By Louis ‘Barok‘ C. Biraogo — February 15, 2025

IN THE Philippines, where corruption cases outlive the presidents who promise to solve them and where ‘justice’ often takes coffee breaks that last entire administrations, something remarkable just happened: a public official was actually convicted. Sultan Usman Sarangani, a former DENR-ARMM official, didn’t just get a slap on the wrist—he received a jaw-dropping 112-year prison sentence for graft. It should have been a watershed moment, a sign that the system can still hold the powerful accountable. But in a country where impunity is a national pastime, does this conviction mean real change—or is it just another anomaly?

But peel away the layers, and what we see is less a triumph of the rule of law than a case study in its inconsistencies. Sarangani’s fate is sealed, but the larger system that allowed the corruption to flourish remains largely unshaken.

Justice Served, But For Whom?

The Sandiganbayan’s 50-page ruling found Sarangani guilty of 16 counts of violating Section 3(e) of Republic Act No. 3019, the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. His crime? Circumventing public bidding laws by resorting to small-value procurement (or “shopping”) without a valid justification, awarding contracts to companies tied to his co-accused, accountant Nanayaon Dibaratun.

In doing so, Sarangani deprived the government of the transparency and competition required under Republic Act No. 9184, the Government Procurement Reform Act. By funneling public money into favored firms, he violated one of the most basic principles of ethical governance: that public funds should serve the public, not enrich a privileged few.

The case is legally airtight. Section 3(e) of RA 3019 is clear: any public official who, through “manifest partiality, evident bad faith, or gross inexcusable negligence,” causes undue injury to the government or gives unwarranted benefits to a private party is guilty of graft. The Sandiganbayan determined that Sarangani met all three criteria.

And yet, despite the apparent victory, the case raises more questions than it answers.

A Sentence That Means Nothing

Let’s talk about the 112-year prison sentence. Under Article 70 of the Revised Penal Code, the maximum actual time a person can be imprisoned in the Philippines is 40 years. This means that despite the dramatic triple-digit sentence, Sarangani will serve only a fraction of it.

So why the judicial theater? The courts likely wanted to send a message: corruption is a serious crime that carries serious penalties. But does anyone truly believe this will deter other government officials from engaging in graft? History suggests otherwise.

Take the case of Janet Napoles, the mastermind behind the infamous pork barrel scam. Despite her conviction for plundering billions of pesos, corruption scandals continue to emerge year after year. The problem isn’t just the length of sentences; it’s that convictions like Sarangani’s are the exception, not the rule.

If the government truly wanted to deter corruption, it would focus not just on punishing individual actors, but on dismantling the networks of impunity that allow them to operate. That means improving whistleblower protections, strengthening auditing mechanisms, and making it politically costly for those in power to protect the corrupt.

Selective Accountability?

Another glaring inconsistency in this case is Sarangani’s acquittal on 16 counts of violating Section 3(h) of RA 3019, which penalizes public officials with financial interests in transactions they oversee. The court ruled that the Office of the Ombudsman failed to prove beyond reasonable doubt that Sarangani personally profited from the irregular procurement deals.

This raises an uncomfortable reality: while some officials get convicted for irregularities, others escape on technicalities. The prosecution successfully argued that Sarangani engaged in favoritism and abuse of discretion, but it failed to establish that he personally benefited. This means that, under current legal standards, a public official can potentially facilitate corrupt transactions without being directly linked to financial gain and still evade conviction on key charges.

Contrast this with the acquittal of high-profile figures like former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, who walked free despite serious allegations of misuse of public funds. Or consider the recent controversy surrounding Vice President Sara Duterte’s alleged hidden wealth—an issue that, so far, has faced little meaningful legal scrutiny.

Why was Sarangani punished while so many others remain untouched? The answer is as much about politics as it is about law.

When the System Protects Itself

The structural weaknesses of the Philippine justice system are on full display here. Sarangani was a mid-level official, an easy scapegoat. He was not a senator, not a cabinet secretary, not a member of an entrenched political dynasty. He lacked the influence to escape accountability, making him a convenient example to demonstrate that the system still “works.”

Meanwhile, how many high-ranking officials who approved, enabled, or benefited from similar corrupt schemes remain unpunished?

The reality is that corruption in the Philippines is not a matter of a few bad apples—it is systemic. The improper use of small-value procurement methods is widespread, not just in the DENR-ARMM but across various agencies. The Commission on Audit (COA) regularly flags questionable transactions in government reports, yet few result in convictions.

