Enter Viado, Exit the Era of Looking the Other Way

By Louis “Barok” C. Biraogo — February 8, 2026

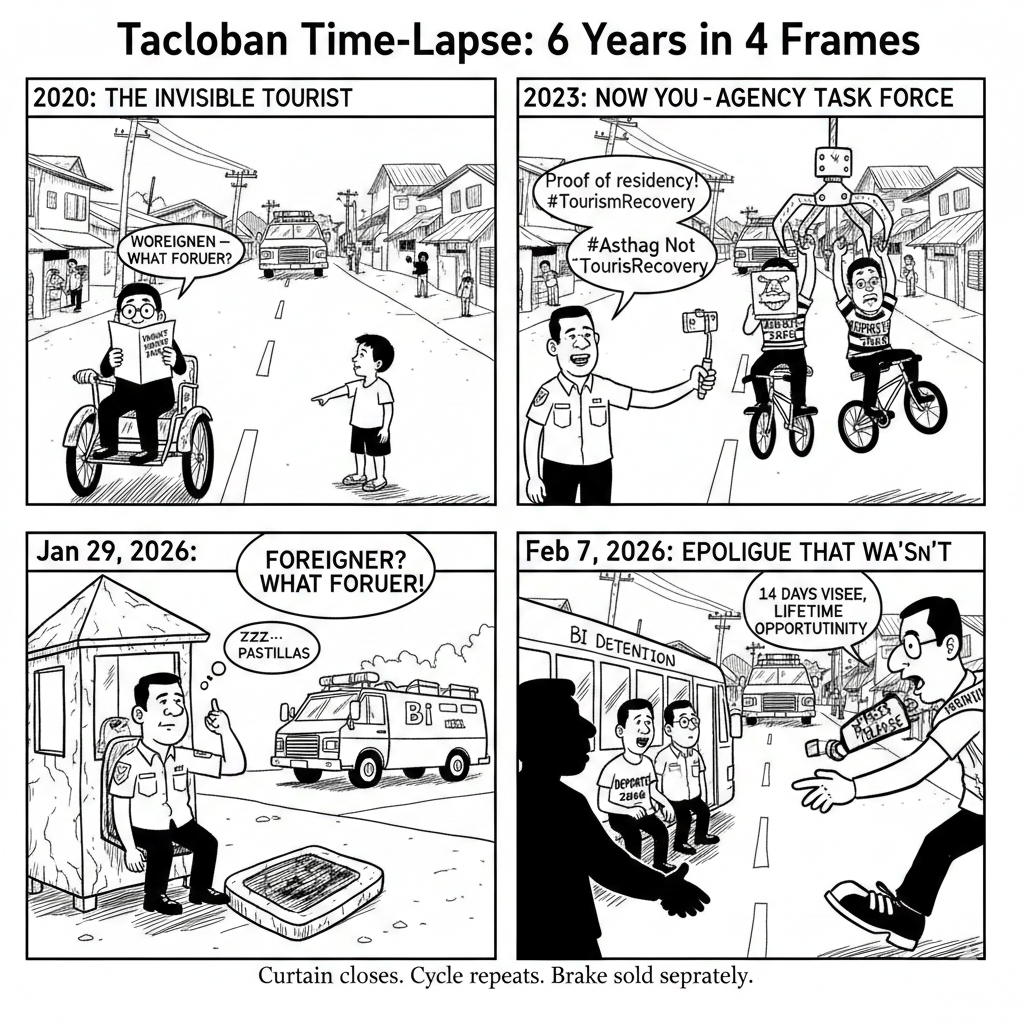

TWO Chinese nationals—Zhu Fulin, 51, and Wu Huoyan, 53—were dramatically arrested in Tacloban City on January 29, 2026, while tinkering with e-bikes in Barangay 91, Abucay. One had been overstaying since 2023, the other since 2020. One presented a Philippine Identification Card to pass himself off as a Filipino. Both were working without permits. They were whisked to Manila, detained, and now face deportation.

The Bureau of Immigration (BI) issued a press release. Commissioner Joel Viado thundered: “We will not tolerate foreigners who overstay, misrepresent themselves, or illegally engage in work at the expense of our laws and our people.”

Cue the applause. Or the laughter, depending on how long you’ve been watching this circus.

Let us dissect this carcass with the cold precision it deserves.

1. The Facade of Enforcement: A Case Study in Selective Theater

Barely two weeks after the Philippines rolled out a 14-day visa-free entry for Chinese nationals on January 16, 2026—ostensibly to juice tourism numbers—the BI staged a multi-agency takedown. The operation involved the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), the National Intelligence Coordinating Agency (NICA), the Intelligence Service of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (ISAFP), and local police. All this firepower for two middle-aged men selling e-bikes in Tacloban.

Is this decisive enforcement or political theater?

Let us be blunt. The immigration ecosystem in this country is less a well-oiled machine and more a termite-ridden bureaucracy that collapses only when someone shines a spotlight on it. The BI’s historical résumé includes the infamous “pastillas” scheme—where officers allegedly wrapped bribe money in paper like the sweet it was named after to escort Chinese nationals past immigration controls. That scandal implicated dozens of personnel. Reforms were promised. Heads rolled. And yet, here we are in 2026, still discovering overstayers who have evaded detection for three to six years.

The press release is a carefully staged production. The intended audience is not the Filipino public that genuinely fears job displacement or national security threats. The audience is the gallery on social media, the editorial boards, and the senators who keep asking why the new visa-free policy hasn’t yet produced another POGO-style invasion. The BI needs a scalp. Two scalps, actually. And the military-intelligence complex obliges with a show of force that screams: See? We are vigilant.

But if vigilance were real, Zhu and Wu would not have lasted years in Tacloban. This is not enforcement. This is damage control disguised as toughness.

2. Legal Vivisection: Statutes, Precedents, and Gap-ing Holes

Let us now wield the scalpel.

Under Commonwealth Act No. 613 (the Philippine Immigration Act of 1940, still stubbornly clinging to life):

- Section 37(a)(7): An alien who remains in the Philippines after the expiration of his visa or without valid documents is deportable. Zhu has no documents at all; Wu has been illegal since 2020. Clear violation.

- Section 37(a)(4): An alien who engages in employment without BI and Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) authorization is deportable. Both were working in an e-bike shop on tourist status. Clear violation.

- Section 37(a)(1): An alien who obtains admission through fraud or willful misrepresentation is deportable. Wu’s presentation of a PhilID is not merely a desperate bluff—it is a criminal act that bleeds into the Revised Penal Code (RPC).

Article 172 of the RPC punishes falsification of public documents by a private individual with prisión correccional in its medium and maximum periods and a fine. Why has the BI not initiated a parallel criminal complaint? Are they asleep at the wheel, or deliberately avoiding the messier path?

And then there is the Filipino employer—the ghost in this narrative. Under the Labor Code of the Philippines (Presidential Decree No. 442, as amended) and DOLE Department Order No. 186-17, the primary violator for illegal alien employment is the employer, not the alien. The employer faces fines up to ₱100,000 per alien, possible license revocation, and criminal liability. Yet the press release names no employer. The news report names no employer. Why? Because prosecuting a local businessman is far less photogenic than parading two Chinese nationals before the cameras.

Supreme Court precedents are not mere footnotes—they are weapons.

In Carlos T. Go, Sr. v. Luis T. Ramos (G.R. No. 167569, 2009), the Court upheld deportation for misrepresentation of citizenship. In Tung Chin Hui v. Rodriguez (G.R. No. 141938, 2001), tampered passports justified summary deportation. Yet both cases affirm that summary deportation is a get-out-of-jail-free card for the State—it avoids the burden of criminal prosecution while neatly disposing of the alien.

Board of Commissioners v. Yuan Wenle (G.R. No. 242957, 2023) confirms that administrative warrants are sufficient for deportation proceedings, provided due process—particularly the requirement of reasonableness—is upheld. But due process for whom? The alien gets a hearing before the BI Board of Commissioners. The Filipino employer gets silence.

And then there is the loophole economy. The BI itself has been whining to Congress about “legal loopholes” that allow lawyers to file endless motions, TROs, and appeals to delay deportation indefinitely. The law, as Dickens might say, is an ass—and in this country, it is an ass that protects the brazen violator while the ordinary overstayer languishes.

3. Prosecution Pathways: From Slap-on-the-Wrist to Full-Bore Scorched Earth

Here are the roads available, ranked from most likely to most severe:

- Administrative Deportation (Most Likely)

Agency: BI

Burden: Preponderance of evidence

Timeline: 30–90 days (appealable to Department of Justice (DOJ), then courts)

Outcome: Deportation, fines (₱500/month overstay), possible blacklisting

Diplomatic friction: Minimal - Criminal Prosecution for Falsification (Wu only)

Agency: Tacloban City Prosecutor → DOJ → RTC

Burden: Proof beyond reasonable doubt

Timeline: 1–3 years

Outcome: Imprisonment (up to 6 years), then deportation

Diplomatic friction: Moderate—China may protest detention - Labor Code Violations Against Employer

Agency: DOLE

Burden: Substantial evidence

Timeline: 6–18 months

Outcome: Fines, business closure, criminal referral

Diplomatic friction: None (local target) - Syndicate/Espionage Charges (Least Likely)

Agency: Philippine National Police (PNP)-NCID, NICA, DOJ

Burden: Beyond reasonable doubt

Timeline: Years

Outcome: Long imprisonment, major diplomatic row

Diplomatic friction: Severe

4. The Ecosystem of Scandal: Rumors, Patterns, and Unasked Questions

This is not an isolated incident. Under Commissioner Joel Viado’s leadership, the Bureau of Immigration deported 1,422 aliens in the first half of 2025 alone—more than double the number from the previous year—marking one of the most aggressive crackdowns on immigration violations in recent memory. Chinese nationals dominate the deportation list, and provinces from Pangasinan to Eastern Samar have witnessed a steady stream of similar arrests. The pattern is painfully clear: overstaying, fake documents, unauthorized retail and service businesses. Yet credit where it’s due—Viado has at least turned the numbers into something the BI can finally point to with pride, even if the deeper systemic rot remains untouched.

The e-bike angle is particularly ripe. Globally, Chinese e-bike manufacturers have been sued for fraudulent safety certifications. In the Philippines, whispers link some Chinese-run e-bike shops to money laundering or remnants of the POGO ecosystem. Mom-and-pop front or syndicate node? The BI is not telling.

The involvement of NICA and ISAFP raises eyebrows. Is this really about two men selling bicycles, or is it bureaucratic empire-building in the shadow of West Philippine Sea tensions?

And the hypocrisy is galling. Wealthy, well-connected overstayers from “preferred” nationalities—Europeans running bars in Boracay, Americans married to Filipinas but never bothering with paperwork—rarely make the front page. The ideal enemy alien, it seems, is always the one who fits the current political narrative.

5. Actors & Resolutions: A Game of Legal and Political Chess

- Commissioner Viado and the BI: Pursuing swift deportation delivers clear statistics and reinforces the message of firm enforcement—outcomes that benefit both the agency’s record and public confidence. Referring the case for criminal prosecution could lead to a longer, more complex process that might highlight gaps in earlier monitoring efforts. Viado’s supporters clearly hope this signals the start of a stronger, more consistent crackdown rather than a one-off headline.

- Zhu and Wu: Voluntary departure (pay fines, leave quietly) is the smart retreat. Fighting deportation through appeals buys time but rarely wins. Asylum claims are laughable.

- The Unnamed Employer: The critical void. If Filipino, political connections may shield him. If another alien, the plot thickens. Silence suggests either a sealed investigation or a glaring omission.

- Chinese Embassy: Past precedent shows quiet consular assistance, no public protest unless detention drags on.

Plausible resolutions:

- Banal: Quiet deportation within 60 days, blacklisting, story dies.

- Moderate: Criminal inquest for Wu’s falsification, plea deal, serve short sentence, deport.

- Escalatory: Investigation expands to employer and document syndicate, multiple arrests.

- Seismic: Trial reveals BI officers in Tacloban or Manila turned blind eyes for years—another “pastillas” exposé.

6. The Barricades of Reform: Calls to Action Anchored in Law

Enough dissection. Time for the manifesto.

Commissioner Viado, these are practical, legally anchored suggestions worth pursuing:

- Invoke Republic Act No. 6770. Demand the Office of the Ombudsman investigate not only Zhu and Wu, but every BI officer whose jurisdiction they evaded for years—from Tacloban to Manila. Sunlight is the best disinfectant.

- Urge the Tacloban City Prosecutor to conduct an immediate inquest for falsification of public documents against Wu Huoyan under RPC Article 172. No more selective mercy.

- Compel DOLE to audit every e-bike shop, retail establishment, and similar business in Tacloban and nearby provinces for illegal alien employment. Article XII, Section 12 of the 1987 Constitution demands prioritization of Filipino labor. Act like you believe it.

- Propose concrete amendments:

- Mandatory DOJ criminal referral for any overstay exceeding one year or involving fraud.

- A public online registry of employers sanctioned for hiring illegal aliens.

- Strip the BI of sole prosecutorial discretion in fraud cases; route them directly to the DOJ.

If this arrest marks the beginning of genuine, sustained reform under Commissioner Viado’s leadership, then it deserves full support—especially if future headlines show concrete next steps, such as “BI Refers Filipino Employer to DOJ for Prosecution” or “Ombudsman Reviews Compliance in Tacloban Operations.”

Should these follow-up actions materialize, it would signal real progress rather than isolated enforcement. Until then, the public will rightly look for evidence that this is more than a single high-profile operation.

The law is our weapon. Let us wield it without fear or favor.

From the shadows of selective enforcement, this is your regularly scheduled reality check.

— Barok,

because someone has to say the quiet part out loud.

Key Citations

A. Legal & Official Sources

- Commonwealth Act No. 613: An Act to Control and Regulate the Immigration of Aliens into the Philippines. 26 Aug. 1940. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines.

- The Revised Penal Code. Act No. 3815, The LawPhil Project.

- Labor Code of the Philippines. Presidential Decree No. 442, as amended, The LawPhil Project.

- Philippines, Department of Labor and Employment. Department Order No. 186, Series of 2017: Revised Rules for the Issuance of Employment Permits to Foreign Nationals. 16 Nov. 2017. Department of Labor and Employment.

- The Ombudsman Act of 1989. Republic Act No. 6770, The LawPhil Project.

- The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines. Article XII, Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines.

- Carlos T. Go, Sr. v. Luis T. Ramos. G.R. No. 167569, 4 Sept. 2009, The LawPhil Project

- Tung Chin Hui v. Rodriguez. G.R. No. 141938, Supreme Court E-Library.

- Board of Commissioners of the Bureau of Immigration v. Yuan Wenle. G.R. No. 242957, 28 Feb. 2023, The LawPhil Project.

B. News Reports

- “2 overstaying Chinese nationals arrested in Tacloban.” Philippine News Agency, 6 Feb. 2026.

- Santos, Eimor P. “CA upholds dismissal of BI official in ‘pastillas’ scheme.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 7 Jul. 2025.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment