Why Hinging The Hague’s Case on a Shady Snitch Could Backfire

By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — September 10, 2025

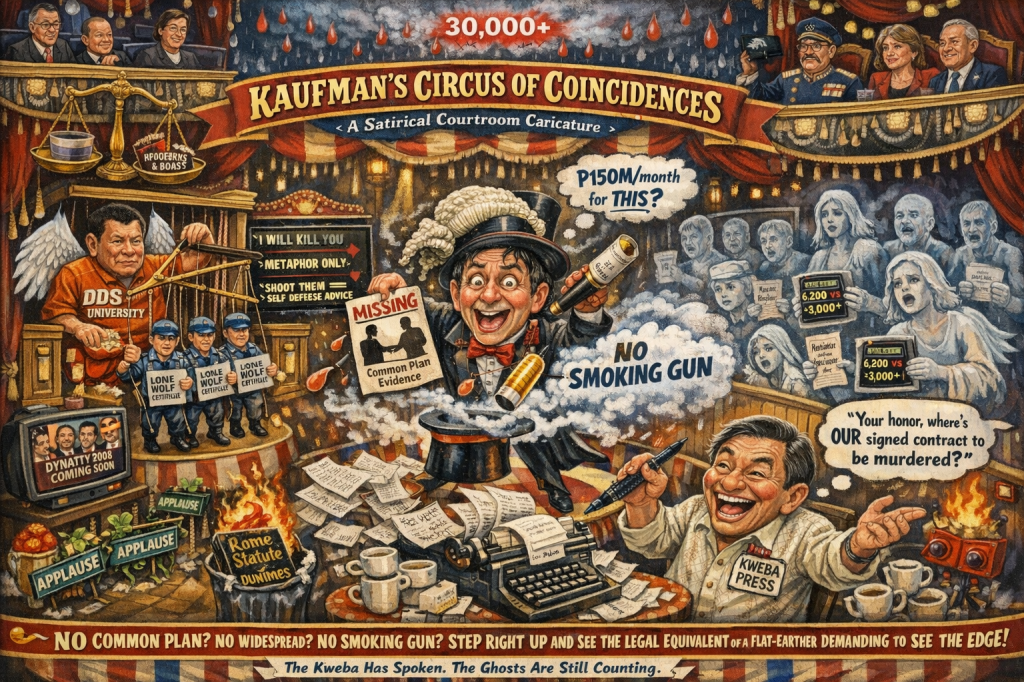

MY, what a splendid halo-halo of backstabbing and bureaucratic wizardry! Royina Garma, the disgraced former Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office (PCSO) general manager and retired police colonel, has decided to play turncoat, snitching on former President Rodrigo Duterte to the International Criminal Court (ICC). Her testimony, dripping with the stench of self-preservation, is the latest act in a legal circus that’s equal parts tragedy and farce. Department of Justice (DOJ) Secretary Jesus Crispin Remulla, meanwhile, dances through this minefield like a legal Houdini, while the ICC fumbles its high-stakes case like a drunk juggler. Buckle up for a scalding takedown of Garma’s credibility, a cynical salute to Remulla’s maneuvering, and a warning about the clown show threatening Philippine sovereignty and Duterte’s legacy.

I. Garma’s Great Con: A Witness as Trustworthy as a Three-Peso Bill

Royina Garma, the ICC’s newfound darling, is less a whistleblower than a snake oil peddler peddling tales of Duterte’s “Davao model” to save her own skin. Deported from the United States after a failed asylum bid, she barely grazed Manila’s tarmac before jetting to Malaysia to cozy up with ICC prosecutors. Her story? A reward-based killing system allegedly ordered by Duterte himself. But let’s not anoint her as a martyr just yet—her credibility is shakier than a Quiapo knockoff Rolex.

Under Philippine law, Garma’s testimony is a legal dumpster fire. Rule 132, Section 11 of the Rules of Court allows impeachment of a witness’s credibility through evidence of bias, interest, or—here’s the kicker—pending criminal charges. Garma’s got a rap sheet featuring murder and frustrated murder for her alleged role in the 2020 assassination of PCSO board secretary Wesley Barayuga, charges that scream moral turpitude louder than a Divisoria hawker. The Supreme Court’s ruling in People of the Philippines v. Sergio Bato and Abraham Bato (G.R. No. 113804, January 16, 1998) is clear: witnesses with their own axes to grind, especially those angling for leniency, are as reliable as a jeepney’s brakes in a monsoon. Garma’s sudden “truth-teller” act reeks of a plea deal to dodge Revised Penal Code (RPC) Article 248 penalties, which carry reclusion perpetua for murder.