Sarangani’s conviction does nothing to address this broader culture of impunity. If anything, it reinforces the perception that only those without powerful backers are held accountable.

Reforms That Actually Matter

If the government is serious about fighting corruption, it should focus on the following:

- Transparency in Procurement – Implement real-time digital tracking of all government purchases, making contract awards fully accessible to the public.

- Stronger Protections for Whistleblowers – Provide legal and financial incentives for insiders to expose corrupt activities without fear of retaliation.

- Political Consequences for Corrupt Officials – Disqualifications from public office should not just be legal penalties; they should also carry real political weight. Parties that endorse convicted officials should face sanctions.

- Judicial Reforms – The conviction rate for corruption cases remains abysmally low. The Ombudsman and the Sandiganbayan must be given better investigative tools and resources to speed up trials.

- Asset Recovery Mechanisms – The state should aggressively pursue civil forfeiture cases against those convicted of corruption, ensuring that stolen funds are returned to the public.

Conclusion: More Than Just a Headline

Sultan Usman Sarangani’s conviction makes for dramatic news: a government official sentenced to over a century behind bars. But beyond the headline, it is a sobering reminder of how Philippine justice works—and, more importantly, how it doesn’t.

Until corruption is treated not just as a legal violation but as a political and structural crisis, cases like this will remain exceptions rather than signs of real progress. Sarangani will serve his time, but the system that enabled him will remain largely untouched. And until that changes, justice in the Philippines will remain, at best, incomplete.

- ₱75 Million Heist: Cops Gone Full Bandit

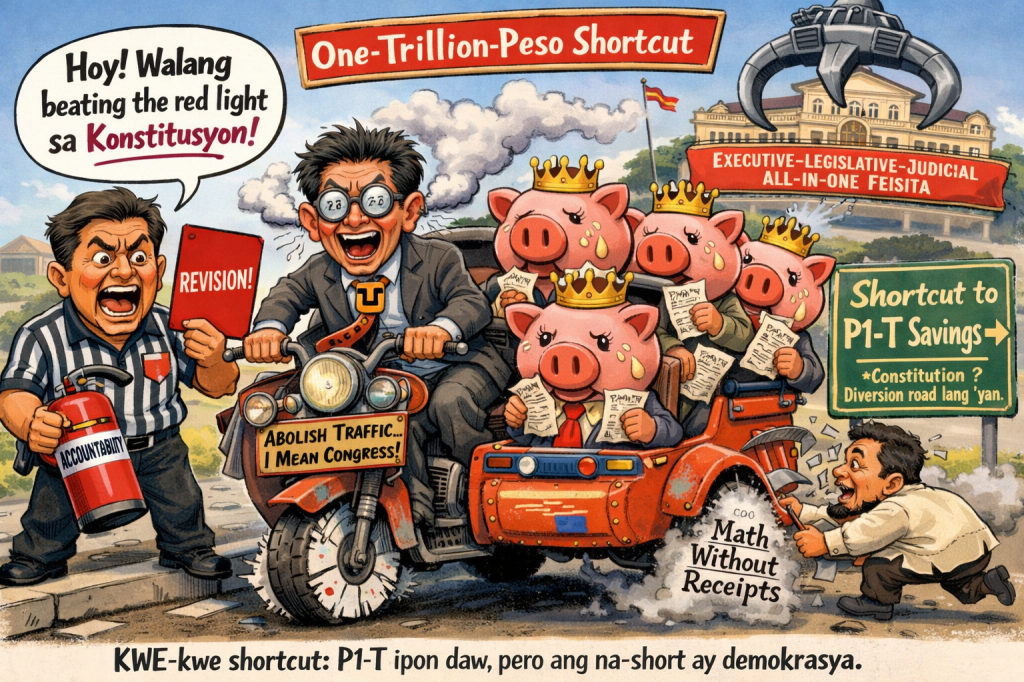

- ₱6.7-Trillion Temptation: The Great Pork Zombie Revival and the “Collegial” Vote-Buying Circus

- ₱1.9 Billion for 382 Units and a Rooftop Pool: Poverty Solved, Next Problem Please

- ₱1.35 Trillion for Education: Bigger Budget, Same Old Thieves’ Banquet

- ₱1 Billion Congressional Seat? Sorry, Sold Out Na Raw — Si Bello Raw Ang Hindi Bumili

