Floods Drown Communities While Lawyers Drown the Court in Technicalities

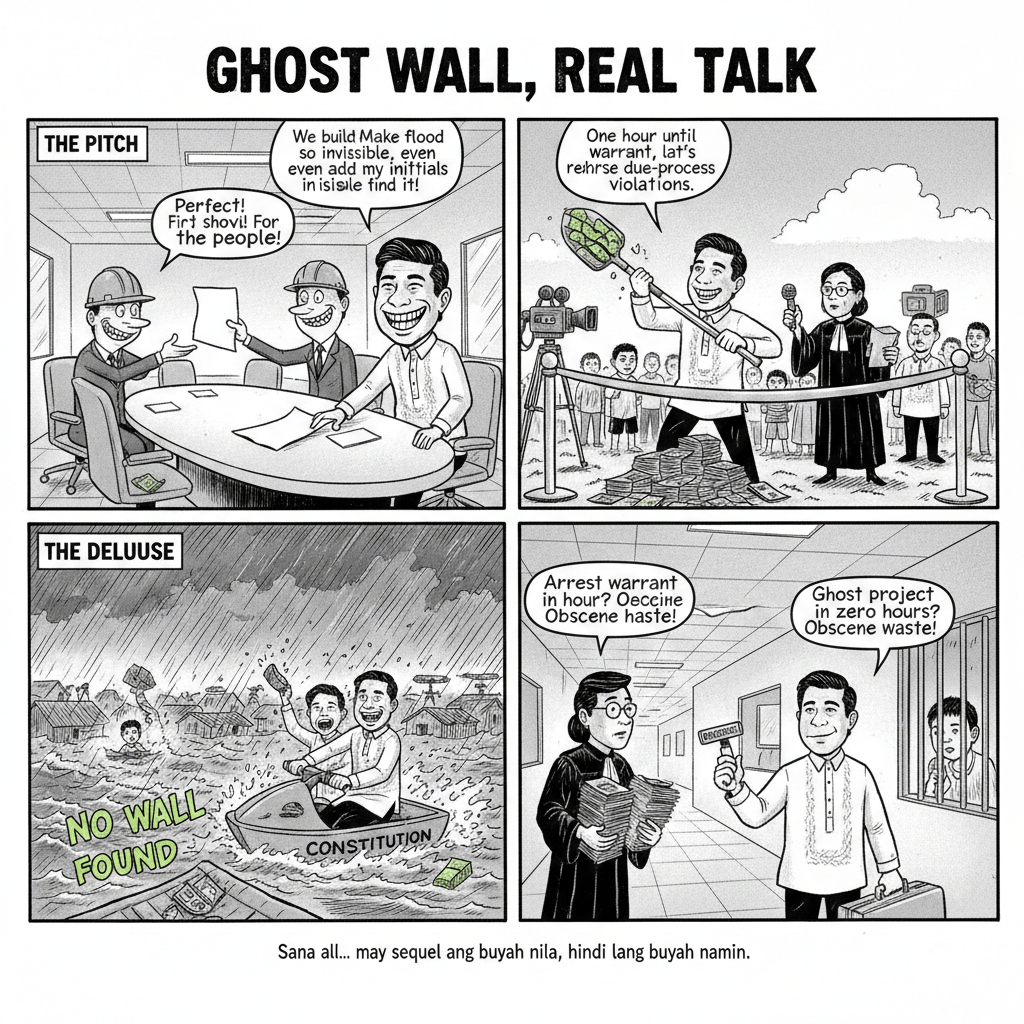

BAHOLD, the Philippine justice system—where the wheels grind with glacial indifference for the poor, yet suddenly sprout turbochargers when a big fish smells blood in the water. Former Senator Ramon “Bong” Revilla Jr. is back in detention, this time for allegedly orchestrating a P92.8-million “ghost” flood control project in Pandi, Bulacan—a structure so nonexistent it couldn’t stop a garden hose, yet somehow managed to drain public coffers with ruthless efficiency.

And who rides to the rescue? None other than Atty. Lorna Patajo-Kapunan, clutching the Constitution like a talisman and decrying “obscene haste” and “railroading,” as reported in The Manila Times.

Welcome, dear readers, to Season Three of the Revilla Legal Saga. Same plot, new props: ghost projects instead of ghost NGOs, flood control instead of pork barrel. The only constant? The Filipino taxpayer left holding the empty bucket while the elite dance their budots around accountability.

