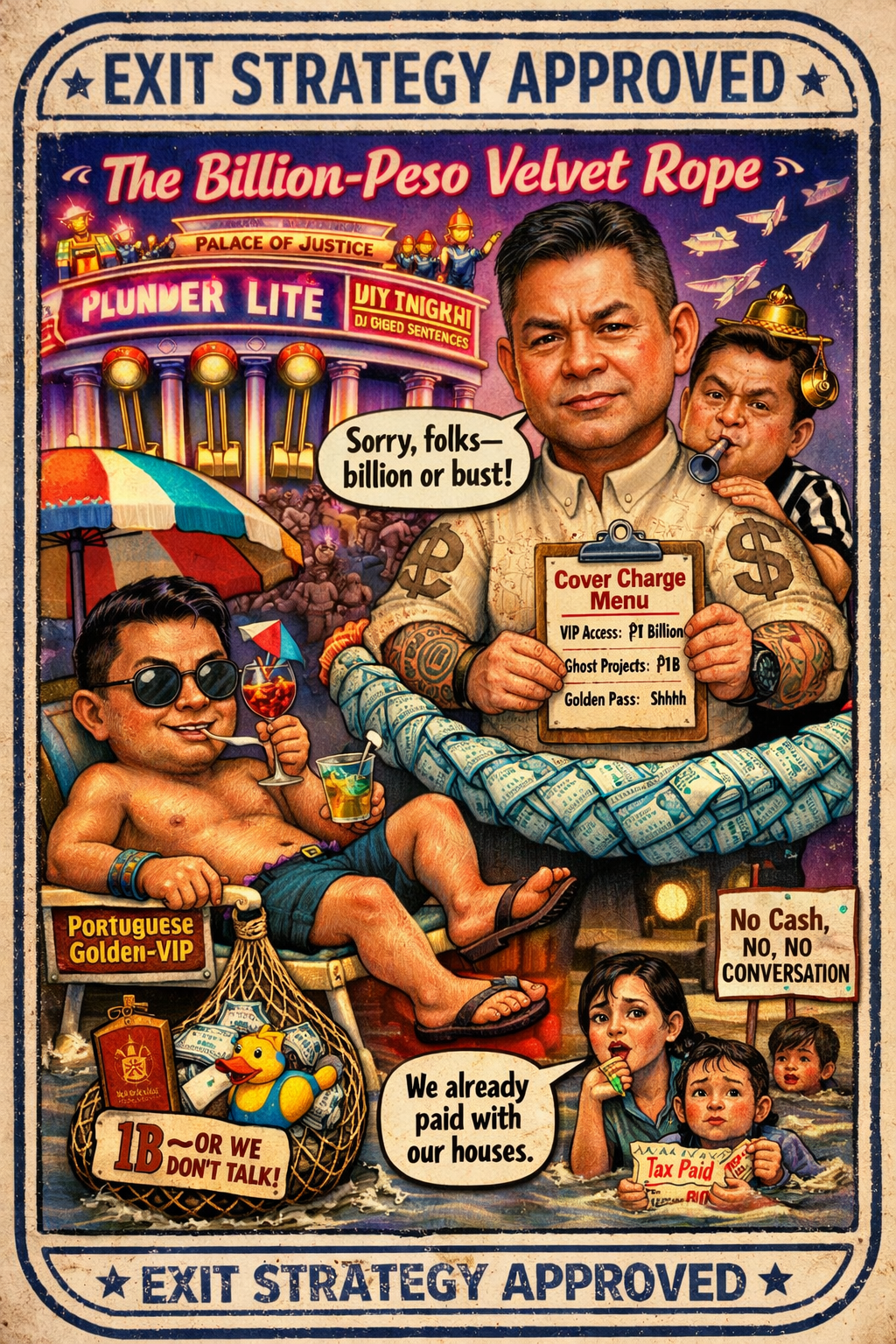

BEHOLD, Manila, the city that never sleeps—because someone is always counting someone else’s money. On January 27, 2026, Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) Secretary Jonvic Remulla delivered what may be the most refreshingly honest moment in Philippine politics since the last time someone admitted the system runs on cash. To fugitive former Congressman Zaldy Co, currently enjoying the Portuguese sunshine on a golden visa: return $1 billion (or roughly ₱59 billion of the people’s money) before “we can talk.” This demand was laid out in a public statement reported by ABS-CBN News.

Not “before we prosecute you.” Not “before we extradite you.” Before we even deign to have a conversation. This is not accountability; this is a cover charge for entry into the plea-bargain lounge.