- “We Will Take Care of It”: Bersamin’s P52-Billion Love Letter to Corruption

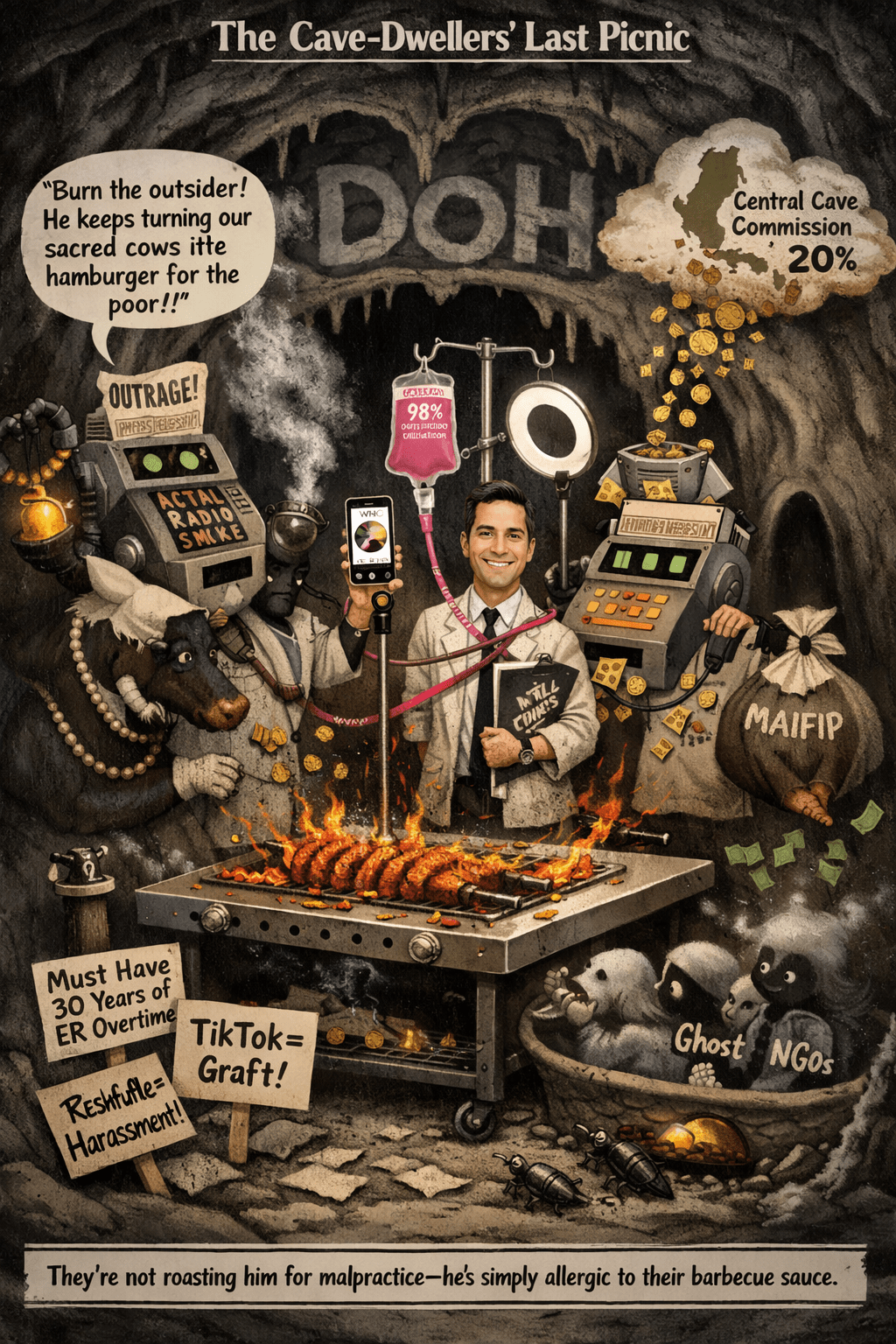

- “Skewed Narrative”? More Like Skewered Taxpayers!

- “Scared to Sign Vouchers” Is Now Official GDP Policy – Welcome to the Philippines’ Permanent Paralysis Economy

- “Robbed by Restitution?” Curlee Discaya’s Tears Over Returning What He Never Earned

- “My Brother the President Is a Junkie”: A Marcos Family Reunion Special

- “Mapipilitan Akong Gawing Zero”: The Day Senator Rodante Marcoleta Confessed to Perjury on National Television and Thought We’d Clap for the Creativity

- “Bend the Law”? Cute. Marcoleta Just Bent the Constitution into a Pretzel

Leave a reply to Louis ‘Barok’ Biraogo Cancel reply