By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — July 31, 2025

The Gist: Supreme Court’s Constitutional Con Job in a Nutshell

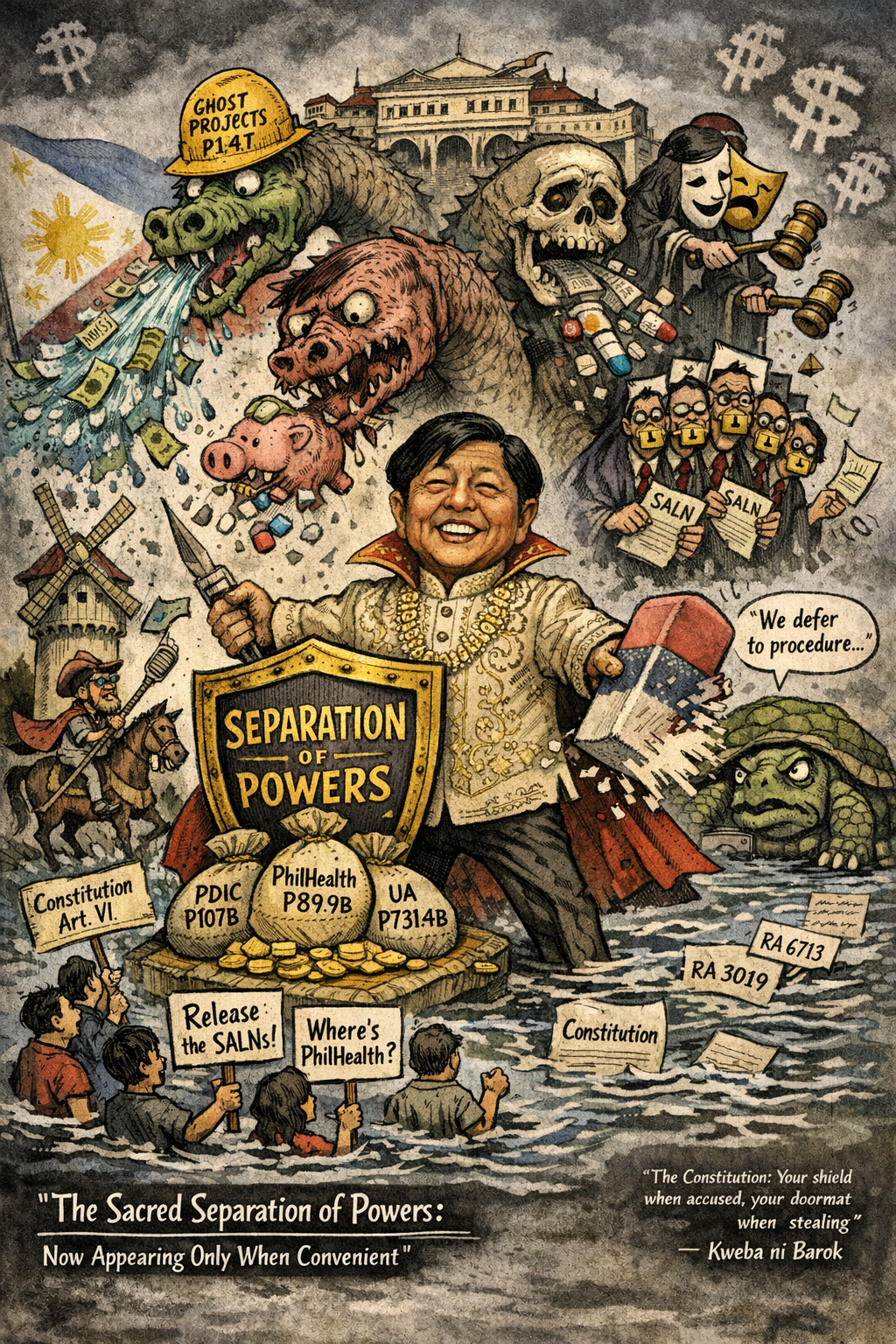

The Philippine Supreme Court’s July 25, 2025, ruling on Vice President Sara Duterte’s impeachment complaint is a judicial travesty dressed up as constitutional fidelity. By redefining “initiate” and imposing a gauntlet of procedural hurdles, the Court has gutted Congress’s exclusive impeachment powers, shielded a political heavyweight, and betrayed the Filipino people’s demand for accountability. Justice Adolfo Azcuna, one of the Philippines’ legal luminaries and a 1986 Constitutional Commission framer, joins other prominent voices in condemning the Supreme Court’s ruling, exposing it for what it is: a shameless judicial power grab that protects elites and erodes democracy. This analysis dissects the Court’s reasoning, exposes its conflicts of interest, and charts the catastrophic fallout for the rule of law. Congress must fight back, the public must mobilize, and the Court must be reminded: it’s not above the Constitution.

