By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo – February 2, 2025

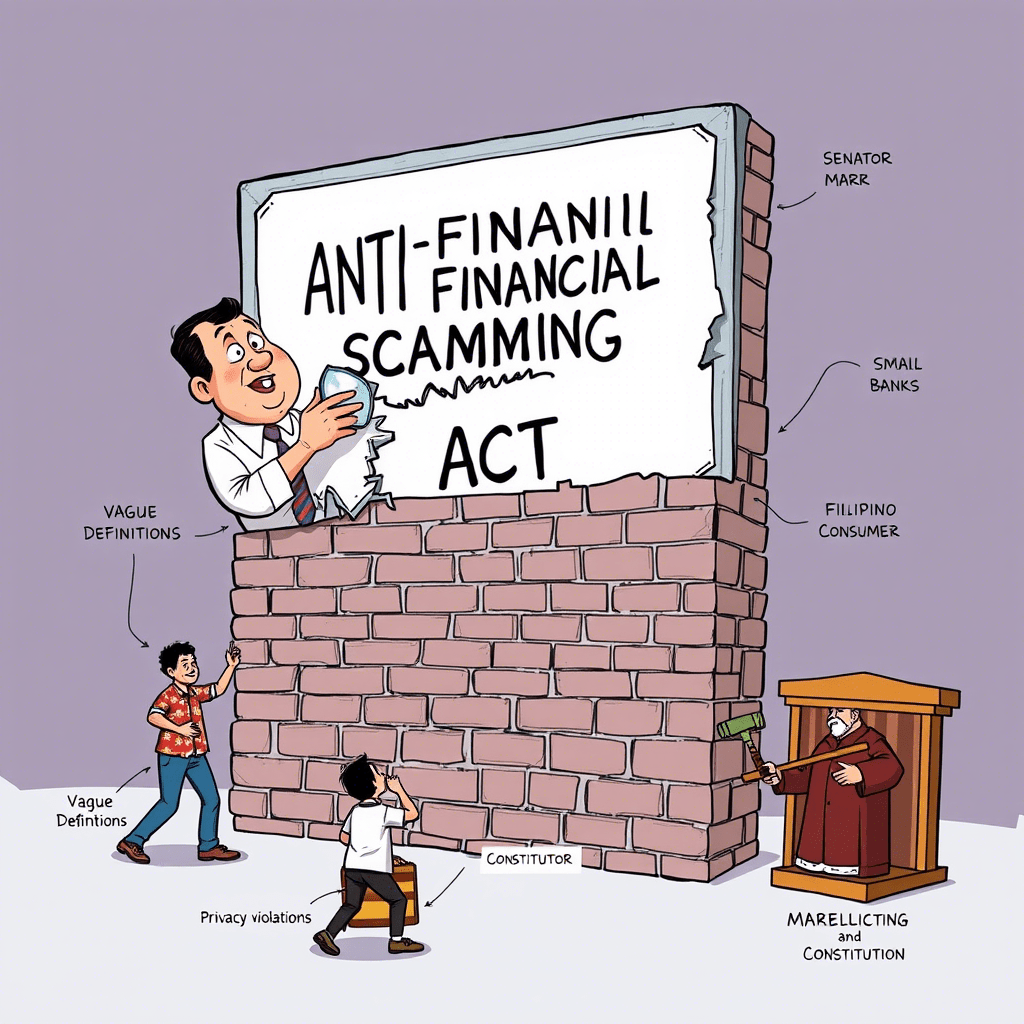

THE proposed Anti-Financial Scamming Act, introduced by Senator Mark Villar, aims to combat the rising threat of online financial fraud in the Philippines. While the bill is a commendable effort to modernize the legal framework, it raises significant legal and social concerns that must be addressed to ensure its effectiveness and constitutionality.

Closing the Gaps: How the Bill Addresses Modern Cybercrime Challenges

- Updating Existing Laws: The bill addresses gaps in the Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA) and the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012, which do not comprehensively cover modern scams like phishing, smishing, and money muling. The bill’s targeted approach aligns with the need for adaptive legislation, as emphasized in Disini v. Secretary of Justice (2014).

- Strengthening Law Enforcement: The bill grants the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) broader authority to investigate suspicious accounts and freeze transactions, bypassing bank secrecy laws in certain cases. This aligns with the state’s interest in protecting public welfare, as recognized in Gamboa v. Teves (2011).

- Criminalizing New Forms of Fraud: The bill explicitly criminalizes money muling and social engineering, which are not adequately addressed under existing laws. This is consistent with the Supreme Court’s call for laws to keep pace with technological advancements, as seen in People v. Sy Chua (2013).

- Enhancing Consumer Protection: The bill mandates financial institutions to adopt multi-factor authentication (MFA) and advanced fraud management systems (FMS), reinforcing their duty to safeguard customer funds, as established in Spouses Santos v. BPI Family Savings Bank (2015).

- Public Interest and Police Power: The bill serves the public interest by protecting citizens from financial fraud and enhancing national cybersecurity, falling within the state’s police power mandate under the Constitution.

Overreach and Ambiguity: Legal Critiques of the Anti-Financial Scamming Act

- Violation of Bank Secrecy Laws: Granting the BSP authority to bypass bank secrecy laws could infringe on the constitutional right to privacy, as protected under Republic Act No. 1405 and the 1987 Constitution. The Supreme Court in Chavez v. Public Estates Authority (2003) emphasized the importance of safeguarding individual rights, even in the pursuit of public interest.

- Overbroad or Vague Definitions: The bill’s definitions of terms like “phishing” and “money muling” may be overly broad or vague, potentially leading to arbitrary enforcement and violating due process. The Void-for-Vagueness Doctrine and Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution require clear and precise definitions to avoid unjust prosecutions.

- Overreach of BSP Authority: Expanding the BSP’s investigative powers may blur the lines between regulatory and law enforcement functions, undermining the separation of powers. The Separation of Powers Doctrine and Republic Act No. 10175 assign primary responsibility for cybercrime investigations to the NBI and PNP, creating potential jurisdictional conflicts.

- Disproportionate Penalties: The bill’s penalties may be disproportionate to the harm caused, violating the principle of proportionality in criminal law. The Revised Penal Code and Republic Act No. 10951 require penalties to be proportionate to the gravity of the offense.

- Burden on Financial Institutions: Mandating MFA and FMS could impose undue burdens on smaller banks and fintech companies, potentially violating the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution. The Philippine Identification System Act recognizes the need for phased implementation and reasonable accommodations.

From Weakness to Strength: Proposals for a More Robust Legislation

- Clarify Definitions: Provide precise definitions for terms like “phishing” and “money muling” to avoid ambiguity and ensure consistent enforcement.

- Incorporate Safeguards: Require judicial oversight for the BSP’s investigative powers and mandate transparency mechanisms to protect privacy rights.

- Limit BSP Authority: Clearly delineate the BSP’s role as a regulator and establish coordination protocols with law enforcement agencies to prevent overreach.

- Ensure Proportional Penalties: Introduce tiered penalties based on the severity of the offense and allow courts to consider mitigating factors.

- Provide Accommodations for Smaller Institutions: Allow phased implementation of MFA and FMS requirements and offer technical and financial assistance to smaller institutions.

- Enhance Consumer Education: Allocate funds for public awareness campaigns and mandate financial institutions to provide clear warnings about potential risks.

- Strengthen Accountability: Create an independent oversight body to monitor the BSP’s use of expanded powers and protect whistleblowers.

- Align with International Standards: Incorporate elements of the FATF’s anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing standards to enhance global cooperation.

- Leverage Technology: Encourage the adoption of AI-driven fraud detection systems and establish a centralized fraud database.

- Include Incentives for Compliance: Offer tax breaks or subsidies to institutions that invest in advanced fraud prevention technologies.

Conclusion

The Anti-Financial Scamming Act is a crucial shield against online fraud, but even the strongest laws crack under weak foundations. Without addressing its vague provisions, privacy risks, and disproportionate penalties, the bill may become less of a safeguard and more of a liability. If legislators refine its framework with precision and foresight, they can forge a law that truly protects Filipinos—one that defends both financial security and individual freedoms in the digital age.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

- $2 Trillion by 2050? Manila’s Economic Fantasy Flimsier Than a Taho Cup

- $26 Short of Glory: The Philippines’ Economic Hunger Games Flop

Leave a comment