By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — July 8, 2025

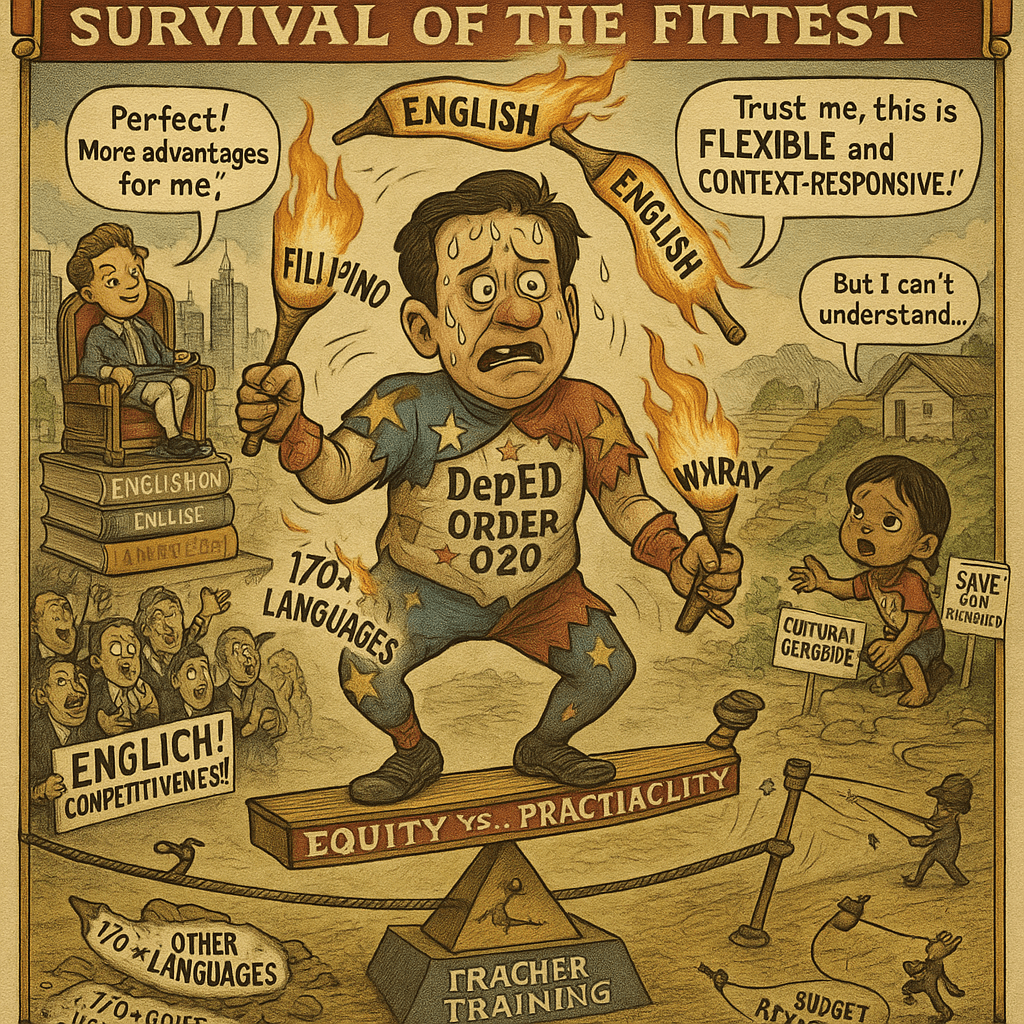

IN A nation woven from over 170 languages, the Philippines faces a defining moment in its education system. The Department of Education’s (DepEd) new policy, DepEd Order No. 020, s. 2025(PDF), dismantles the mandatory use of Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE) for Kindergarten to Grade 3, crowning Filipino and English as the primary media of instruction (MOI) starting School Year 2025–2026, with regional and Indigenous languages demoted to supporting roles [Manila Bulletin, 2025].