1. Opening Salvo: The Supreme Court’s Constitutional Heist

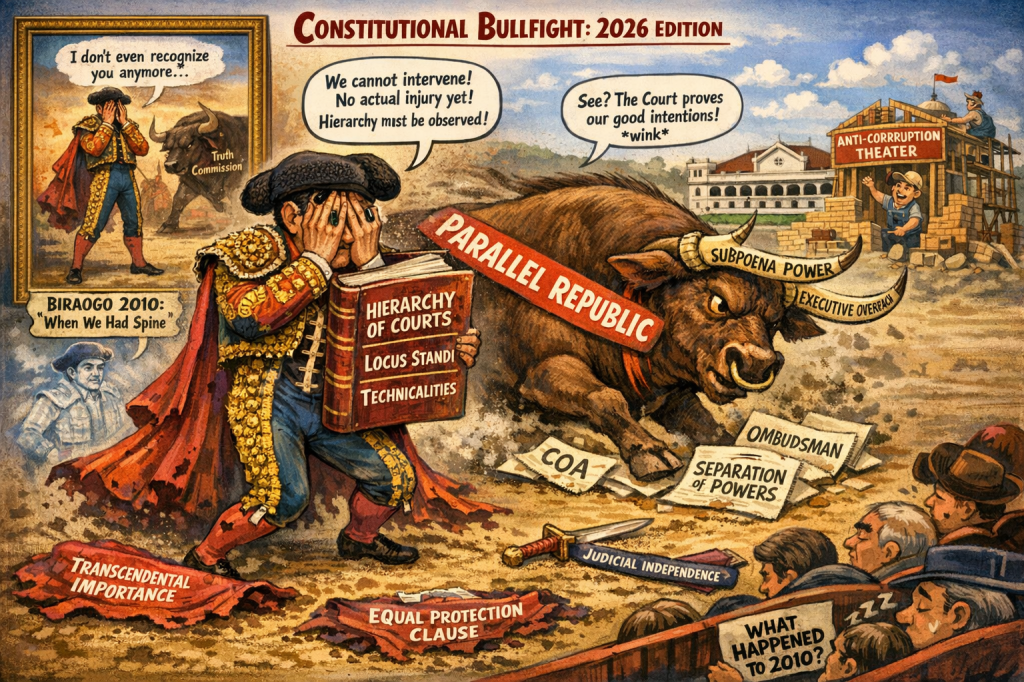

Oh, how precious that the Supreme Court thinks it can rewrite the Constitution under the guise of “interpretation.” On July 25, 2025, the Court, in a unanimous 97-page ruling penned by Senior Associate Justice Marvic Leonen, declared the impeachment complaint against Vice President Sara Duterte unconstitutional, citing the one-year bar rule under Article XI, Section 3(5). But the real crime isn’t the technicality—it’s the Court’s audacious redefinition of “initiate” and its imposition of quasi-judicial shackles on the House of Representatives’ exclusive power to start impeachment proceedings. This isn’t justice; it’s a judicial mugging of Congress’s constitutional prerogative.

Enter Justice Adolfo Azcuna, a framer of the 1987 Constitution and former Supreme Court justice, whose July 30, 2025, Social media post is a constitutional Molotov cocktail. Azcuna doesn’t just critique; he eviscerates the Court’s ruling as a betrayal of accountability, a violation of separation of powers, and a self-serving act by justices who are themselves impeachable. While the Court plays gatekeeper to protect its own, Azcuna stands as the constitutional prophet, reminding us that public office is a trust, not a fortress. This ruling isn’t about due process—it’s about ensuring the powerful stay untouchable.