The Remulla Family Discount: When the Ombudsman’s Brother Sets the Menu Price

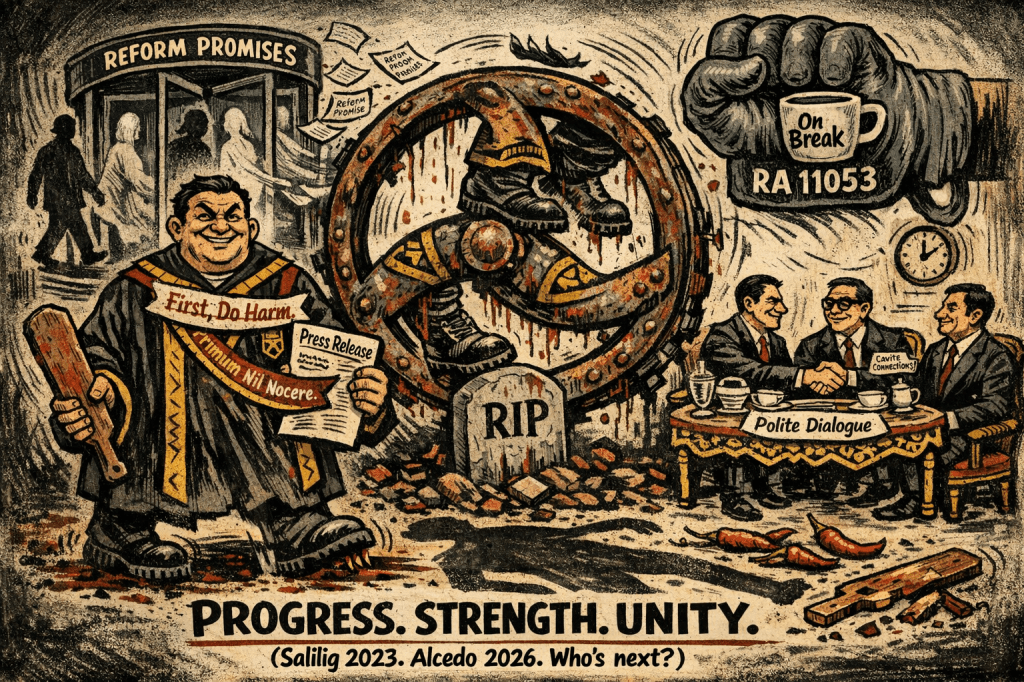

Let us savor the exquisite conflict of interest here. Jonvic Remulla, head of the DILG, publicly dictates the opening bid for negotiations in a case being prosecuted by… his brother, Ombudsman Jesus Crispin “Boying” Remulla. The Ombudsman Act (Republic Act No. 6770) grants the Ombudsman primary jurisdiction and independence precisely to insulate the office from executive arm-twisting. Yet here we have the DILG chief playing price-checker on the family business.

Remulla is careful to say the final decision rests with the Ombudsman. Of course it does. But when your brother broadcasts the acceptable ransom on national television, is that guidance or gentle fraternal persuasion? In any other jurisdiction this would trigger recusal motions and ethics complaints. Here it’s just Tuesday.

Zaldy Co: The Impudent Oligarch on Permanent Vacation

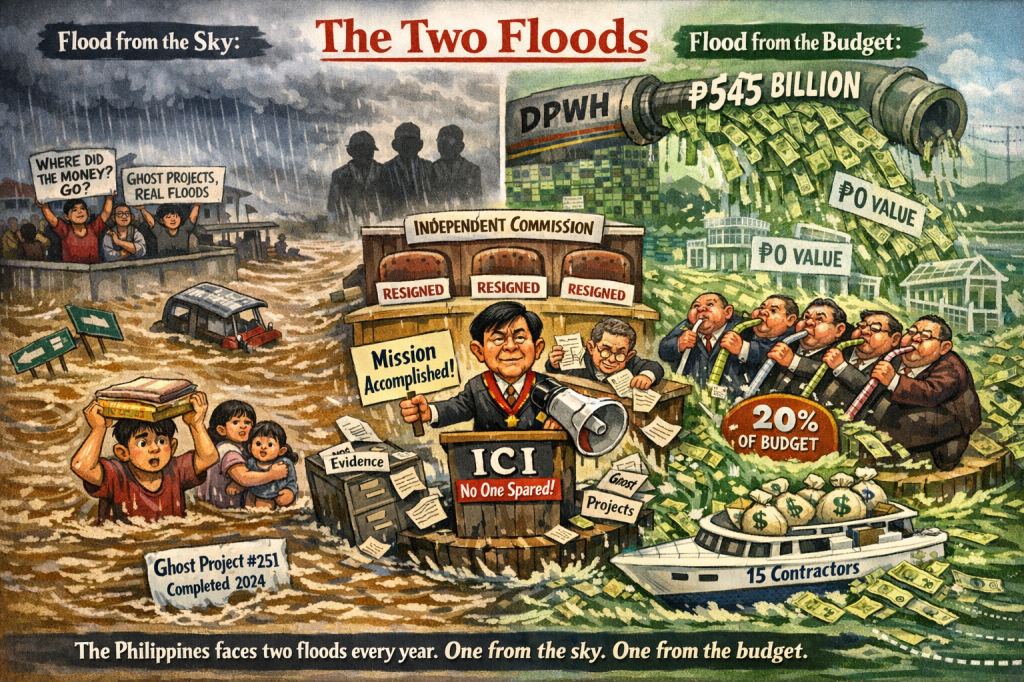

Zaldy Co—former chair of the House appropriations committee, architect of countless budget insertions (the polite term for congressional pork)—now stands accused of turning flood-control funds into personal slush. The poster child case: a P289-million road dike along the Mag-Asawang Tubig River in Naujan, Oriental Mindoro, built with substandard materials that allegedly cost the government P63.9 million in damages.