The ICC’s own rules bury her deeper. Article 69(7) of the Rome Statute demands that evidence be weighed for probative value, and Garma’s baggage—murder charges, a rejected asylum bid, and a history as Duterte’s loyal foot soldier—makes her testimony about as convincing as a teleserye plot twist. Her “Davao model” claims need corroboration, or they’re just spicy chismis. Garma’s not a hero; she’s a cornered rat squealing for immunity, and the ICC’s betting on her is like trusting a fox to guard the henhouse.

II. Remulla’s Legal Sorcery: A Three-Card Monte That Would Make Machiavelli Blush

DOJ Secretary Jesus Crispin Remulla deserves a standing ovation for pulling off a legal high-wire act that leaves everyone else in the dust. Caught between Philippine sovereignty, witness protection duties, and a political minefield, Remulla plays his hand like a poker shark in a room full of amateurs. His masterstroke? Letting Garma slink off to Malaysia under an Immigration Lookout Bulletin Order (ILBO), dodging a hold departure order while keeping her domestic charges alive. It’s a move so slick it could slide through a keyhole.

Under Republic Act (RA) No. 6981 (Witness Protection, Security and Benefit Act), Section 9, the DOJ must protect witnesses facing life-threatening risks, especially for crimes under RA 9851 (Philippine Act on Crimes Against International Humanitarian Law), Section 12. Remulla’s decision to let Garma meet ICC officials abroad isn’t cooperation—it’s a calculated sidestep. He fulfills his duty to protect her while upholding the Philippines’ official “no thanks” to the ICC, avoiding any formal breach of the 1987 Constitution, Article II, Section 2 (sovereignty clause). It’s a diplomatic middle finger wrapped in bureaucratic velvet.

His partnership with former Senator Antonio Trillanes IV, Duterte’s political kryptonite, is the icing on this cynical cake. Remulla uses Trillanes as a cutout to funnel Garma to the ICC, sidestepping direct DOJ-ICC contact that could be seen as recognizing the Rome Statute. It’s like hiring a shady courier to deliver a package you don’t want traced. Sure, Trillanes is as popular as a tax hike in Davao, but he’s a necessary evil to manage a toxic asset like Garma. Critics might scream ultra vires, citing the Supreme Court’s Pimentel v. Office of the Executive Secretary (G.R. No. 158988, 2005), but Remulla’s actions fall within his prosecutorial discretion under People v. Lacson (G.R. No. 149453, May 28, 2002). He’s not cooperating; he’s just not not cooperating. Checkmate.

III. The ICC’s Epic Blunder: Betting on a Witness Who’s a Walking Liability

The ICC, in its starry-eyed quest for justice, is betting its Duterte case on a witness who’s less reliable than a rainy-season umbrella. Garma’s testimony is a house of cards, and the ICC’s prosecutors are the ones blowing on it. Article 69(7) of the Rome Statute requires evidence to be credible and probative, but Garma’s laundry list of liabilities—murder charges, a failed asylum bid, and a track record as Duterte’s drug-war enforcer—makes her testimony a defense lawyer’s wet dream. Duterte’s team will feast on this, citing Prosecutor v. Lubanga (ICC-01/04-01/06, 2012), where witness deals were dissected for bias. If Garma’s story unravels, the ICC’s case collapses faster than a shoddy Divisoria stall.

Worse, Garma’s involvement fuels Duterte’s “political persecution” narrative. His allies are already howling about neocolonialism, pointing to the Philippines’ withdrawal from the ICC under Article 127(1) of the Rome Statute as a sovereign mic-drop. The ICC’s “legacy jurisdiction” for 2011–2019 crimes, upheld by the Appeals Chamber in July 2023, may be legally sound, but politically, it’s a lightning rod. Every word from Garma’s mouth hands Duterte’s camp another megaphone to scream “foreign meddling.” The ICC’s obsession with a tainted witness is a self-inflicted wound, bleeding legitimacy faster than you can say “Western double standards.”

IV. Duterte’s Tightrope: A Damned-If-He-Does, Damned-If-He-Doesn’t Predicament

Garma’s testimony, however flimsy, is a poison-tipped arrow aimed at Duterte’s heart. Under Article 28 of the Rome Statute, command responsibility holds superiors liable for subordinates’ crimes if they knew or should have known and failed to act. Garma’s claim that Duterte ordered the “Davao model” nationwide—rewards for killings included—ticks boxes for Article 25(3)(b) (ordering crimes) and Article 7(1)(a) (murder as a crime against humanity). If even one other witness or document backs her up, Duterte’s chances of dodging conviction are slimmer than a Malacañang press release telling the whole truth.

Duterte’s defense leans on discrediting Garma and waving the sovereignty flag. He’ll argue that the Philippines’ withdrawal nullifies ICC jurisdiction, citing Pimentel v. Office of the Executive Secretary (G.R. No. 158988, 2005), which requires domestic laws for treaty enforcement. But the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber (September 15, 2021) already dismissed that, affirming jurisdiction over pre-withdrawal crimes. The Supreme Court’s Secretary of National Defense v. Manalo (G.R. No. 180906, 2008) further weakens his case, emphasizing state accountability for extrajudicial acts. Garma’s testimony, flawed as it is, could be the glue binding victim affidavits to Duterte’s orders, turning his “tough on crime” swagger into a legal guillotine.

V. Sovereignty Sideshow: A Tragicomic Charade Where Everyone’s Faking It

This entire fiasco is a theatrical farce where the ICC brandishes its Rome Statute like a prop sword, the Philippine government plays deaf to The Hague’s overtures, and Remulla sneaks Garma out the back door like a stagehand rigging the lights. It’s sovereignty theatre at its most absurd, with justice as the punchline nobody laughs at. The Philippines’ withdrawal was supposed to be a clean break, yet Remulla’s juggling act—balancing RA 6981 duties with non-cooperation rhetoric—keeps the drama alive.

The stakes? Sky-high. If the Supreme Court’s pending 2025 petition rules Remulla’s actions unconstitutional, it could torch DOJ credibility and ignite Duterte’s base. If Garma’s testimony flops, the ICC’s case implodes, proving Duterte’s “foreign interference” claims. If it holds, the Philippines faces a Sophie’s Choice: cooperate with a court it ditched or double down on sovereignty and risk global pariah status. Meanwhile, the drug war’s victims—6,000 to 30,000 dead—lie forgotten, their graves mere set dressing in this geopolitical melodrama.

VI. Curtain Call: A Circus Where Everyone’s Clowning

Royina Garma is no saint; she’s a self-serving opportunist whose testimony is as reliable as a tabloid headline. The ICC’s gambling its Duterte case on her, risking a spectacular crash-and-burn that could discredit its entire mission. Duterte, for all his bravado, is one corroborated witness away from a legal reckoning that could redefine his legacy as a blood-stained cautionary tale. And Remulla? He’s the only one walking away with a smirk, having outplayed everyone with a legal sleight-of-hand that deserves its own Oscar for cynicism.

This is a high-stakes sideshow where sovereignty, justice, and political survival collide. The ICC’s case hangs by a thread, and Garma’s testimony might just be the scissors. Remulla, meanwhile, is the ringmaster who’s already sold the tickets and slipped out the back. The Philippines watches, popcorn in hand, as the curtain rises on a drama where nobody wins—except maybe the guy who wrote this blog.

Key Citations

- Inquirer.net, “Garma agrees to testify against Duterte before ICC,” September 9, 2025

- Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, Articles 7, 17, 25, 28, 69, 127

- Revised Penal Code, Articles 183, 248

- Republic Act No. 6981 (Witness Protection, Security and Benefit Act)

- Republic Act No. 9851 (Philippine Act on Crimes Against International Humanitarian Law)

- Rules of Court, Rule 132, Section 11

- People of the Philippines v. Sergio Bato and Abraham Bato (G.R. No. 113804, January 16, 1998)

- Pimentel v. Office of the Executive Secretary, G.R. No. 158988, July 2005

- People v. Lacson (G.R. No. 149453, May 28, 2002)

- Secretary of National Defense v. Manalo, G.R. No. 180906, October 2008

- Prosecutor v. Lubanga, ICC-01/04-01/06, 2012

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Just Following Orders” Is Dead: How the Hague Just Turned Tokhang’s Finest Into International Fugitives

Leave a comment