2. Constitutional Beatdown: Shredding the Court’s Reasoning

Let’s dismantle this judicial travesty with the precision of a legal scalpel. The Supreme Court’s ruling hinges on a tortured redefinition of “initiate” under Article XI, Section 3(1), which grants the House the exclusive power to start impeachment cases. The Court now demands prior notice, hearings, evidence attachment, and proof that representatives read and understood the charges. Azcuna calls this what it is: a judicial amendment to the Constitution, which even the Court lacks the power to enact. Let’s break it down.

A. Violation of Congressional Exclusivity

The 1987 Constitution is crystal clear: “The House of Representatives shall have the exclusive power to initiate all cases of impeachment” (Art. XI, Sec. 3(1)). Exclusive means exclusive—no judicial babysitting required. Yet, the Court’s new rules turn the House’s prerogative into a bureaucratic maze. In Francisco v. House of Representatives (2003), the Court defined “initiate” as the filing of the complaint and its referral to the House Committee on Justice. Simple. Effective. Constitutional. Now, the Court’s 2025 ruling adds layers of red tape, requiring evidence and comprehension tests for lawmakers. This isn’t interpretation; it’s legislation from the bench, usurping Congress’s rule-making authority under Art. XI, Sec. 3(8), which mandates that Congress’s rules “effectively carry out the purpose” of impeachment—accountability, not obstruction.

B. Due Process Distortion

The Court cloaks its overreach in the sanctimonious garb of “due process.” Azcuna demolishes this pretense: impeachment is a sui generis political process, not a criminal trial. Article III, Section 1 guarantees due process for deprivations of life, liberty, or property—none of which are at stake in impeachment. Public office is a trust, not a property right (Corona v. Senate, 2012). In Gutierrez v. House of Representatives (2011), the Court itself held that due process in legislative proceedings is flexible, prioritizing function over form. So why is the Court now demanding judicial-style hearings at the initiation stage? It’s a deliberate roadblock, designed to make impeachment as likely as a Manila traffic jam clearing by noon.

C. Separation of Powers Annihilation

The Constitution’s impeachment framework is a constituent power—a sovereign act delegated exclusively to Congress. Art. XI, Sec. 3(8) empowers Congress, not the Court, to craft rules to “effectively carry out” impeachment’s purpose. By imposing its own procedural wishlist, the Court violates the separation of powers doctrine, which demands that “where the Constitution puts it, there it should lie” (Azcuna, 2025). The Court’s role under Art. VIII, Sec. 1 is to check grave abuse of discretion, not to rewrite the playbook for a co-equal branch. This isn’t judicial review; it’s judicial supremacy, a dangerous precedent that could let the Court meddle in other constituent powers, like treaty ratification or constitutional amendments.

D. Retroactive Rule-Making Shenanigans

Azcuna rightly calls out the Court’s retroactive application of its new “initiate” definition as unfair. In Francisco (2003), the Court set a clear standard for initiation. Changing the rules mid-game to block Duterte’s impeachment violates legal certainty and fairness. The 1986 Constitutional Commission, where Azcuna served, deliberately lowered vote thresholds from the 1935 Constitution (2/3 House, 3/4 Senate) to 1/3 House and 2/3 Senate to make accountability easier (Bernas, The 1987 Constitution: A Commentary, 2009). The Court’s new hurdles reverse this intent, effectively amending the Constitution without a plebiscite. Cute, but unconstitutional.

3. Political Reality Check: Elites Protecting Elites

Who benefits from this ruling? Spoiler: not the Filipino people. The Supreme Court’s decision conveniently shields Vice President Sara Duterte, daughter of former President Rodrigo Duterte, whose appointees dominate the bench (12 of 15 justices, per TIME, July 2025). This isn’t a coincidence; it’s a pattern. The ruling ensures that impeachable officials—presidents, vice presidents, justices—can hide behind procedural technicalities, turning impeachment into a pipe dream. The one-year bar rule (Art. XI, Sec. 3(5)), meant to prevent harassment, becomes a get-out-of-jail-free card when paired with the Court’s new requirements.

This decision fits a broader trend of judicial protectionism. From the Sereno impeachment (2018), where the Court controversially allowed a quo warranto petition to oust a chief justice, to the Corona impeachment (2012), where due process was respected without judicial meddling, the judiciary has a history of bending over backwards for the powerful. The Duterte-Marcos feud, a political soap opera, now gets a judicial script rewrite, delaying accountability until February 2026 (Rappler, July 2025). Meanwhile, Filipinos are left with a system where the elite protect their own, and the Constitution’s promise of accountability is reduced to a campaign slogan.

4. Precedential Carnage: The Court’s Legal Hypocrisy

The Supreme Court’s ruling doesn’t just contradict Azcuna—it spits in the face of its own precedents. Let’s tally the damage:

- Francisco v. House of Representatives (2003): The Court defined “initiate” as filing and referral, no bells or whistles required. The 2025 ruling’s new requirements—notice, hearings, evidence—overturn this without justification, violating stare decisis.

- Gutierrez v. House of Representatives (2011): The Court upheld flexible due process in impeachment, rejecting rigid judicial standards. Now, it demands quasi-judicial procedures, contradicting its own logic.

- Corona v. Senate (2012): The impeachment of Chief Justice Renato Corona showed how the process should work—Congress handled initiation and trial without judicial micromanagement. The Court’s current meddling makes Corona’s case look like a fairy tale.

- Sereno v. Republic (2018): The Court’s willingness to bypass impeachment via quo warranto already raised red flags about judicial overreach. This ruling doubles down, confirming the Court’s addiction to power.

The Court’s selective application of principles is glaring. It invokes due process when it suits the powerful but ignores it when ousting a chief justice via a non-impeachment route. This isn’t law; it’s legal cherry-picking.

5. Institutional Conflict: Judges Judging Themselves

Azcuna’s most damning point is the Court’s conflict of interest. The principle of nemo judex in causa sua—no one should judge their own case—is a cornerstone of fairness. Yet, the Supreme Court, whose justices are impeachable under Art. XI, Sec. 2, dares to craft rules governing their own potential removal. This isn’t just a conflict; it’s a constitutional scandal. With 12 of 15 justices appointed by Rodrigo Duterte, the optics are catastrophic. As political analyst Richard Heydarian notes, the ruling “resurrects suspicions of bias” among Duterte appointees (TIME, July 2025). The Court’s claim to impartiality is as convincing as a fox guarding the henhouse.

This conflict undermines judicial independence, a principle the Court loves to preach but fails to practice. Canon 2 of the Code of Judicial Conduct demands judges avoid even the appearance of impropriety. Ruling on impeachment rules while being subject to them? That’s not just impropriety—it’s a neon sign flashing “bias.” The Court’s self-interest taints its legitimacy, eroding public trust in a judiciary already battered by perceptions of political capture.

6. Impact Assessment: Democracy Takes a Hit

The fallout from this ruling is a slow-motion disaster for Philippine democracy. Let’s break it down:

A. Immediate Impact

- Sara Duterte’s Protection: The ruling delays her impeachment until February 2026, letting her skate despite multiple complaints tied to her tenure (Rappler, July 2025). This fuels the Duterte-Marcos feud, with Speaker Martin Romualdez and Senator Chiz Escudero caught in the crossfire as they navigate the 20th Congress (Rappler, July 2025).

- Political Chilling Effect: House members, already wary of political blowback, now face a judicial gauntlet to initiate impeachment. Expect fewer complaints, even against blatantly corrupt officials.

B. Systemic Erosion

- Accountability in Tatters: Impeachment, the Constitution’s primary tool for holding high officials accountable, is now a procedural quagmire. As Azcuna warns, this “derails” the Constitution’s intent to make accountability easier (Viber post, July 2025).

- Rule of Law Hypocrisy: The Court’s claim to uphold “just law” (AP News, July 2025) rings hollow when it prioritizes form over substance. UP Law professor Paolo Tamase calls it “judicial overreach” (Rappler, July 2025), and he’s not wrong.

C. Democratic Fallout

- Public Trust Crisis: Filipinos already distrust institutions—only 33% trust the judiciary, per a 2024 SWS survey. This ruling, seen as shielding Duterte, could push that number lower. Jean Encinas-Franco notes that many Filipinos may wrongly believe Duterte was “acquitted” (TIME, July 2025), deepening cynicism.

- Polarization Amplified: The ruling fans the flames of political division, with Duterte supporters hailing it as a win and critics like Rep. Leila de Lima decrying its lack of transparency (TIME, July 2025). The 2025 midterms will be a circus, with impeachment as the main act.

7. Recommendations with Bite: Fighting Back Against Judicial Overreach

This ruling is a constitutional gut punch, but it’s not game over. Here’s how to fight back:

A. Congressional Pushback

- File a Motion for Reconsideration: The House, led by Speaker Romualdez, must challenge the ruling, citing Francisco and Gutierrez to demand restoration of its exclusive power (Rappler, July 2025).

- Amend House Rules: Under Art. XI, Sec. 3(8), Congress can revise its impeachment rules to clarify “initiate” as filing and referral, nullifying the Court’s overreach. Make it bulletproof against judicial review.

- Impeach Justices (Yes, Really): If the Court persists, the House could, in theory, initiate impeachment against justices for grave abuse of discretion. It’s a nuclear option, but it’s on the table.

B. Constitutional Remedies

- Push for Amendment: A constitutional convention or people’s initiative could codify Azcuna’s view, explicitly barring judicial meddling in impeachment rules. This is a long shot but worth exploring.

- Legislative Clarification: Congress could pass a law defining impeachment procedures, reinforcing its exclusive authority while addressing due process concerns to avoid judicial scrutiny.

C. Public Pressure

- Mobilize Civil Society: Groups like the Integrated Bar of the Philippines and citizen watchdogs must amplify Azcuna’s critique, organizing protests and forums to demand accountability.

- Weaponize Social Media: Filipinos are X powerhouses—use hashtags like #NoToJudicialOverreach to make this a national conversation. Public outrage can force the Court to reconsider.

- Demand Transparency: Call for public disclosure of justices’ voting rationales and recusals, especially given the Duterte appointee issue. Sunlight is the best disinfectant.

Bottom Line: A Democracy in Peril

The Supreme Court’s impeachment ruling is a betrayal of the Filipino people, dressed up as constitutional piety. By redefining “initiate” and imposing impossible procedural hurdles, the Court has neutered Congress’s exclusive power, protected political elites like Sara Duterte, and undermined the Constitution’s promise of accountability. Justice Azcuna, with his unimpeachable credentials as a 1986 framer, exposes this for what it is: a judicial coup against democracy. The ruling’s immediate impact—shielding Duterte until 2026—pales in comparison to its systemic damage: eroded accountability, weakened rule of law, and shattered public trust. Congress must fight back, the public must rise, and the Court must be reminded that it serves the Constitution, not the other way around. If this ruling stands, impeachment becomes a relic, and the powerful become untouchable. The Filipino people deserve better.

Key Citations

Constitutional Provisions

- 1987 Constitution of the Philippines, Art. XI, Sec. 3(1), (5), (8)

- 1987 Constitution of the Philippines, Art. III, Sec. 1

- 1987 Constitution of the Philippines, Art. VIII, Sec. 1

Supreme Court Cases

- Francisco v. House of Representatives, G.R. No. 160261 (2003)

- Gutierrez v. House of Representatives, G.R. No. 193459 (2011)

- Republic v. Sereno, G.R. No. 237428 (2018)

Media and Expert Sources

- Rappler, “Supreme Court decision blocks Sara Duterte impeachment trial,” July 2025

- Rappler, “Sara Duterte impeachment: Implications of Supreme Court decision,” July 2025

- Rappler, “Best: The shocking Supreme Court decision on Sara Duterte impeachment trial,” July 2025

- TIME, “Philippines: Why the Supreme Court Blocked Sara Duterte’s Impeachment,” July 2025

- AP News, “Philippines’ Supreme Court halts impeachment trial of Vice President Sara Duterte,” July 2025

Other Sources

- Azcuna, A. S., Social Media Post, July 30, 2025

- Bernas, J., The 1987 Constitution: A Commentary (2009)

- Code of Judicial Conduct, Canon 2

- SWS Survey, “Trust in Institutions,” 2024

Disclaimer: This is legal jazz, not gospel. It’s all about interpretation, not absolutes. So, listen closely, but don’t take it as the final word.

- “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — June 20, 2025 A CONSTITUTIONAL TRAINWRECK IN SLOW MOTION The Philippine Senate had one job: try Sara Duterte. Instead, on June 10, 2025, 18 senator-jurors staged a constitutional coup by remanding the impeachment articles back to the House—a move so legally dubious, it reeks of political arson[1]. The Constitution’s… Read more: “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him)

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — June 20, 2025 A CONSTITUTIONAL TRAINWRECK IN SLOW MOTION The Philippine Senate had one job: try Sara Duterte. Instead, on June 10, 2025, 18 senator-jurors staged a constitutional coup by remanding the impeachment articles back to the House—a move so legally dubious, it reeks of political arson[1]. The Constitution’s… Read more: “Forthwith” to Farce: How the Senate is Killing Impeachment—And Why Enrile’s Right (Even If You Can’t Trust Him) - “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

The Executive Secretary Screams from the Grave of His Own Political Funeral By Louis “Barok” C. Biraogo — November 22, 2025 1. The Resignation That Wasn’t: A Love Story in Two Contrasting Scripts Malacañang: “He stepped down out of delicadeza. So noble. So graceful. So very voluntary.”Lucas Bersamin, live on national television: “Hindi ako nag-resign.”… Read more: “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!”

The Executive Secretary Screams from the Grave of His Own Political Funeral By Louis “Barok” C. Biraogo — November 22, 2025 1. The Resignation That Wasn’t: A Love Story in Two Contrasting Scripts Malacañang: “He stepped down out of delicadeza. So noble. So graceful. So very voluntary.”Lucas Bersamin, live on national television: “Hindi ako nag-resign.”… Read more: “HINDI AKO NAG-RESIGN!” - “I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM. Send load!”

A Cat-astrophic Error: Globe Telecom’s SIM Registration Tailspin

A Cat-astrophic Error: Globe Telecom’s SIM Registration Tailspin - “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — August 2, 2025 Executive Summary: Can Marcos Break the Cycle of Corruption? President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s fiery 2025 SONA pledge to expose and prosecute corruption in failed flood control projects taps into public fury over persistent flooding and squandered funds. His call to shame negligent officials and publish project… Read more: “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — August 2, 2025 Executive Summary: Can Marcos Break the Cycle of Corruption? President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s fiery 2025 SONA pledge to expose and prosecute corruption in failed flood control projects taps into public fury over persistent flooding and squandered funds. His call to shame negligent officials and publish project… Read more: “Mahiya Naman Kayo!” Marcos’ Anti-Corruption Vow Faces a Flood of Doubt - “Meow, I’m calling you from my new Globe SIM!”

A Cat-astrophic Error: Globe Telecom’s SIM Registration Tailspin

A Cat-astrophic Error: Globe Telecom’s SIM Registration Tailspin - “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

Why Ombudsman Remulla’s “No-Plunder” Gambit Is the Smartest Anti-Corruption Move Since the Wheel By Louis “Barok” C. Biraogo — November 4, 2025 THE MOB’S HOLY WAR: “PLUNDER!” SCREAMED LOUDER THAN LOGIC The mob is drunk on drama. PLUNDER! PLUNDER! PLUNDER! — chanted like a war cry at a frat hazing. Meanwhile, Ombudsman Jesus Crispin “Boying”… Read more: “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT

Why Ombudsman Remulla’s “No-Plunder” Gambit Is the Smartest Anti-Corruption Move Since the Wheel By Louis “Barok” C. Biraogo — November 4, 2025 THE MOB’S HOLY WAR: “PLUNDER!” SCREAMED LOUDER THAN LOGIC The mob is drunk on drama. PLUNDER! PLUNDER! PLUNDER! — chanted like a war cry at a frat hazing. Meanwhile, Ombudsman Jesus Crispin “Boying”… Read more: “PLUNDER IS OVERRATED”? TRY AGAIN — IT’S A CALCULATED KILL SHOT - “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

Fajardo’s Final Lesson: You Can’t Fix a System That Rewards the People Breaking It By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — January 31, 2026 IN A country where the poor wade through floodwaters that rise faster than our leaders’ excuses, Rossana Fajardo’s resignation from the Independent Commission for Infrastructure (ICI)—coupled with her bleak prophecy that rooting… Read more: “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus”

Fajardo’s Final Lesson: You Can’t Fix a System That Rewards the People Breaking It By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — January 31, 2026 IN A country where the poor wade through floodwaters that rise faster than our leaders’ excuses, Rossana Fajardo’s resignation from the Independent Commission for Infrastructure (ICI)—coupled with her bleak prophecy that rooting… Read more: “Several Lifetimes,” Said Fajardo — Translation: “I’m Not Spending Even One More Day on This Circus” - “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

HAVE you heard of “Shimenet”? No, it’s not a secret government program, a new flavor of ice cream, or a hidden island paradise. It’s the latest meme sensation sweeping the Philippines, thanks to an unexpected gaffe by Vice President Sara Duterte during a budget hearing. Turns out, even the hallowed halls of Congress can’t escape… Read more: “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget

HAVE you heard of “Shimenet”? No, it’s not a secret government program, a new flavor of ice cream, or a hidden island paradise. It’s the latest meme sensation sweeping the Philippines, thanks to an unexpected gaffe by Vice President Sara Duterte during a budget hearing. Turns out, even the hallowed halls of Congress can’t escape… Read more: “Shimenet”: The Term That Broke the Internet and the Budget - “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — June 28, 2025 A Fisherman’s Dreams Dashed on the Waves Tolomeo Forones, a 70-year-old fisherman from Masinloc, Philippines, once sailed to Scarborough Shoal with hope in his heart and nets full of promise. His hands, etched with the labor of decades, hauled in catches worth $705 every three months—enough… Read more: “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — June 28, 2025 A Fisherman’s Dreams Dashed on the Waves Tolomeo Forones, a 70-year-old fisherman from Masinloc, Philippines, once sailed to Scarborough Shoal with hope in his heart and nets full of promise. His hands, etched with the labor of decades, hauled in catches worth $705 every three months—enough… Read more: “We Did Not Yield”: Marcos’s Stand and the Soul of Filipino Sovereignty - “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C Biraogo — April 29, 2025 THE measure of a life is not in years alone, but in the luminous traces it leaves behind—echoes of integrity, acts of courage, and the quiet, steadfast labor of love for one’s community. In the passing of Edgardo Bautista Espiritu, the Upsilon Sigma Phi fraternity, the… Read more: “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C Biraogo — April 29, 2025 THE measure of a life is not in years alone, but in the luminous traces it leaves behind—echoes of integrity, acts of courage, and the quiet, steadfast labor of love for one’s community. In the passing of Edgardo Bautista Espiritu, the Upsilon Sigma Phi fraternity, the… Read more: “We Gather Light to Scatter”: A Tribute to Edgardo Bautista Espiritu - $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — July 10, 2025 LET’S not pretend the International Criminal Court’s case against Rodrigo Duterte is a grand geopolitical chess game. It’s simpler, uglier: a reckoning for a man who turned the Philippines into a slaughterhouse, leaving 6,000 to 30,000 dead in his “war on drugs.” Yet, here we are,… Read more: $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — July 10, 2025 LET’S not pretend the International Criminal Court’s case against Rodrigo Duterte is a grand geopolitical chess game. It’s simpler, uglier: a reckoning for a man who turned the Philippines into a slaughterhouse, leaving 6,000 to 30,000 dead in his “war on drugs.” Yet, here we are,… Read more: $150M for Kaufman to Spin a Sinking Narrative - $2 Trillion by 2050? Manila’s Economic Fantasy Flimsier Than a Taho Cup

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — July 18, 2025 STEP right up to the greatest economic spectacle in Southeast Asia! The Philippines’ Department of Economy, Planning and Development (DEPDev) is hawking a $2 trillion economy by 2050, a vision so dazzling it could outshine a Quiapo firecracker stall. Secretary Arsenio Balisacan, with the bravado of… Read more: $2 Trillion by 2050? Manila’s Economic Fantasy Flimsier Than a Taho Cup

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — July 18, 2025 STEP right up to the greatest economic spectacle in Southeast Asia! The Philippines’ Department of Economy, Planning and Development (DEPDev) is hawking a $2 trillion economy by 2050, a vision so dazzling it could outshine a Quiapo firecracker stall. Secretary Arsenio Balisacan, with the bravado of… Read more: $2 Trillion by 2050? Manila’s Economic Fantasy Flimsier Than a Taho Cup

Leave a reply to From Guardians to Gravediggers: IBP and SC’s Betrayal in Duterte v. House – KWEBA ni BAROK Cancel reply