By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — March 4, 2025

HOLD onto your gavels—this is one for the legal history books. In a move that’s as bold as it is baffling, newly minted COA Commissioner Douglas Michael N. Mallillin stormed into the Supreme Court on February 25, 2025, to defend PhilHealth’s controversial fund transfer. With less than a month on the job, his audacious appearance has sparked a firestorm of debate over ethics, independence, and the very integrity of constitutional oversight.

The problem? His day job is auditing the very entity he’s now cheerleading for, and he didn’t even bother with the procedural nicety of a court leave. The Sin Tax Coalition’s Cielo Magno-Gatmaytan called it a “blatant disregard for COA’s autonomy,” and she’s not wrong.

This isn’t just a faux pas—it’s a constitutional and statutory trainwreck begging for a reckoning. Let’s dissect this mess with the precision of a Supreme Court en banc ruling and the bite of a legal eagle’s exposé.

Constitutional Violations: Shredding Article IX-A, Section 2

The 1987 Constitution doesn’t mince words about constitutional commissions like COA: they’re independent, period. Article IX-A, Section 2 is crystal clear—commissioners can’t hold “any other office or employment” during their term, a safeguard to keep them from moonlighting in ways that compromise their impartiality. Mallillin’s Supreme Court cameo isn’t just a toe over the line; it’s a full-on sprint into forbidden territory.

- The Violation: By appearing as an advocate for PhilHealth—a government-owned corporation under COA’s audit jurisdiction—Mallillin effectively took on a dual role: auditor and defender. This isn’t mere “appearance of impropriety”; it’s a screaming conflict of interest that undermines COA’s constitutionally mandated independence under Article IX-D.

- The Fallout: COA’s supposed to be a fiscal watchdog, not a lapdog for the Department of Finance (DOF). Mallillin’s stunt risks turning an independent commission into an administration mouthpiece, echoing the Marcos-era playbook of stacking institutions with loyalists. The Supreme Court’s own Justice Amy Lazaro-Javier caught the whiff of bias and excused him mid-argument—rarely does a justice move that fast outside of a fire drill.

Statutory Violations: A Smorgasbord of Legal No-Nos

Mallillin didn’t just trip over the Constitution—he plowed through a gauntlet of statutes and rules like a bull in a china shop. Let’s tally the damage.

- Republic Act No. 6713 (Code of Conduct): Section 7(b)(2) forbids public officials from engaging in private practice or activities conflicting with their duties. Arguing for PhilHealth—a COA auditee—while wearing his commissioner hat isn’t just a breach; it’s a neon-lit billboard of ethical failure.

- Republic Act No. 3019 (Anti-Graft Act): Section 3(b) nails public officers who intervene in official matters where they have a personal stake. If Mallillin’s actions were swayed by DOF pressure or political favor (hello, fresh Marcos Jr. appointee!), this could escalate from dumb to corrupt. Bad faith isn’t proven yet, but the optics are grim.

- COA Internal Rules: COA Circular No. 2012-001 demands commissioners maintain impartiality in audits. Defending PhilHealth’s fund transfer—contrary to years of COA findings—torpedoes that duty faster than you can say “audit report.”

- Supreme Court Procedural Rules: Rule 65 proceedings (like this PhilHealth case) require prior leave for non-parties to appear. Mallillin waltzed in uninvited, courtesy of the OGCC, turning a solemn oral argument into a procedural circus. The Court’s patience isn’t infinite—expect a reprimand.

Legal Consequences: The Hammer’s Coming Down

Mallillin’s not walking away from this unscathed. Here’s the laundry list of penalties he’s flirting with:

Administrative Liability:

- RA 6713 Breach: Section 11 prescribes suspension (up to 6 months) or removal, plus fines up to six months’ salary. Removal’s on the table given the gravity—COA’s credibility is bleeding out.

- Conduct Unbecoming (CSC Rules): A commissioner acting as a rogue advocate could face suspension (1-6 months) or dismissal for “gross misconduct.” The Ombudsman’s got jurisdiction here, and they don’t mess around.

Criminal Liability:

- RA 3019 Violation: If partiality or bad faith sticks, Section 9 dishes out 6-15 years in prison, perpetual disqualification from office, and fines up to thrice the ill-gotten gains (if any). No smoking gun yet, but intent’s under the microscope.

- Unauthorized Practice (If Applicable): If Mallillin’s not a lawyer—or lacked COA clearance—Article 209 of the Revised Penal Code could slap him with arresto mayor (1-6 months) and fines.

Civil Liability:

No direct damages yet, but if petitioners (like Magno-Gatmaytan) prove financial harm from his advocacy—like skewed PhilHealth audits—they could sue for restitution. Long shot, but not impossible.

Disbarment Analysis: A Lawyer’s Nightmare

Assuming Mallillin’s a member of the bar (common for COA appointees), his law license is dangling by a thread. Rule 138, Section 27 of the Rules of Court lists “grossly immoral conduct” and “violation of the lawyer’s oath” as disbarment triggers. Let’s break it down:

- Canon 1 (Integrity): Lawyers must uphold the Constitution and legal processes. Mallillin’s constitutional overreach—subverting COA’s independence—mocks this duty.

- Canon 6 (Public Service): Public officials who are lawyers must avoid conflicts that erode trust. Arguing for an auditee while auditing it isn’t just a conflict—it’s a betrayal of public office.

- Jurisprudence: A.C. No. 7446 (Re: Misconduct of Atty. Villanueva) saw disbarment for gross misconduct undermining public trust. Mallillin’s actions mirror this—willful, public, and corrosive. The Integrated Bar of the Philippines (IBP) could launch a probe if a complaint lands, and the Supreme Court’s primed to act given its mid-hearing rebuke.

Comparative Analysis: Lessons from the Past

The Supreme Court’s seen this movie before—constitutional officers stepping out of line isn’t new. Three precedents paint the picture:

- Funa v. Villar (G.R. No. 192791, 2013): The Court axed COA Chairman Villar’s dual role as a trustee of a government firm, citing Article IX-A, Section 2. Mallillin’s advocacy isn’t a formal “office,” but the conflict’s eerily similar—independence took a hit, and the Court didn’t flinch.

- Civil Liberties Union v. Executive Secretary (G.R. No. 83896, 1991): Cabinet members were barred from other posts to preserve checks and balances. Mallillin’s not Cabinet, but the principle holds: dual roles muddy constitutional waters.

- Aguinaldo v. COMELEC (G.R. No. 132890, 1999): A COMELEC official’s partisan act got him bounced for breaching independence. Mallillin’s PhilHealth defense isn’t partisan per se, but it’s cozying up to the executive—a red flag.

These cases scream one thing: the Court guards constitutional commissions like a hawk. Mallillin’s not rewriting history; he’s just the latest to test it.

Recommendations: Fixing the Mess Before It Festers

This isn’t a “tsk-tsk and move on” moment—it’s a clarion call for action. Here’s the playbook:

Supreme Court:

- Issue a Ruling: In Pimentel et al. v. House, clarify that COA officials can’t advocate for auditees—ever. Cite Article IX-A and precedents like Funa.

- Sanction Mallillin: A formal reprimand for procedural breach (no leave) sets the tone. Refer his conduct to the Ombudsman for deeper digging.

Office of the Ombudsman:

- Investigate Pronto: Probe for RA 6713 and 3019 violations—conflict and bad faith need answers. Suspension pending inquiry keeps COA’s image intact.

- Audit COA: Check if Mallillin’s a lone wolf or part of a pattern. Commissioners don’t go rogue without some nudge.

Integrated Bar of the Philippines:

- Disbarment Probe: If Mallillin’s a lawyer, start proceedings under Rule 138. Gross misconduct’s a slam dunk—don’t let it slide.

- Ethics Seminar: Mandatory for public officer-lawyers. Prevention beats reaction.

Legislative Reforms:

- Amend COA Law: Explicitly ban commissioners from court appearances tied to auditees—plug the loophole Mallillin exploited.

- Vetting Overhaul: Require Senate confirmation before ad interim appointees act. Mallillin’s 15-day rampage shows why.

- Whistleblower Shield: Protect COA staff who flag internal breaches. Independence isn’t just top-down.

The Verdict: A Catalyst for Change or More of the Same?

Mallillin’s Supreme Court stunt isn’t just a personal blunder—it’s a stress test for Philippine constitutional law. He’s violated Article IX-A, RA 6713, and COA’s core ethos, risking suspension, jail, or a revoked law license. The Court’s precedents demand accountability, and the public deserves no less. This isn’t about one man; it’s about a system teetering on trust. Act fast—because if COA falls, the dominoes won’t stop. Time to lawyer up, Philippines, but this time, for the right side.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

- “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

- “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

- “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

- “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

- “No Special Jail for Crooks!” Boying Remulla Slams VIP Perks for Flood Scammers

- “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

- “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

- “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

- “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

- “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

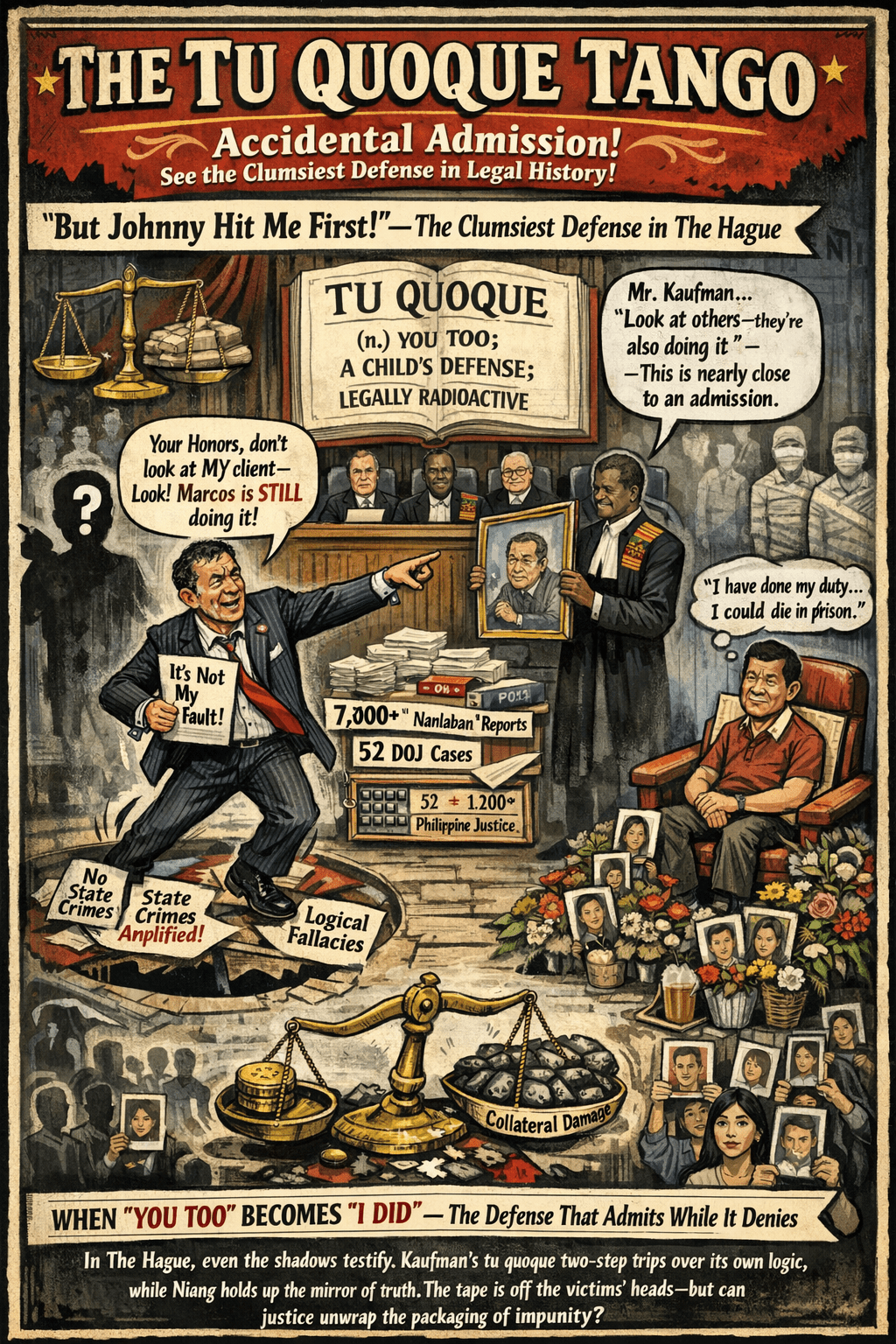

- $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

Leave a comment