Co denies everything, of course. He has issued video statements from exile accusing everyone from the President downward of political persecution. Meanwhile, he holds a Portuguese passport and golden visa, having reportedly planned his exit strategy a decade ago. Extradition? No treaty with Portugal. Interpol Red Notice? Nice souvenir, but Portugal isn’t obligated to hand him over. So Co lounges in Lisbon while the Sandiganbayan issues warrants that might as well be paper airplanes.

The man allegedly pocketed kickbacks from ghost projects and substandard dikes, then fled. Now he sends “feelers” through priests, apparently hoping to negotiate from the comfort of a villa. Victimhood is the final luxury of the caught crook.

$1 Billion: Where Did That Number Come From, Anyway?

Remulla throws around $1 billion like it’s the exact change from a jeepney fare. Is this a forensic accountant’s figure? A back-of-the-envelope tally of all alleged insertions across multiple projects? Or simply the headline-grabbing number that makes the administration look tough? The Ombudsman’s complaints cite violations of the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act (Republic Act No. 3019), the Anti-Plunder Act (Republic Act No. 7080), and Article 217 of the Revised Penal Code (Malversation)—serious enough for non-bailable detention if evidence of guilt is strong. Yet Remulla frames the whole affair as a simple refund: “Kasi in the end, pera naman ang kinuha niya. Kung sinoli niya ‘yung pera, wala naman siyang pinatay.”

Translation: You didn’t kill anyone, so pay the cover charge and we’ll downgrade the charges. Welcome to Plunder Lite.

Plea Bargain or Plunderer’s Subscription Service?

Rule 116 of the Rules of Court allows plea bargaining with the prosecutor’s consent. Restitution can mitigate penalties. The Supreme Court even upheld a similar arrangement in the Carlos Garcia case—where a general returned millions and walked with a lighter sentence, sparking nationwide outrage.

But when the brother of the chief prosecutor publicly sets the price tag, the arrangement starts smelling less like justice and more like a pay-to-play downgrade menu: Plunder to graft, graft to simple malversation, malversation to “sorry po.” The Garcia precedent already taught us that restitution-first deals are legally possible but politically radioactive. They fuel the perception that justice is for sale to anyone with enough offshore accounts.

The Real Scandal: Budget Insertions as National Sport

This isn’t about one congressman or one project. It’s about the entire ecosystem. Powerful House members insert billions into the budget for “flood control” and “infrastructure.” Contractors kick back percentages. Projects turn into ghost dikes or substandard concrete ribbons. Floods come, people drown, and the money is long gone. Then the fugitive flees, the government begs for a refund, and the cycle restarts.

Congress needs to investigate itself—not just Co, but the entire mechanism of budget insertions that keeps patronage alive. The Commission on Audit, the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), the Anti-Money Laundering Council (AMLC)—all must release the full paper trail. Transparency isn’t optional; it’s the only antidote to this institutionalized looting.

Due Process, Independence, and the People Who Actually Got Flooded

True justice demands the Ombudsman act free from fraternal soundbites. Prosecutorial independence is not a slogan; it’s a constitutional firewall. Any plea bargain must be transparent, judicially supervised, and require Co to name bigger fish—if there are any left un-named.

Meanwhile, in Oriental Mindoro and flood-ravaged communities nationwide, families still wade through knee-deep water while the alleged architects sip espresso abroad. The real demand isn’t $1 billion in restitution. It’s governance that builds dikes that don’t collapse, budgets that don’t disappear, and leaders who serve people instead of treating public funds like personal ATMs.

Forecast: The Likely Farcical Ending

Co will probably stay in Portugal, dribbling out occasional videos. The government will issue more notices, freeze a few accounts, and declare victory when they recover a fraction of the alleged loot. The Remulla brothers will continue to play good cop/tough cop. And the public will sigh, because this is just another episode in the long-running telenovela called Philippine Anti-Corruption Theater.

Until Congress dismantles the pork machine, until the Ombudsman can prosecute without family commentary, until fugitives can’t buy golden visas while their victims buy rubber boats—nothing changes.

But hey, at least the cover charge is only a billion dollars.

Still waiting for the day the billionaires pay before the poor do,

— Barok

Key Citations

A. Legal & Official Sources

- Republic Act No. 6770. The Ombudsman Act of 1989. Congress of the Philippines, 17 Nov. 1989, LawPhil Project.

- Republic Act No. 3019. Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. Congress of the Philippines, 17 Aug. 1960, LawPhil Project.

- Republic Act No. 7080. An Act Defining and Penalizing the Crime of Plunder. Congress of the Philippines, 12 July 1991, LawPhil Project.

- Act No. 3815. Revised Penal Code. Philippine Legislature, 8 Dec. 1930, LawPhil Project.

- Rules of Court. Supreme Court of the Philippines, LawPhil Project.

Leave a comment