How the Same Government That Speed-Delivered the Former President Now Wants a Local Judge’s Blessing Before Touching Senators

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — February 18, 2026

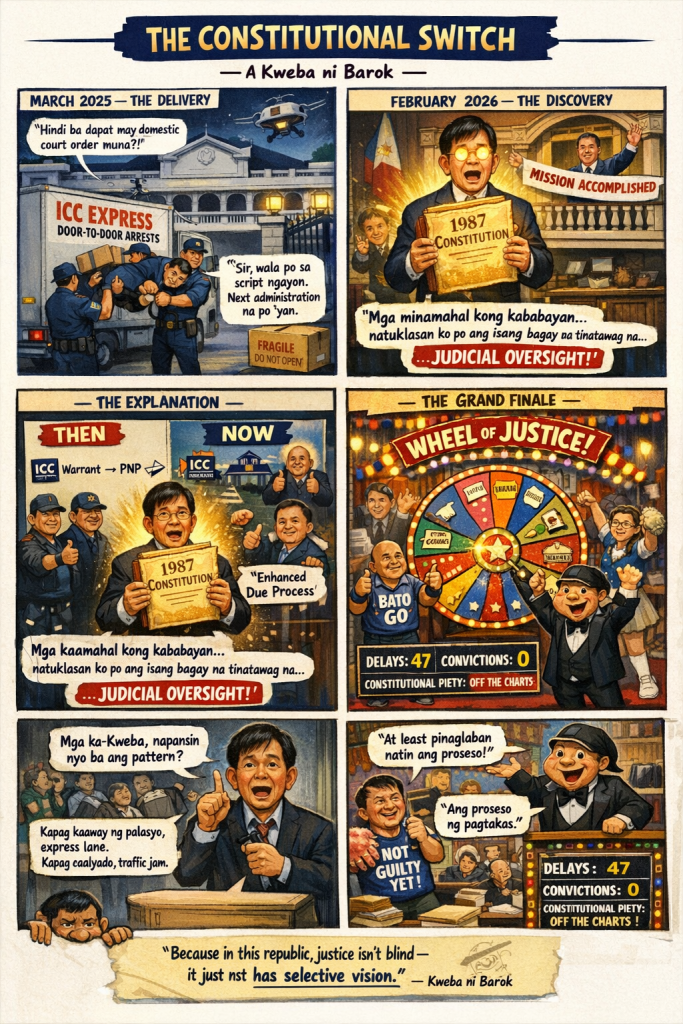

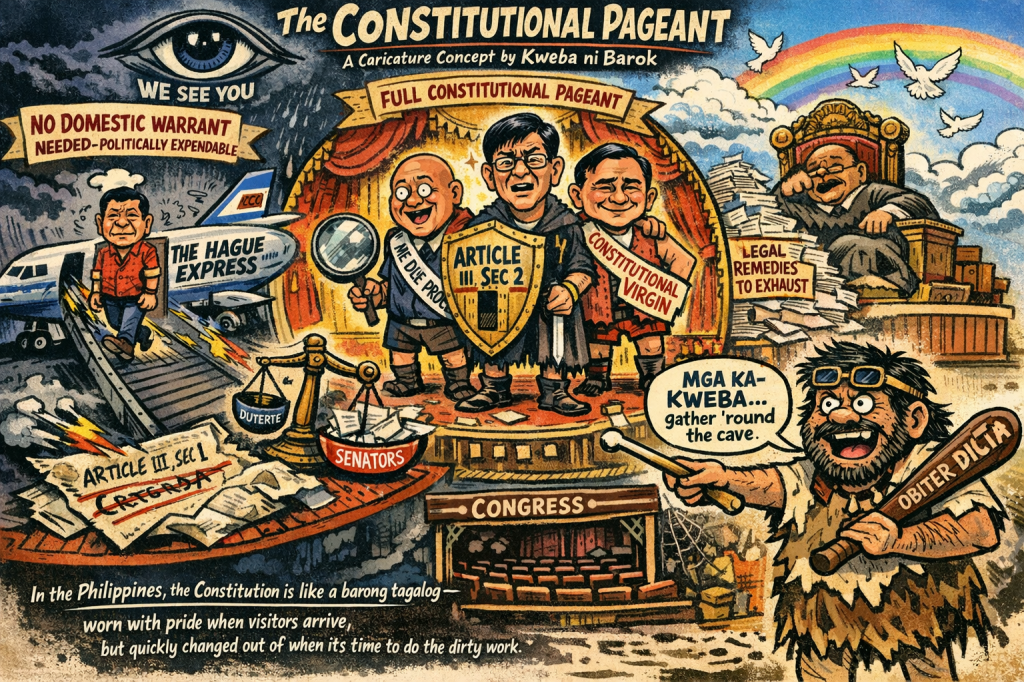

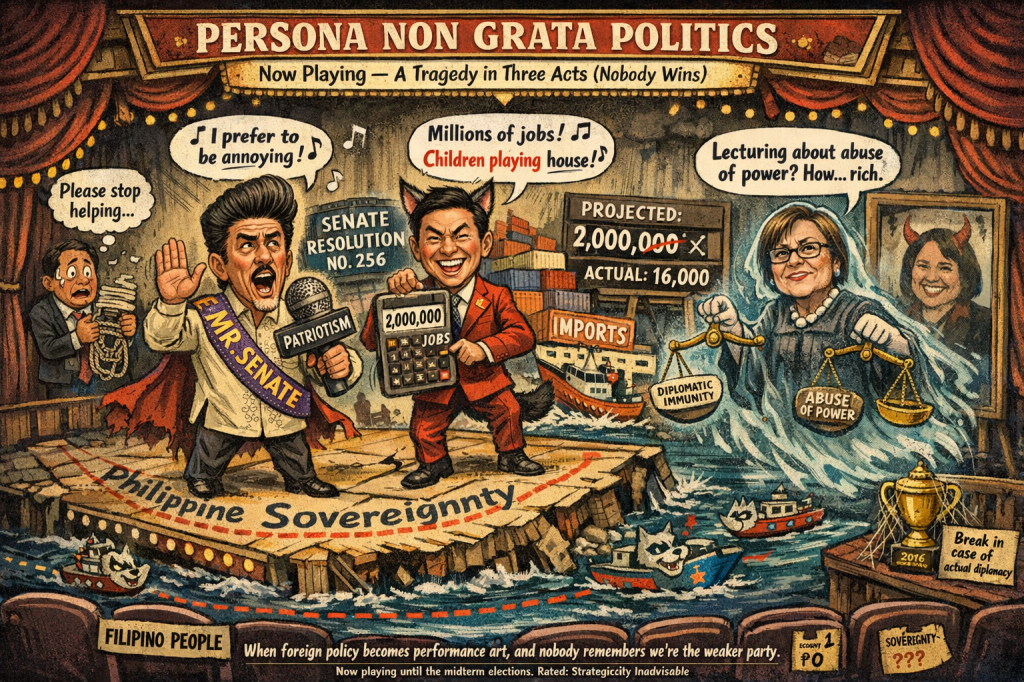

MGA ka-kweba, dear masochists who still bother reading Philippine political news in 2026, gather ’round the cave. Another day, another senator discovering the sacred inviolability of the 1987 Constitution—selectively, of course—right when his colleagues’ necks are on the International Criminal Court (ICC)’s chopping block. Senate President Pro Tempore Panfilo “Ping” Lacson, the man who once positioned himself as the incorruptible Mr. Clean, has suddenly become the most passionate defender of Article III, Section 2 you’ll ever meet. And all because Senators Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa and Bong Go have been publicly named as alleged co-perpetrators in the ICC’s freshly unredacted Document Containing Charges against Rodrigo Roa Duterte.

Lacson insists—oh so solemnly—that his demand for a “corresponding domestic court order” before any ICC arrest warrant can be executed is about protecting “our country’s legal processes,” not shielding his fellow senators. How noble. How convenient. How utterly, transparently laughable.

Let’s dissect this circus, shall we? Slowly, deliberately, with the scalpel of a jaded lawyer who’s seen every trick in the book—and watched the book get burned for political expediency.

The Core Argument: Principled Stand or Smoke and Mirrors?

Lacson’s entire edifice rests on Article III, Section 2 of the 1987 Constitution: no warrant of arrest shall issue except upon probable cause determined personally by a judge after examination under oath. Translation: only a Philippine judge can green-light an arrest inside Philippine territory. An ICC warrant, in Ping’s world, is just a fancy foreign piece of paper until a local court stamps it “approved.”

On its face, it’s not a crazy argument. The provision is absolute, self-executing, and has been interpreted to require Philippine judicial oversight for any deprivation of liberty on our soil. Extradition jurisprudence—Government of the United States v. Purganan (G.R. No. 148571, 2002)—reinforces this: foreign requests don’t automatically bind our cops.

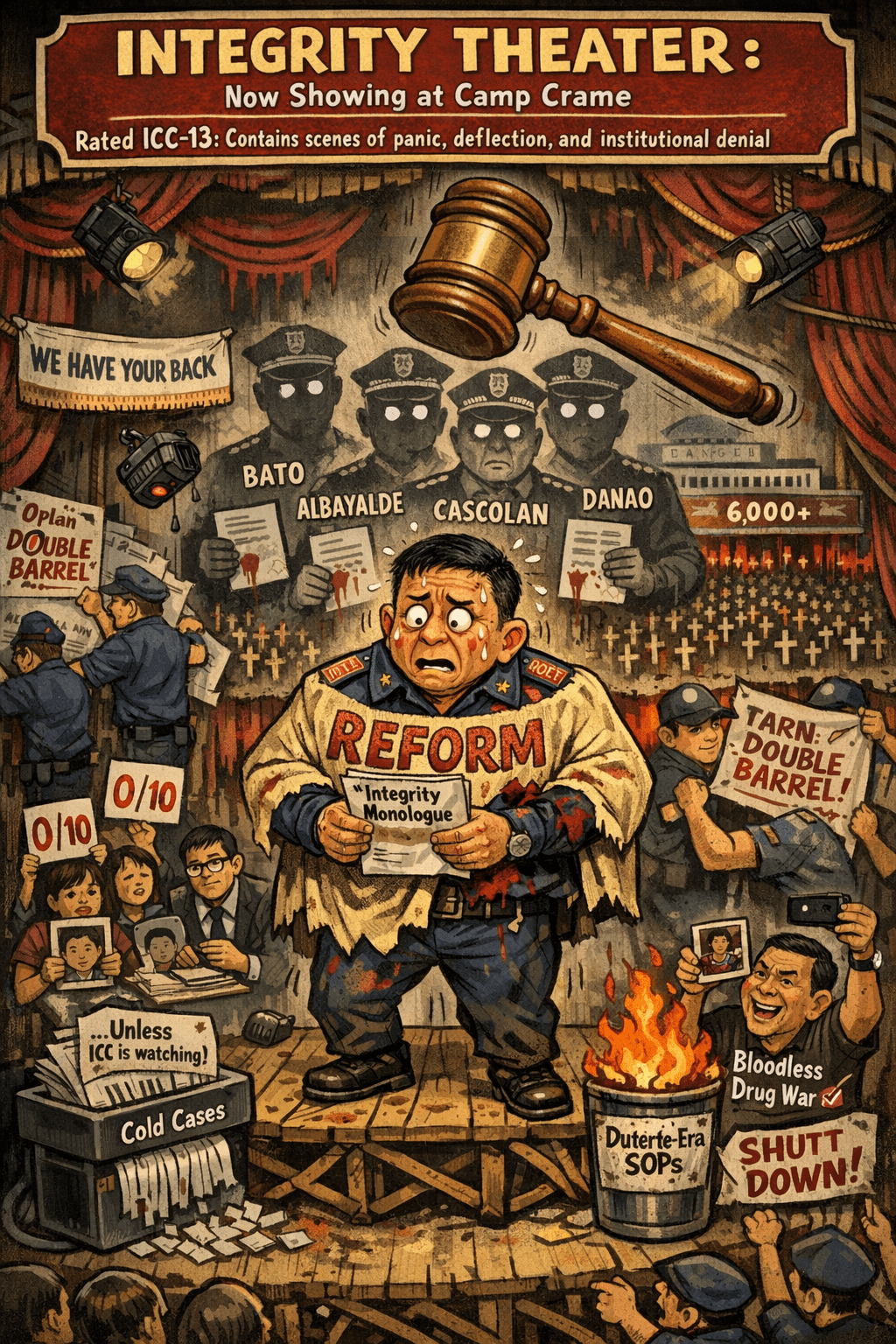

But let’s not pretend this is pure constitutional piety. The timing is exquisite. Duterte himself was arrested by the Philippine National Police (PNP) on an ICC warrant (via Interpol diffusion) in March 2025 and whisked off to The Hague without any prior “corresponding domestic court order.” No one in the Senate—including the suddenly fastidious Lacson—screamed bloody murder then. Why? Because it was Duterte alone, the big fish, and the Marcos administration wanted him gone. Now that the net has widened to include loyal lieutenants Bato and Bong Go, suddenly the Constitution is sacrosanct again.

This isn’t principle. This is selective sovereignty—a classic Philippine political reflex: international law is binding when it’s convenient, meaningless when it threatens the club.

The Legal Framework: A House Built on Sand and Hypocrisy

Let’s go deeper, because Lacson wants us to take his constitutional argument seriously.

Article III, Section 2 is indeed ironclad. But it doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Article II, Section 2—the incorporation clause—makes generally accepted principles of international law (Rome Statute). Cooperation with international tribunals for crimes against humanity? That’s a generally accepted principle. Republic Act No. 9851 (the Philippine Act on Crimes Against International Humanitarian Law) explicitly mandates surrender and extradition to international tribunals (Sections 7 and 17). No implementing rules needed, no prior domestic warrant required.

Then there’s Article 127(2) of the Rome Statute: withdrawal doesn’t discharge obligations for crimes committed while we were members. And the Supreme Court (SC)’s obiter in Pangilinan v. Cayetano (G.R. No. 238875, 2021) made it clear: the Philippines “shall not be discharged from any criminal proceedings” arising from pre-withdrawal acts.

Most damning of all: the Duterte precedent. Rodrigo Duterte was arrested and surrendered without the elaborate domestic court ritual Lacson now demands. The SC entertained habeas petitions but never blocked the transfer. If that process was constitutional for the former President, why is it suddenly unconstitutional for his alleged co-perpetrators?

Lacson’s reading isn’t just selective—it’s an anachronism. The statutory framework (RA 9851) and recent practice render his position a convenient relic.

The Duterte Precedent Paradox: Why Was It Good Enough for Digong?

Let’s linger here, because the hypocrisy is delicious.

In March 2025, the PNP arrested Duterte on an ICC warrant. No local judge signed off beforehand. No “corresponding domestic court order.” The Marcos administration cooperated smoothly, Interpol was involved, and off he went to The Hague. The Senate didn’t convene emergency sessions to defend constitutional due process. Lacson didn’t tweet threads about judicial sovereignty.

Fast-forward to February 2026: Bato and Bong Go are named. Suddenly, the Constitution roars to life. Suddenly, our local courts must be respected. Suddenly, everyone gets to exhaust all legal remedies.

Why the difference? Because Duterte was expendable to the current powers-that-be. His lieutenants still have seats, votes, and loyalty networks. This isn’t about law. This is about political survival.

The Statutory Vacuum: Where Sovereignty Goes to Hide

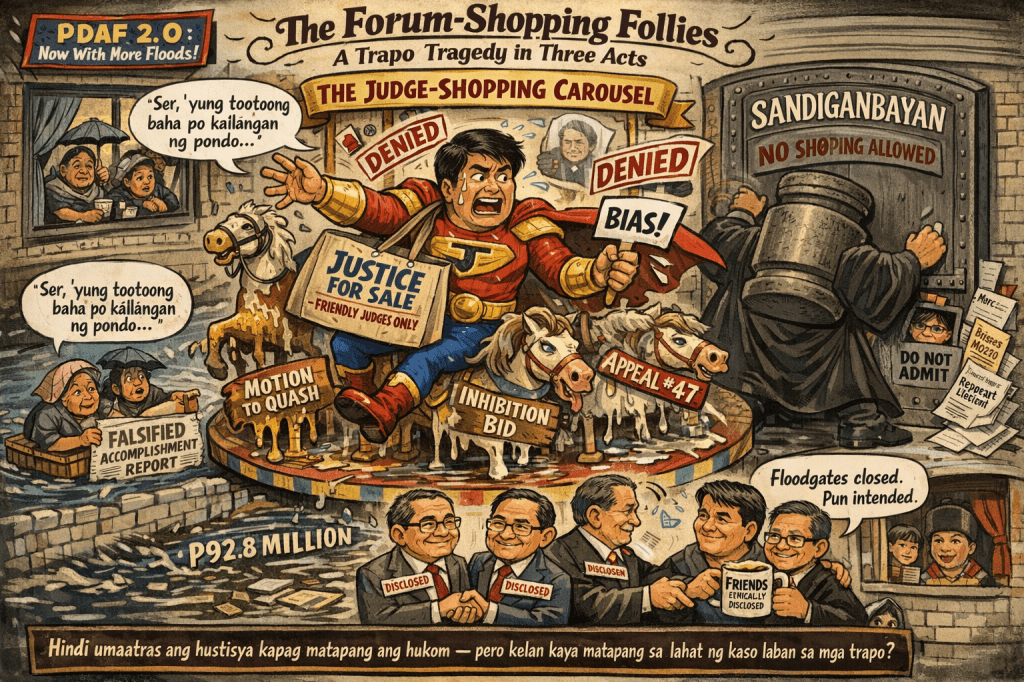

The real scandal isn’t Lacson’s position—it’s that we’re even having this debate. The Philippines has no clear enabling law for ICC cooperation post-withdrawal. Extradition laws (Presidential Decree No. 1069) are designed for states, not international tribunals. RA 9851 gestures toward cooperation but leaves the mechanics vague. That vacuum allows every senator with a guilty conscience to wrap himself in the Constitution and play patriot.

This isn’t sovereignty. It’s a loophole big enough to drive a presidential convoy through.

Motivations and Endgames

- Lacson: trying to salvage his “Mr. Clean” brand while not completely alienating the Duterte bloc. Institutional defense of the Senate is part of it—he doesn’t want a precedent where senators can be plucked off the floor by foreign warrants.

- Dela Rosa and Go: pure self-preservation.

- Marcos administration: quietly delighted. Cooperating with the ICC burnishes their international image and keeps the Duterte faction weak.

- The ICC: just doing its job, undeterred by Manila’s theatrical sovereignty tantrums.

Likely resolution? If warrants issue, the administration will probably follow the Duterte playbook: arrest, brief judicial review (post-arrest, per Article 59 of the Rome Statute), and surrender. The SC will be petitioned, will take its sweet time, and will likely uphold the RA 9851 framework. Lacson gets to posture. The senators get a brief delay. Justice, such as it is, grinds forward.

Final Demands from the Cave

Enough games. Here’s what must happen:

- Supreme Court, get off the bench. Issue an immediate, binding interpretation of how Article III, Section 2 interacts with RA 9851 and our surviving Rome Statute obligations. End this farce of “contrasting legal opinions” that exist only to buy time for the powerful.

- Congress, do your damn job. Pass clear legislation on cooperation with international tribunals. Spell out the procedures, the safeguards, the review mechanisms. Stop leaving solemn treaty obligations to be kicked around like a political football every time a senator’s name appears on a charge sheet.

- Executive branch, choose diplomacy over grandstanding. Navigate these obligations with maturity instead of alternating between cooperation when it’s politically convenient and defiance when it scores domestic points. The country’s reputation isn’t a bargaining chip for the next election cycle.

Until then, we’ll keep watching the same tired play: politicians discovering the Constitution only when it serves as a shield, not when it demands accountability.

Welcome to the Philippines—where due process is sacred, until it isn’t.

— Barok

Because in this republic, justice is just another word for “timing.”

Yours in perpetual disbelief,

Kweba ni Barok

Key Citations

A. Legal & Official Sources

- The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, http://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/constitutions/1987-constitution/.

- Republic Act No. 9851 (Philippine Act on Crimes Against International Humanitarian Law, Genocide, and Other Crimes Against Humanity). 11 Dec. 2009, lawphil.net/statutes/repacts/ra2009/ra_9851_2009.html.

- Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. International Criminal Court, http://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/RS-Eng.pdf.

- Government of the United States v. Purganan. G.R. No. 148571, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 24 Sept. 2002, lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2002/sep2002/gr_148571_2002.html.

- Pangilinan v. Cayetano. G.R. No. 238875, Supreme Court of the Philippines, 16 Mar. 2021, lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2021/mar2021/gr_238875_2021.html.

- Presidential Decree No. 1069 (Philippine Extradition Law). 13 Jan. 1977, lawphil.net/statutes/presdecs/pd1977/pd_1069_1977.html.

B. News Reports

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

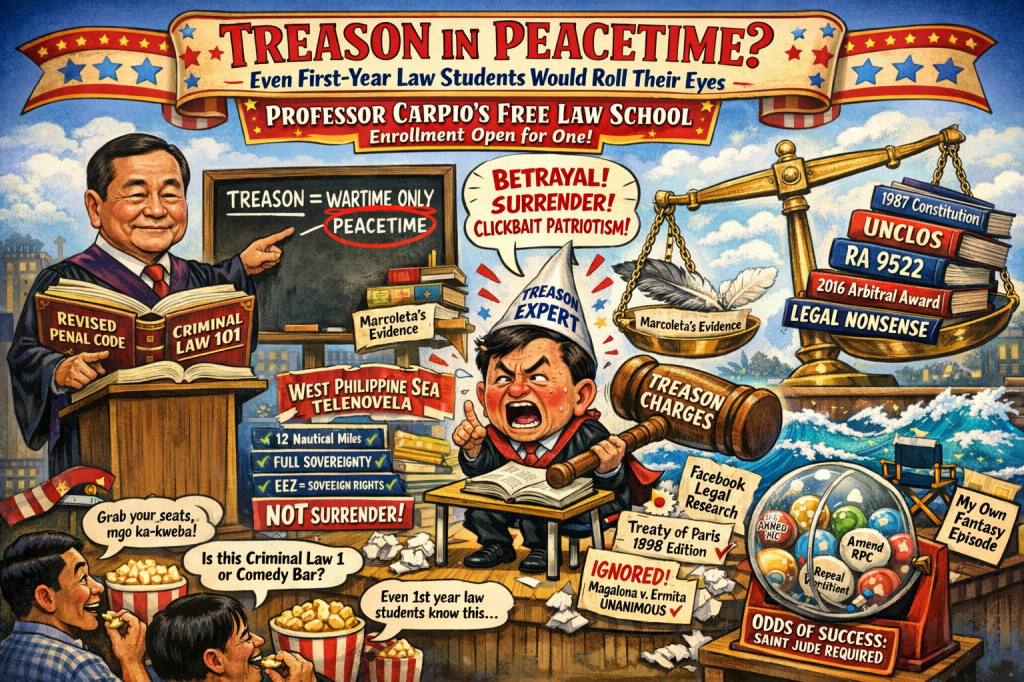

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a comment