From Transcendental Courage to Procedural Paralysis: The Slow Death of Judicial Spine

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — February 5, 2026

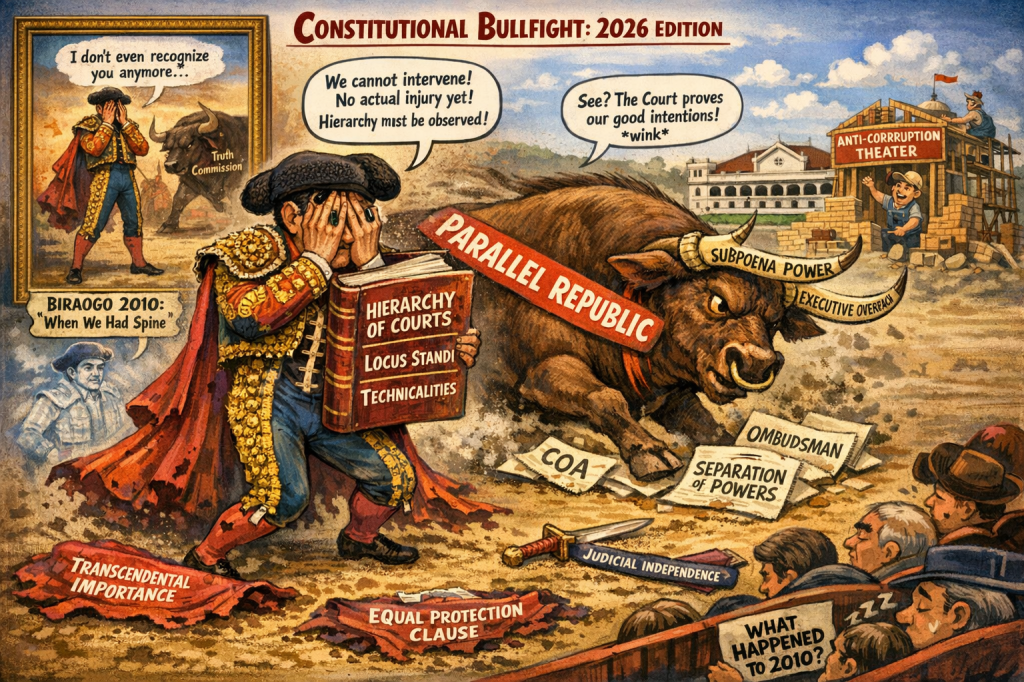

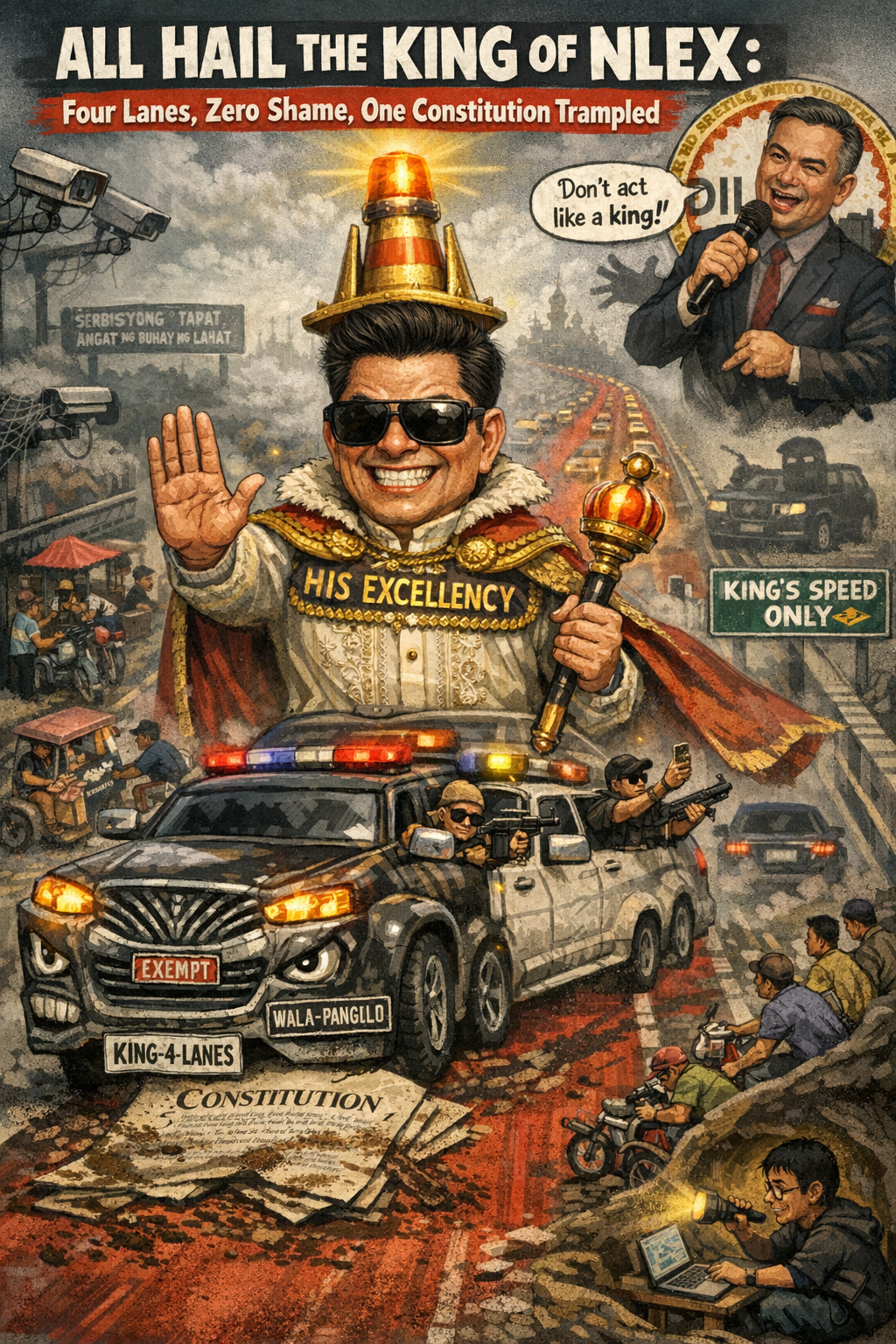

DEAR esteemed magistrates of the Supreme Court (SC): congratulations. Yesterday, February 4, 2026, you managed to dodge a constitutional bullet with the grace of a matador who simply steps aside and lets the bull charge into the wall. In dismissing the petition against Executive Order (EO) No. 94—the one that birthed the Independent Commission for Infrastructure (ICI)—you wrapped yourselves in the comforting cloak of “procedural requirements,” all while the executive branch quietly constructs a parallel anti-corruption empire answerable to no one but Malacañang.