The Kapunan Gambit: Noble Defender or Master of Misdirection?

Atty. Kapunan, ever the dramatic advocate, thunders that the Office of the Ombudsman and the Sandiganbayan (the Philippines’ anti-graft court) violated Revilla’s sacred due process rights.

Her bill of particulars: an arrest warrant issued a mere hour after records reached the Third Division; no copy of the probable cause resolution furnished to the defense; Revilla served only a motion to include him as respondent instead of the full complaint-affidavit; vital documents—bidding records, contracts, audit reports—allegedly withheld. All this, she proclaims, reeks of “bending the law to suit transitory political exigencies.”

Let us pause to savor the irony, thick as lahar after Pinatubo.

While Kapunan waxes eloquent about procedural meticulousness for her client, the very scheme she defends allegedly bypassed every conceivable procedure: a flood control project declared complete without a single shovel breaking ground, funds disbursed on forged accomplishment reports, lives left vulnerable to the next typhoon because the money vanished into private pockets.

The accused, we are told, was denied an hour’s courtesy to review documents. Meanwhile, entire communities were denied actual flood mitigation—permanently, catastrophically, and with criminal intent.

Is this principled human rights advocacy? Kapunan has built a career on high-profile defenses—Janet Lim-Napoles’ illegal detention case comes to mind—and she has indeed taken pro bono stands for marginalized clients. Fair enough.

But when the client is a political dynasty scion accused of treating public funds like an ATM, the “human rights” framing lands with the subtlety of a Revilla action-movie punchline. One suspects a cocktail of genuine belief, billable-hours strategy, and political theater. After all, nothing rallies the base like crying persecution.

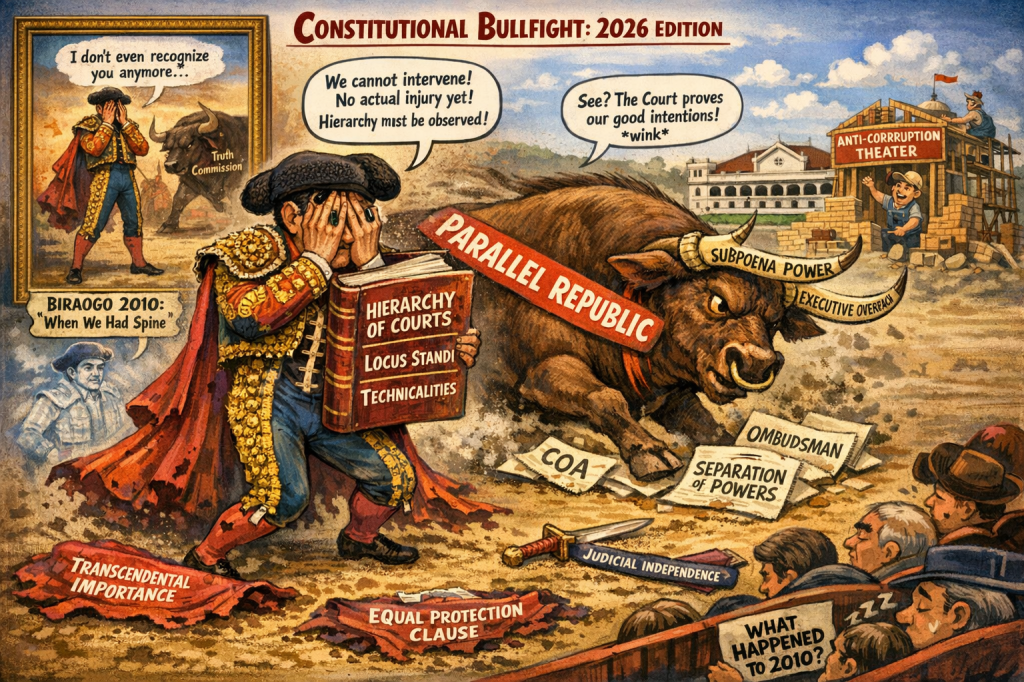

Revilla’s Legal Groundhog Day: Same Sunrise, Same Acquittal Horizon?

This is not Revilla’s first rodeo. He was acquitted in the pork barrel plunder case (2018) and graft (2021), emerging like a phoenix to resume his political career while his chief of staff rotted in prison.