Enacting Republic Act No. 12027, the policy aims to untangle the knots of multilingual classrooms—scarce resources, undertrained teachers, and inconsistent execution [Manila Bulletin, 2025]. But is this a visionary leap toward educational equity, or a reckless retreat that sacrifices cultural identity and leaves marginalized children stranded?

The 2009 MTB-MLE policy, codified in the Enhanced Basic Education Act of 2013 (RA 10533), drew on UNESCO’s evidence that early instruction in a child’s first language boosts literacy and self-esteem, particularly for rural and Indigenous learners [Manila Bulletin, 2025]. Yet DepEd now cites logistical failures, spotlighted by the 2024 EDCOM 2 study, which revealed chaos in diverse classrooms where teachers juggled multiple dialects without adequate support [Manila Bulletin, 2025]. The solution? A “flexible, context-responsive” framework prioritizing Filipino and English, with translanguaging to bridge gaps [Manila Bulletin, 2025]. But whose flexibility does this serve, and who pays the price?

A Lifeline or a Shortcut? The Case for Change

DepEd’s pivot has its defenders. The Philippines’ dismal 2022 PISA rankings—second to last globally—signal a literacy crisis demanding urgent action [Manila Bulletin, 2025]. Emphasizing Filipino and English, the languages of higher education and global markets, could equip students for competitive exams and careers.

The policy’s four scenarios—from Filipino/English in multilingual settings (Scenario A) to Indigenous languages in specific IP programs (Scenario D)—offer tailored approaches [Manila Bulletin, 2025]. By leaning on existing materials in national languages, DepEd sidesteps the chronic shortage of mother tongue resources, a barrier flagged by the 2024 EDCOM 2 report [Manila Bulletin, 2025].

But this pragmatism smells of defeat. The Philippines allocates just 3.2% of GDP to education, far below the 4–6% benchmark for developing nations [Manila Bulletin, 2025]. A P12 billion cut to DepEd’s 2025 budget tightens the screws further [Manila Bulletin, 2025]. Instead of investing in teacher training or localized materials to salvage MTB-MLE, the government has opted for the path of least resistance. Is this a strategic recalibration, or a white flag waved at systemic underfunding?

Equity and Identity on the Chopping Block

The policy’s critics warn of dire consequences for the marginalized—poor, rural, and Indigenous children who rely on their mother tongue to access education. UNESCO’s research shows that early mother tongue instruction enhances literacy and confidence, especially for disadvantaged groups [Manila Bulletin, 2025]. A 2022 PBEd statement argued that sidelining mother tongues risks cultural erosion and wider learning gaps [Manila Bulletin, 2025].

In rural areas, where Filipino and English are often foreign, children may face a curriculum as decipherable as ancient script. Scenario C, allowing mother tongue use in monolingual classes, is a hollow gesture, limited by strict criteria like official orthography and trained teachers—rarities in underserved regions [Manila Bulletin, 2025].

Worse, the policy threatens cultural annihilation. With 245 languages in the Philippines, only 19 were supported under MTB-MLE [Manila Bulletin, 2025]. Reducing regional and Indigenous languages to “auxiliary” status could hasten linguistic extinction, especially for smaller ethnolinguistic groups. A 2012 Cultural Survival article emphasized mother tongue instruction as a bulwark for Indigenous heritage [Manila Bulletin, 2025]. Scenario D preserves Indigenous languages for IP education, but its limited scope leaves many Ifugao, Waray, or Tausug children navigating a system that devalues their native voice [Manila Bulletin, 2025].

Faces of the Fallout: The Human Cost

Picture Maria, a Tagalog-speaking teacher in a Mindanao public school. Her classroom is a linguistic kaleidoscope—students speak Cebuano, Tausug, and Maguindanao. Now mandated to teach in Filipino, a language many students barely grasp, she struggles with translanguaging, a technique she’s untrained for. With only 45% of schools having principals, she lacks guidance [Manila Bulletin, 2025]. “I’m trying to reach them,” Maria sighs, “but I’m juggling languages I don’t know.” Her lesson time shrinks as she translates, her exhaustion palpable.

Then there’s Lito, an Ifugao first-grader in a remote Cordillera village. His school qualifies for Scenario D, using Ifugao as the MOI, but it depends on one teacher fluent in the language—a unicorn in a system where 62% of teachers work outside their specialization [Manila Bulletin, 2025]. Without consistent IPEd support, Lito’s lessons may default to Filipino, a language his family rarely speaks. His mother, a farmer, frets: “If he can’t learn in Ifugao, will he give up on school?” For Lito, the policy’s promise of flexibility is a faint whisper against the din of resource scarcity.

Contrast this with Anna, a Kindergartener in an elite Manila private school. Her English-centric education, bolstered by private tutors, aligns perfectly with the new policy. While Lito stumbles, Anna thrives, her English fluency widening the urban-rural divide. Private schools, long exempt from MTB-MLE’s constraints, are poised to outpace underfunded public ones, deepening inequities [Manila Bulletin, 2025].

A House of Cards: Systemic Barriers

The policy’s fate rests on execution, but the deck is stacked against it. Only 45% of public schools have principals to steer implementation, and 62% of teachers lack specialization in their subjects, let alone multilingual skills [Manila Bulletin, 2025]. Translanguaging requires robust training, but a P12 billion budget cut in 2025 undermines such investments [Manila Bulletin, 2025].

The Comprehensive Rapid Literacy Assessment (CRLA) and Basic Education Monitoring and Evaluation Framework (BEMEF) promise oversight, but without transparent, disaggregated data, how will we track the policy’s impact on rural or Indigenous learners [Manila Bulletin, 2025]? Language mapping, slated for October 2025, aims to tailor solutions, but relies on surveys that overstretched schools may struggle to conduct [Manila Bulletin, 2025].

The inclusion of Filipino Sign Language for deaf learners, per RA 11106, is a rare win [Manila Bulletin, 2025]. Yet chronic underfunding—exacerbated by budget accounting that pads education figures with non-core items like military academies—sets this reform on a fragile foundation [Manila Bulletin, 2025].

Charting a Bolder Course: Solutions for Equity

This policy doesn’t have to spell doom for linguistic diversity or equitable education, but it demands audacious action. DepEd must launch Conditional Cash Transfers for Language Support, subsidizing local-language tutoring for poor and rural students to bridge the gap to Filipino and English. Linguistic Equity Audits, mandated annually, should use disaggregated BEMEF data to monitor impacts on Indigenous, rural, and low-income learners [Manila Bulletin, 2025].

Teacher training must prioritize translanguaging and multilingual pedagogy, targeting the 62% of educators teaching outside their expertise [Manila Bulletin, 2025]. Above all, the government must reverse DepEd’s budget cuts and meet the 4–6% GDP benchmark for education spending [Manila Bulletin, 2025]. Without this, the policy risks becoming another reform undone by neglect.

As Maria, Lito, and millions like them navigate this linguistic shift, the Philippines faces a choice: invest in a system that uplifts every child, or settle for one that leaves the most vulnerable deciphering their future alone?

Key Citations

- DepEd Order No. 020, s. 2025 (PDF) – Details the new MOI policy for Kindergarten to Grade 3.

- Republic Act No. 12027 – Legislative basis for discontinuing mandatory MTB-MLE.

- Enhanced Basic Education Act of 2013 (RA 10533) – Institutionalized MTB-MLE.

- UNESCO: Mother Tongue Instruction – Evidence on benefits of mother tongue education.

- 2024 EDCOM 2 Report – Highlights challenges in MTB-MLE implementation.

- P12 Billion DepEd Budget Cut 2025 – Reports on DepEd’s 2025 budget reduction.

- 2022 PBEd Statement on MTB-MLE – Advocates for maintaining MTB-MLE.

- 2012 Cultural Survival: MTB-MLE in the Philippines – Discusses cultural preservation through mother tongue instruction.

- RA 11106: Filipino Sign Language – Mandates FSL for deaf learners.

- Manila Bulletin: Mother Tongue No Longer Required – News report on DepEd’s policy shift.

Leave a comment