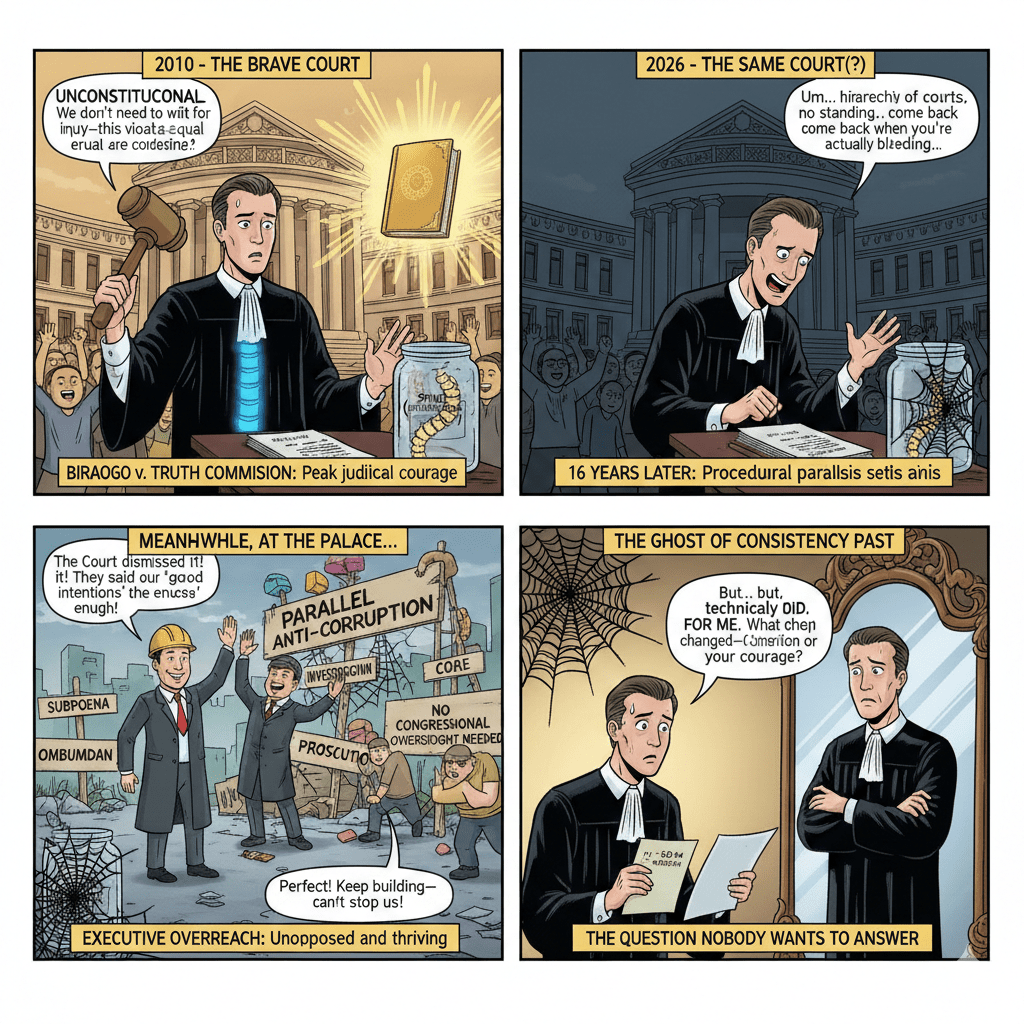

Back in 2010, when I had the honor of leading the charge in Biraogo v. Philippine Truth Commission, this very Court threw open its doors, relaxed every technicality in the book, and courageously struck down an unconstitutional monstrosity. Today? You slammed those doors shut, locked them, and swallowed the key. What a difference sixteen years makes—or perhaps what a difference the occupant of Malacañang makes.

The Procedural Farce: A Tired Bureaucratic Shield

Let us dissect the Court’s stated reasons for dismissal, shall we? They are, after all, the flimsy fig leaves covering judicial timidity.

First, the ever-reliable hierarchy of courts doctrine. The SC scolded the petitioners—Jacinto Paras and company—for daring to file directly with the Highest Tribunal without first trudging through the Regional Trial Courts. “Direct recourse is allowed only in exceptional cases,” the Court intoned, “and petitioners failed to cite any compelling reason to bypass lower courts.”

Oh, please. This is the same Court that, in Biraogo, Araullo v. Aquino, and Belgica v. Ochoa, happily entertained direct petitions when the issues involved transcendental questions of executive overreach and the misuse of public funds. When the President creates an entirely new investigatory body with subpoena powers, funded by contingent funds, and tasked with probing a decade’s worth of infrastructure anomalies—while conveniently overlapping with constitutional watchdogs—is that not exceptional? Is that not transcendental? Or does “transcendental importance” now expire like a parking meter when the political winds shift?

Second, the lack of actual case or controversy. The SC insisted that petitioners showed no personal injury, no direct adverse effect on their rights. Must we wait, Your Honors, for the ICI to actually subpoena someone, raid an office, or recommend a prosecution before we are allowed to ask whether the President may constitutionally create such a creature in the first place? Must the roof collapse entirely before the Court deigns to inspect whether the beams are rotten?

This is not prudence; this is procrastination dressed as principle. In Biraogo, the Court did not wait for the Truth Commission to issue its first subpoena. It saw the facial constitutional defect—an arbitrary, discriminatory mandate—and struck it down before the damage was done. Here, the Court demands a corpse on the table before it will perform the autopsy.

The Substantive Void: Questions Too Dangerous to Touch

By hiding behind procedure, the SC deliberately ignored the profound constitutional questions screaming from EO 94.

Equal Protection

The petitioners argued—correctly—that the ICI may arbitrarily single out certain projects, eras, or political adversaries while sparing others. In Biraogo, this Court thundered that an investigatory body cannot create a “class of one” without rational basis. The Truth Commission’s fatal sin was limiting its gaze to the Arroyo administration. The ICI’s mandate covers “the past decade” of flood control projects—conveniently encompassing the Duterte years while perhaps sparing others. Is that not the same arbitrary classification dressed in broader language? The Court fled from the question rather than apply its own precedent under the Equal Protection Clause (Article III, Section 1 of the 1987 Constitution).

Separation of Powers

Only Congress may create public offices and appropriate funds. The President may reorganize existing agencies, but Biraogo made clear that executive power does not extend to inventing entirely new bodies with quasi-prosecutorial and investigative powers (see also Article VI and Article VII of the 1987 Constitution). The ICI is not a mere fact-finding committee; it can subpoena witnesses, take testimony under oath, and recommend charges to the Department of Justice. That smells suspiciously like legislation by another name. Yet the Court refused to sniff the air.