Now, barely recovered from that triumph, he’s back—claiming, yet again, selective prosecution. The charges include malversation of public funds under Article 217 of the Revised Penal Code (Act No. 3815) and graft under Section 3(e) of Republic Act No. 3019. The audacity would be admirable if it weren’t so infuriating.

P92.8 million for a phantom gabion wall in Pandi. Whistleblowers—former Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) Undersecretary Roberto Bernardo and engineer Brice Hernandez—testify to cash deliveries and 25–30% kickbacks. Senate Blue Ribbon Committee draft reports (conveniently leaked, yet officially gathering dust) recommend plunder charges against Revilla and others.

And still, the narrative from Camp Revilla is victimhood. One almost expects the next campaign jingle to feature the lines: “Sa hirap at ginhawa, ako’y inaapi pa.”

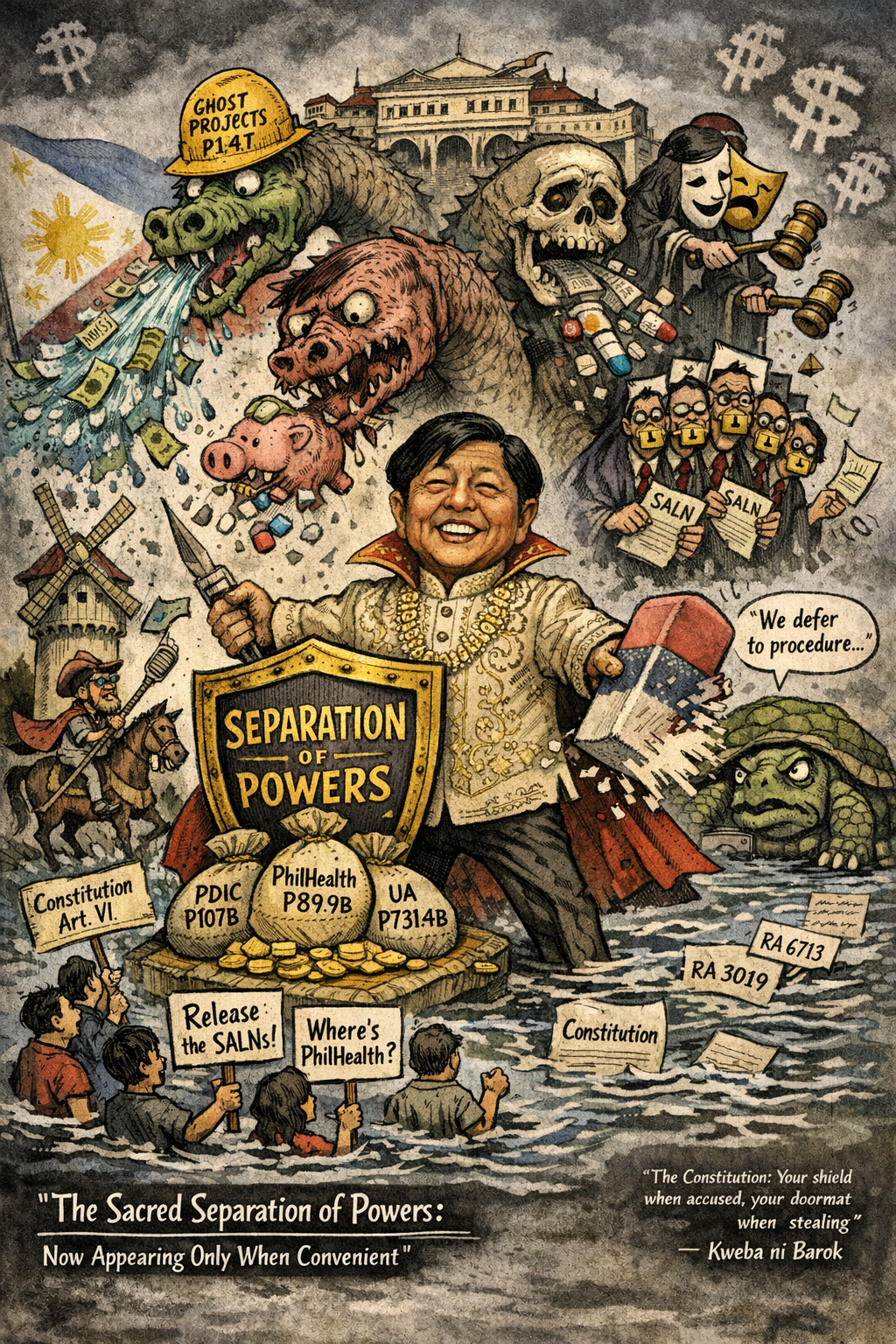

The Real Flood Control Failure: A Syndicate in Plain Sight

Let us stop pretending this is about one senator’s misfortune. This is systemic rot wearing a senatorial barong.

The DPWH has become the nation’s most lucrative milking cow, with “budget insertions” slipped into the national ledger like contraband. Politicians allegedly dictate projects, contractors pad costs, officials falsify completion, kickbacks flow upward.

Whistleblowers risk everything to expose it; Senate committees hold televised hearings that produce voluminous reports destined for archival oblivion. The Office of the Ombudsman swings into action with suspicious timing—sometimes lightning-fast, sometimes conveniently comatose—depending on who occupies Malacañang or who might run in the next election.

This is not mere incompetence. It is an ecosystem: lawmakers who insert, contractors who ghost-deliver, engineers who sign off, auditors who look away, prosecutors who calibrate speed to political temperature. And presiding over it all, a justice system that can detain a former senator in an hour yet takes decades to resolve agrarian reform cases.

Due Process: Shield of the Innocent or Maze for the Connected?

Kapunan invokes Article III, Section 1 of the 1987 Constitution with reverence. Who could argue? No one should be deprived of liberty without due process.

Yet in practice, due process in Philippine high-profile cases often functions less as shield than as labyrinth—designed to exhaust, delay, and ultimately defeat accountability.

Recall Allado v. Diokno (G.R. No. 113630, 1994): the Supreme Court voided a warrant issued without genuine judicial scrutiny of probable cause. In a similar vein, precedents such as Webb v. De Leon (G.R. No. 121234, 1995) and Mercado v. Court of Appeals (G.R. No. 109036, 1995) affirm that preliminary investigations, though summary and inquisitorial, must still provide the respondent a reasonable opportunity—after notice of the charges and the complainant’s evidence—to submit controverting proofs and protect against hasty, baseless prosecution.

So What? The Stakes and the Farce

If Revilla’s motions to quash succeed on technical grounds, expect triumphant press conferences, renewed showbiz-political ambitions, and another brick in the wall of public despair. Another high-profile corruption case dies not on lack of evidence, but on procedural niceties—the very niceties allegedly ignored when public money was looted.

The larger consequence is predictable: deepening cynicism. Every flood that inundates Bulacan homes will remind citizens that billions meant for mitigation vanished, while the alleged architects lecture us about constitutional rights.

Recommendations, then—sharp ones:

- Immediately declassify and publish the full Senate Blue Ribbon Committee draft report on the flood control scandal. No more selective leaks. Let the public see the names, amounts, and paper trail.

- Compel the Office of the Ombudsman and Sandiganbayan to hold a public press conference—not a canned statement, but one open to unscripted questions—explaining the “one-hour warrant” timeline in plain language, not legalese.

- Commission a truly independent audit of all flood control projects from 2021–2026, conducted by an international firm with no local ties, funded by sequestered assets of the accused if necessary.

- And if our domestic institutions prove structurally incapable of self-correction—as decades of evidence suggest—perhaps it’s time to invite the World Bank or an international anti-corruption body to oversee recovery of stolen funds. After all, we outsource everything else; why not accountability?

Because until the system stops treating public funds as private largesse and due process as a privilege of the powerful, the real flood—the one drowning Philippine democracy—will keep rising.

– Barok

If hypocrisy were taxable, we’d be the richest nation on earth.

Key Citations

A. Legal & Official Sources

- The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines.

- Revised Penal Code. Act No. 3815, Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, 8 Dec. 1930.

- Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. Republic Act No. 3019, Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, 17 Aug. 1960.

- Allado v. Diokno, G.R. No. 113630, 5 May 1994, Supreme Court of the Philippines, LawPhil Project.

- Webb v. De Leon. G.R. No. 121234, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 23 Aug. 1995. The LawPhil Project.

- Mercado v. Court of Appeals. G.R. No. 109036, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 5 July 1995. The LawPhil Project.

B. News Reports

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment