What Happens When Foreign Policy Becomes Performance Art and Nobody Remembers We’re the Weaker Party

By Louis “Barok” C. Biraogo — February 16, 2026

I. THE SETUP: A TALE OF TWO EGOS AND A SEA OF TROUBLES

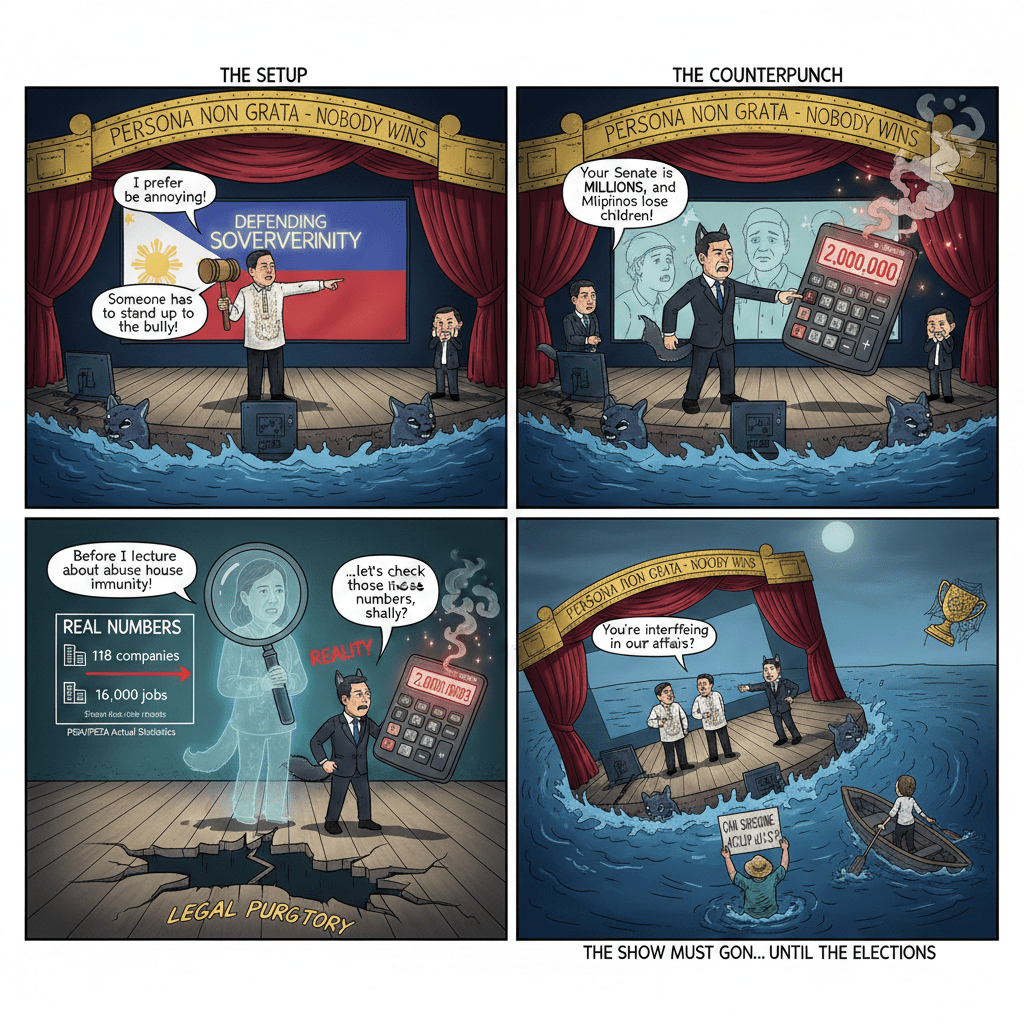

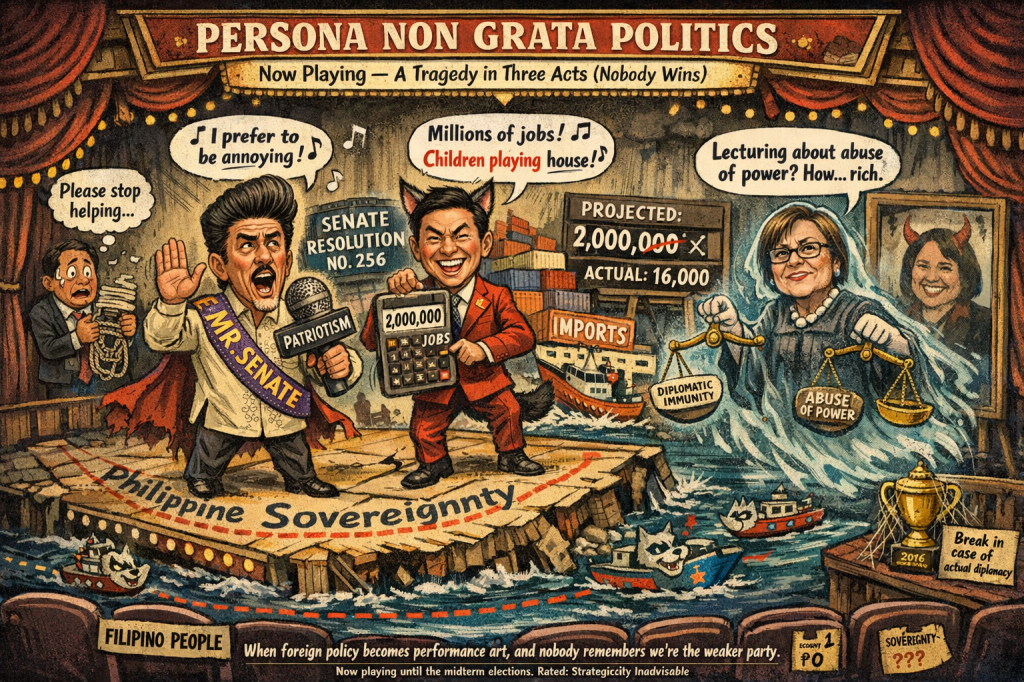

Picture this: In one corner, we have Senate President Vicente “Tito” Sotto III, a man whose political career has spanned decades and whose capacity for theatrical indignation remains undiminished by time. In the other corner, Chinese Embassy spokesperson Ji Lingpeng, wielding the rhetorical sledgehammer of “wolf warrior diplomacy” with all the subtlety of a karaoke singer at 3 AM. Between them? The ghost of Senator Leila de Lima, rising from her own legal purgatory to lecture foreign diplomats about the abuse of immunity—a spectacle so rich in irony it could fund its own infrastructure project.

The stage is the West Philippine Sea, that body of water where Philippine sovereignty goes to die a thousand cuts by Chinese maritime militia vessels. The props include Senate Resolution No. 256, which condemned the Chinese Embassy for having the temerity to criticize Philippine officials defending national territory. The embassy’s response? A threat that escalating this diplomatic tiff could cost “millions of jobs” for Filipinos.

Let that sink in. Millions. Of jobs.

We’ll return to that mathematical unicorn shortly. But first, let’s understand what we’re really watching here: Is this a principled stand for sovereignty, grounded in the 2016 Arbitral Award that invalidated China’s nine-dash line? Or is it a dress rehearsal for the 2028 presidential elections, where senators compete to see who can out-patriot each other while the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) watches in horror, clutching its carefully crafted diplomatic cables like a priest clutching rosary beads during an exorcism?

The answer, dear reader, is probably both. And that’s precisely the problem.

This isn’t just about whether a Chinese diplomat gets declared persona non grata. This is about whether the Philippines can assert its maritime rights under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) without China holding our economy hostage. It’s about whether our senators understand that diplomacy is not performance art. And it’s about whether we’ve learned anything from the past decade of being bullied in our own waters while our government issues “strongly worded statements” that accomplish precisely nothing.

Sotto’s response to the Chinese Embassy’s initial criticism was characteristically Sotto: “When someone triggers you to react and you do not, it’s annoying! I prefer to be annoying!” A man of principle, clearly. Or a man who understands that looking tough on China plays well with voters who are tired of watching their fishermen get harassed by vessels that belong to a “fishing militia” the way the Philippine Navy belongs to a knitting circle.

But here’s where it gets interesting—and by interesting, I mean legally and diplomatically perilous. The Chinese Embassy didn’t just respond; they escalated. They invoked economic consequences. They called our senators children “playing house.” And in doing so, they may have crossed the line from legitimate diplomatic communication into what international law politely calls “interference in internal affairs.”

Or did they?

Welcome to the legal colosseum, where the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations meets schoolyard insults, and nobody emerges with their dignity intact.

II. THE LEGAL COLOSSEUM: PITTING THE VIENNA CONVENTION AGAINST “HE SAID, SHE SAID”

Let’s start with the legal bedrock upon which this entire circus rests: the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (1961), or VCDR for those of us who prefer our international law in acronym form. Both the Philippines and China are parties to this treaty, which means both are theoretically bound by its provisions. I say “theoretically” because, as we’re about to see, the gap between treaty obligations and actual conduct is wide enough to park a Chinese maritime militia vessel.

The Senate’s Case: VCDR Article 41(1) and the Art of Not Interfering

The Senate’s legal argument, insofar as 15 senators signing a resolution constitutes a “legal argument,” rests primarily on Article 41(1) of the VCDR:

“Without prejudice to their privileges and immunities, it is the duty of all persons enjoying such privileges and immunities to respect the laws and regulations of the receiving State. They also have a duty not to interfere in the internal affairs of that State.”

Now, this is where things get interesting. What constitutes “interference in internal affairs”? The VCDR doesn’t define it, which is convenient for everyone except people trying to apply it. But let’s apply some basic legal reasoning here—always a dangerous proposition in Philippine politics, but bear with me.

The Chinese Embassy issued public statements criticizing Philippine officials for defending sovereignty claims. Then, when senators threatened to recommend declaring a diplomat persona non grata, the embassy doubled down by:

- Publicly warning of economic consequences (“millions of jobs”)

- Insulting the institutional capacity of legislators (“children playing house”)

- Attempting to dictate the boundaries of legislative action (only the executive can declare PNG)

Let’s take these one by one, because this is where the Senate actually has a point—buried somewhere beneath the political grandstanding.

First, warning that diplomatic actions will have economic consequences is technically legitimate state-to-state communication. Countries signal consequences all the time. But there’s a difference between private diplomatic communication and public economic threats designed to influence domestic political processes. When an embassy spokesperson tells the media that legislative actions will cost jobs, they’re not communicating with the executive branch—they’re communicating directly with Filipino voters, over the heads of their elected representatives. That’s not diplomacy; that’s lobbying. And when foreign governments lobby domestic populations to pressure their legislators, we call that interference.

The 2016 Arbitral Award, which China rejects but which remains legally binding under UNCLOS Annex VII, established that the Philippines has sovereign rights in the West Philippine Sea. Senators defending this position are engaging in legitimate legislative activity—expressing the sense of the Senate on matters of national sovereignty. The Chinese Embassy’s public campaign to suppress this legislative speech through economic intimidation crosses the line from permissible diplomatic communication to impermissible interference in domestic political processes.

Or put more simply: You can tell our government what you think. You cannot threaten our people to get our government to shut up.

Second, the “children playing house” comment deserves special recognition as perhaps the most diplomatically inept utterance of 2026, and we’re only in February. Article 41(1) requires diplomats to “respect the laws and regulations of the receiving State.” While this primarily refers to written laws, the spirit of the VCDR—embodied in its preamble and the principle of comity—requires mutual respect between diplomatic missions and host governments. Publicly insulting the intellectual capacity of a co-equal branch of government violates this principle so egregiously that it’s almost impressive.

To put this in perspective: Imagine if a Philippine diplomat in Beijing publicly called members of the National People’s Congress “children playing house.” How long do you think that diplomat would remain in China? I’ll save you the suspense: approximately 37 seconds, or however long it takes to print an expulsion order.

Third, the embassy’s insistence that “only the executive can declare PNG” is technically correct—the best kind of correct, if you’re a lawyer arguing a losing case. Article 9 of the VCDR states:

“The receiving State may at any time and without having to explain its decision notify the sending State that any member of the diplomatic staff is persona non grata.”

Note the subject: “the receiving State”—not “the legislature of the receiving State.” Under the Philippine Constitution, foreign affairs are an executive function (Article VII, Section 21). The Supreme Court affirmed this in Bayan v. Zamora: the President conducts foreign relations, while the Senate’s role is limited to treaty concurrence.

So yes, the Chinese Embassy is correct that senators cannot themselves declare a diplomat PNG. But here’s what makes this argument utterly beside the point: nobody claimed they could. The senators discussed recommending PNG declaration to President Marcos. That’s called legislative advocacy, and it’s perfectly constitutional. The Chinese Embassy’s attempt to silence even this discussion by calling it illegitimate reveals the true nature of their objection: they don’t want Philippine legislators talking about Chinese diplomats at all, regardless of constitutional propriety.

And that, dear reader, is the textbook definition of interference in internal affairs.

The Chinese Embassy’s Case: VCDR Article 9 and the Right to State Positions

Now, in fairness—and I dispense fairness sparingly, so treasure this moment—the Chinese Embassy does have some legitimate legal ground to stand on. Let’s examine it before we burn it down.

Article 9 does indeed reserve PNG declarations to the executive. The embassy’s observation that this is not a legislative power is constitutionally sound. Under Philippine law, as established in WHO v. Aquino (1972) and DFA v. NLRC (1993), questions of diplomatic immunity and status are “political questions” reserved to the executive branch. Courts—and by extension, other branches—must defer to the DFA’s determination to avoid embarrassing foreign relations.

So when senators threaten PNG declarations, they’re engaging in what lawyers call “advisory resolutions”—expressions of legislative sentiment with no legal force. The Chinese Embassy is within its rights to point this out.

Moreover, diplomatic missions have a right to communicate publicly. Nothing in the VCDR prohibits embassies from issuing press statements, holding press conferences, or engaging with media. If we’re going to argue that the Chinese Embassy cannot criticize Philippine officials, we’d have to apply that standard universally—which would mean Philippine embassies abroad couldn’t issue statements either. That’s not a standard any country would accept.

And finally, warning about the economic consequences of diplomatic downgrading is technically permissible policy signaling. When the U.S. warns countries about the consequences of trade policy, when the EU conditions market access on regulatory compliance, when the IMF attaches conditions to loans—these are all forms of economic signaling tied to political relations. China doing the same isn’t per se illegal.

But Here’s Where the Embassy’s Case Collapses Like a Poorly Built DPWH Bridge

The problem isn’t that China communicated a position. The problem is how they communicated it, to whom, and for what purpose.

When Ji Lingpeng tells the media that Senate actions will cost “millions of jobs,” he’s not engaging in government-to-government diplomacy. He’s engaging in what we might generously call “public intimidation” and what we might more accurately call “attempting to turn the Filipino electorate against their own representatives through economic fear.”

This violates the spirit of Article 41(1) in at least three ways:

- It attempts to pressure domestic political processes through public economic threats rather than diplomatic channels

- It disrespects the institutional role of a co-equal branch of the Philippine government

- It abuses the privilege of diplomatic immunity to engage in advocacy that would be illegal for a foreign entity without immunity

On that last point, Senator de Lima—and I never thought I’d type these words—is actually correct. Under Philippine law, foreign nationals and entities cannot engage in political advocacy. They cannot fund campaigns, endorse candidates, or attempt to influence domestic political processes. The reason diplomatic missions can issue public statements is because of their immune status under the VCDR.

But immunity is not a license for abuse. Article 32 of the VCDR allows sending states to waive immunity, and Article 9 allows receiving states to declare diplomats PNG precisely because immunity can be abused. When diplomats use their immune status to engage in conduct that would be illegal for non-immune actors—in this case, foreign interference in domestic politics—they abuse their privilege.

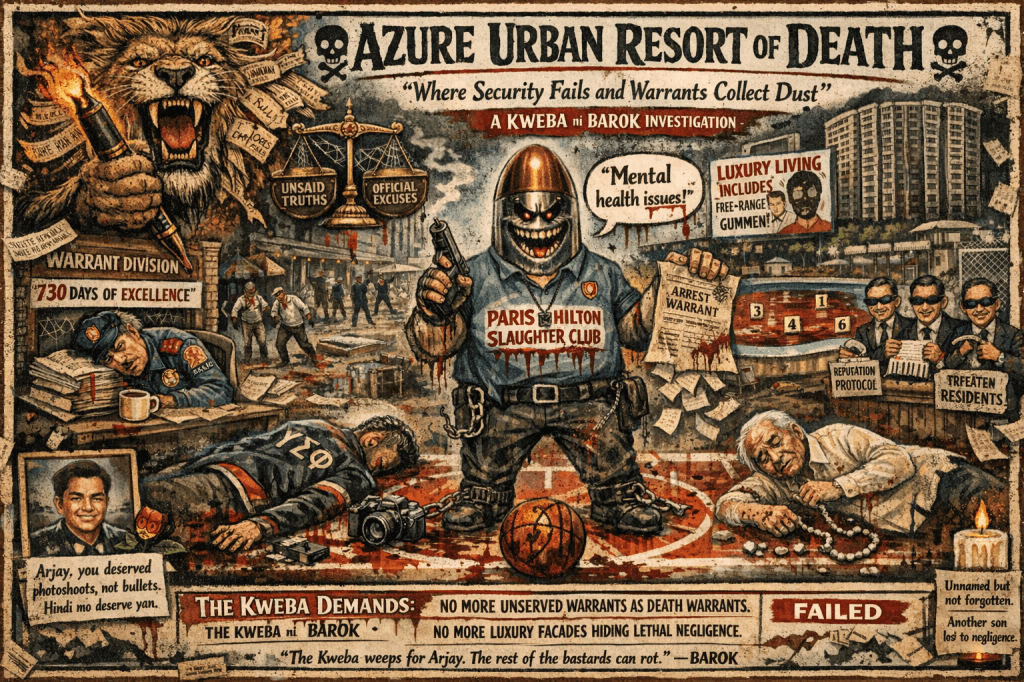

Now, here’s where the irony gets so thick you could cut it with a balisong: Leila de Lima lecturing anyone about the abuse of power is like Imelda Marcos lecturing anyone about shoe budgets. During her tenure as Justice Secretary, de Lima was not exactly a champion of free speech or civil liberties. Her prosecution of political opponents, her role in the Hacienda Luisita massacre investigation, her weaponization of the DOJ—these are not the credentials of a free speech advocate.

But even a stopped clock is right twice a day, and even Leila de Lima can stumble into a correct legal position occasionally. Her point about diplomatic immunity being abused is valid, even if it’s coming from someone whose own record on respecting legal process is, shall we say, checkered.

The UNCLOS and Arbitral Award Dimension: Legal Bedrock or Political Theater?

We can’t discuss the legal framework without addressing the elephant in the room—or more accurately, the nine-dash line in the sea. The 2016 Arbitral Award under UNCLOS Annex VII ruled that:

- China’s nine-dash line claim has no legal basis

- China violated Philippine sovereign rights in the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)

- China’s artificial island building violates UNCLOS

This award is legally binding under international law. China’s rejection of it doesn’t change its legal status any more than my rejection of my mortgage changes my debt status.

The Senate’s defense of sovereignty claims in the WPS is grounded in this award and in UNCLOS Articles 2-3 (territorial sea sovereignty) and Articles 55-75 (EEZ rights). Republic Act No. 12064 (Philippine Maritime Zones Act) codifies these claims into domestic law.

So when senators pass resolutions defending Philippine sovereignty, they’re not engaged in political theater—or at least, they’re not only engaged in political theater. They’re affirming legal positions grounded in binding international law.

The Chinese Embassy’s criticism of these positions is therefore not just undiplomatic; it’s legally baseless. They’re asking Philippine legislators to refrain from defending legal rights established by international arbitration. That’s not diplomacy; that’s asking us to surrender sovereignty by silence.

The Verdict: Both Sides Are Legally Correct, Which Means Both Are Wrong

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: both the Senate and the Chinese Embassy are operating within the technical bounds of international law, which means international law is about as useful here as a screen door on a submarine.

The Senate has the constitutional right to pass resolutions expressing legislative sentiment. The Chinese Embassy has the right to issue public statements. Neither has violated any specific provision of the VCDR or Philippine law in a way that would be actionable in court.

But both have violated the spirit of diplomatic relations, which requires mutual respect, restraint, and a recognition that some things are better said in private than screamed in public.

The Senate’s threat of PNG declarations is grandstanding that undermines the executive’s ability to manage foreign relations coherently. The Chinese Embassy’s public economic threats are interference that crosses the line from diplomacy to intimidation.

And we, the Filipino people, are caught in the middle—watching our sovereignty get litigated in the court of public opinion while our government figures out whether it’s more afraid of looking weak or going broke.

Spoiler alert: it’s both.

III. THE NUMBERS GAME: DECONSTRUCTING THE “MILLIONS OF JOBS” THREAT

Now we arrive at my favorite part of this farce: the claim that escalating diplomatic tensions will cost “millions of jobs” for Filipinos. This assertion, delivered with the confidence of a man who has never actually looked at Philippine employment statistics, deserves the kind of mathematical vivisection usually reserved for pyramid schemes and cryptocurrency whitepapers.

Let’s start with what we know, using actual data rather than the fevered imaginings of diplomatic spokespersons.

The Actual Numbers: A Reality Check

According to the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) and Philippine Economic Zone Authority (PEZA):

- 118 Chinese companies operate in Philippine economic zones

- These companies provide 16,000 direct jobs

- They generated $406 million in exports (mid-2025 data)

- Chinese investment pledges in 2025: P10.25 billion (3.68% of total foreign pledges)

- China ranks 7th among investment sources (behind Singapore, Netherlands, Japan, South Korea, Cayman Islands, and the US)

Now, let’s do some back-of-the-napkin math that Ji Lingpeng apparently couldn’t be bothered with:

If 118 companies provide 16,000 direct jobs, that’s an average of 136 jobs per company. To reach “millions of jobs”—let’s be conservative and say 2 million—you’d need either:

- 14,706 Chinese companies at current employment rates, or

- Each current company to employ 16,949 workers (a 12,343% increase)

Neither scenario bears any resemblance to reality.

“But wait!” I hear the apologists cry. “What about indirect employment? Supply chains! Multiplier effects!”

Fair point. Let’s be generous and apply a 5:1 multiplier (absurdly high, but let’s humor them). That gives us 80,000 jobs—direct and indirect—tied to Chinese companies in PEZA zones.

Still not “millions.” Not even close. To reach 2 million with a 5:1 multiplier, you’d need 400,000 direct jobs from Chinese investment. We have 16,000.

Trade: The Bigger Picture, Still Not “Millions”

Perhaps Ji is counting jobs tied to trade rather than investment. Let’s examine:

- China is the Philippines’ top import source: $38.22 billion (28.6% of imports)

- Exports to China: $9.30 billion (11% of total exports)

Jobs tied to exports are easier to calculate. Using the Department of Trade and Industry’s rule of thumb (every $100,000 in exports supports approximately 1 job), $9.3 billion in exports supports roughly 93,000 jobs.

Jobs tied to imports are harder to quantify because imports generally displace domestic jobs rather than create them. But let’s be absurdly generous and assume import-related jobs (logistics, warehousing, retail) at a 1:10 ratio of export jobs. That adds another 9,300 jobs, for a total of approximately 102,000 jobs tied to Philippine-China trade.

Add investment jobs (80,000 with our generous multiplier) and trade jobs (102,000), and you get 182,000 jobs potentially at risk from a complete collapse of economic relations.

Still not “millions.” And this assumes:

- Complete cessation of all trade (unlikely)

- No substitution by other trading partners (false)

- No domestic production to replace Chinese imports (false)

- China willing to sacrifice $9.3 billion in Philippine exports and billions in import revenue (unlikely)

The Bank of America Warning: Real But Not Apocalyptic

The 2024 BofA warning about economic damage from WPS tensions is real, but let’s read what it actually says:

“The decline in Philippines exports to China, tourism and investment from China appears worse than with the rest of the world.”

Translation: Relations are already deteriorating, and it’s hurting—but it’s marginal deterioration, not collapse. BofA wasn’t warning about “millions of jobs”; they were noting that Chinese investment, already modest (3.68% of total FDI pledges), could have been higher if not for tensions.

This is the economic equivalent of saying “You could have won the lottery if you’d bought a ticket.” True, but not exactly a compelling basis for foreign policy.

What China Is Really Threatening

Here’s what China could realistically do if they wanted to inflict economic pain:

- Slow-roll import permits for Philippine agricultural goods (bananas, pineapples, coconuts)

- Reduce tourist arrivals (though Chinese tourism has already declined due to tensions)

- Delay infrastructure projects (Kaliwa Dam, other Belt and Road Initiative projects—most of which are mired in feasibility studies anyway)

- Impose targeted sanctions on specific Philippine exports or companies

The total economic impact? Economists estimate a worst-case scenario of 0.5-1.0% of GDP annually—painful, but not catastrophic. For context, the Philippines grew 5.6% in 2024 despite ongoing WPS tensions.

Moreover, this assumes the Philippines just sits there and takes it. In reality, the Philippines could:

- Diversify trade to Japan, South Korea, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) partners, and the US

- Attract investment from competitors eager to gain market share (Vietnam did exactly this during US-China trade tensions)

- Leverage alliances for economic support (the US and Japan have both signaled willingness to deepen economic ties)

The “Millions” Claim: A Mythical Creature

So where does Ji’s “millions of jobs” figure come from? My professional assessment, based on rigorous economic analysis: he made it up.

Or more charitably, he’s engaging in what diplomats call “signaling” and what normal people call “bullshitting.” The purpose isn’t to convey accurate information; it’s to create fear. If Filipino voters believe that standing up for sovereignty will cost them their livelihoods, they’ll pressure their representatives to back down.

It’s economic coercion dressed up as economic analysis. And it’s deeply offensive—not just to Filipinos, but to mathematics.

Here’s the real economic picture: China is an important trading partner, but not an irreplaceable one. The Philippines is more dependent on China for imports than China is on the Philippines for exports. But the relationship is not one-way. China benefits from:

- Access to a growing consumer market (110 million Filipinos with rising incomes)

- Strategic positioning in Southeast Asia

- Natural resources (nickel, copper, tropical agricultural products)

- A hedge against US-dominated supply chains

A complete breakdown in economic relations would hurt both sides. The question is: who can endure the pain longer?

Given that China is trying to project regional dominance while managing a property crisis, youth unemployment, and demographic decline, while the Philippines is experiencing steady GDP growth, a demographic dividend, and strengthening alliances—I’d say the strategic position isn’t as lopsided as Ji would have us believe.

The Barok Calculator: What Jobs Are Actually at Risk?

Let me give you the realistic worst-case scenario, using actual data:

- Direct PEZA jobs: 16,000

- Export-related jobs: 93,000

- Import/logistics jobs: 10,000

- Tourism jobs (if Chinese tourism drops to zero): 15,000

- Infrastructure project jobs (if all projects cancelled): 5,000

Total potentially at risk: 139,000 jobs

That’s significant. That’s not nothing. But it’s not “millions.” It’s not even “one million.” It’s 0.29% of the Philippine labor force (48 million employed Filipinos).

And this assumes:

- Total economic decoupling (will not happen)

- No substitution by other partners (will absolutely happen)

- No government intervention or support (unlikely)

The realistic figure is probably 50,000-70,000 jobs at risk in a serious deterioration of relations—painful for those affected, but manageable at a macroeconomic level.

The Verdict: Economic Coercion Disguised as Economic Analysis

Ji Lingpeng’s “millions of jobs” warning is not economic analysis. It’s economic warfare by other means. It’s an attempt to weaponize Filipino workers’ livelihoods to pressure their government into surrendering sovereign rights.

And the most insulting part? He apparently thinks we’re too stupid to check the numbers.

Newsflash, Mr. Ji: We have calculators. We have government statistics. We have functioning brains. And when we use them, your “millions of jobs” claim dissolves faster than Chinese-built infrastructure during typhoon season.

The real question isn’t whether China can hurt the Philippine economy—they can, marginally. The real question is whether the Philippines should surrender its sovereignty to avoid that marginal economic pain.

And the answer to that question isn’t economic; it’s political, strategic, and moral.

Which brings us to the diplomatic chessboard—or as I like to call it, “How to Play 4D Chess When Your Opponent Is Playing Hungry, Hungry Hippos.”

IV. THE DIPLOMATIC CHESSBOARD (OR, HOW TO PLAY 4D CHESS WHEN YOUR OPPONENT IS PLAYING “HUNGRY, HUNGRY HIPPOS”)

Welcome to the strategy section, where we attempt to apply game theory to a situation in which one player thinks they’re playing Game of Thrones while the other is playing Tong-Its at a Barangay wake. The fundamental challenge of Philippine-China relations is that we’re operating under completely different strategic frameworks, with completely different objectives, and completely different understandings of what victory looks like.

For China, this is about regional hegemony, historical grievances dating back to the “century of humiliation,” and establishing a sphere of influence that pushes back against US dominance in Asia. For the Philippines, this is about whether our fishermen can catch fish without being harassed by “maritime militia” vessels that are about as civilian as the People’s Liberation Army Navy.

These are not commensurate objectives, which makes negotiation fascinating and resolution nearly impossible.

But let’s analyze the options available to each side, the likely outcomes, and the strategic wisdom (or lack thereof) behind each move.

The Philippines’ Moves: A Menu of Bad Options

The Philippines finds itself in a classic strategic dilemma: every option carries significant downsides, and doing nothing is itself a choice with consequences.

Option 1: The “Persona Non Grata” Declaration

This is the option that’s currently being discussed, debated, and deployed as a political cudgel by senators who understand that looking tough on China plays well with voters who are tired of getting bullied in their own territorial waters.

The Case For:

- Sends a clear signal that the Philippines will not tolerate diplomatic overreach

- Reasserts Philippine sovereignty and institutional dignity

- Satisfies domestic political pressure for a strong response

- Falls within the Philippines’ sovereign rights under VCDR Article 9

The Case Against:

- Triggers reciprocal expulsion of Philippine diplomats from China

- Poisons diplomatic channels precisely when they’re most needed

- Gives China a propaganda victory (“See? The Philippines is the aggressor!”)

- Undermines the DFA’s “firm but professional” strategy

- Potentially triggers economic retaliation (even if not “millions of jobs”)

Barok’s Assessment: This is the diplomatic equivalent of feeling good about yourself while making your situation objectively worse. Yes, it’s satisfying. Yes, it’s within our rights. Yes, it will play well in the next election cycle. But it accomplishes nothing except to escalate tensions with a neighbor who has more money, more weapons, and less concern about looking reasonable.

The fundamental problem with the PNG strategy is that it treats a symptom rather than the disease. The disease is China’s refusal to respect the 2016 Arbitral Award and continued harassment in the West Philippine Sea. Expelling a diplomat doesn’t address any of that; it just makes us feel better about being unable to address it.

Option 2: The DFA’s “Firm but Professional” Approach

This is the strategy currently being advocated by DFA spokesperson Rogelio Villanueva Jr., and it deserves more credit than it’s getting from senators eager to score political points.

The Strategy:

- Continue diplomatic engagement through proper channels

- Maintain UNCLOS-based legal position consistently

- Avoid public escalation while protecting core interests

- Pursue ASEAN Code of Conduct negotiations

- Strengthen security partnerships (US, Japan) as deterrence

- Keep economic channels open where possible

The Case For:

- Preserves diplomatic options and flexibility

- Maintains moral high ground internationally

- Allows for backchannel negotiations without loss of face

- Consistent with successful strategies used by other ASEAN states

- Reduces risk of economic retaliation

- Keeps focus on long-term strategic positioning rather than short-term political theater

The Case Against:

- Looks weak domestically to voters who want to see action

- Allows China to continue current behavior without immediate consequences

- Requires patience that Philippine politics rarely rewards

- Depends on ASEAN unity that may not materialize

- May be interpreted by China as weakness, inviting further aggression

Barok’s Assessment: This is the correct strategic approach, which means it has approximately zero chance of being politically sustainable. The DFA’s strategy is what you do when you’re a small country dealing with a powerful bully: you document everything, you build alliances, you maintain legal high ground, and you wait for opportunities to advance your position incrementally.

The problem is that “incremental advancement” doesn’t win elections. “Standing up to China” does. Which is why senators will continue to grandstand regardless of whether it advances Philippine interests.

Option 3: Multilateralization Through ASEAN

The Philippines is the 2026 ASEAN chair, which theoretically gives it a platform to build regional consensus on South China Sea issues and push for conclusion of a Code of Conduct with China.

The Case For:

- Distributes pressure across multiple states rather than bilateral confrontation

- Creates diplomatic space for compromise without unilateral concessions

- Leverages ASEAN’s collective economic weight (more comparable to China’s)

- Provides political cover for pragmatic approaches domestically

- Has historical precedent in successful ASEAN conflict management

The Case Against:

- ASEAN consensus is notoriously difficult to achieve

- China has successfully divided ASEAN on South China Sea issues before

- Cambodia, Laos, and increasingly Thailand are in China’s economic orbit

- Code of Conduct negotiations have been ongoing for over a decade with minimal progress

- Regional approach may dilute specific Philippine claims

Barok’s Assessment: This is the smart play, which means it requires patience, diplomatic skill, and a willingness to compromise on peripheral issues while protecting core interests. Whether the Marcos administration has the diplomatic capacity and political will to execute this strategy remains an open question.

The challenge is that multilateralization works best when you have time. When Chinese vessels are harassing Filipino fishermen today, “we’re building ASEAN consensus” is not a satisfying answer.

Option 4: Strategic Economic Diversification

This is the long game: reduce economic dependence on China by strengthening trade and investment ties with other partners, particularly the US, Japan, South Korea, and ASEAN neighbors.

The Strategy:

- Accelerate negotiations for stronger US-Philippines economic cooperation

- Deepen Japan-Philippines Reciprocal Access Agreement economic provisions

- Increase ASEAN economic integration

- Attract investment from companies engaged in “China+1” diversification strategies

- Develop domestic alternatives to Chinese imports where feasible

The Case For:

- Reduces China’s economic leverage over time

- Aligns with global trends (supply chain diversification)

- Attracts investment from countries seeking China alternatives

- Strengthens alliance relationships beyond just security

- Creates economic resilience against coercion

The Case Against:

- Takes years or decades to significantly shift trade patterns

- Doesn’t address immediate tensions or incidents

- May trigger Chinese retaliation during transition period (when vulnerability is highest)

- Requires sustained political will across multiple administrations

- Economically suboptimal in the short term (China is cheap and close)

Barok’s Assessment: This is the foundation of any long-term strategy that preserves both sovereignty and prosperity. The problem is that economic diversification is like exercise: everyone knows they should do it, it clearly works, and almost nobody has the discipline to sustain it.

The Philippines should have started this process seriously in 2016 when we won the Arbitral Award. That we’re only now seriously discussing it is a testament to our political class’s preference for short-term thinking.

China’s Moves: The Wolf Warrior’s Playbook

China’s strategic options are constrained by their own rhetorical commitments and need to project strength both regionally and domestically. Xi Jinping has staked significant political capital on the South China Sea claims; backing down would be seen as weakness precisely at a moment when he’s facing domestic economic challenges.

Option 1: Escalate Economic Pressure

This is the implicit threat in Ji Lingpeng’s “millions of jobs” warning.

Tactics:

- Delay import permits for Philippine agricultural goods

- Slow-roll visa approvals for Filipino workers

- Cancel or delay infrastructure projects

- Impose targeted sanctions on specific companies or sectors

- Reduce tourist arrivals

The Case For (from China’s perspective):

- Demonstrates concrete costs of confrontation

- Puts pressure on Marcos administration from affected industries

- Relatively low-cost for China (Philippine exports are not critical)

- Creates domestic political pressure in Philippines for compromise

- Consistent with China’s treatment of other countries in disputes (Australia, Lithuania)

The Case Against:

- Confirms Philippines’ case that China uses economic coercion

- Strengthens case for closer US-Philippines economic ties

- Hands propaganda victory to critics of Chinese behavior

- May trigger coordinated response from Philippines’ allies

- Risks accelerating exactly the diversification China wants to prevent

Barok’s Assessment: China is likely to pursue selective, deniable economic pressure rather than dramatic measures. Expect import permits to be mysteriously delayed, projects to face unexplained regulatory hurdles, and tourism numbers to “coincidentally” decline. This gives China leverage while maintaining plausible deniability.

The problem for China is that this strategy only works if the target is isolated. If the Philippines can quickly pivot to alternative partners, Chinese economic coercion becomes less effective and more costly to China’s reputation.

Option 2: Reciprocal Diplomatic Measures

If the Philippines declares a Chinese diplomat PNG, China will almost certainly respond in kind.

The Escalation Ladder:

- Declare Philippine diplomat(s) PNG

- Reduce diplomatic staff levels

- Downgrade diplomatic relations (Ambassador to Chargé d’Affaires)

- Impose travel bans on Philippine officials (already done for Kalayaan officials)

- Suspend diplomatic dialogue

The Case For:

- Maintains “face” by not accepting humiliation

- Signals to other countries the cost of confronting China

- Satisfies domestic nationalist sentiment

- Standard diplomatic practice (reciprocity is expected)

The Case Against:

- Further poisons relations at a time when communication is needed

- Eliminates diplomatic channels for crisis management

- Makes China look petty and vindictive internationally

- Hands victory to those arguing China is an unreliable partner

Barok’s Assessment: If the Philippines pulls the PNG trigger, China will absolutely retaliate. The only question is whether they escalate proportionally or over-respond to “teach a lesson.” Given current wolf warrior tendencies, over-response is likely.

Option 3: The Strategic Pause (Backchannel De-escalation)

This is the smart move that no one wants to talk about publicly because it looks like weakness.

The Strategy:

- Quiet diplomatic engagement through backchannels

- Identify face-saving compromises for both sides

- Separate WPS incidents from broader bilateral relationship

- Pursue “agree to disagree” framework on sovereignty while cooperating on economics

- Use Track II diplomacy (academic, business channels) to explore options

The Case For:

- Preserves relationship while conflicts simmer

- Allows both sides to avoid costly escalation

- Creates space for eventual comprehensive settlement

- Maintains economic benefits for both countries

- Consistent with China’s stated preference for bilateral negotiation

The Case Against:

- Looks like backing down from nationalist rhetoric

- Doesn’t address underlying sovereignty disputes

- May be politically unsustainable for Xi domestically

- Philippines may interpret as sign of Chinese weakness, inviting further challenges

- Requires compromises that neither side is politically positioned to offer

Barok’s Assessment: This is what will likely happen eventually, after both sides exhaust the satisfaction of public posturing. The question is how much damage gets done before we get there.

The Endgame: What Does “Winning” Look Like?

Here’s the uncomfortable truth that neither side wants to acknowledge: there is no “winning” scenario in the traditional sense. The West Philippine Sea dispute is not going to be resolved in the next five years, or probably the next fifty years. China is not going to suddenly accept the 2016 Arbitral Award. The Philippines is not going to surrender its sovereign claims.

So what does success actually look like?

For the Philippines:

- Preventing permanent Chinese presence in areas within Philippine EEZ

- Maintaining freedom of navigation and fishing for Filipino citizens

- Building alliance structures that deter Chinese aggression without triggering conflict

- Reducing economic vulnerability to Chinese pressure over time

- Maintaining international support for legal position under UNCLOS

- Avoiding armed conflict that the Philippines would lose

For China:

- Maintaining ambiguous control over disputed areas without formal annexation

- Preventing US military positioning in the Philippines from becoming permanent

- Dividing ASEAN to prevent unified regional opposition

- Demonstrating resolve to domestic and regional audiences without triggering US intervention

- Preserving economic relationships with Southeast Asian countries

- Avoiding Taiwan-like international coalition against Chinese claims

Notice something? These objectives are not mutually exclusive. There’s a possible equilibrium here, even if neither side gets everything it wants:

- China maintains de facto presence in some disputed areas without formal annexation

- Philippines maintains legal position and international support without forcing confrontation

- Both countries preserve economic relationship while managing security competition

- Incidents are managed through crisis communication channels to prevent escalation

- Long-term resolution is deferred to future generations with more wisdom (or less nationalism)

This is called a “managed rivalry”—and while it’s profoundly unsatisfying to all involved, it’s better than the alternatives (war or surrender).

The Real Strategic Question

The strategic choice facing the Philippines is not “sovereignty vs. prosperity”—that’s a false dichotomy pushed by people who benefit from Filipino defeatism. The real choice is between:

Option A: Principled strategic patience

- Assert rights consistently through legal and diplomatic channels

- Build alliances and diversify economy to reduce vulnerability

- Avoid escalation that plays to China’s strengths

- Wait for geopolitical conditions to shift in Philippines’ favor (demographics, economics, US commitment, Chinese domestic challenges)

Option B: Nationalist escalation

- Demand immediate vindication of sovereignty claims

- Pursue confrontational policies that satisfy domestic politics

- Accept economic costs as price of dignity

- Hope that international support translates to concrete change

The first option is strategic. The second is satisfying. Philippine politics has consistently chosen the second while hoping for the first option’s outcomes.

The senators grandstanding about PNG declarations are choosing satisfaction over strategy. The Chinese Embassy threatening economic consequences is choosing intimidation over persuasion. Neither approach advances their country’s actual interests, but both advance the political interests of those making the threats.

And that, dear reader, is why we’re here: because domestic politics on both sides incentivizes behavior that makes conflict more likely and resolution less achievable.

V. THE BAROK BOTTOM LINE: A CALL FOR COMITY, CLARITY, AND COMMON SENSE

So we’ve arrived at the moment of reckoning, where I’m supposed to deliver some withering verdict that leaves you both informed and entertained, enlightened and enraged. The problem is that the rational conclusion here is profoundly unsatisfying: both sides are behaving like idiots, and we’re all going to pay for it.

But since you’ve made it this far through several thousand words of legal analysis, economic deconstruction, and strategic game theory, you deserve more than fatalism. You deserve a path forward—or at least an explanation of why the obvious paths are blocked.

The Case for Comity: Why Diplomacy Matters Even When Diplomats Don’t

Let’s start with an uncomfortable acknowledgment: the Chinese Embassy’s behavior has been boorish, undiplomatic, and arguably in violation of the spirit (if not the letter) of the Vienna Convention. Ji Lingpeng’s “children playing house” comment was indefensible. The “millions of jobs” economic threat was manipulative. The public criticism of Philippine officials defending sovereignty was inappropriate.

The Senate would be entirely justified—legally, politically, and morally—in pursuing harsh reciprocal measures.

But here’s the thing about being justified: it’s not the same as being wise.

The fundamental challenge facing Philippine foreign policy is not whether we have the right to stand up to China—we absolutely do. The challenge is whether we have the capacity to stand up to China without catastrophic consequences. And if we don’t currently have that capacity, how do we build it while protecting our interests in the meantime?

This is where comity comes in—not as surrender, but as strategy.

Comity is the legal principle of reciprocal courtesy between sovereign nations. It’s what allows international relations to function even between rivals. It’s why diplomats get immunity even when they’re representing governments we despise. It’s the thin membrane of civilization that separates diplomatic notes from artillery shells.

And it’s currently being shredded by both sides in this dispute.

The Philippine Senate is treating diplomacy as performance art for the 2025 midterms. The Chinese Embassy is treating diplomacy as economic warfare by other means. Neither approach is sustainable, and both are dangerous.

Here’s what a return to comity would look like:

For the Philippines:

- Let the DFA handle diplomatic responses, not senators seeking reelection

- Use proper diplomatic channels (démarches, ambassador summons) rather than public resolutions

- Separate legitimate defense of sovereignty from grandstanding

- Accept that economic interdependence creates mutual vulnerability (which is leverage, not weakness)

- Recognize that looking tough is not the same as being effective

For China:

- Communicate through diplomatic channels rather than public threats

- Recognize that Philippine legislators have the same right to express views as Chinese officials

- Accept that the 2016 Arbitral Award will remain part of Philippine policy regardless of Chinese rejection

- Understand that economic coercion strengthens the case for diversification, not compliance

- Acknowledge that wolf warrior diplomacy is producing the opposite of its intended effect

Will either side adopt these approaches? Almost certainly not. But the failure to do so doesn’t make the recommendations wrong; it makes the current trajectory dangerous.

The Case for Clarity: Defining Red Lines and Recognizing Reality

The second requirement for a functional Philippines-China relationship is clarity about what is negotiable and what is not. The current situation is characterized by strategic ambiguity on both sides, which creates space for miscalculation.

Philippine Red Lines (What We Cannot Compromise):

- Sovereign rights within Philippine EEZ under UNCLOS and the 2016 Arbitral Award

- Freedom of navigation and fishing for Filipino citizens in Philippine waters

- Right to develop resources within Philippine maritime zones

- Alliance relationships (particularly US Mutual Defense Treaty)

- Democratic governance and free expression (including legislative criticism of foreign governments)

Chinese Red Lines (What They Cannot Compromise):

- Rejection of the 2016 Arbitral Award (accepting it would undermine all South China Sea claims)

- Historical claims to the nine-dash line (connected to domestic legitimacy narratives)

- Opposition to permanent US military presence in the Philippines

- Prevention of Taiwan-style international coalition against Chinese claims

- “Face” and regional prestige (cannot be seen as backing down to smaller neighbor)

Here’s the brutal reality: these red lines are incompatible. The Philippines cannot accept Chinese sovereignty claims without surrendering UNCLOS rights. China cannot accept the Arbitral Award without undermining its entire South China Sea position.

This means there is no comprehensive resolution available. The best-case scenario is management, not resolution—finding ways to coexist despite incompatible positions.

That management requires both sides to be clear about:

- What incidents will trigger escalation (physical harm to personnel, permanent structures in disputed areas)

- What incidents will be managed quietly (vessel encounters, verbal protests)

- What areas are potential zones of cooperation (fishing agreements, environmental protection, search and rescue)

- What areas will remain deadlocked (sovereignty claims)

The current situation has none of this clarity, which is why every incident becomes a potential crisis.

The Case for Common Sense: A Pragmatic Path Forward

So what should actually be done? If I were advising the Marcos administration (and to be clear, they have not asked and would not listen), here’s the strategy I’d propose:

Immediate Actions (Next 30 Days):

- Do NOT declare anyone persona non grata. It feels good, accomplishes nothing, and closes channels we’ll need later.

- Have the DFA issue a formal diplomatic note (démarche) to the Chinese Embassy expressing concern about the tone and content of recent statements, particularly the economic threat, as inconsistent with diplomatic norms.

- Privately communicate to China through backchannels that:

- The Philippines will continue to defend its UNCLOS rights

- Economic threats will accelerate diversification, not compliance

- The door remains open for productive dialogue on areas of mutual interest

- Continued public statements of the kind Ji issued will make diplomatic normalization politically impossible

- Publicly emphasize continuity of policy: The Philippines is not escalating; we are defending long-standing positions. This is about China’s behavior, not about Philippine aggression.

Short-Term Strategy (Next 6-12 Months):

- Use ASEAN chairmanship to build regional consensus on freedom of navigation and peaceful dispute resolution, without requiring ASEAN endorsement of specific Philippine claims (which won’t happen).

- Accelerate economic diversification:

- Fast-track Japan-Philippines economic cooperation agreements

- Expand US-Philippines trade beyond security goods

- Strengthen ASEAN economic integration

- Attract investment from companies pursuing “China+1” strategies

- Strengthen maritime domain awareness through alliance support:

- US intelligence sharing

- Japanese maritime patrol cooperation

- Australian surveillance support

- This increases costs of Chinese misbehavior without Philippine escalation

- Pursue selective cooperation with China in non-contentious areas:

- Agricultural trade (where Philippines benefits)

- People-to-people exchanges

- Environmental cooperation

- This maintains relationship ballast while managing security competition

Long-Term Strategy (Next 5-10 Years):

- Build economic resilience that reduces vulnerability to Chinese pressure:

- Diversify export markets

- Develop domestic manufacturing

- Strengthen regional supply chains

- Position Philippines as alternative to China for certain industries

- Maintain legal high ground through consistent UNCLOS compliance:

- Document all incidents meticulously

- Bring recurring issues to international attention

- Build international consensus for legal position

- This sets conditions for eventual favorable resolution

- Strengthen alliance deterrence without provocation:

- Maintain US defense treaty commitments

- Deepen Japan security cooperation

- Participate in multilateral exercises

- This raises costs of Chinese aggression without threatening China

- Prepare for long-term management of unresolved disputes:

- Build institutional capacity for crisis communication

- Develop protocols for incident management

- Create economic shock absorbers for potential Chinese retaliation

- Train diplomatic corps for sustained rivalry management

What Success Actually Looks Like

If this strategy is executed successfully, here’s what we should see in five years:

- No Chinese permanent structures within Philippine EEZ (success = maintaining status quo, not reversing existing Chinese positions)

- Reduced frequency and intensity of harassment incidents due to better deterrence

- Economic growth continues despite managed tensions with China

- Strengthened alliance relationships provide security without triggering Chinese overreaction

- International support for Philippine legal position remains solid

- ASEAN progress on Code of Conduct, even if not completed

- No armed conflict between Philippines and China

Notice what’s NOT on that list:

- China accepting the Arbitral Award

- Chinese withdrawal from disputed features

- Resolution of sovereignty claims

- End of tensions

Those outcomes are not achievable in the next decade. Pretending they are leads to strategies that fail and then get abandoned, leaving us worse off.

The Final, Uncomfortable Truth

The Philippines is a small country in a strategic location dealing with a large, powerful, and aggressive neighbor. We did not choose this situation. We did not create these tensions. We are not the aggressor.

But we are the weaker party, which means we need to be smarter than our adversary, not just more righteous.

Righteousness without power is called martyrdom. The Philippines has been martyred enough in its history. What we need now is strategic patience combined with systematic capability building.

That means:

- Sometimes swallowing insults from boorish diplomats because escalation serves their interests more than ours

- Sometimes accepting economic discomfort as the price of sovereignty

- Sometimes looking “weak” to domestic audiences because the alternative is being actually weak in ways that matter

- Always remembering that the goal is not to feel good about our position but to improve our position

The senators grandstanding about persona non grata declarations are not helping. They’re making themselves feel important while making the country more vulnerable. Their resolutions won’t bring back Scarborough Shoal. They won’t stop the next harassment incident. They won’t make China respect Philippine sovereignty.

What they will do is give China an excuse to retaliate, poison diplomatic channels we’ll need during the next crisis, and make the difficult work of actual diplomacy even harder.

And the Chinese Embassy’s behavior? Equally counterproductive. Every economic threat strengthens the case for diversification. Every insulting comment builds political support for closer US alliance ties. Every wolf warrior outburst confirms that China cannot be trusted to respect sovereignty or norms.

Both sides are trapped in a cycle of performative escalation that serves domestic political interests while undermining national strategic interests.

The Call to Action: Choose Strategy Over Satisfaction

So here’s my call—not to the Senate (they won’t listen), not to the Chinese Embassy (they can’t listen), but to the Filipino people who will ultimately bear the costs of this diplomatic disaster:

Demand strategic competence from your leaders.

Ask not whether they’re standing up to China, but whether their actions are advancing Philippine interests. Ask not whether they’re protecting dignity, but whether they’re protecting fishermen. Ask not whether they’re tough, but whether they’re effective.

Because here’s the thing: the West Philippine Sea dispute is not a movie where the hero gets vindication in the third act. It’s a multi-generational challenge that will outlast current leaders and require sustained strategic effort across multiple administrations.

We need leaders who understand that diplomacy is not weakness, that economic interdependence is not surrender, that sometimes the best response to provocation is strategic silence, and that the goal is not to win the news cycle but to position the Philippines for long-term success.

We need a foreign policy that is principled but pragmatic, firm but flexible, assertive but not suicidal.

We need to remember that our sovereignty is not just about where our flag flies, but whether our people prosper, whether our fisher folk can feed their families, whether our economy can withstand pressure, whether our alliances will hold when tested.

And we need to accept that the satisfying response is usually not the smart response—and that our leaders are paid to be smart, not satisfying.

The Barok Bottom Line

Senate President Sotto, you have every right to be annoyed. You have every legal justification for a PNG declaration. You have the moral high ground.

But you also have a responsibility to the Filipino people that goes beyond your political brand. And that responsibility requires you to ask whether your actions are making the situation better or worse.

Chinese Embassy, you have legitimate interests to defend. You have a right to communicate your position. You have reasons to be frustrated with Philippine domestic politics.

But you also represent a country that claims to respect sovereignty and pursue “win-win cooperation.” Those claims are incompatible with economic threats and public insults. You are teaching Filipinos that China cannot be trusted—and that lesson will shape Philippine foreign policy for generations.

To both sides: The West Philippine Sea dispute will outlast all of us. The question is whether we leave it better or worse than we found it. Whether we create conditions for eventual resolution or permanent hostility. Whether we manage competition rationally or let it spiral into conflict.

Right now, both sides are choosing the path that leads to conflict. Not immediately. Not dramatically. But inexorably.

There is another path—difficult, unglamorous, requiring patience and wisdom that short-term politics rarely rewards. But it’s the only path that serves the actual interests of the Filipino people and the long-term interests of regional peace.

The question is whether anyone has the courage to take it.

POSTSCRIPT: A Note on Irony

As I finish writing this, I’m struck by the profound irony that Leila de Lima—a woman imprisoned for years on charges widely viewed as political persecution, a woman whose own record on respecting legal process and civil liberties is checkered at best—is now lecturing Chinese diplomats about the abuse of immunity and the importance of free speech.

There is something deliciously absurd about a former official who weaponized the justice system against political opponents now positioning herself as a champion of democratic norms. The universe has a sense of humor.

But even broken clocks are right twice a day. And even Leila de Lima can stumble into a correct position occasionally, even if her path there required political persecution, imprisonment, and eventual martyrdom.

Perhaps that’s fitting. Perhaps the West Philippine Sea dispute can only be resolved by similarly unlikely transformations: China learning to respect international law after decades of rejecting it. The Philippines learning strategic patience after centuries of being victimized. Politicians learning to prioritize national interest over political advantage.

I’m not holding my breath. But stranger things have happened.

After all, we elected a former dictator’s son as president. Anything is possible.

Louis “Barok” C. Biraogo is the proprietor of Kweba ni Barok and a recovering optimist about Philippine politics. He can be reached at barok@kweba.ph, though he rarely responds because he’s usually rage-reading diplomatic cables.

The views expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not represent any organization, institution, or government agency—which is fortunate, because no organization with any sense would claim them.

Key Citations

A. Legal & Official Sources

- “1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines.” Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, http://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/constitutions/the-1987-constitution-of-the-republic-of-the-philippines/.

- Philippine Maritime Zones Act. Republic Act No. 12064, Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, 8 Nov. 2024, http://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/downloads/2024/11nov/20241108-RA-12064-RRD.pdf.

- The Philippines v. China. PCA Case No. 2013-19, Permanent Court of Arbitration, 12 July 2016, pcacases.com/web/sendAttach/2086.

- “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.” United Nations, 10 Dec. 1982, http://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf.

- “Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations.” United Nations, 18 Apr. 1961, legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/9_1_1961.pdf.

- “Senate Resolution No. 256.” Senate of the Philippines, 9 Feb. 2026.

B. News Reports

Leave a comment