Encroachment on Constitutional Watchdogs

The Office of the Ombudsman (Article XI of the 1987 Constitution) and the Commission on Audit (COA) (Article IX-D of the 1987 Constitution) are constitutionally armored for a reason: independence from political pressure. The ICI duplicates their functions, potentially dilutes their authority, and answers ultimately to the President who appointed its members. This is not cooperation; this is a silent coup against independent oversight. The Court, guardian of the Constitution’s architecture, looked away.

Motive and Theater

And let us not ignore the Palace’s gleeful response. Undersecretary Claire Castro crowed that the dismissal “showed the people the President’s good intention” to investigate anomalous projects. Good intentions? Since when does subjective benevolence immunize an act from constitutional scrutiny? The Court in Biraogo did not inquire into President Aquino’s heart; it examined the text and effect of the order. Here, the Court effectively endorsed the Palace line: if the President says it’s for anti-corruption, we must avert our eyes.

The Biraogo Blueprint Betrayed

This is the core betrayal. In 2010, this Court—faced with an executive order creating an investigatory body—relaxed locus standi, waived hierarchy objections, invoked transcendental importance, and reached the merits. It established a doctrine: when the executive experiments with the republic’s accountability architecture, the Court will not wait for blood in the water.

In 2026, the same Court—faced with an eerily similar executive order—revived every procedural barrier, refused to invoke transcendental importance, and dismissed the case without touching the substance. This is not doctrinal consistency; this is passive-aggressive repeal of Biraogo. By hiding behind technicalities, the Court has effectively sanctioned unlimited executive creation of parallel investigatory bodies, rendering Biraogo a dead letter.

Impacts and Consequences: A Perilous Gray Zone

The fallout is already visible:

- Legally: Future Presidents now know they can bypass Congress with ad-hoc commissions, secure in the knowledge that the SC will demand a concrete injury before intervening. The separation of powers tilts further toward the executive.

- Politically: The Palace is emboldened; the Court appears either weak or complicit. Public perception of judicial independence erodes further.

- Public Trust: Citizens see an anti-corruption body that operates in a constitutional shadow, with resignations, opaque hearings, and persistent questions about its true targets. Faith in both the sincerity of the executive and the backbone of the judiciary crumbles.

The Demand: Resurrect Biraogo or Admit Its Death

Supreme Court, I address you directly: Article VIII, Section 1 of the 1987 Constitution vests in you the duty to settle actual controversies involving constitutional rights and to determine grave abuse of discretion. You cannot outsource that duty to “good intentions” or lower courts when the very structure of accountability is at stake.

I demand that you resurrect the spirit of Biraogo v. Philippine Truth Commission. Apply its doctrine consistently. Recognize that some constitutional questions are too urgent, too structural, too transcendent to await personal injury.

I call EO No. 94 what it is: a toothless, unconstitutional puppet show—performative anti-corruption theater that duplicates existing bodies while evading legislative oversight. Revoke it, Mr. President, or submit it to Congress for proper statutory birth.

To petitioners: refile, this time with legislators, COA officials, or Ombudsman personnel as co-petitioners to establish direct injury. Invoke transcendental importance explicitly. Frame it as a facial challenge to executive overreach.

To Congress: assert your exclusive power. Pass a genuine, statutory independent commission—or expose your own complicity in the farce.

To the public: do not accept procedural dismissals as neutrality. Demand accountability from both Palace and Court.

Because if the Supreme Court will not defend the Constitution when the executive redraws the lines of power, then who will?

The roof is already leaking, Your Honors. Pretending otherwise will not keep us dry.

Yours in perpetual disgust at judicial acrobatics and executive sleight-of-hand,

— Barok

Key Citations

A. Legal & Official Sources

- “The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines.” Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines.

- Executive Order No. 94: Creating the Independent Commission for Infrastructure. 11 Sept. 2025. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines.

- Biraogo v. Executive Secretary. G.R. Nos. 192935 & 193036, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 7 Dec. 2010, LawPhil Project.

- Araullo v. Aquino III. G.R. No. 209287, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 1 July 2014, LawPhil Project.

- Belgica v. Executive Secretary. G.R. No. 208566, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 19 Nov. 2013, LawPhil Project.

B. News Reports

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment